Typical canvassing material for GOTV in the U.S.

"Get out the vote" (or "getting out the vote"; GOTV) describes efforts aimed at increasing the voter turnout in elections. In countries that do not have or enforce compulsory voting,

voter turnout can be low, sometimes even below a third of the eligible

voter pool. GOTV is generally not required for elections when there are

effective compulsory voting systems in place, other than perhaps to

register first time voters.

There may be two types of political campaigns. The first is voter registration campaigns

by electoral authorities or nonpartisan organizations that attempt to

motivate potential voters to register and to vote. The second type is

efforts made by political parties or politicians targeted at registered

voters who are expected to vote in their favor. Campaigns typically

attempt to register voters, then get them to vote, either by absentee

ballot, early voting or election day voting.

Campaign contexts

In

contexts of the efforts of candidates, party activities and ballot

measure campaigns, "get-out-the-vote" or "GOTV" is an adjective

indicating having the effect of increasing the number of the campaign's supporters who will vote in the immediately approaching election.

Typically GOTV is a distinct phase of the overall campaign. Tactics used during GOTV often include: telephoning or sending personalized audio messages

to known supporters on the days leading up to an election (or on

election day itself), providing transport to and from polling stations

for supporters, and canvassing known supporters.

Canvassing for the purpose of voter registration

usually ceases when GOTV begins. Other activities include literature

drops early on election day or the evening before and an active tracking

of eligible voters who have already voted.

The importance of get out the vote efforts increases as the total

percentage of the population voting decreases. For instance, with only

two-thirds of the population voting in a Canadian election it is often

easier and more cost effective to ensure that a hundred supporters show

up on polling day than it is to convince a hundred voters to switch

support from one party to the other. This situation often leads to

polarized electoral politics. A 90% turnout from a party's radical base

is often better than a 50 percent turnout from both radical and moderate

supporters.

GOTV can also be important in high turn-out elections when the margin of victory is expected to be close.

Voter turnout organizations

In many countries, the task of electoral authorities

includes the promotion of and assisting in the registration of

potential voters, and in the exercise of the right to vote. However,

such efforts are not uniformly successful, and at times are partisan.

A number of nonpartisan

voter turnout organizations have formed in an effort to "get out the

vote". In the United States, such voter turnout organizations include

the League of Women Voters, Rock the Vote, The Voter Participation Center and Vote.org,

which attempt to motivate potential voters to register and to vote in

the belief that failure of any eligible voter to vote in any election is

a loss to society.

During 2016 Georgian parliamentary election President of Georgia Giorgi Margvelashvili supported an unprecedented Get out the vote campaign in Georgian history in terms of the scale of coverage, feedbacks, and results - a nation-wide campaign initiated by the Europe-Georgia Institute to increase involvement of youth in the elections.

Shortly before the elections the Europe-Georgia Institute started the "Your Voice, Our Future" (YVOF Campaign) in the village of Bazaleti. President Margvelashvil and George Melashvili, the head of the Europe-Georgia Institute

addressed participants. Shortly after summer schools on civic

engagement, political culture and "Get out the vote" campaigns were held

in 10 different regions of Georgia.

participants visited 20 cities and towns and held meetings with locals,

describing and explaining the importance of voting. Young people

planned creative activities such as Flash mobs, plays, theatre sketches and attracted media attention.

The effort of these organizations is in getting people to vote

and not to promote particular candidates or political view, and a group

is nonpartisan if it is not directing people how to vote. Nonpartisan

groups generally do not distribute literature about candidates or causes

when assisting potential voters to register to vote, and also do not

focus GOTV efforts on voters who are most likely to agree with their

personal views.

Reading system

The traditional GOTV method used in the UK is the Reading system, developed by the Reading Constituency Labour Party and its MP Ian Mikardo for the 1945 general election. Once canvassing

was performed to identify likely Labour voters, these were compiled

onto 'Reading pads' or 'Mikardo sheets' featuring the names and

addresses of supporters and pasted onto a large table or plank of wood.

On election day these lists, with identical copies underneath, were torn

off and given to GOTV campaigners. Lists of this type are sometimes

referred to as Shuttleworths.

At each polling station, tellers for each party will collect the

unique poll numbers of voters from their polling cards. These numbers

are regularly collected from the polling stations and collated in a

campaign headquarters for each ward, often referred to in the UK as a

committee room. 'Promised voters' who have already voted are then

crossed off the list of voters canvassed as supporting Labour. This

enables campaigners to then focus more efficiently on the remainder of

their supporters who have not voted. Computerisation has heralded

further increases in efficiency, but nearly all subsequent methodologies

can be traced back in some form to the Reading system.

Negative campaigning and voter suppression

Robby Mook get out the vote leaflet for the Maryland gubernatorial election.

The terminology reflects a distinction of GOTV from the complementary

strategy of suppressing turnout among likely opposition voters. Political consultants are reputed to privately advise some candidates to "go negative"

(attack an opponent), without any intent to sway voters toward them:

this plan is to instead increase the number of eligible voters who fail to vote, because their tendency to believe "politics is inherently corrupt" has so recently been reinforced. Such turnout suppression can be advantageous where any combination of three conditions apply:

- The negative campaigning is targeted (by direct mail, telephone "push polls," or the like) on likely opposing voters, reducing the collateral damage to supporters' morale.

- The side going negative has an advantage in its supporters being steadier voters than those of its opponent.

- The side going negative has an advantage in doing effective GOTV, so

that its campaign workers can get a GOTV "antidote" to more supporters

"poisoned" by the negative campaign, than the opposing campaign can of

their own supporters.

Vote by mail

Face to face GOTV has been found to be less effective with Vote by mail balloting.

Get out the vote in practice

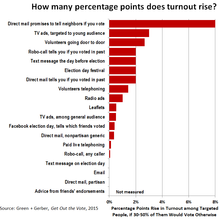

Methods of raising turnout.

Political scientists have conducted hundreds of field experiments to learn which get out the vote tactics are effective, when, and on which types of voters. This research has revolutionized how campaigns conceive of their get out the vote efforts.

Research also shows that voting is habit-forming, as voting in one

election increases the probability of voting in a future election by 10

percentage points (controlling for other factors).

The value of GOTV is unclear, but a well-organized effort can

gain a candidate as much as nine percentage points in campaigns in the

United States.

In terms of mobilization, studies have found that door-to-door

canvassing increases turnout among the contacted households with

approximately 4.3 percentage points, according to experts Alan Gerber

and Gregory Huber in 2016

while a 2013 study of 71 canvasses including many that targeted low

propensity voters found turnout increased by 2–3 percentage points. Even earlier, analysts had often concluded that personal canvassing produced far higher voter turnout rates, such as 9.8-12.8%. While most experiments have been conducted in the US, recent studies have found similar or somewhat smaller effects in Europe.

The guide to grassroots elections Get Out the Vote

determined that GOTV efforts averaged one vote every 15 door knocks by

volunteers ($31 dollars per vote), 35 phone calls by volunteers ($35

dollars per vote), or 273 pieces of nonpartisan direct mail ($91 dollars

per vote, no effect from partisan direct mail).

They note that campaigns which experiment carefully can do better than

these averages. Campaigns can raise turnout up to 8 percentage points

with direct mail which tells neighbors when other neighbors have voted

and promises to mail an update after the election, though people

complain when they have no way to opt in or out of notification.

Other studies have found that GOTV methods contribute little to

none to voter turnout. One field experiment found that GOTV phone calls

were largely ineffective, and that ease of access to polling locations

had the largest impact on voter turnout.

There is also the argument that GOTV targets a more affluent

demographic, which is already more likely to vote. Less politically

engaged demographic and socioeconomic groups are sometimes neglected in

GOTV efforts.

GOTV is often most effective when potential voters are told to do so "because others will ask."

Voters will then go to the polls as a means of fulfilling perceived

societal expectations. Paradoxically, informing voters that turnout is

expecting to be high was found to increase actual voter turnout, while

predicting lower turnouts actually resulted in less voters.

In 2004 Rock the Vote

paid to run TV ads aimed at young voters, on a random sample of small

cable systems where they could measure the effects. Turnout was three

percentage points higher among 18-19-year olds in these sample areas

than in the control group covered by other similar small cable systems;

there was less effect above age 22.

In November 2012 and 2013 Rock the Vote experimented with

Facebook ads to encourage voter turnout by telling people the number of

days remaining until the election and which of their friends "liked" the

countdown. The ads were shown to over 400,000 adults, randomly selected

from a base over 800,000. Rock the Vote had helped many of them

register. The ads did not increase turnout in the experimental group,

compared to the control group who did not get the ads.

In 2012 they also experimented with text message reminders to 180,000

people who had provided their mobile numbers. Texts the day before the

election raised turnout six tenths of a percentage point, while texts on

election day lowered turnout.

Several mobile apps

tell people where to vote, identify their elected officials, or search

candidates' positions, though no evidence measures how much these raise

turnout. Facebook apps let users see who their friends endorse, which gives them a shortcut in deciding whom to vote for.

Studies in 2012 and 2017 found that Facebook's “I’m Voting/I’m a

Voter” button increased turnout in the 2010 Congressional elections by

six tenths of a percentage point, and in the 2012 presidential election by a quarter of a percentage point.

It named their friends who had clicked the voting button, thus opting

in and minimizing complaints. However the button only appeared on

election day, so it did not let friends track and encourage each other

throughout the early voting period which most states have. It has been

used in many elections throughout the world since then, without clarity

on which users see it, leading to concerns on how it biases turnout.

Groups such as Postcards To Voters

send handwritten postcards to potential voters ahead of elections in

hopes of increasing turnout. A 2007 study showed that handwritten notes

were three times as effective as machine-printed ones.