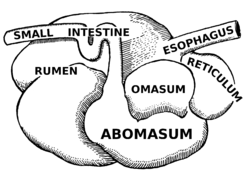

Stylised illustration of a ruminant digestive system

Ruminants are mammals that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach

prior to digestion, principally through microbial actions. The process,

which takes place in the front part of the digestive system and

therefore is called foregut fermentation, typically requires the fermented ingesta (known as cud)

to be regurgitated and chewed again. The process of rechewing the cud

to further break down plant matter and stimulate digestion is called rumination. The word "ruminant" comes from the Latin ruminare, which means "to chew over again".

The roughly 200 species of living ruminants include both domestic and wild species. Ruminating mammals include cattle, all domesticated and wild bovines, goats, sheep, giraffes, deer, gazelles, and antelopes. It has also been suggested that notoungulates also relied on rumination, as opposed to other atlantogenates that rely on the more typical hindgut fermentation, though this is not entirely certain.

Taxonomically, the suborder Ruminantia (also known as ruminants) is a lineage of herbivorous artiodactyls that includes the most advanced and widespread of the world's ungulates. The term 'ruminant' is not synonymous with Ruminantia. The suborder Ruminantia includes many ruminant species, but does not include tylopods and marsupials. The suborder Ruminantia includes six different families: Tragulidae, Giraffidae, Antilocapridae, Moschidae, Cervidae, and Bovidae.

Description

Different forms of the stomach in mammals. A, dog; B, Mus decumanus; C, Mus musculus; D, weasel; E, scheme of the ruminant stomach, the arrow with the dotted line showing the course taken by the food; F, human stomach. a, minor curvature; b, major curvature; c, cardiac end G, camel; H, Echidna aculeata. Cma, major curvature; Cmi, minor curvature. I, Bradypus tridactylus

Du, duodenum; MB, coecal diverticulum; **, outgrowths of duodenum; †,

reticulum; ††, rumen. A (in E and G), abomasum; Ca, cardiac division; O,

psalterium; Oe, oesophagus; P, pylorus; R (to the right in E and to the

left in G), rumen; R (to the left in E and to the right in G),

reticulum; Sc, cardiac division; Sp, pyloric division; WZ, water-cells.

(from Wiedersheim's Comparative Anatomy)

Food digestion in the simple stomach of nonruminant animals versus ruminants

The primary difference between ruminants and nonruminants is that ruminants' stomachs have four compartments:

- rumen—primary site of microbial fermentation

- reticulum

- omasum—receives chewed cud, and absorbs volatile fatty acids

- abomasum—true stomach

The first two chambers are the rumen and the reticulum. These two

compartments make up the fermentation vat, they are the major site of

microbial activity. Fermentation is crucial to digestion because it

breaks down complex carbohydrates, such as cellulose, and enables the

animal to utilize them. Microbes function best in a warm, moist,

anaerobic environment with a temperature range of 37.7 to 42.2 °C (100

to 108 °F) and a pH between 6.0 and 6.4. Without the help of microbes,

ruminants would not be able to utilize nutrients from forages. The food is mixed with saliva and separates into layers of solid and liquid material. Solids clump together to form the cud or bolus.

The cud is then regurgitated and chewed to completely mix it with

saliva and to break down the particle size. Smaller particle size

allows for increased nutrient absorption. Fiber, especially cellulose and hemicellulose, is primarily broken down in these chambers by microbes (mostly bacteria, as well as some protozoa, fungi, and yeast) into the three volatile fatty acids (VFAs): acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid. Protein and nonstructural carbohydrate (pectin, sugars, and starches)

are also fermented. Saliva is very important because it provides liquid

for the microbial population, recirculates nitrogen and minerals, and

acts as a buffer for the rumen pH. The type of feed the animal consumes affects the amount of saliva that is produced.

Though the rumen and reticulum have different names, they have

very similar tissue layers and textures, making it difficult to visually

separate them. They also perform similar tasks. Together, these

chambers are called the reticulorumen. The degraded digesta, which is

now in the lower liquid part of the reticulorumen, then passes into the

next chamber, the omasum. This chamber controls what is able to pass

into the abomasum. It keeps the particle size as small as possible in

order to pass into the abomasum. The omasum also absorbs volatile fatty

acids and ammonia.

After this, the digesta is moved to the true stomach, the

abomasum. This is the gastric compartment of the ruminant stomach. The

abomasum is the direct equivalent of the monogastric

stomach, and digesta is digested here in much the same way. This

compartment releases acids and enzymes that further digest the material

passing through. This is also where the ruminant digests the microbes

produced in the rumen. Digesta is finally moved into the small intestine,

where the digestion and absorption of nutrients occurs. The small

intestine is the main site of nutrient absorption. The surface area of

the digesta is greatly increased here because of the villi that are in

the small intestine. This increased surface area allows for greater

nutrient absorption. Microbes produced in the reticulorumen are also

digested in the small intestine. After the small intestine is the large

intestine. The major roles here are breaking down mainly fiber by

fermentation with microbes, absorption of water (ions and minerals) and

other fermented products, and also expelling waste. Fermentation continues in the large intestine in the same way as in the reticulorumen.

Only small amounts of glucose

are absorbed from dietary carbohydrates. Most dietary carbohydrates are

fermented into VFAs in the rumen. The glucose needed as energy for the

brain and for lactose

and milk fat in milk production, as well as other uses, comes from

nonsugar sources, such as the VFA propionate, glycerol, lactate, and

protein. The VFA propionate is used for around 70% of the glucose and glycogen produced and protein for another 20% (50% under starvation conditions).

Classification and taxonomy

Hofmann

and Stewart divided ruminants into three major categories based on

their feed type and feeding habits: concentrate selectors, intermediate

types, and grass/roughage eaters, with the assumption that feeding

habits in ruminants cause morphological differences in their digestive

systems, including salivary glands, rumen size, and rumen papillae.

However, Woodall found that there is little correlation between the

fiber content of a ruminant's diet and morphological characteristics,

meaning that the categorical divisions of ruminants by Hofmann and

Stewart warrant further research.

Also, some mammals are pseudoruminants, which have a three-compartment stomach instead of four like ruminants. The Hippopotamidae (comprising hippopotami) are well-known examples. Pseudoruminants, like traditional ruminants, are foregut fermentors and most ruminate or chew cud. However, their anatomy and method of digestion differs significantly from that of a four-chambered ruminant.

Monogastric herbivores, such as rhinoceroses, horses, and rabbits, are not ruminants, as they have a simple single-chambered stomach. These hindgut fermenters digest cellulose in an enlarged cecum through the reingestion of the cecotrope.

Abundance, distribution, and domestication

Wild ruminants number at least 75 million and are native to all continents except Antarctica.

Nearly 90% of all species are found in Eurasia and Africa. Species

inhabit a wide range of climates (from tropic to arctic) and habitats

(from open plains to forests).

The population of domestic ruminants is greater than 3.5 billion,

with cattle, sheep, and goats accounting for about 95% of the total

population. Goats were domesticated in the Near East circa 8000 BC. Most other species were domesticated by 2500 BC., either in the Near East or southern Asia.

Ruminant physiology

Ruminating

animals have various physiological features that enable them to survive

in nature. One feature of ruminants is their continuously growing

teeth. During grazing, the silica content in forage

causes abrasion of the teeth. This abrasion is compensated for by

continuous tooth growth throughout the ruminant's life, as opposed to

humans or other nonruminants, whose teeth stop growing after a

particular age. Most ruminants do not have upper incisors; instead, they

have a thick dental pad to thoroughly chew plant-based food.

Another feature of ruminants is the large ruminal storage capacity that

gives them the ability to consume feed rapidly and complete the chewing

process later. This is known as rumination, which consists of the

regurgitation of feed, rechewing, resalivation, and reswallowing.

Rumination reduces particle size, which enhances microbial function and

allows the digesta to pass more easily through the digestive tract.

Rumen microbiology

Vertebrates lack the ability to hydrolyse the beta [1–4] glycosidic bond of plant cellulose due to the lack of the enzyme cellulase.

Thus, ruminants must completely depend on the microbial flora, present

in the rumen or hindgut, to digest cellulose. Digestion of food in the

rumen is primarily carried out by the rumen microflora, which contains

dense populations of several species of bacteria, protozoa, sometimes yeasts and other fungi – 1 ml of rumen is estimated to contain 10–50 billion bacteria and 1 million protozoa, as well as several yeasts and fungi.

Since the environment inside a rumen is anaerobic, most of these microbial species are obligate or facultative anaerobes that can decompose complex plant material, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, and proteins.

The hydrolysis of cellulose results in sugars, which are further

fermented to acetate, lactate, propionate, butyrate, carbon dioxide, and

methane.

As bacteria conduct fermentation in the rumen, they consume about

10% of the carbon, 60% of the phosphorus, and 80% of the nitrogen that

the ruminant ingests. To reclaim these nutrients, the ruminant then digests the bacteria in the abomasum. The enzyme lysozyme has adapted to facilitate digestion of bacteria in the ruminant abomasum. Pancreatic ribonuclease also degrades bacterial RNA in the ruminant small intestine as a source of nitrogen.

During grazing, ruminants produce large amounts of saliva – estimates range from 100 to 150 litres of saliva per day for a cow. The role of saliva is to provide ample fluid for rumen fermentation and to act as a buffering agent.

Rumen fermentation produces large amounts of organic acids, thus

maintaining the appropriate pH of rumen fluids is a critical factor in

rumen fermentation. After digesta pass through the rumen, the omasum

absorbs excess fluid so that digestive enzymes and acid in the abomasum

are not diluted.

Tannin toxicity in ruminant animals

Tannins are phenolic compounds

that are commonly found in plants. Found in the leaf, bud, seed, root,

and stem tissues, tannins are widely distributed in many different

species of plants. Tannins are separated into two classes: hydrolysable

tannins and condensed tannins.

Depending on their concentration and nature, either class can have

adverse or beneficial effects. Tannins can be beneficial, having been

shown to increase milk production, wool growth, ovulation rate, and

lambing percentage, as well as reducing bloat risk and reducing internal

parasite burdens.

Tannins can be toxic to ruminants, in that they precipitate

proteins, making them unavailable for digestion, and they inhibit the

absorption of nutrients by reducing the populations of proteolytic rumen

bacteria. Very high levels of tannin intake can produce toxicity that can even cause death.

Animals that normally consume tannin-rich plants can develop defensive

mechanisms against tannins, such as the strategic deployment of lipids and extracellular polysaccharides that have a high affinity to binding to tannins.

Some ruminants (goats, deer, elk, moose) are able to consume feed high

in tannins (leaves, twigs, bark) due to the presence in their saliva of

tannin-binding proteins.

Religious importance

The Law of Moses in the Bible only allowed the eating of mammals that had cloven hooves (i.e. members of the order Artiodactyla) and "that chew the cud", a stipulation preserved to this day in Jewish dietary laws.

Other uses

The verb 'to ruminate' has been extended metaphorically to mean to ponder thoughtfully or to meditate

on some topic. Similarly, ideas may be 'chewed on' or 'digested'. 'Chew

the (one's) cud' is to reflect or meditate. In psychology, "rumination" refers to a pattern of thinking, and is unrelated to digestive physiology.

Ruminants and climate change

Methane is produced by a type of archaea, called methanogens,

as described above within the rumen, and this methane is released to

the atmosphere. The rumen is the major site of methane production in

ruminants. Methane is a strong greenhouse gas with a global warming potential of 86 compared to CO2 over a 20-year period.

In 2010, enteric fermentation accounted for 43% of the total greenhouse gas emissions from all agricultural activity in the world, 26% of the total greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural activity in the U.S., and 22% of the total U.S. methane emissions.

The meat from domestically-raised ruminants has a higher carbon

equivalent footprint than other meats or vegetarian sources of protein

based on a global meta-analysis of lifecycle assessment studies.

Methane production by meat animals, principally ruminants, is estimated

15–20% global production of methane, unless the animals were hunted in

the wild.

However, the current U.S. domestic beef and dairy cattle population is

around 90 million head, which is not much different from the peak wild

population of American Bison that primarily roamed the part of North

America that now makes up the U.S. This is estimated to have been over

60 million head in the 1700s and prior.

In addition, EPA estimates suggest bison produce more methane per head

than cattle, with modern feedlot beef cattle producing perhaps as low as

half the methane of bison per head. Therefore, it is likely that the

pre-industrialized North American wild bison herd released more total

methane into the atmosphere than the current total domesticated herd of

beef and dairy cattle.