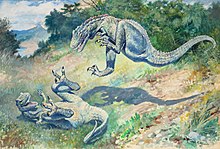

Models recreating a fight between Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex. Epic battles that might have occurred are a popular theme.

A big model of Brachiosaurus in Rishon LeZion's Cinema City, Israel.

Cultural depictions of dinosaurs have been numerous since the word dinosaur

was coined in 1842. The dinosaurs featured in books, films, television

programs, artwork, and other media have been used for both education and

entertainment. The depictions range from the realistic, as in the

television documentaries of the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, or the fantastic, as in the monster movies of the 1950s and 1960s.

The growth in interest in dinosaurs since the Dinosaur Renaissance

has been accompanied by depictions made by artists working with ideas

at the forefront of dinosaur science, presenting lively dinosaurs and feathered dinosaurs

as these concepts were first being considered. Cultural depictions of

dinosaurs have been an important means of translating scientific

discoveries to the public.

Cultural depictions have also created or reinforced

misconceptions about dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, such as

inaccurately and anachronistically portraying a sort of "prehistoric

world" where many kinds of extinct animals (from the Permian animal Dimetrodon to mammoths and cavemen)

lived together, and dinosaurs lived lives of constant combat. Other

misconceptions reinforced by cultural depictions came from a scientific

consensus that has now been overturned, such as dinosaurs being slow and

unintelligent, or the use of dinosaur to describe something that is maladapted or obsolete.

Depictions are necessarily conjectural, because petrification and other fossilization

mechanisms do not preserve all details. Any reconstitution is thereby

an artist's view that, in order to stay within the limits of the best

knowledge at the time, must necessarily be inspired by other pictures

already scientifically proved.

History of depictions

Early human history to 1900: Early depictions

Protoceratops skeleton at the Wyoming Dinosaur Center

The classical folklorist Adrienne Mayor has proposed that the griffin of mythology is based on dinosaur skeletons found in the Gobi Desert. She noted that griffins were said to inhabit the Scythian steppes that reached from modern Ukraine to central Asia. Mayor draws a connection to Protoceratops, a frilled dinosaur commonly found in the Gobi,

sharing features associated with griffins: sharp beaks, four legs,

claws, similar size, large eyes (or eye sockets in the case of the

fossils), and the neck frill of Protoceratops, with large open holes, argued as inspiring descriptions of the griffin's large ears or wings. However, the palaeontologist Mark Witton notes that the suggestion ignores pre-Mycenaean accounts, and has not found favour with archaeologists including N. Wyatt and T.F. Tartaron.

A Megalosaurus statue at Crystal Palace Park in London.

The scientific study of dinosaurs began in 1820s England. In 1842, Richard Owen coined the term dinosaur, which in his vision were elephantine reptiles. An ambitious promoter of his discoveries and theories, Owen was the driving force for the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures,

the first large-scale public dinosaur reconstructions (1854). These

sculptures, which can still be seen today, immortalized a very early

stage in the perception of dinosaurs.

The Crystal Palace sculptures were successful enough that Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Owen's collaborator, sold models of his sculptures and planned a second exhibition, Paleozoic Museum, for Central Park in Manhattan in the late 1860s; it was never completed due to the interference of local politics and "Boss" William Marcy Tweed.

In the same period, dinosaurs first appeared in popular literature, with a passing mention of an Owen-style Megalosaurus in Charles Dickens's Bleak House (1852–1853).

However, depictions of dinosaurs were rare in the 19th century,

possibly due to incomplete knowledge. Despite the well-publicized "Bone Wars" of the late 19th century between the American palaeontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh,

dinosaurs were not yet ingrained in culture. Marsh, although a pioneer

of skeletal reconstructions, did not support putting mounted skeletons

on display, and derided the Crystal Palace sculptures.

1900 to the 1930s: New media

The 1897 painting of "Laelaps" (now Dryptosaurus) by Charles R. Knight.

As study caught up to the wealth of new material from western North

America, and venues for depictions proliferated, dinosaurs gained in

popularity. The paintings of Charles R. Knight were the first influential representations of these finds. Knight worked extensively with the American Museum of Natural History and its director, Henry Fairfield Osborn, who wanted to use dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals to promote his museum and his ideas on evolution.

Knight's work, found in museums around the United States, helped popularize dinosaurs and influenced generations of paleoartists. His early work showing fighting "Laelaps" (=Dryptosaurus) depicted dinosaurs as much more lively than they would be presented for much of the 20th century.

At the same time, improvements in casting allowed dinosaur skeletons to

be reproduced and shipped across the world for display in far-flung

museums, bringing them to the attention of a wider audience; Diplodocus was the first such dinosaur reproduced in this way.

Dinosaurs began appearing in films soon after the introduction of cinema, the first being the good-natured animated Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914. However, lovable dinosaurs were quickly replaced as moviemakers recognized the thrill of huge frightening monsters. D. W. Griffith in 1914's Brute Force provided the first example of a threatening cinematic dinosaur, a Ceratosaurus

who menaced cavemen. This film enshrined the fiction that dinosaurs and

early humans lived together, and set up the cliché that dinosaurs were

bloodthirsty and attacked anything that moved.

The now-common trope of dinosaurs extant in isolated locations in today's world appeared at the same time, beginning with Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World (1912) and the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs. The Lost World crossed into the movies in 1925, setting heights for special effects

and attempts at scientific accuracy. It is unusual, even today, for

attempting to portray dinosaurs as something other than monsters in

constant combat.

The stop-motion techniques of Willis O'Brien went on to bring dinosaurs to life in the 1933 film King Kong, which merged the tropes of dinosaur combat and dinosaurs in a lost world. His protégé Ray Harryhausen would continue to refine this method, but most later dinosaurs movies until the advent of CGI

would eschew such expensive effects for cheaper methods, such as humans

in dinosaur suits and modern reptiles with dinosaur decorations,

enlarged by cinematography. Dinosaur depictions diversified in the 1930s, spreading to newspaper comic strips in Alley Oop and to advertising for Sinclair Oil.

The 1930s to 1970s: Moribund dinosaurs to renaissance

Scene from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953).

The Great Depression and World War II combined to sink the study of dinosaurs into a decades-long lull. Scientists considered dinosaurs a group of unrelated animals that left no descendants, and dinosaurs were presented as stupid, slow, stuck in swamps, and doomed to extinction. Scientific dinosaur artwork, primarily from Rudolph F. Zallinger and Zdeněk Burian,

reflected and reinforced the conception of dinosaurs as slow and static

(one artistic quirk that became commonplace in representations of Mesozoic landscapes, the presence of a volcano, was a hallmark of Zallinger's). From such ideas came the alternate use of "dinosaur" as something out of date.

Films of the time typically used dinosaurs as monsters, with the added element of atomic fears in the early Cold War. Thus, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and Godzilla (1954; American release 1956) portray monstrous dinosaur-like prehistoric reptiles that go on rampages after being awakened by atomic bomb tests. An alternative appears in Disney's animated Fantasia (1940), in its The Rite of Spring

sequence, which attempted to portray dinosaurs with some scientific

accuracy (although it has the common error of showing prehistoric

animals from many different time periods living at the same time) and also in Karel Zeman's Cesta do praveku (1955; Journey to the Beginning of Time), a Czechoslovakian children's science fiction movie inspired by Zdeněk Burian's work.

Feathered restoration of Deinonychus antirrhopus.

In 1956, Oliver Butterworth authored a children's book, The Enormous Egg. The book and a movie adaptation televised in 1968 by the NBC Children's Theatre tell the story of a boy who finds an enormous egg laid by a hen that hatches a baby Triceratops. The dinosaur, named Uncle Beazley, becomes too big, so the boy brings him to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Beazley is first kept at the National Museum of Natural History, but is eventually transferred to the National Zoo's Elephant House because there is a law against stabling large animals in the District of Columbia.

Dinosaurs gained a home in television in the 1960s animated sitcom The Flintstones, in another example of dinosaurs shown as coexisting with humans (for comedic effect in this case). Dinosaurs also entered comic books in this period in such series as Tor and Turok, Son of Stone,

where prehistoric humans fought anachronistic dinosaurs. For those

wanting more scientific accounts of dinosaurs, there were the first

nontechnical dinosaur books. Ned Colbert's The Dinosaur Book

(1945) was the first such book, and its status as the only such book

for many years made Colbert an important figure for the coming

generations of paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts.

In the 1960s, paleontologist John Ostrom began work on the theropod Deinonychus. His findings, which were expanded upon by his student Robert T. Bakker, contributed to the Dinosaur Renaissance, a revolution in the study of dinosaurs. Of particular importance were a reevaluation of the origin of birds that showed them to be closely related to coelurosaurian dinosaurs, reappraisal of dinosaur physiology that suggested they weren't the sluggish cold-blooded animals they'd long been assumed to be, and a recognition that dinosaurs formed a natural group.

Soon thereafter came new evidence on dinosaur social behavior, with nests of Maiasaura suggesting parental care. These findings were reflected in the work of a new generation of paleoartists. One milestone was Sarah Landry's feathered dinosaur in Bakker's 1975 Scientific American article, Dinosaur Renaissance.

Louis Paul Jonas created the first full sized dinosaur sculptures for the 1964 New York World's Fair in the "Dinoland" area, which was sponsored by the Sinclair Oil Corporation, whose logo featured a dinosaur. Jonas consulted with paleontologists Barnum Brown, Edwin H. Colbert

and John Ostrom in order to create nine sculptures that were as

accurate as possible. After the Fair closed, the dinosaur models toured

the country on flatbed trailers as part of a company advertising

campaign. Most of the statues are now on display at various museums and

parks.

Uncle Beazley sculpture on the National Mall in front of the National Museum of Natural History between 1980 and 1994

Uncle Beazley at the National Zoo in February 2012 after repainting

In 1967, the Sinclair Oil Corporation gave one of its dinosaurs, a fiberglass model of a Triceratops, to the Smithsonian Institution. The model, which appeared in The Enormous Egg television movie in 1968 as Uncle Beazley, is now on display at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. From the 1970s to 1994, the statue was located on the National Mall in front of the National Museum of Natural History. (Some sources state that the Kentucky Science Center in Louisville (formerly named the "Louisville Museum of Natural History and Science" and the "Louisville Science Center") now owns the Triceratops model).

The 1980s to the present: Dinosaurs reconsidered

Outdated and modern reconstructions of Iguanodon.

The reevaluation of dinosaurs spurred public interest, with the new

generation of paleoartists quick to respond. Artists such as Mark Hallett, Doug Henderson, John Gurche, Gregory S. Paul, William Stout, and Bob Walters illustrated the new findings in response to the demand.

By the latter half of the 1980s and into the 1990s, other media

were showing the influence of the increased popularity, with diverse

depictions aimed at a variety of ages and interests.

In 1990 the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural

History in Washington, D.C., featured an exhibition of dinosaur

sculpture by Jim Gary that drew more visitors than any of its previous exhibits. His Twentieth Century Dinosaurs, popular since the 1960s, began being featured in textbooks, encyclopedias, and videos as well as later, by the likes of National Geographic, in their publications for children in 1975.

For preschoolers, there was the educational television show Barney & Friends starting in 1992; their older siblings had the 1988 animated movie The Land Before Time and its increasing line of direct to video sequels (13 by 2016). Dinosaurs, a television sitcom, parodied humans and other television shows. Of particular note is Michael Crichton's 1990 novel, Jurassic Park, the popularity of which led to a series of films and other media. The first of these, Jurassic Park, married advanced CGI with advances in scientific knowledge of dinosaurs. The Disney film, Dinosaur

was the most expensive movie in 2000, but was a box-office success. The

falling cost of computer-generated effects also has recently allowed

the increased production of documentaries for television; the

award-winning 1999 BBC series Walking with Dinosaurs, the 2001 When Dinosaurs Roamed America, the 2003 Dinosaur Planet, the 2009 Animal Armageddon, and the 2011 Planet Dinosaur are notable examples.

In April 2016, a proposal was submitted to the Unicode committee to encode three pictures of heads of three dinosaur species considered exemplary as emoji.

Public perception of dinosaurs

Sculpture of tyrannosaurid and sheep (10 meters long and 4 meters tall) as anticlerical propaganda

The popular ideals of dinosaurs have many misconceptions, reinforced by films, books, comics, television shows, and even theme parks. Typical errors include: prehistoric humans living with dinosaurs; dinosaurs as monsters that did little else but fight; the portrayal of a kind of "prehistoric world" where all prehistoric animals are shown to exist; dinosaurs as all large; dinosaurs as stupid and slow-moving; dinosaurs as being lizard-like and all scaled (non-feathered) when many theropod dinosaurs such as Velociraptor had feathers, and the inclusion of many prehistoric animals (such as Dimetrodon, ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, pterosaurs, and plesiosaurs) as dinosaurs;

Moreover, dinosaurs did not become extinct due to being generally

maladapted or unable to cope with normal climatic change, a view found

in many older textbooks.

Reports in the news media of dinosaur finds and dinosaur science

are often inaccurate and sensationalistic, and popular dinosaur books

usually lag scientific understanding. Dinosaur toys and models are often inaccurate, packaged indiscriminately with other prehistoric animals, or have fictitious additions like the large sharp teeth in some rubber Triceratops toys.

The pejorative use of "dinosaur" as something behind the times

has been applied to people, styles, and ideas that are perceived to be

out of date, and on the wane. For example, members of the punk movement derided the "progressive" bands that preceded them as "dinosaur bands".

However, some popular depictors have striven for accuracy and presented up-to-date information; Michael Crichton and Bill Watterson (of Calvin and Hobbes)

are two recent examples. Paleoartists and illustrators in particular

have kept up with research. Popular conceptions of dinosaurs have also

been important in stimulating the interest and imagination of young

people, and have been responsible for introducing many who would later

become paleontologists to the field. In addition, popular depictions

have the freedom to be more imaginative and speculative than technical

works.

Usage

The typical use of dinosaurs in popular culture has been as vicious monsters. There are several distinct genres of dinosaur depictions commonly used: "lost worlds" on modern Earth; time travel stories; educational works for children; prehistoric world stories (often with cavemen); and dinosaurs running amok in the modern world.

Appeal

The appeal of dinosaurs, as suggested by author, researcher, and dinosaur enthusiast Donald F. Glut,

has multiple factors. Dinosaurs were "monsters," yet are safely

extinct, allowing for vicarious thrills. They appeal to the imagination,

and there are many ways to approach them intellectually. Finally, they

appeal to adults nostalgic for what they enjoyed as children. Children

have been particularly drawn to dinosaurs over the years.