The broadest historical trends in voter turnout in the United States presidential elections have been determined by the gradual expansion of voting rights

from the initial restriction to male property owners aged twenty-one or

older in the early years of the country's independence, to all citizens

aged eighteen or older in the mid-twentieth century. Voter turnout in

the presidential elections has historically been better than the turnout

for midterm elections.

Age, education, and income

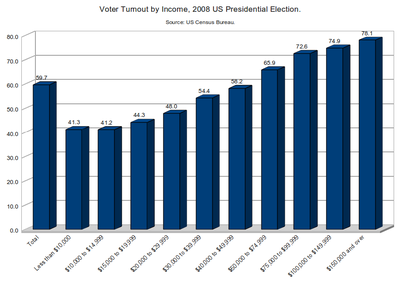

Rates of voting in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election by income

Rates in voting in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election by educational attainment

Age, income and educational attainment are significant factors

affecting voter turnout. Educational attainment is perhaps the best

predictor of voter turnout, and in the 2008 election those holding

advanced degrees were three times more likely to vote than those with

less than high school education. Income correlated well with likelihood

of voting as well, although this may be because of a correlation between

income and educational attainment, rather than a direct effect of

income.

Age difference is associated with youth voter turnout.

Berman and Johnson's (2000)

argument affirms that "age is an important factor in understanding

voting blocs and differences" on various issues. Young people are

typically "plagued" by political apathy and thus do not have strong

political opinions (The Economist, 2014). As strong political opinions

may be considered one of the reasons behind voting (Munsey, 2008),

political apathy among young people is arguably a predictor for low

voter turnout. Pomante and Schraufnagel's (2014) research demonstrated

that potential young voters are more willing to commit to vote when they

see pictures of younger candidates running for elections/office or

voting for other candidates, surmising that young Americans are "voting

at higher and similar rates to other Americans when there is a candidate

under the age of 35 years running". As such, since most candidates

running for office are pervasively over the age of 35 years (Struyk,

2017), youth may not be actively voting in these elections because of a

lack of representation or visibility in the political process. "Only 30

per cent of millennials think it's 'essential' to live in a democracy,

compared to 72 percent of those born before World War II" (Gershman,

2018). Considering that one of the critical tenets of liberal democracy

is voting, the idea that millennials are denouncing the value of

democracy is arguably an indicator of the loss of faith in the

importance of voting. Thus, it can be surmised that those of younger

ages may not be inclined to vote during elections.

Education is another factor considered to have a major impact on voter turnout rates.

Burden (2009) investigated the relationship between formal education

levels and voter turnout. He demonstrated the effect of rising

enrollment in college education circa 1980s, which – as expected - did

result in an increase in voter turnout. However, "this was not true for

political knowledge" (Burden, 2009); a rise in education levels did not

have any impact in identifying those with political knowledge (a

signifier of civic engagement) until the 1980s election, when college

education became a distinguishing factor in identifying civic

participation. This article poses a multifaceted perspective on the

effect of education levels on voter turnout. Based on this article, one

may surmise that education has become a more powerful predictor of civic

participation, discriminating more between voters and non-voters.

However, this was not true for political knowledge; education levels

were not a signifier of political knowledge. Gallego (2010) also

contends that voter turnout tends to be higher in localities where

voting mechanisms have been established and are easy to operate – i.e.

voter turnout and participation tends to be high in instances where

registration has been initiated by the state and the number of electoral

parties is small. One may contend that ease of access – and not

education level – may be an indicator of voting behavior. Presumably

larger, more urban cities will have greater

budgets/resources/infrastructure dedicated to elections, which is why

youth may have higher turnout rates in those cities versus more rural

areas. Though youth in larger (read: urban) cities tend to be more

educated than those in rural areas (Marcus & Krupnick, 2017),

perhaps there is an external variable (i.e. election infrastructure) at

play. Smith and Tolbert's (2005) research reiterates that the presence

of ballot initiatives and portals within a state have a positive effect

on voter turnout.

Another correlated finding in his study (Snyder, 2011) was that

education is less important as a predictor of voter turnout in states

than tend to spend more on education. Moreover, Snyder's (2011) research

suggests that students are more likely to vote than non-students. It

may be surmised that an increase of state investment in electoral

infrastructure facilitates and education policy and programs results in

increase voter turnout among youth.

Wealthier people tend to vote at higher rates.

Harder and Krosnick (2008) contend that some of the reasons for this may

be due to "differences in motivation or ability (sometimes both)"

(Harder and Krosnick, 2008), or that less wealthy people have less

energy, time, or resources to allot towards voting. Another potential

reason may be that wealthier people believe that they have more at stake

if they don't vote than those with less resources or income.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs might also help explain this hypothesis from

a psychological perspective. If those with low income are struggling to

meet the basic survival needs of food, water, safety, etc., they will

not be motivated enough to reach the final stages of "Esteem" or

"Self-actualization" needs (Maslow, 1943) – which consist of the desire

for dignity, respect, prestige and realizing personal potential,

respectively.

Women's suffrage and gender gap

There

was no systematic collection of voter turnout data by gender at a

national level before 1964, but smaller local studies indicate a low

turnout among female voters in the years following Women's suffrage in the United States.

For example, a 1924 study of voting turnout in Chicago found that

"female Chicagoans were far less likely to have visited the polls on

Election Day than were men in both the 1920 presidential election (46%

vs. 75%) and the 1923 mayoral contest (35% vs. 63%)."

The study compared reasons given by male and female non-voters, and

found that female non-voters were more likely to cite general

indifference to politics and ignorance or timidity regarding elections

than male non-voters, and that female voters were less likely to cite

fear of loss of business or wages. Most significantly, however, 11% of

female non-voters in the survey cited a "Disbelief in woman's voting" as

the reason they did not vote.

The graph of voter turnout percentages shows a dramatic decline

in turnout over the first two decades of the twentieth century, ending

in 1920, when the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

granted women the right to vote across the United States. But in the

preceding decades, several states had passed laws supporting women's

suffrage. Women were granted the right to vote in Wyoming in 1869,

before the territory had become a full state in the union.

In 1889, when the Wyoming constitution was drafted in preparation for

statehood, it included women's suffrage. Thus Wyoming was also the first

full state to grant women the right to vote. In 1893, Colorado was the

first state to amend an existing constitution in order to grant women

the right to vote, and several other states followed, including Utah and

Idaho in 1896, Washington State in 1910, California in 1911, Oregon,

Kansas, and Arizona in 1912, Alaska and Illinois in 1913, Montana and

Nevada in 1914, New York in 1917; Michigan, South Dakota, and Oklahoma

in 1918. Each of these suffrage laws expanded the body of eligible

voters, and because women were less likely to vote than men, each of

these expansions created a decline in voter turnout rates, culminating

with the extremely low turnouts in the 1920 and 1924 elections after the

passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Voter turnout by sex and age for the 2008 US Presidential Election.

This voting gender gap

waned throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century, and in

recent decades has completely reversed, with a higher proportion of

women voting than men in each of the last nine presidential elections.

The Center for American Women and Politics summarizes how this trend

can be measured differently both in terms of proportion of voters to

non-voters, and in terms of the bulk number of votes cast.

"In every presidential election since 1980, the proportion of eligible female adults who voted has exceeded the proportion

of eligible male adults who voted [...]. In all presidential elections

prior to 1980, the voter turnout rate for women was lower than the rate

for men. The number of female voters has exceeded the number of male voters in every presidential election since 1964..."

This gender gap has been a determining factor in several recent

presidential elections, as women have been consistently about 15% more

likely to support the candidate of the Democratic Party than the

Republican candidate in each election since 1996.

Race, ethnicity, and voter turnout

Voter turnout in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election by race/ethnicity.

The passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

gave African American men the right to vote. While this historic

expansion of rights resulted in significant increases in the eligible

voting population, and may have contributed to the increases in the

proportion of votes cast for president as a percentage of the total

population during the 1870s, there does not seem to have been a

significant long-term increase in the percentage of eligible voters who

turn out for the poll. The disenfranchisement of most African Americans and many poor whites

in the South during the years 1890-1910 likely contributed to the

decline in overall voter turnout percentages during those years visible

in the chart at the top of the article. Ethnicity has had an effect on

voter turnout in recent years as well, with data from recent elections

such as 2008 showing much lower turnout among people identifying as

Hispanic or Asian ethnicity than other voters.

Youth voting turnout

Recent

decades have seen increasing concern over the fact that youth voting

turnout is consistently lower than turnout among older generations.

Several programs to increase the rates of voting among young people—such

as MTV's "Rock the Vote" (founded in 1990) and the "Vote or Die"

initiative (starting in 2004)—may have marginally increased turnouts of

those between the ages of 18 and 25 to vote. However, the Stanford Social Innovation Review

found no evidence of a decline in youth voter turnout. In fact, they

argue that "Millennials are turning out at similar rates to the previous

two generations when they face their first elections."

Other eligibility factors

Another

factor influencing statistics on voter turnout is the percentage of the

country's voting-age population who are ineligible to vote due to

non-citizen status or prior felony convictions. In a 2001 article in the

American Political Science Review,

Michael McDonald and Samuel Popkin argued, that at least in the United

States, voter turnout since 1972 has not actually declined when

calculated for those eligible to vote, what they term the

voting-eligible population.

In 1972, noncitizens and ineligible felons (depending on state law)

constituted about 2% of the voting-age population. By 2004, ineligible

voters constituted nearly 10%.

Ineligible voters are not evenly distributed across the country – 20%

of California's voting-age population is ineligible to vote – which

confounds comparisons of states.

Turnout statistics

U.S. presidential election popular vote totals as a percentage of the total U.S. population. Note the surge in 1828 (extension of suffrage to non-property-owning white men), the drop from 1890–1910 (when Southern states disenfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites), and another surge in 1920 (extension of suffrage to women).

Note also that this chart represents the number of votes cast as a

percentage of total population, and does not compare either of those

quantities with the percentage of the population that was eligible to

vote.

| Election | Voting Age Population (VAP) | Turnout | % Turnout of VAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1789 |

| ||

| 1792 |

| ||

| 1796 |

| ||

| 1800 |

| ||

| 1804 |

| ||

| 1808 |

| ||

| 1812 |

| ||

| 1816 |

| ||

| 1820 |

| ||

| 1824 |

| ||

| 1828 | 57.6% | ||

| 1832 | 55.4% | ||

| 1836 | 57.8% | ||

| 1840 | 80.2% | ||

| 1844 | 78.9% | ||

| 1848 | 72.7% | ||

| 1852 | 69.6% | ||

| 1856 | 78.9% | ||

| 1860 | 81.2% | ||

| 1864 | 73.8% | ||

| 1868 | 78.1% | ||

| 1872 | 71.3% | ||

| 1876 | 81.8% | ||

| 1880 | 79.4% | ||

| 1884 | 77.5% | ||

| 1888 | 79.3% | ||

| 1892 | 74.7% | ||

| 1896 | 79.3% | ||

| 1900 | 73.2% | ||

| 1904 | 65.2% | ||

| 1908 | 65.4% | ||

| 1912 | 58.8% | ||

| 1916 | 61.6% | ||

| 1920 | 49.2% | ||

| 1924 | 48.9% | ||

| 1928 | 56.9% | ||

| 1932 | 75,768,000 | 39,817,000 | 52.6% |

| 1936 | 80,174,000 | 45,647,000 | 56.9% |

| 1940 | 84,728,000 | 49,815,000 | 58.8% |

| 1944 | 85,654,000 | 48,026,000 | 56.1% |

| 1948 | 95,573,000 | 48,834,000 | 51.1% |

| 1952 | 99,929,000 | 61,552,000 | 61.6% |

| 1956 | 104,515,000 | 62,027,000 | 59.3% |

| 1960 | 109,672,000 | 68,836,000 | 62.8% |

| 1964 | 114,090,000 | 70,098,000 | 61.4% |

| 1968 | 120,285,000 | 73,027,000 | 60.7% |

| 1972 | 140,777,000 | 77,625,000 | 55.1% |

| 1976 | 152,308,000 | 81,603,000 | 53.6% |

| 1980 | 163,945,000 | 86,497,000 | 52.8% |

| 1984 | 173,995,000 | 92,655,000 | 53.3% |

| 1988 | 181,956,000 | 91,587,000 | 50.3% |

| 1992 | 189,493,000 | 104,600,000 | 55.2% |

| 1996 | 196,789,000 | 96,390,000 | 49.0% |

| 2000 | 209,787,000 | 105,594,000 | 50.3% |

| 2004 | 219,553,000 | 122,349,000 | 55.7% |

| 2008 | 229,945,000 | 131,407,000 | 58.2% |

| 2012 | 235,248,000 | 129,235,000 | 54.9% |

| 2016 | 250,056,000 | 138,847,000 | 55.7% |

Note: The Bipartisan Policy Center

has stated that turnout for 2012 was 57.5 percent of the eligible

voters, which they claim was a decline from 2008. They estimate that as a

percent of eligible voters, turn out was: 2000, 54.2%; in 2004 60.4%;

2008 62.3%; and 2012 57.5%.

Later analysis by the University of California, Santa Barbara's American Presidency Project found that there were 235,248,000 people of voting age in the United States in the 2012 election, resulting in 2012 voting age population (VAP) turnout of 54.9%.

The total increase in VAP between 2008 and 2012 (5,300,000) was the

smallest increase since 1964, bucking the modern average of

8,000,000–13,000,000 per cycle.