| Atrial fibrillation | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Auricular fibrillation |

| |

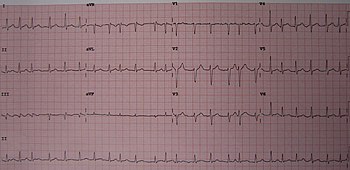

| Leads V4 and V5 of an electrocardiogram showing atrial fibrillation with somewhat irregular intervals between heart beats, no P waves, and a heart rate of about 150 BPM. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | None, heart palpitations, fainting, shortness of breath, chest pain |

| Complications | Heart failure, dementia, stroke |

| Usual onset | over age 50 |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure, valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, COPD, obesity, smoking, sleep apnea |

| Diagnostic method | Feeling the pulse, electrocardiogram |

| Differential diagnosis | Irregular heartbeat |

| Treatment | Rate control or rhythm control |

| Frequency | 2.5% (developed world), 0.5% (developing world) |

| Deaths | 193,300 with atrial flutter (2015) |

Atrial fibrillation (AF or A-fib) is an abnormal heart rhythm characterized by rapid and irregular beating of the atria. Often it starts as brief periods of abnormal beating which become longer and possibly constant over time. Often episodes have no symptoms. Occasionally there may be heart palpitations, fainting, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, or chest pain. The disease is associated with an increased risk of heart failure, dementia, and stroke. It is a type of supraventricular tachycardia.

High blood pressure and valvular heart disease are the most common alterable risk factors for AF. Other heart-related risk factors include heart failure, coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, and congenital heart disease. In the developing world valvular heart disease often occurs as a result of rheumatic fever. Lung-related risk factors include COPD, obesity, and sleep apnea. Other factors include excess alcohol intake, tobacco smoking, diabetes mellitus, and thyrotoxicosis. However, half of cases are not associated with any of these risks. A diagnosis is made by feeling the pulse and may be confirmed using an electrocardiogram (ECG). A typical ECG in AF shows no P waves and an irregular ventricular rate.

AF is often treated with medications to slow the heart rate to a near normal range (known as rate control) or to convert the rhythm to normal sinus rhythm (known as rhythm control). Electrical cardioversion can also be used to convert AF to a normal sinus rhythm and is often used emergently if the person is unstable. Ablation may prevent recurrence in some people. For those at low risk of stroke, no specific treatment is typically required, though aspirin or an anti-clotting medication may occasionally be considered. For those at more than low risk, an anti-clotting medication is typically recommended. Anti-clotting medications include warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants. Most people are at higher risk of stroke. While these medications reduce stroke risk, they increase rates of major bleeding.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common serious abnormal heart rhythm. In Europe and North America, as of 2014, it affects about 2 to 3% of the population. This is an increase from 0.4 to 1% of the population around 2005. In the developing world, about 0.6% of males and 0.4% of females are affected. The percentage of people with AF increases with age with 0.1% under 50 years old, 4% between 60 and 70 years old, and 14% over 80 years old being affected. A-fib and atrial flutter resulted in 193,300 deaths in 2015, up from 29,000 in 1990. The first known report of an irregular pulse was by Jean-Baptiste de Sénac in 1749. This was first documented by ECG in 1909 by Thomas Lewis.

Signs and symptoms

Normal rhythm tracing (top) Atrial fibrillation (bottom)

How a stroke can occur during atrial fibrillation

AF is usually accompanied by symptoms related to a rapid heart rate. Rapid and irregular heart rates may be perceived as the sensation of the heart beating too fast, irregularly, or skipping beats (palpitations) or exercise intolerance and occasionally may produce anginal chest pain (if the high heart rate causes the heart's demand for oxygen to increase beyond the supply of available oxygen (ischemia)). Other possible symptoms include congestive heart failure symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, or swelling. The abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia) is sometimes only identified with the onset of a stroke or a transient ischemic attack (TIA). It is not uncommon for a person to first become aware of AF from a routine physical examination or ECG, as it often does not cause symptoms.

Since most cases of AF are secondary to other medical problems, the presence of chest pain or angina, signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism (an overactive thyroid gland) such as weight loss and diarrhea, and symptoms suggestive of lung disease can indicate an underlying cause. A history of stroke or TIA, as well as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart failure, or rheumatic fever may indicate whether someone with AF is at a higher risk of complications. The risk of a blood clot forming in the left atrial chamber of the heart, breaking off, and then traveling in the bloodstream can be assessed using the CHADS2 score or CHA2DS2-VASc score.

Rapid heart rate

Presentation is similar to other forms of rapid heart rate and may be asymptomatic. Palpitations and chest discomfort are common complaints. The rapid uncoordinated heart rate may result in reduced output of blood pumped by the heart (cardiac output)

resulting in inadequate blood flow and therefore oxygen delivery to the

rest of the body. Common symptoms of uncontrolled atrial fibrillation

may include shortness of breath, shortness of breath when lying flat, dizziness, and sudden onset of shortness of breath during the night. This may progress to swelling of the lower extremities, a manifestation of congestive heart failure. Due to inadequate cardiac output, individuals with AF may also complain of light-headedness, may feel like they are about to faint, or may actually lose consciousness.

AF can cause respiratory distress due to congestion in the lungs. By definition, the heart rate will be greater than 100 beats per minute.

Blood pressure may be variable, and often difficult to measure as the

beat-by-beat variability causes problems for most digital

(oscillometric) non-invasive blood pressure monitors. For this reason, when determining heart rate in AF, direct cardiac auscultation is recommended. Low blood pressure

is most concerning and a sign that immediate treatment is required.

Many of the symptoms associated with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation

are a manifestation of congestive heart failure due to the reduced

cardiac output. Respiratory rate will be increased in the presence of

respiratory distress. Pulse oximetry may confirm the presence of too little oxygen reaching the body's tissues related to any precipitating factors such as pneumonia. Examination of the jugular veins may reveal elevated pressure (jugular venous distention). Examination of the lungs may reveal crackles, which are suggestive of pulmonary edema. Examination of the heart will reveal a rapid irregular rhythm.

Causes

Non-modifiable risk factors

(top left box) and modifiable risk factors (bottom left box) for atrial

fibrillation. The main outcomes of atrial fibrillation are in the right

box. BMI=Body Mass Index.

AF is linked to several forms of cardiovascular disease, but may

occur in otherwise normal hearts. Cardiovascular factors known to be

associated with the development of AF include high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, mitral valve stenosis (e.g., due to rheumatic heart disease or mitral valve prolapse), mitral regurgitation, left atrial enlargement, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), pericarditis, congenital heart disease, and previous heart surgery. Additionally, lung diseases (such as pneumonia, lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, and sarcoidosis) are thought to play a role in certain people. Disorders of breathing during sleep such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are also associated with AF. Obesity is a risk factor for AF. Hyperthyroidism and subclinical hyperthyroidism are associated with AF development. Caffeine consumption does not appear to be associated with AF, but excessive alcohol consumption ("binge drinking" or "holiday heart syndrome") is linked to AF. Sepsis also increases the risk of developing new-onset atrial fibrillation.

Long-term endurance exercise (e.g., long-distance bicycling or marathon

running) appears to be associated with a modest increase in the risk of

atrial fibrillation in middle-aged and elderly people. Tobacco smoking and secondhand tobacco smoke exposure are associated with an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation.

Genetics

A

family history of AF may increase the risk of AF. A study of more than

2,200 people found an increased risk factor for AF of 1.85 for those

that had at least one parent with AF. Various genetic mutations may be responsible.

Four types of genetic disorder are associated with atrial fibrillation:

- Familial AF as a monogenic disease

- Familial AF presenting in the setting of another inherited cardiac disease (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, familial amyloidosis)

- Inherited arrhythmic syndromes (congenital long QT syndrome, short QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome)

- Non-familial AF associated with genetic backgrounds (polymorphism in the ACE gene) that may predispose to atrial fibrillation

Family history in a first degree relative is associated with a 40% increase in risk of AF. This finding led to the mapping of different loci such as 10q22-24, 6q14-16 and 11p15-5.3 and discover mutations associated with the loci. Fifteen mutations of gain and loss of function have been found in the genes of K+ channels, including mutations in KCNE1-5, KCNH2, KCNJ5 or ABCC9 among others. Six variations in genes of Na+ channels that include SNC1-4B, SNC5A and SNC10A have also been found. All of these mutations affect the processes of polarization-depolarization of the myocardium, cellular hyper-excitability, shortening of effective refractory period favouring re-entries.

Other mutations in genes, such as GJA5, affect Gap junctions, generating a cellular uncoupling that promotes re-entries and a slow conduction velocity.

Using genome-wide association study, which screen the entire genome for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), three susceptibility loci have been found for AF (4q25, 1q21 and 16q22). In these loci there are SNPs associated with a 30% increase in risk of recurrent atrial tachycardia after ablation. There is also SNPs associated with loss of function of the Pitx2c gene (involved in cellular development of pulmonary valves), responsible for re-entries. There are also SNPs close to ZFHX3 genes involved in the regulation of Ca2+.

A GWAS meta-analysis

study conducted in 2018 revealed the discovery of 70 new loci

associated with AF. Different variants have been identified. They are

associated with genes that encode transcription factors, such as TBX3 and TBX5, NKX2-5 or PITX2, involved in the regulation of cardiac conduction, modulation of ion channels and in cardiac development. Have been also identified new genes involved in tachycardia (CASQ2) or associated with an alteration in cardiomyocyte communication (PKP2).

Sedentary lifestyle

A sedentary lifestyle increases the risk factors associated with AF such as obesity, hypertension or diabetes mellitus. This favors remodeling processes of the atrium due to inflammation or alterations in the depolarization of cardiomyocytes by elevation of sympathetic nervous system activity. A sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increased risk of AF compared to physical activity. In both men and women, the practice of moderate exercise reduces the risk of AF progressively, but intense sports may increase the risk of developing AF, as seen in athletes. It is due to a remodeling of cardiac tissue, and an increase in vagal tone, which shortens the effective refractory period (ERP) favoring re-entries from the pulmonary veins.

High blood pressure

According to the CHARGE Consortium both systolic and diastolic blood pressure

are predictors of the risk of AF. Systolic blood pressure values close

to normal limit the increase in the risk associated with AF. Diastolic

dysfunction is also associated with AF, which increased pressure, left atrial volume, size, and left ventricular hypertrophy, characteristic of chronic hypertension. All atrial remodeling is related to a heterogeneous conduction and the formation of re-entrant electric conduction from the pulmonary veins.

Tobacco

The rate of AF in smokers is 1.4 times higher than in non-smokers. Tobacco use increases susceptibility to AF through different processes. Exposure to tobacco products increases the release of catecholamines (e.g., epinephrine or norepinephrine) and promotes narrowing of the coronary arteries, leading to inadequate blood flow and oxygen delivery to the heart. In addition, it accelerates atherosclerosis, due to its effect of oxidative stress on lipids and inflammation, which leads to the formation of blood clots. Finally, nicotine induces the formation of patterns of collagen type III in the atrium and has profibrotic effects. All this modifies the atrial tissue, favoring the re-entry.

Other diseases

There is a relationship between risk factors such as obesity and hypertension, with the appearance of diseases such as diabetes mellitus and sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome, specifically, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). These diseases are associated with an increased risk of AF due to their remodeling effects on the left atrium.

Pathophysiology

The normal electrical conduction system of the heart allows the impulse that is generated by the sinoatrial node (SA node) of the heart to be propagated to and stimulate the myocardium

(muscular layer of the heart). When the myocardium is stimulated, it

contracts. It is the ordered stimulation of the myocardium that allows

efficient contraction of the heart, thereby allowing blood to be pumped

to the body.

In AF, the normal regular electrical impulses generated by the sinoatrial node in the right atrium of the heart are overwhelmed by disorganized electrical impulses usually originating in the roots of the pulmonary veins. This leads to irregular conduction of ventricular impulses that generate the heartbeat.

Pathology

The

primary pathologic change seen in atrial fibrillation is the

progressive fibrosis of the atria. This fibrosis is due primarily to

atrial dilation; however, genetic causes and inflammation may be factors

in some individuals. Dilation of the atria can be due to almost any

structural abnormality of the heart that can cause a rise in the

pressure within the heart. This includes valvular heart disease (such as mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation, and tricuspid regurgitation),

hypertension, and congestive heart failure. Any inflammatory state that

affects the heart can cause fibrosis of the atria. This is typically

due to sarcoidosis but may also be due to autoimmune disorders that

create autoantibodies against myosin heavy chains. Mutation of the lamin AC gene is also associated with fibrosis of the atria that can lead to atrial fibrillation.

Once dilation of the atria has occurred, this begins a chain of events that leads to the activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and subsequent increase in matrix metalloproteinases and disintegrin,

which leads to atrial remodeling and fibrosis, with loss of atrial

muscle mass. This process occurs gradually, and experimental studies

have revealed patchy atrial fibrosis may precede the occurrence of

atrial fibrillation and may progress with prolonged durations of atrial

fibrillation.

Fibrosis is not limited to the muscle mass of the atria and may occur in the sinus node (SA node) and atrioventricular node (AV node), correlating with sick sinus syndrome. Prolonged episodes of atrial fibrillation have been shown to correlate with prolongation of the sinus node recovery time, suggesting that dysfunction of the SA node is progressive with prolonged episodes of atrial fibrillation.

Electrophysiology

| Conduction | ||

| Sinus rhythm | Atrial fibrillation | |

There are multiple theories about the cause of atrial fibrillation.

An important theory is that, in atrial fibrillation, the regular

impulses produced by the sinus node for a normal heartbeat are

overwhelmed by rapid electrical discharges produced in the atria and

adjacent parts of the pulmonary veins.

Sources of these disturbances are either automatic foci, often

localized at one of the pulmonary veins, or a small number of localized

sources in the form of either a re-entrant leading circle, or electrical

spiral waves (rotors); these localized sources may be found in the left

atrium near the pulmonary veins or in a variety of other locations

through both the left or right atrium. There are three fundamental

components that favor the establishment of a leading circle or a rotor:

slow conduction velocity of cardiac action potential, short refractory period, and small wavelength.

Meanwhile, wavelength is the product of velocity and refractory period.

If the action potential has fast conduction, with a long refractory

period and/or conduction pathway shorter than the wavelength, an AF

focus would not be established. In multiple wavelet theory, a wavefront

will break into smaller daughter wavelets when encountering an obstacle,

through a process called vortex shedding; but under proper conditions,

such wavelets can reform and spin around a centre, forming an AF focus.

In a heart with AF, the increased calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum and increased calcium sensitivity can lead to accumulation of intra-cellular calcium and causes down regulation of L-type calcium channels.

This reduces the duration of action potential and refractory period,

thus favorable for the conduction of re-entrant waves. Increased

expression of inward-rectifier potassium ion channels can cause a reduced atrial refractory period and wavelength. The abnormal distribution of gap junction proteins such as GJA1 (also known as Connexin 43), and GJA5 (Connexin 40) causes non-uniformity of electrical conduction, thus causing arrhythmia.

AF can be distinguished from atrial flutter

(AFL), which appears as an organized electrical circuit usually in the

right atrium. AFL produces characteristic saw-toothed F-waves of

constant amplitude and frequency on an ECG

whereas AF does not. In AFL, the discharges circulate rapidly at a rate

of 300 beats per minute (bpm) around the atrium. In AF, there is no

regularity of this kind, except at the sources where the local

activation rate can exceed 500 bpm.

Although the electrical impulses of AF occur at a high rate, most

of them do not result in a heart beat. A heart beat results when an

electrical impulse from the atria passes through the atrioventricular (AV) node

to the ventricles and causes them to contract. During AF, if all of the

impulses from the atria passed through the AV node, there would be

severe ventricular tachycardia, resulting in a severe reduction of cardiac output.

This dangerous situation is prevented by the AV node since its limited

conduction velocity reduces the rate at which impulses reach the

ventricles during AF.

Diagnosis

A 12-lead ECG showing atrial fibrillation at approximately 150 beats per minute

Diagram of normal sinus rhythm as seen on ECG. In atrial fibrillation the P waves, which represent depolarization of the top of the heart, are absent.

The evaluation of atrial fibrillation involves a determination of the

cause of the arrhythmia, and classification of the arrhythmia.

Diagnostic investigation of AF typically includes a complete history and

physical examination, ECG, transthoracic echocardiogram, complete blood count, and serum thyroid stimulating hormone level.

Screening

The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to determine the usefulness of screening in 2018.

Limited studies have suggested that screening for atrial fibrillation

in those 65 years and older increases the number of cases of atrial

fibrillation detected.

Minimal evaluation

In

general, the minimal evaluation of atrial fibrillation should be

performed in all individuals with AF. The goal of this evaluation is to

determine the general treatment regimen for the individual. If results

of the general evaluation warrant it, further studies may then be

performed.

History and physical examination

The

history of the individual's atrial fibrillation episodes is probably

the most important part of the evaluation. Distinctions should be made

between those who are entirely asymptomatic when they are in AF (in

which case the AF is found as an incidental finding on an ECG or

physical examination) and those who have gross and obvious symptoms due

to AF and can pinpoint whenever they go into AF or revert to sinus

rhythm.

Routine bloodwork

While many cases of AF have no definite cause, it may be the result of various other problems. Hence, kidney function and electrolytes are routinely determined, as well as thyroid-stimulating hormone (commonly suppressed in hyperthyroidism and of relevance if amiodarone is administered for treatment) and a blood count.

In acute-onset AF associated with chest pain, cardiac troponins or other markers of damage to the heart muscle may be ordered. Coagulation studies (INR/aPTT) are usually performed, as anticoagulant medication may be commenced.

Electrocardiogram

ECG

of atrial fibrillation (top) and normal sinus rhythm (bottom). The

purple arrow indicates a P wave, which is lost in atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation is diagnosed on an electrocardiogram (ECG), an

investigation performed routinely whenever an irregular heart beat is

suspected. Characteristic findings are the absence of P waves, with

disorganized electrical activity in their place, and irregular R–R

intervals due to irregular conduction of impulses to the ventricles. At very fast heart rates, atrial fibrillation may look more regular, which may make it more difficult to separate from other supraventricular tachycardias or ventricular tachycardia.

QRS complexes should be narrow, signifying that they are initiated by normal conduction of atrial electrical activity through the intraventricular conduction system.

Wide QRS complexes are worrisome for ventricular tachycardia, although,

in cases where there is a disease of the conduction system, wide

complexes may be present in A-fib with rapid ventricular response.

If paroxysmal AF is suspected but an ECG during an office visit

shows only a regular rhythm, AF episodes may be detected and documented

with the use of ambulatory Holter monitoring

(e.g., for a day). If the episodes are too infrequent to be detected by

Holter monitoring with reasonable probability, then the person can be

monitored for longer periods (e.g., a month) with an ambulatory event monitor.

Echocardiography

In general, a non-invasive transthoracic echocardiogram

(TTE) is performed in newly diagnosed AF, as well as if there is a

major change in the person's clinical state. This ultrasound-based scan

of the heart may help identify valvular heart disease

(which may greatly increase the risk of stroke and alter

recommendations for the appropriate type of anticoagulation), left and

right atrial size (which indicates likelihood that AF may become

permanent), left ventricular size and function, peak right ventricular

pressure (pulmonary hypertension), presence of left atrial thrombus (low sensitivity), presence of left ventricular hypertrophy and pericardial disease.

Significant enlargement of both the left and right atria is

associated with long-standing atrial fibrillation and, if noted at the

initial presentation of atrial fibrillation, suggests that the atrial

fibrillation is likely to be of a longer duration than the individual's

symptoms.

Extended evaluation

In

general, an extended evaluation is not necessary for most individuals

with atrial fibrillation and is performed only if abnormalities are

noted in the limited evaluation, if a reversible cause of the atrial

fibrillation is suggested, or if further evaluation may change the

treatment course.

Chest X-ray

In general, a chest X-ray

is performed only if a pulmonary cause of atrial fibrillation is

suggested, or if other cardiac conditions are suspected (in particular congestive heart failure.) This may reveal an underlying problem in the lungs or the blood vessels in the chest.

In particular, if an underlying pneumonia is suggested, then treatment

of the pneumonia may cause the atrial fibrillation to terminate on its

own.

Transesophageal echocardiogram

A regular echocardiogram (transthoracic echo/TTE) has a low sensitivity for identifying blood clots in the heart. If this is suspected (e.g., when planning urgent electrical cardioversion) a transesophageal echocardiogram/TEE (or TOE where British spelling is used) is preferred.

The TEE has much better visualization of the left atrial appendage than transthoracic echocardiography. This structure, located in the left atrium, is the place where a blood clot forms in more than 90% of cases in non-valvular (or non-rheumatic) atrial fibrillation.

TEE has a high sensitivity for locating thrombi in this area and can

also detect sluggish bloodflow in this area that is suggestive of blood

clot formation.

If a blood clot is seen on TEE, then cardioversion is

contraindicated due to the risk of stroke and anticoagulation is

recommended.

Ambulatory Holter monitoring

A Holter monitor

is a wearable ambulatory heart monitor that continuously monitors the

heart rate and heart rhythm for a short duration, typically 24 hours. In

individuals with symptoms of significant shortness of breath with

exertion or palpitations on a regular basis, a Holter monitor may be of

benefit to determine whether rapid heart rates (or unusually slow heart

rates) during atrial fibrillation are the cause of the symptoms.

Exercise stress testing

Some

individuals with atrial fibrillation do well with normal activity but

develop shortness of breath with exertion. It may be unclear whether the

shortness of breath is due to a blunted heart rate response to exertion

caused by excessive atrioventricular node-blocking

agents, a very rapid heart rate during exertion, or other underlying

conditions such as chronic lung disease or coronary ischemia. An exercise stress test

will evaluate the individual's heart rate response to exertion and

determine if the AV node blocking agents are contributing to the

symptoms.

Classification

| AF category | Defining characteristics |

|---|---|

| First detected | only one diagnosed episode |

| Paroxysmal | recurrent episodes that stop on their own in less than 7 days |

| Persistent | recurrent episodes that last more than 7 days |

| Permanent | an ongoing long-term episode |

The American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend in their guidelines the following classification system based on simplicity and clinical relevance.

All people with AF are initially in the category called first detected AF.

These people may or may not have had previous undetected episodes. If a

first detected episode stops on its own in less than 7 days and then

another episode begins, later on, the category changes to paroxysmal AF.

Although people in this category have episodes lasting up to 7 days, in

most cases of paroxysmal AF the episodes will stop in less than

24 hours. If the episode lasts for more than 7 days, it is unlikely to

stop on its own, and is then known as persistent AF. In this case,

cardioversion can be used to stop the episode. If cardioversion is

unsuccessful or not attempted and the episode continues for a long time

(e.g., a year or more), the person's AF is then known as permanent.

Episodes that last less than 30 seconds are not considered in

this classification system. Also, this system does not apply to cases

where the AF is a secondary condition that occurs in the setting of a

primary condition that may be the cause of the AF.

About half of people with AF have permanent AF, while a quarter have paroxysmal AF, and a quarter have persistent AF.

In addition to the above four AF categories, which are mainly

defined by episode timing and termination, the ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines

describe additional AF categories in terms of other characteristics of

the person.

- Lone atrial fibrillation (LAF) – absence of clinical or echocardiographic findings of other cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), related pulmonary disease, or cardiac abnormalities such as enlargement of the left atrium, and age under 60 years

- Nonvalvular AF – absence of rheumatic mitral valve disease, a prosthetic heart valve, or mitral valve repair

- Secondary AF – occurs in the setting of a primary condition that may be the cause of the AF, such as acute myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery, pericarditis, myocarditis, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, or other acute pulmonary disease

Lastly, atrial fibrillation is also classified by whether or not it

is caused by valvular heart disease. Valvular atrial fibrillation refers

to atrial fibrillation attributable to moderate to severe mitral valve stenosis or atrial fibrillation in the presence of a mechanical artificial heart valve.

This distinction is necessary since it has implications on appropriate

treatment including differing recommendations for anticoagulation.

Management

The main goals of treatment are to prevent circulatory instability and stroke. Rate or rhythm control are used to achieve the former, whereas anticoagulation is used to decrease the risk of the latter. If cardiovascularly unstable due to uncontrolled tachycardia, immediate cardioversion is indicated. Regular, moderate-intensity exercise is beneficial for people with AF as is weight loss.

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulation

can be used to reduce the risk of stroke from AF. Anticoagulation is

recommended in most people other than those at low risk of stroke

or those at high risk of bleeding. The risk of falls and consequent

bleeding in frail elderly people should not be considered a barrier to

initiating or continuing anticoagulation since the risk of fall-related

brain bleeding is low and the benefit of stroke prevention often

outweighs the risk of bleeding.

Oral anticoagulation is underused in atrial fibrillation while aspirin

is overused in many who should be treated with a direct oral

anticoagulants (DOACs) or warfarin. In 2019, DOACs were often recommended over warfarin by the American Heart Association.

The risk of stroke from non-valvular AF can be estimated using the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

A 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline said that for nonvalvular AF,

anticoagulation is recommended if there is a score of 2 or more, and may

be considered if there is a score of 1 in men or 2 in women, and not

using anticoagulation is reasonable if there is a score of 0 in men or 1

in women. Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians, Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, Canadian Cardiovascular Society, European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Circulation Society, Korean Heart Rhythm Society, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

recommend the use of novel oral anticoagulants or warfarin with a

CHADS2VASC score of 1 over aspirin and some directly recommend against

aspirin.

Experts generally advocate for most people with atrial fibrillation

with CHADS2VASC scores of 1 or more receiving anticoagulation though

aspirin is sometimes used for people with a CHADS2VASC score of 1

(moderate risk for stroke).

There is little evidence to support the idea that the use of aspirin

significantly reduces the risk of stroke in people with atrial

fibrillation.

Furthermore, aspirin's major bleeding risk (including bleeding in the

brain) is similar to that of warfarin and NOACs despite its inferior

efficacy.

Anticoagulation can be achieved through a number of means including warfarin, heparin, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and apixaban.

A number of issues should be considered, including the cost of NOACs,

risk of stroke, risk of falls, comorbidities (such as chronic liver or

kidney disease), the presence of significant mitral stenosis or

mechanical heart valves, compliance, and speed of desired onset of

anticoagulation.

For those with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, NOACs

(rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban) are at least as effective as

warfarin for preventing strokes and blood clots embolizing to the systemic circulation (if not more so) and are generally preferred over warfarin. NOACS carry a lower risk of bleeding in the brain compared to warfarin, although dabigatran is associated with a higher risk of intestinal bleeding. Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is inferior to warfarin for preventing strokes and has comparable bleeding risk in people with atrial fibrillation. In those who are also on aspirin, however, NOACs appear to be better than warfarin.

Warfarin is the recommended anticoagulant choice for persons with

valvular atrial fibrillation (atrial fibrillation in the presence of a

mechanical heart valve and/or moderate-severe mitral valve stenosis). The exception to this recommendation is in people with valvular atrial fibrillation who are unable to maintain a therapeutic INR on warfarin therapy; in such cases, treatment with a NOAC is then recommended.

Rate versus rhythm control

There

are two ways to approach atrial fibrillation using medications: rate

control and rhythm control. Both methods have similar outcomes. Rate control lowers the heart rate closer to normal, usually 60 to 100 bpm, without trying to convert to a regular rhythm. Rhythm control

tries to restore a normal heart rhythm in a process called

cardioversion and maintains the normal rhythm with medications. Studies

suggest that rhythm control is more important in the acute setting AF,

whereas rate control is more important in the chronic phase.

The risk of stroke appears to be lower with rate control versus attempted rhythm control, at least in those with heart failure.

AF is associated with a reduced quality of life, and, while some

studies indicate that rhythm control leads to a higher quality of life,

some did not find a difference.

Neither rate nor rhythm control is superior in people with heart

failure when they are compared in various clinical trials. However, rate

control is recommended as the first line treatment regimen for people

with heart failure. On the other hand, rhythm control is only

recommended when people experience persistent symptoms despite adequate

rate control therapy.

In those with a fast ventricular response, intravenous magnesium significantly increases the chances of successful rate and rhythm control in the urgent setting without major side-effects.

A person with poor vital signs, mental status changes, preexcitation,

or chest pain often will go to immediate treatment with synchronized DC

cardioversion.

Otherwise the decision of rate control versus rhythm control using

drugs is made. This is based on a number of criteria that includes

whether or not symptoms persist with rate control.

Rate control

Rate control to a target heart rate of less than 110 beats per minute is recommended in most people. Lower heart rates may be recommended in those with left ventricular hypertrophy or reduced left ventricular function. Rate control is achieved with medications that work by increasing the degree of block at the level of the AV node, decreasing the number of impulses that conduct into the ventricles. This can be done with:

- Beta blockers (preferably the "cardioselective" beta blockers such as metoprolol, bisoprolol, or nebivolol)

- Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem or verapamil)

- Cardiac glycosides (e.g., digoxin) – have less use, apart from in older people who are sedentary. They are not as effective as either beta blockers or calcium channel blockers.

In those with chronic disease either beta blockers or calcium channel blockers are recommended.

In addition to these agents, amiodarone has some AV node blocking

effects (in particular when administered intravenously), and can be

used in individuals when other agents are contraindicated or ineffective

(particularly due to hypotension).

Cardioversion

Cardioversion is the attempt to switch an irregular heartbeat to a normal heartbeat using electrical or chemical means.

- Electrical cardioversion involves the restoration of normal heart rhythm through the application of a DC electrical shock. Exact placement of the pads does not appear to be important.

- Chemical cardioversion is performed with medications, such as amiodarone, dronedarone, procainamide (especially in pre-excited atrial fibrillation), dofetilide, ibutilide, propafenone, or flecainide.

After successful cardioversion the heart may be in a stunned state,

which means that there is a normal rhythm but restoration of normal

atrial contraction has not yet occurred.

Surgery

Ablation

In

young people with little-to-no structural heart disease where rhythm

control is desired and cannot be maintained by medication or

cardioversion, then radiofrequency catheter ablation or cryoablation may be attempted and is preferred over years of drug therapy.

Although radiofrequency ablation is becoming an accepted intervention

in selected younger people, there is currently a lack of evidence that

ablation reduces all-cause mortality, stroke, or heart failure.

There are two ongoing clinical trials (CABANA [Catheter Ablation Versus

Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation] and EAST [Early

Therapy of Atrial Fibrillation for Stroke Prevention Trial]) that should

provide new information for assessing whether AF catheter ablation is

superior to more standard therapy.

The Maze procedure,

first performed in 1987, is an effective invasive surgical treatment

that is designed to create electrical blocks or barriers in the atria of

the heart, forcing electrical impulses that stimulate the heartbeat to

travel down to the ventricles. The idea is to force abnormal electrical

signals to move along one, uniform path to the lower chambers of the

heart (ventricles), thus restoring the normal heart rhythm.

AF often occurs after cardiac surgery and is usually

self-limiting. It is strongly associated with age, preoperative

hypertension, and the number of vessels grafted. Measures should be

taken to control hypertension preoperatively to reduce the risk of AF.

Also, people with a higher risk of AF, e.g., people with pre-operative

hypertension, more than 3 vessels grafted, or greater than 70 years of

age, should be considered for prophylactic treatment. Postoperative

pericardial effusion is also suspected to be the cause of atrial

fibrillation. Prophylaxis may include prophylactic postoperative rate

and rhythm management. Some authors perform posterior pericardiotomy to

reduce the incidence of postoperative AF.

When AF occurs, management should primarily be rate and rhythm control.

However, cardioversion may be employed if the person is hemodynamically

unstable, highly symptomatic, or persists for 6 weeks after discharge.

In persistent cases, anticoagulation should be used.

Left atrial appendage occlusion

There is tentative evidence that left atrial appendage occlusion therapy may reduce the risk of stroke in people with non-valvular AF as much as warfarin.

After surgery

After catheter ablation, people are moved to a cardiac recovery unit, intensive care unit,

or cardiovascular intensive care unit where they are not allowed to

move for 4–6 hours. Minimizing movement helps prevent bleeding from the

site of the catheter insertion. The length of time people stay in

hospital varies from hours to days. This depends on the problem, the

length of the operation and whether or not general anaesthetic was used.

Additionally, people should not engage in strenuous physical activity –

to maintain a low heart rate and low blood pressure – for around six

weeks.

Prognosis

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of heart failure by 11 per 1000, kidney problems by 6 per 1000, death by 4 per 1000, stroke by 3 per 1000, and coronary heart disease by 1 per 1000. Women have a worse outcome overall than men. Evidence increasingly suggests that atrial fibrillation is independently associated with a higher risk of developing dementia.

Blood clots

Prediction of embolism

Determining the risk of an embolism causing a stroke is important for guiding the use of anticoagulants. The most accurate clinical prediction rules are:

Both the CHADS2 and the CHA2DS2-VASc

score predict future stroke risk in people with A-fib with CHA2DS2-VASc

being more accurate. Some that had a CHADS2 score of 0 had a

CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3, with a 3.2% annual risk of stroke. Thus a

CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 is considered very low risk.

Mechanism of thrombus formation

In

atrial fibrillation, the lack of an organized atrial contraction can

result in some stagnant blood in the left atrium (LA) or left atrial appendage (LAA). This lack of movement of blood can lead to thrombus formation (blood clotting). If the clot becomes mobile and is carried away by the blood circulation, it is called an embolus. An embolus proceeds through smaller and smaller arteries until it plugs one of them and prevents blood from flowing through the artery. This process results in end organ damage due to loss of nutrients, oxygen, and removal of cellular waste products. Emboli in the brain may result in an ischemic stroke or a transient ischemic attack (TIA).

More than 90% of cases of thrombi associated with non-valvular atrial fibrillation evolve in the left atrial appendage.

However, the LAA lies in close relation to the free wall of the left

ventricle and thus the LAA's emptying and filling, which determines its

degree of blood stagnation, may be helped by the motion of the wall of

the left ventricle, if there is good ventricular function.

If the LA is enlarged, there is an increased risk of thrombi that originate in the LA. Moderate to severe, non-rheumatic, mitral regurgitation (MR) reduces this risk of stroke. This risk reduction may be due to a beneficial swirling effect of the MR blood flow into the LA.

Dementia

Atrial fibrillation has been independently associated with a higher risk of dementia.

Several mechanisms for this association have been proposed including

silent small blood clots (subclinical microthrombi) traveling to the

brain resulting in small ischemic strokes without symptoms, altered blood flow to the brain, inflammation, and genetic factors.

Effective anticoagulation with novel oral anticoagulants or warfarin

appears to be protective against AF-associated dementia and evidence of

silent ischemic strokes on MRI.

Epidemiology

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia. In Europe and North America, as of 2014, it affects about 2% to 3% of the population. This is an increase from 0.4 to 1% of the population around 2005. In the developing world, rates are about 0.6% for males and 0.4% for females.

The number of people diagnosed with AF has increased due to better

detection of silent AF and increasing age and conditions that predispose

to it.

It also accounts for one-third of hospital admissions for cardiac rhythm disturbances, and the rate of admissions for AF has risen in recent years. Strokes from AF account for 20–30% of all ischemic strokes. After a transient ischemic attack or stroke about 11% are found to have a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Between 3 and 11% of those with AF have structurally normal hearts. Approximately 2.2 million individuals in the United States and 4.5 million in the European Union have AF.

The number of new cases each year of atrial fibrillation

increases with age. In individuals over the age of 80, it affects about

8%.

As of 2001 it was anticipated that in developed countries, the number

of people with atrial fibrillation was likely to increase during the

following 50 years, owing to the growing proportion of elderly

individuals.

Sex

It is more common in men than in women, in European and North American populations. In Asian populations and in both developed and developing countries,

there is also a higher rate in men than in women. The risk factors

associated with AF are also distributed differently according to sex. In

men, coronary disease is more frequent, while in women, high systolic blood pressure or valvular heart disease are more prevalent.

Ethnicity

Rates

of AF are lower in populations of African descent than in populations

of European descent. The African descent is associated with a protective

effect of AF, due to the low presence of SNPs with guanine alleles, in comparison with the European ancestry. European ancestry has more frequent mutations. The variant rs4611994 for the gene PITX2 is associated with risk of AF in African and European populations.

Other studies reveal that Hispanic and Asian populations have a lower

risk of AF compared to populations of European descent. In addition,

they demonstrate that the risk of AF in non-European populations is

associated with characteristic risk factors of these populations, such

as hypertension.

History

Because

the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation requires measurement of the

electrical activity of the heart, atrial fibrillation was not truly

described until 1874, when Edmé Félix Alfred Vulpian observed the irregular atrial electrical behavior that he termed "fremissement fibrillaire" in dog hearts. In the mid-eighteenth century, Jean-Baptiste de Sénac made note of dilated, irritated atria in people with mitral stenosis. The irregular pulse associated with AF was first recorded in 1876 by Carl Wilhelm Hermann Nothnagel and termed "delirium cordis",

stating that "[I]n this form of arrhythmia the heartbeats follow each

other in complete irregularity. At the same time, the height and tension

of the individual pulse waves are continuously changing". Correlation of delirium cordis with the loss of atrial contraction as reflected in the loss of a waves in the jugular venous pulse was made by Sir James MacKenzie in 1904. Willem Einthoven published the first ECG showing AF in 1906.

The connection between the anatomic and electrical manifestations of AF

and the irregular pulse of delirium cordis was made in 1909 by Carl

Julius Rothberger, Heinrich Winterberg, and Sir Thomas Lewis.