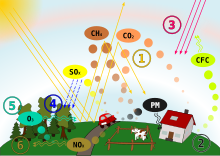

Processes involved in acid deposition (only SO2 and NOx play a significant role in acid rain).

Acid clouds can grow on SO2 emissions from refineries, as seen here in Curaçao.

Acid rain is a rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). It can have harmful effects on plants, aquatic animals and infrastructure. Acid rain is caused by emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide, which react with the water molecules in the atmosphere

to produce acids. Some governments have made efforts since the 1970s to

reduce the release of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide into the

atmosphere with positive results. Nitrogen oxides can also be produced

naturally by lightning strikes, and sulfur dioxide is produced by volcanic eruptions.

Acid rain has been shown to have adverse impacts on forests,

freshwaters and soils, killing insect and aquatic life-forms, causing

paint to peel, corrosion of steel structures such as bridges, and weathering of stone buildings and statues as well as having impacts on human health.

Definition

"Acid rain" is a popular term referring to the deposition of a

mixture from wet (rain, snow, sleet, fog, cloudwater, and dew) and dry

(acidifying particles and gases) acidic components. Distilled water, once carbon dioxide is removed, has a neutral pH of 7. Liquids with a pH less than 7 are acidic, and those with a pH

greater than 7 are alkaline. "Clean" or unpolluted rain has an acidic

pH, but usually no lower than 5.7, because carbon dioxide and water in

the air react together to form carbonic acid, a weak acid according to the following reaction:

Unpolluted rain can also contain other chemicals which affect its pH (acidity level). A common example is nitric acid produced by electric discharge in the atmosphere such as lightning. Acid deposition as an environmental issue (discussed later in the article) would include additional acids other than H2CO3.

History

The corrosive effect of polluted, acidic city air on limestone and marble was noted in the 17th century by John Evelyn, who remarked upon the poor condition of the Arundel marbles.

Since the Industrial Revolution, emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere have increased. In 1852, Robert Angus Smith was the first to show the relationship between acid rain and atmospheric pollution in Manchester, England.

In the late 1960s scientists began widely observing and studying the phenomenon. The term "acid rain" was coined in 1872 by Robert Angus Smith.

Canadian Harold Harvey was among the first to research a "dead" lake.

At first the main focus in research lay on local effects of acid rain. Waldemar Christofer Brøgger was the first to acknowledge long-distance transportation of pollutants crossing borders from the United Kingdom to Norway. Public awareness of acid rain in the US increased in the 1970s after The New York Times published reports from the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire of the harmful environmental effects that result from it.

Occasional pH readings in rain and fog water of well below 2.4 have been reported in industrialized areas. Industrial acid rain is a substantial problem in China and Russia and areas downwind from them. These areas all burn sulfur-containing coal to generate heat and electricity.

The problem of acid rain has not only increased with population

and industrial growth, but has become more widespread. The use of tall

smokestacks to reduce local pollution has contributed to the spread of acid rain by releasing gases into regional atmospheric circulation.

Often deposition occurs a considerable distance downwind of the

emissions, with mountainous regions tending to receive the greatest

deposition (because of their higher rainfall). An example of this effect

is the low pH of rain which falls in Scandinavia.

In the United States

Since 1998, Harvard University wraps some of the bronze and marble statues on its campus, such as this "Chinese stele", with waterproof covers every winter, in order to protect them from corrosion caused by acid rain and acid snow

The earliest report about acid rain in the United States was from the chemical evidence from Hubbard Brook Valley. In 1972, a group of scientists including Gene Likens discovered the rain that was deposited at White Mountains of New Hampshire was acidic. The pH of the sample was measured to be 4.03 at Hubbard Brook.

The Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study followed up with a series of research

that analyzed the environmental effects of acid rain. Acid rain that

mixed with stream water at Hubbard Brook was neutralized by the alumina

from soils.

The result of this research indicates the chemical reaction between

acid rain and aluminum leads to increasing rate of soil weathering.

Experimental research was done to examine the effects of increased

acidity in stream on ecological species. In 1980, a group of scientists

modified the acidity of Norris Brook, New Hampshire, and observed the

change in species' behaviors. There was a decrease in species diversity,

an increase in community dominants, and a decrease in the food web complexity.

In 1980, the US Congress passed an Acid Deposition Act.

This Act established an 18-year assessment and research program under

the direction of the National Acidic Precipitation Assessment Program

(NAPAP). NAPAP looked at the entire problem from a scientific

perspective. It enlarged a network of monitoring sites to determine how

acidic the precipitation actually was, and to determine long-term

trends, and established a network for dry deposition. It looked at the

effects of acid rain and funded research on the effects of acid

precipitation on freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems, historical

buildings, monuments, and building materials. It also funded extensive

studies on atmospheric processes and potential control programs.

From the start, policy advocates from all sides attempted to

influence NAPAP activities to support their particular policy advocacy

efforts, or to disparage those of their opponents.

For the US Government's scientific enterprise, a significant impact of

NAPAP were lessons learned in the assessment process and in

environmental research management to a relatively large group of

scientists, program managers and the public.

In 1981, the National Academy of Sciences was looking into research about the controversial issues regarding acid rain. President Ronald Reagan did not place a huge attention on the issues of acid rain

until his personal visit to Canada and confirmed that Canadian border

suffered from the drifting pollution from smokestacks in Midwest of US.

Reagan honored the agreement to Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s enforcement of anti-pollution regulation. In 1982, US President Ronald Reagan commissioned William Nierenberg to serve on the National Science Board. Nierenberg selected scientists including Gene Likens

to serve on a panel to draft a report on acid rain. In 1983, the panel

of scientists came up with a draft report, which concluded that acid

rain is a real problem and solutions should be sought. White House Office of Science and Technology Policy reviewed the draft report and sent Fred Singer’s suggestions of the report, which cast doubt on the cause of acid rain.

The panelists revealed rejections against Singer’s positions and

submitted the report to Nierenberg in April. In May 1983, the House of

Representatives voted against legislation that aimed to control sulfur

emissions. There was a debate about whether Nierenberg delayed to

release the report. Nierenberg himself denied the saying about his

suppression of the report and explained that the withheld of the report

after the House's vote was due to the fact that the report was not ready

to be published.

In 1991, the US National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program (NAPAP) provided its first assessment of acid rain in the United States.

It reported that 5% of New England Lakes were acidic, with sulfates

being the most common problem. They noted that 2% of the lakes could no

longer support Brook Trout, and 6% of the lakes were unsuitable for the survival of many species of minnow. Subsequent Reports to Congress

have documented chemical changes in soil and freshwater ecosystems,

nitrogen saturation, decreases in amounts of nutrients in soil, episodic

acidification, regional haze, and damage to historical monuments.

Meanwhile, in 1990, the US Congress passed a series of amendments to the Clean Air Act. Title IV of these amendments established the a cap and trade system designed to control emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. Title IV called for a total reduction of about 10 million tons of SO2 emissions from power plants, close to a 50% reduction.

It was implemented in two phases. Phase I began in 1995, and limited

sulfur dioxide emissions from 110 of the largest power plants to a

combined total of 8.7 million tons of sulfur dioxide. One power plant in

New England (Merrimack) was in Phase I. Four other plants (Newington,

Mount Tom, Brayton Point, and Salem Harbor) were added under other

provisions of the program. Phase II began in 2000, and affects most of

the power plants in the country.

During the 1990s, research continued. On March 10, 2005, the EPA

issued the Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR). This rule provides states

with a solution to the problem of power plant pollution that drifts from

one state to another. CAIR will permanently cap emissions of SO2 and NOx in the eastern United States. When fully implemented, CAIR will reduce SO2 emissions in 28 eastern states and the District of Columbia by over 70% and NOx emissions by over 60% from 2003 levels.

Overall, the program's cap and trade program has been successful in achieving its goals. Since the 1990s, SO2 emissions have dropped 40%, and according to the Pacific Research Institute, acid rain levels have dropped 65% since 1976. Conventional regulation was used in the European Union, which saw a decrease of over 70% in SO2 emissions during the same time period.

In 2007, total SO2 emissions were 8.9 million tons, achieving the program's long-term goal ahead of the 2010 statutory deadline.

In 2007 the EPA estimated that by 2010, the overall costs of

complying with the program for businesses and consumers would be $1

billion to $2 billion a year, only one fourth of what was originally

predicted. Forbes says: In

2010, by which time the cap and trade system had been augmented by the

George W. Bush administration's Clean Air Interstate Rule, SO2 emissions

had fallen to 5.1 million tons.

The term citizen science can be traced back as far as January 1989 and a campaign by the Audubon Society to measure acid rain. Scientist Muki Haklay cites in a policy report for the Wilson Center

entitled 'Citizen Science and Policy: A European Perspective' a first

use of the term 'citizen science' by R. Kerson in the magazine MIT Technology Review from January 1989.

Quoting from the Wilson Center report: "The new form of engagement in

science received the name "citizen science". The first recorded example

of the use of the term is from 1989, describing how 225 volunteers

across the US collected rain samples to assist the Audubon Society in an

acid-rain awareness raising campaign. The volunteers collected samples,

checked for acidity, and reported back to the organization. The

information was then used to demonstrate the full extent of the

phenomenon."

Emissions of chemicals leading to acidification

The most important gas which leads to acidification is sulfur dioxide. Emissions of nitrogen oxides which are oxidized to form nitric acid are of increasing importance due to stricter controls on emissions of sulfur compounds. 70 Tg(S) per year in the form of SO2 comes from fossil fuel combustion and industry, 2.8 Tg(S) from wildfires and 7–8 Tg(S) per year from volcanoes.

Natural phenomena

The principal natural phenomena that contribute acid-producing gases to the atmosphere are emissions from volcanoes. Thus, for example, fumaroles from the Laguna Caliente crater of Poás Volcano

create extremely high amounts of acid rain and fog, with acidity as

high as a pH of 2, clearing an area of any vegetation and frequently

causing irritation to the eyes and lungs of inhabitants in nearby

settlements. Acid-producing gasses are also created by biological processes that occur on the land, in wetlands, and in the oceans. The major biological source of sulfur compounds is dimethyl sulfide.

Nitric acid in rainwater is an important source of fixed nitrogen for plant life, and is also produced by electrical activity in the atmosphere such as lightning.

Acidic deposits have been detected in glacial ice thousands of years old in remote parts of the globe.

Soils of coniferous forests

are naturally very acidic due to the shedding of needles, and the

results of this phenomenon should not be confused with acid rain.

Human activity

The coal-fired Gavin Power Plant in Cheshire, Ohio

The principal cause of acid rain is sulfur and nitrogen compounds from human sources, such as electricity generation, factories, and motor vehicles.

Electrical power generation using coal is among the greatest

contributors to gaseous pollution responsible for acidic rain. The gases

can be carried hundreds of kilometers in the atmosphere before they are

converted to acids and deposited. In the past, factories had short

funnels to let out smoke but this caused many problems locally; thus,

factories now have taller smoke funnels. However, dispersal from these

taller stacks causes pollutants to be carried farther, causing

widespread ecological damage.

Chemical processes

Combustion of fuels produces sulfur dioxide and nitric oxides. They are converted into sulfuric acid and nitric acid.

Gas phase chemistry

In the gas phase sulfur dioxide is oxidized by reaction with the hydroxyl radical via an intermolecular reaction:

- SO2 + OH· → HOSO2·

which is followed by:

- HOSO2· + O2 → HO2· + SO3

In the presence of water, sulfur trioxide (SO3) is converted rapidly to sulfuric acid:

- SO3 (g) + H2O (l) → H2SO4 (aq)

Nitrogen dioxide reacts with OH to form nitric acid:

This shows the process of the air pollution being released into the atmosphere and the areas that will be affected.

- NO2 + OH· → HNO3

Chemistry in cloud droplets

When clouds are present, the loss rate of SO2 is faster than can be explained by gas phase chemistry alone. This is due to reactions in the liquid water droplets.

- Hydrolysis

Sulfur dioxide dissolves in water and then, like carbon dioxide, hydrolyses in a series of equilibrium reactions:

- SO2 (g) + H2O ⇌ SO2·H2O

- SO2·H2O ⇌ H+ + HSO3−

- HSO3− ⇌ H+ + SO32−

- Oxidation

There are a large number of aqueous reactions that oxidize sulfur from S(IV) to S(VI), leading to the formation of sulfuric acid. The most important oxidation reactions are with ozone, hydrogen peroxide and oxygen (reactions with oxygen are catalyzed by iron and manganese in the cloud droplets).

Acid deposition

Wet deposition

Wet deposition of acids occurs when any form of precipitation (rain,

snow, and so on.) removes acids from the atmosphere and delivers it to

the Earth's surface. This can result from the deposition of acids

produced in the raindrops (see aqueous phase chemistry above) or by the

precipitation removing the acids either in clouds or below clouds. Wet

removal of both gases and aerosols are both of importance for wet

deposition.

Dry deposition

Acid deposition also occurs via dry deposition in the absence of

precipitation. This can be responsible for as much as 20 to 60% of total

acid deposition. This occurs when particles and gases stick to the ground, plants or other surfaces.

Adverse effects

Acid rain has been shown to have adverse impacts on forests,

freshwaters and soils, killing insect and aquatic life-forms as well as

causing damage to buildings and having impacts on human health.

Surface waters and aquatic animals

Not

all fish, shellfish, or the insects that they eat can tolerate the same

amount of acid; for example, frogs can tolerate water that is more

acidic (i.e., has a lower pH) than trout.

Both the lower pH and higher aluminium concentrations in surface

water that occur as a result of acid rain can cause damage to fish and

other aquatic animals. At pH lower than 5 most fish eggs will not hatch

and lower pH can kill adult fish. As lakes and rivers become more acidic

biodiversity is reduced. Acid rain has eliminated insect life and some

fish species, including the brook trout in some lakes, streams, and creeks in geographically sensitive areas, such as the Adirondack Mountains of the United States.

However, the extent to which acid rain contributes directly or

indirectly via runoff from the catchment to lake and river acidity

(i.e., depending on characteristics of the surrounding watershed) is

variable. The United States Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA)

website states: "Of the lakes and streams surveyed, acid rain caused

acidity in 75% of the acidic lakes and about 50% of the acidic streams".

Lakes hosted by silicate basement rocks are more acidic than lakes

within limestone or other basement rocks with a carbonate composition

(i.e. marble) due to buffering effects by carbonate minerals, even with

the same amount of acid rain.

Soils

Soil biology and chemistry can be seriously damaged by acid rain. Some microbes are unable to tolerate changes to low pH and are killed. The enzymes of these microbes are denatured (changed in shape so they no longer function) by the acid. The hydronium ions of acid rain also mobilize toxins, such as aluminium, and leach away essential nutrients and minerals such as magnesium.

- 2 H+ (aq) + Mg2+ (clay) ⇌ 2 H+ (clay) + Mg2+ (aq)

Soil chemistry can be dramatically changed when base cations, such as

calcium and magnesium, are leached by acid rain thereby affecting

sensitive species, such as sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

Forests and other vegetation

Acid rain can have severe effects on vegetation. A forest in the Black Triangle in Europe.

Adverse effects may be indirectly related to acid rain, like the

acid's effects on soil (see above) or high concentration of gaseous

precursors to acid rain. High altitude forests are especially vulnerable

as they are often surrounded by clouds and fog which are more acidic

than rain.

Other plants can also be damaged by acid rain, but the effect on

food crops is minimized by the application of lime and fertilizers to

replace lost nutrients. In cultivated areas, limestone may also be added

to increase the ability of the soil to keep the pH stable, but this

tactic is largely unusable in the case of wilderness lands. When calcium

is leached from the needles of red spruce, these trees become less cold

tolerant and exhibit winter injury and even death.

Ocean acidification

Acid rain has a much less harmful effect on the oceans. Acid rain can

cause the ocean's pH to fall, making it more difficult for different

coastal species to create their exoskeletons

that they need to survive. These coastal species link together as part

of the ocean's food chain and without them being a source for other

marine life to feed off of more marine life will die.

Coral's limestone skeletal is sensitive to pH drop, because the calcium carbonate, core component of the limestone dissolves in acidic (low pH) solutions.

Human health effects

Acid rain does not directly affect human health. The acid in the

rainwater is too dilute to have direct adverse effects. The particulates

responsible for acid rain (sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides) do have

an adverse effect. Increased amounts of fine particulate matter in the

air contribute to heart and lung problems including asthma and bronchitis.

Other adverse effects

Effect of acid rain on statues

Acid rain and weathering

Acid rain can damage buildings, historic monuments, and statues, especially those made of rocks, such as limestone and marble,

that contain large amounts of calcium carbonate. Acids in the rain

react with the calcium compounds in the stones to create gypsum, which

then flakes off.

- CaCO3 (s) + H2SO4 (aq) ⇌ CaSO4 (s) + CO2 (g) + H2O (l)

The effects of this are commonly seen on old gravestones, where acid

rain can cause the inscriptions to become completely illegible. Acid

rain also increases the corrosion rate of metals, in particular iron, steel, copper and bronze.

Affected areas

Places significantly impacted by acid rain around the globe include

most of eastern Europe from Poland northward into Scandinavia, the eastern third of the United States, and southeastern Canada. Other affected areas include the southeastern coast of China and Taiwan.

Prevention methods

Technical solutions

Many coal-firing power stations use flue-gas desulfurization

(FGD) to remove sulfur-containing gases from their stack gases. For a

typical coal-fired power station, FGD will remove 95% or more of the SO2

in the flue gases. An example of FGD is the wet scrubber which is

commonly used. A wet scrubber is basically a reaction tower equipped

with a fan that extracts hot smoke stack gases from a power plant into

the tower. Lime or limestone in slurry form is also injected into the

tower to mix with the stack gases and combine with the sulfur dioxide

present. The calcium carbonate of the limestone produces pH-neutral calcium sulfate that is physically removed from the scrubber. That is, the scrubber turns sulfur pollution into industrial sulfates.

In some areas the sulfates are sold to chemical companies as gypsum when the purity of calcium sulfate is high. In others, they are placed in landfill.

The effects of acid rain can last for generations, as the effects of pH

level change can stimulate the continued leaching of undesirable

chemicals into otherwise pristine water sources, killing off vulnerable

insect and fish species and blocking efforts to restore native life.

Fluidized bed combustion also reduces the amount of sulfur emitted by power production.

Vehicle emissions control reduces emissions of nitrogen oxides from motor vehicles.

International treaties

International treaties on the long-range transport of atmospheric pollutants have been agreed for example, the 1985 Helsinki Protocol on the Reduction of Sulphur Emissions under the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution. Canada and the US signed the Air Quality Agreement in 1991. Most European countries and Canada have signed the treaties.

Emissions trading

In this regulatory scheme, every current polluting facility is given

or may purchase on an open market an emissions allowance for each unit

of a designated pollutant it emits. Operators can then install pollution

control equipment, and sell portions of their emissions allowances they

no longer need for their own operations, thereby recovering some of the

capital cost of their investment in such equipment. The intention is to

give operators economic incentives to install pollution controls.

The first emissions trading market was established in the United States by enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. The overall goal of the Acid Rain Program established by the Act is to achieve significant environmental and public health benefits through reductions in emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx),

the primary causes of acid rain. To achieve this goal at the lowest

cost to society, the program employs both regulatory and market based

approaches for controlling air pollution.