Voters lining up outside a Baghdad polling station during the 2005 Iraqi election. Voter turnout was considered high despite widespread concerns of violence.

Voter turnout is the percentage of eligible voters who cast a ballot in an election.

Eligibility varies by country, and the voting-eligible population

should not be confused with the total adult population. Age and

citizenship status are often among the criteria used to determine

eligibility, but some countries further restrict eligibility based on

sex, race, or religion.

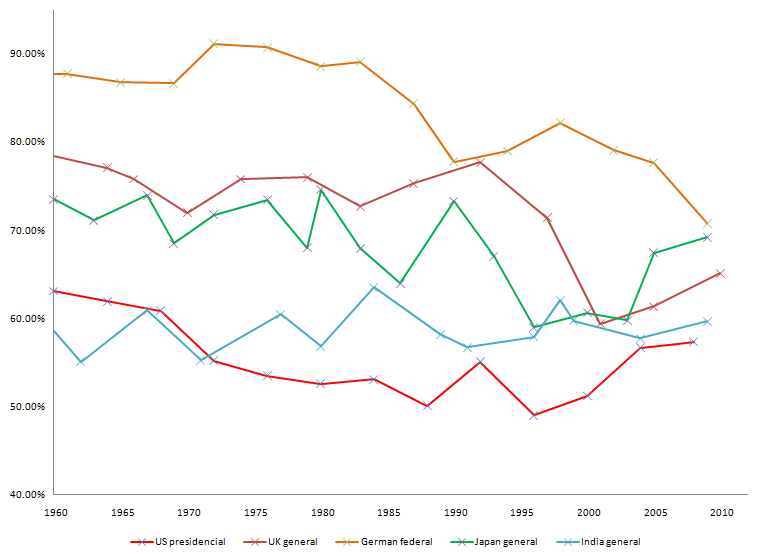

After increasing for many decades, there has been a trend of decreasing voter turnout in most established democracies since the 1980s. In general, low turnout is attributed to disillusionment, indifference,

or a sense of futility (the perception that one's vote won't make any

difference). According to Stanford University political scientists Adam

Bonica and Michael McFaul, there is a consensus among political

scientists that "democracies perform better when more people vote."

Low turnout is usually considered to be undesirable. As a result,

there have been many efforts to increase voter turnout and encourage

participation in the political process. In spite of significant study

into the issue, scholars are divided on the reasons for the decline. Its

cause has been attributed to a wide array of economic, demographic, cultural, technological, and institutional factors.

Different countries have very different voter turnout rates. For example, turnout in the United States 2012 presidential election was about 55%. In both Belgium, which has obligatory attendance, and Malta, which does not, participation reaches about 95%. In Belgium there is obligatory attendance which is often misinterpreted as compulsory voting.

Reasons for voting

The chance of any one vote determining the outcome is low. Some studies show that a single vote in a voting scheme such as the Electoral College in the United States has an even lower chance of determining the outcome. Other studies claim that the Electoral College actually increases voting power. Studies using game theory, which takes into account the ability of voters to interact, have also found that the expected turnout for any large election should be zero.

The basic formula for determining whether someone will vote, on

the questionable assumption that people act completely rationally, is

where

- P is the probability that an individual's vote will affect the outcome of an election,

- B is the perceived benefit that would be received if that person's favored political party or candidate were elected,

- D originally stood for democracy or civic duty, but today represents any social or personal gratification an individual gets from voting, and

- C is the time, effort, and financial cost involved in voting.

Since P is virtually zero in most elections, PB is also near zero, and D is thus the most important element in motivating people to vote. For a person to vote, these factors must outweigh C. Experimental political science has found that even when P

is likely greater than zero, this term has no effect on voter turnout.

Enos and Fowler (2014) conducted a field experiment that exploits the

rare opportunity of a tied election for major political office.

Informing citizens that the special election to break the tie will be

close (meaning a high P term) has little mobilizing effect on voter turnout.

Riker and Ordeshook developed the modern understanding of D.

They listed five major forms of gratification that people receive for

voting: complying with the social obligation to vote; affirming one's

allegiance to the political system; affirming a partisan preference

(also known as expressive voting, or voting for a candidate to express

support, not to achieve any outcome); affirming one's importance to the

political system; and, for those who find politics interesting and

entertaining, researching and making a decision. Other political scientists have since added other motivators and questioned some of Riker and Ordeshook's assumptions. All of these concepts are inherently imprecise, making it difficult to discover exactly why people choose to vote.

Recently, several scholars have considered the possibility that B

includes not only a personal interest in the outcome, but also a

concern for the welfare of others in the society (or at least other

members of one's favorite group or party). In particular, experiments in which subject altruism was measured using a dictator game showed that concern for the well-being of others is a major factor in predicting turnout and political participation. Note that this motivation is distinct from D, because voters must think others benefit from the outcome of the election, not their act of voting in and of itself.

Reasons for not voting

There are philosophical, moral, and practical reasons that some

people cite for not voting in electoral politics. Researchers have also

identified several strategic motivations for abstention in which a voter

is better off by not voting. The most straightforward example of this

is known as the No-Show Paradox, which can occur in both large and small

electorates.

Significance

High

voter turnout is often considered to be desirable, though among

political scientists and economists specializing in public choice, the

issue is still debated. A high turnout is generally seen as evidence of the legitimacy of the current system. Dictators have often fabricated high turnouts in showcase elections for this purpose. For instance, Saddam Hussein's 2002 plebiscite was claimed to have had 100% participation.

Opposition parties sometimes boycott votes they feel are unfair or

illegitimate, or if the election is for a government that is considered

illegitimate. For example, the Holy See instructed Italian Catholics to boycott national elections for several decades after the creation of the state of Italy. In some countries, there are threats of violence against those who vote, such as during the 2005 Iraq elections, an example of voter suppression.

However, some political scientists question the view that high turnout

is an implicit endorsement of the system. Mark N. Franklin contends that

in European Union elections opponents of the federation, and of its legitimacy, are just as likely to vote as proponents.

Assuming that low turnout is a reflection of disenchantment or

indifference, a poll with very low turnout may not be an accurate

reflection of the will of the people.

On the other hand, if low turnout is a reflection of contentment of

voters about likely winners or parties, then low turnout is as

legitimate as high turnout, as long as the right to vote exists. Still,

low turnouts can lead to unequal representation among various parts of

the population. In developed countries, non-voters tend to be

concentrated in particular demographic and socioeconomic groups,

especially the young and the poor. However, in India,

which boasts an electorate of more than 814 million people, the

opposite is true. The poor, who comprise the majority of the

demographic, are more likely to vote than the rich and the middle

classes, and turnout is higher in rural areas than urban areas. In low-turnout countries, these groups are often significantly under-represented in elections. This has the potential to skew policy. For instance, a high voter turnout among the elderly coupled with a low turnout among the young may lead to more money for retirees' health care,

and less for youth employment schemes. Some nations thus have rules

that render an election invalid if too few people vote, such as Serbia, where three successive presidential elections were rendered invalid in 2003.

Determinants and demographics of turnout

| USA (1988) | India (1988) |

|---|---|

| Turnout | |

| 50.1 % | 62 % |

| Income (Quinitile) | |

| Lowest 20%: 36.4% | 57 % |

| 52 | 65 |

| 59 | 73 |

| 67 | 60 |

| Highest 20%: 63.1 | 47 |

| Education | |

| No high school 38% | Illiterate 57% |

| Some high school 43 | Up to middle 83 |

| High school graduate 57 | College 57 |

| Some college 66 | Post-graduate 41 |

| College grad 79 |

|

| Post-graduate 84 |

|

| Community (1996) | |

| White 56 | Hindu 60 |

| Black 50 | Hindu (OBC) 58 |

| Latino 27 | SC 75 |

|

|

ST 59 |

|

|

Muslim 70 |

|

|

Sikh 89 |

In each country, some parts of society are more likely to vote than

others. In high-turnout countries, these differences tend to be limited.

As turnout approaches 90%, it becomes difficult to find significant

differences between voters and nonvoters, but in low turnout nations the

differences between voters and non-voters can be quite marked.

Habit

Turnout

differences appear to persist over time; in fact, the strongest

predictor of individual turnout is whether or not one voted in the

previous election.

As a result, many scholars think of turnout as habitual behavior that

can be learned or unlearned, especially among young adults.

Childhood influences

One study found that improving children's social skills increases their turnout as adults.

Demographics

Socioeconomic

factors are significantly associated with whether individuals develop

the habit of voting. The most important socioeconomic factor affecting

voter turnout is education.

The more educated a person is, the more likely they are to vote, even

controlling for other factors that are closely associated with education

level, such as income and class.

Income has some effect independently: wealthier people are more likely

to vote, regardless of their educational background. There is some

debate over the effects of ethnicity, race, and gender.

In the past, these factors unquestionably influenced turnout in many

nations, but nowadays the consensus among political scientists is that

these factors have little effect in Western democracies when education

and income differences are taken into account.

A 2018 study found that while education did not increase turnout on

average, it did raise turnout among individuals from low socioeconomic

status households.

However, since different ethnic groups typically have different

levels of education and income, there are important differences in

turnout between such groups in many societies. Other demographic factors

have an important influence: young people are far less likely to vote

than the elderly.[citation needed]

Occupation has little effect on turnout, with the notable exception of

higher voting rates among government employees in many countries.

There can also be regional differences in voter turnout. One

issue that arises in continent-spanning nations, such as Australia, Canada, the United States and Russia, is that of time zones.

Canada banned the broadcasting of election results in any region where

the polls have not yet closed; this ban was upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada.

In several recent Australian national elections, the citizens of

Western Australia knew which party would form the new government up to

an hour before the polling booths in their State closed.

Differences between elections

Within countries there can be important differences in turnout between individual elections. Elections where control of the national executive is not at stake generally have much lower turnouts—often half that for general elections.

Municipal and provincial elections, and by-elections to fill casual

vacancies, typically have lower turnouts, as do elections for the

parliament of the supranational European Union, which is separate from the executive branch of the EU's government. In the United States, midterm congressional elections attract far lower turnouts than Congressional elections held concurrently with Presidential ones. Runoff elections also tend to attract lower turnouts.

Competitiveness of races

In

theory, one of the factors that is most likely to increase turnout is a

close race. With an intensely polarized electorate and all polls

showing a close finish between President George W. Bush and Democratic challenger John F. Kerry, the turnout in the 2004 U.S. presidential election

was close to 60%, resulting in a record number of popular votes for

both candidates (around 62 million for Bush and 59 million for Kerry).

However, this race also demonstrates the influence that contentious

social issues can have on voter turnout; for example, the voter turnout

rate in 1860 wherein anti-slavery

candidate Abraham Lincoln won the election was the second-highest on

record (81.2 percent, second only to 1876, with 81.8 percent).

Nonetheless, there is evidence to support the argument that predictable

election results—where one vote is not seen to be able to make a

difference—have resulted in lower turnouts, such as Bill Clinton's 1996 re-election (which featured the lowest voter turnout in the United States since 1924), the United Kingdom general election of 2001, and the 2005 Spanish referendum on the European Constitution; all of these elections produced decisive results on a low turnout.

A 2017 NBER paper found that an awareness by the electorate that

an election would be close increased turnout: "Closer elections are

associated with greater turnout only when polls exist. Examining

within-election variation in newspaper reporting on polls across

cantons, we find that close polls increase turnout significantly more

where newspapers report on them most."

Incarceration

One 2017 study in the Journal of Politics

found that, in the United States, incarceration had no significant

impact on turnout in elections: ex-felons did not become less likely to

vote after their time in prison. Also in the United States, incarceration, probation, and a felony record

deny 5–6 million Americans of the right to vote, with reforms gradually

leading more states to allow people with felony criminal records to

vote, while almost none allow incarcerated people to vote.

Access to polling places

A

2017 study found that the opening and closing hours of polling places

determines the age demographics of turnout: turnout among younger voters

is higher the longer polling places are open and turnout among older

voters decreases the later polling places open.

Costs of participation

A 2017 study in Electoral Studies

found that Swiss cantons that reduced the costs of postal voting for

voters by prepaying the postage on return envelopes (which otherwise

cost 85 Swiss Franc cents) were "associated with a statistically

significant 1.8 percentage point increase in voter turnout". A 2016 study in the American Journal of Political Science

found that preregistration - allowing young citizens to register before

being eligible to vote - increased turnout by 2 to 8 percentage points. A 2019 study in Social Science Quarterly found that the introduction of a vote‐by‐mail system in Washington state led to an increase in turnout. Another 2019 study in Social Science Quarterly found that online voter registration increased voter turnout, in particular for young voters.

A 2018 study in the British Journal of Political Science

found that internet voting in local elections in Ontario, Canada, only

had a modest impact on turnout, increasing turnout by 3.5 percentage

points. The authors of the study say that the results "suggest that

internet voting is unlikely to solve the low turnout crisis, and imply

that cost arguments do not fully account for recent turnout declines."

According to an article by Emily Badger in "The New York Times",

there is research that explores how the turnout of the 2016 presidential

election would have changed if the voter turnout had been different.

Badger writes ““If everybody voted, Clinton wins. If minority turnout

was equal to white turnout, Clinton wins,” said Mr. Fraga, who describes

these patterns in a new book, “The Turnout Gap.” Many white voters who

preferred Mr. Trump sat out 2016 as well. So, in this full-turnout

counterfactual, Mrs. Clinton doesn't overcome Mr. Trump's narrow

victories in Wisconsin, Michigan or Pennsylvania. Rather, she flips

Florida, North Carolina and Texas. The preferences of the population are

aligned with a Democratic majority in the Senate as well, Mr. Fraga

says, despite the bias toward rural states. We don't see that, he

argues, because of disparities in turnout.” (Badger, 2018:P. 12-13).

Knowledge

A

2017 experimental study found that by sending registered voters between

the ages of 18 and 30 a voter guide containing salient information about

candidates in an upcoming election (a list of candidate endorsements

and the candidates' policy positions on five issues in the campaign)

increased turnout by 0.9 points.

Weather

Research results are mixed as to whether bad weather affects turnout. There is research that shows that precipitation

can reduce turnout, though this effect is generally rather small, with

most studies finding each millimeter of rainfall to reduce turnout by

0.015 to 0.1 percentage points. At least two studies, however, found no evidence that weather disruptions reduce turnout. A 2011 study found "that while rain decreases turnout on average, it does not do so in competitive elections."

Some research has also investigated the effect of temperature on

turnout, with some finding increased temperatures to moderately increase

turnout. Some other studies, however, found temperature to have no significant impact on turnout. These variations in turnout can also have partisan impacts; a 2017 study in the journal American Politics Research

found that rainfall increased Republican vote shares, because it

decreased turnout more among Democratic voters than Republican voters. Studies from the Netherlands and Germany have also found weather-related turnout decreases to benefit the right, while a Spanish study found a reverse relationship.

The season and the day of the week (although many nations hold

all their elections on the same weekday) can also affect turnout.

Weekend and summer elections find more of the population on holiday or

uninterested in politics, and have lower turnouts. When nations set

fixed election dates, these are usually midweek during the spring or

autumn to maximize turnout. Variations in turnout between elections tend

to be insignificant. It is extremely rare for factors such as

competitiveness, weather, and time of year to cause an increase or

decrease in turnout of more than five percentage points, far smaller

than the differences between groups within society, and far smaller than

turnout differentials between nations.

Hereditary factors

Limited

research suggests that genetic factors may also be important. Some

scholars recently argued that the decision to vote in the United States

has very strong heritability, using twin studies of validated turnout in Los Angeles and self-reported turnout in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health to establish that.

They suggest that genetics could help to explain why parental turnout

is such a strong predictor of voting in young people, and also why

voting appears to be habitual.

Further, they suggest, if there is an innate predisposition to vote or

abstain, this would explain why past voting behavior is such a good

predictor of future voter reaction.

In addition to the twin study

method, scholars have used gene association studies to analyze voter

turnout. Two genes that influence social behavior have been directly

associated with voter turnout, specifically those regulating the serotonin system in the brain via the production of monoamine oxidase and 5HTT.

However, this study was reanalyzed by separate researchers who

concluded these "two genes do not predict voter turnout", pointing to

several significant errors, as well as "a number of difficulties, both

methodological and genetic" in studies in this field. Once these errors

were corrected, there was no longer any statistically significant

association between common variants of these two genes and voter

turnout.

Household socialization

A 2018 study in the American Political Science Review found that the parents to newly enfranchised voters "become 2.8 percentage points more likely to vote." A 2018 study in the journal Political Behavior found that increasing the size of households increases a household member's propensity to vote.

A 2018 PlosOne study found that a "partisan who is married to a

co-partisan is more likely to vote. This phenomenon is especially

pronounced for partisans in closed primaries, elections in which

non-partisan registered spouses are ineligible to participate."

Enfranchisement

A 2018 study in The Journal of Politics

found that Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act "increased black

voter registration by 14–19 percentage points, white registration by

10–13 percentage points, and overall voter turnout by 10–19 percentage

points. Additional results for Democratic vote share suggest that some

of this overall increase in turnout may have come from reactionary

whites."

Ballot secrecy

According

to a 2018 study, get-out-the-vote groups in the United States who

emphasize ballot secrecy along with reminders to vote increase turnout

by about 1 percentage point among recently registered nonvoters.

International differences

Voter

turnout varies considerably between nations. It tends to be lower in

the United States, Asia and Latin America than in most of Europe, Canada and Oceania. Western Europe averages a 77% turnout, and South and Central America around 54% since 1945.

The differences between nations tend to be greater than those between

classes, ethnic groups, or regions within nations. Confusingly, some of

the factors that cause internal differences do not seem to apply on a

global level. For instance, nations with better-educated populaces do

not have higher turnouts.

There are two main commonly cited causes of these international

differences: culture and institutions. However, there is much debate

over the relative impact of the various factors.

Cultural factors

Wealth and literacy have some effect on turnout, but are not reliable measures. Countries such as Angola and Ethiopia have long had high turnouts, but so have the wealthy states of Europe. The United Nations Human Development Index

shows some correlation between higher standards of living and higher

turnout. The age of a democracy is also an important factor. Elections

require considerable involvement by the population, and it takes some

time to develop the cultural habit of voting, and the associated

understanding of and confidence in the electoral process. This factor

may explain the lower turnouts in the newer democracies of Eastern

Europe and Latin America. Much of the impetus to vote comes from a sense

of civic duty, which takes time and certain social conditions that can

take decades to develop:

- trust in government;

- degree of partisanship among the population;

- interest in politics, and

- belief in the efficacy of voting.

Demographics also have an effect. Older people tend to vote more than

youths, so societies where the average age is somewhat higher, such as

Europe; have higher turnouts than somewhat younger countries such as the

United States. Populations that are more mobile and those that have

lower marriage rates tend to have lower turnout. In countries that are

highly multicultural and multilingual, it can be difficult for national

election campaigns to engage all sectors of the population.

The nature of elections also varies between nations. In the United States, negative campaigning and character attacks are more common than elsewhere, potentially suppressing turnouts. The focus placed on get out the vote

efforts and mass-marketing can have important effects on turnout.

Partisanship is an important impetus to turnout, with the highly

partisan more likely to vote. Turnout tends to be higher in nations

where political allegiance is closely linked to class, ethnic,

linguistic, or religious loyalties. Countries where multiparty systems have developed also tend to have higher turnouts. Nations with a party specifically geared towards the working class will tend to have higher turnouts among that class than in countries where voters have only big tent parties, which try to appeal to all the voters, to choose from.

A four-wave panel study conducted during the 2010 Swedish national

election campaign, show (1) clear differences in media use between age

groups and (2) that both political social media use and attention to

political news in traditional media increase political engagement over

time.

Institutional factors

Institutional

factors have a significant impact on voter turnout. Rules and laws are

also generally easier to change than attitudes, so much of the work done

on how to improve voter turnout looks at these factors. Making voting compulsory has a direct and dramatic effect on turnout. Simply making it easier for candidates to stand through easier nomination rules is believed to increase voting. Conversely, adding barriers, such as a separate registration

process, can suppress turnout. The salience of an election, the effect

that a vote will have on policy, and its proportionality, how closely

the result reflects the will of the people, are two structural factors

that also likely have important effects on turnout.

Voter registration

The

modalities of how electoral registration is conducted can also affect

turnout. For example, until "rolling registration" was introduced in the

United Kingdom, there was no possibility of the electoral register

being updated during its currency, or even amending genuine mistakes

after a certain cut off date. The register was compiled in October, and

would come into force the next February, and would remain valid until

the next January. The electoral register would become progressively more

out of date during its period of validity, as electors moved or died

(also people studying or working away from home often had difficulty

voting). This meant that elections taking place later in the year tended

to have lower turnouts than those earlier in the year. The introduction

of rolling registration where the register is updated monthly has

reduced but not entirely eliminated this issue since the process of

amending the register is not automatic, and some individuals do not join

the electoral register until the annual October compilation process.

In comparison, the introduction of individual electoral registration in

the UK was thought to have negatively affected the number of eligible

citizens on the register and voter turnout.

Another country with a highly efficient registration process is

France. At the age of eighteen, all youth are automatically registered.

Only new residents and citizens who have moved are responsible for

bearing the costs and inconvenience of updating their registration.

Similarly, in Nordic countries,

all citizens and residents are included in the official population

register, which is simultaneously a tax list, voter registration, and

membership in the universal health system. Residents are required by law

to report any change of address to register within a short time after

moving. This is also the system in Germany (but without the membership in the health system).

The elimination of registration as a separate bureaucratic step

can result in higher voter turnout. This is reflected in statistics from

the United States Bureau of Census, 1982–1983. States that have same

day registration, or no registration requirements, have a higher voter

turnout than the national average. At the time of that report, the four

states that allowed election day registration were Minnesota, Wisconsin,

Maine, and Oregon. Since then, Idaho and Maine have changed to allow

same day registration. North Dakota is the only state that requires no

registration.

Compulsory voting

One of the strongest factors affecting voter turnout is whether voting is compulsory. In Australia, voter registration and attendance at a polling booth have been mandatory since the 1920s, with the most recent federal election in 2016 having turnout figures of 91% for the House of Representatives and 91.9% for the Senate. Several other countries have similar laws, generally with somewhat reduced levels of enforcement. If a Bolivian voter fails to participate in an election, the citizen may be denied withdrawal of their salary from the bank for three months.

In Mexico and Brazil,

existing sanctions for non-voting are minimal or are rarely enforced.

When enforced, compulsion has a dramatic effect on turnout.

In Venezuela and the Netherlands compulsory voting has been rescinded, resulting in substantial decreases in turnout.

In Greece voting is compulsory, however there are practically no sanctions for those who do not vote.

In Luxembourg

voting is compulsory, too, but not strongly enforced. In Luxembourg

only voters below the age of 75 and those who are not physically

handicapped or chronically ill have the legal obligation to vote.

In Belgium attendance is required and absence is punishable by law.

Sanctions for non-voting behaviour were foreseen sometimes even in absence of a formal requirement

to vote. In Italy

the Constitution describes voting as a duty (art. 48), though electoral

participation is not obligatory. From 1946 to 1992, thus, the Italian

electoral law included light sanctions for non-voters (lists of

non-voters were posted at polling stations).

Turnout rates have not declined substantially since 1992 in Italy,

though, pointing to other factors than compulsory voting to explain high

electoral participation.

Salience

Mark

N. Franklin argues that salience, the perceived effect that an

individual vote will have on how the country is run, has a significant

effect on turnout. He presents Switzerland

as an example of a nation with low salience. The nation's

administration is highly decentralized, so that the federal government

has limited powers. The government invariably consists of a coalition of

parties, and the power wielded by a party is far more closely linked to

its position relative to the coalition than to the number of votes it

received. Important decisions are placed before the population in a referendum.

Individual votes for the federal legislature are thus unlikely to have a

significant effect on the nation, which probably explains the low

average turnouts in that country. By contrast Malta,

with one of the world's highest voter turnouts, has a single

legislature that holds a near monopoly on political power. Malta has a two-party system in which a small swing in votes can completely alter the executive.

On the other hand, countries with a two-party system can experience low

turnout if large numbers of potential voters perceive little real

difference between the main parties. Voters' perceptions of fairness

also have an important effect on salience. If voters feel that the

result of an election is more likely to be determined by fraud and

corruption than by the will of the people, fewer people will vote.

Proportionality

Another

institutional factor that may have an important effect is

proportionality, i.e., how closely the legislature reflects the views of

the populace. Under a pure proportional representation

system the composition of the legislature is fully proportional to the

votes of the populace and a voter can be sure that of being represented

in parliament, even if only from the opposition benches. (However many

nations that use a form of proportional representation in elections

depart from pure proportionality by stipulating that smaller parties are

not supported by a certain threshold percentage of votes cast will be

excluded from parliament.) By contrast, a voting system based on single

seat constituencies (such as the plurality system

used in North America, the UK and India) will tend to result in many

non-competitive electoral districts, in which the outcome is seen by

voters as a foregone conclusion.

Proportional systems tend to produce multiparty coalition governments. This may reduce salience, if voters perceive that they have little influence over which parties are included in the coalition. For instance, after the 2005 German election,

the creation of the executive not only expressed the will of the voters

of the majority party but also was the result of political deal-making.

Although there is no guarantee, this is lessened as the parties usually

state with whom they will favour a coalition after the elections.

Political scientists are divided on whether proportional

representation increases voter turnout, though in countries with

proportional representation voter turnout is higher. There are other systems that attempt to preserve both salience and proportionality, for example, the Mixed member proportional representation system in New Zealand

(in operation since 1996), Germany, and several other countries.

However, these tend to be complex electoral systems, and in some cases

complexity appears to suppress voter turnout. The dual system in Germany, though, seems to have had no negative impact on voter turnout.

Ease of voting

Ease

of voting is a factor in rates of turnout. In the United States and

most Latin American nations, voters must go through separate voter registration

procedures before they are allowed to vote. This two-step process quite

clearly decreases turnout. U.S. states with no, or easier, registration

requirements have larger turnouts. Other methods of improving turnout include making voting easier through more available absentee polling

and improved access to polls, such as increasing the number of possible

voting locations, lowering the average time voters have to spend

waiting in line, or requiring companies to give workers some time off on

voting day. In some areas, generally those where some polling centres are relatively inaccessible, such as India, elections often take several days. Some countries have considered Internet voting as a possible solution. In other countries, like France,

voting is held on the weekend, when most voters are away from work.

Therefore, the need for time off from work as a factor in voter turnout

is greatly reduced.

Many countries have looked into Internet voting as a possible

solution for low voter turnout. Some countries like France and

Switzerland use Internet voting. However, it has only been used

sparingly by a few states in the US. This is due largely to security

concerns. For example, the US Department of Defense looked into making

Internet voting secure, but cancelled the effort.

The idea would be that voter turnout would increase because people

could cast their vote from the comfort of their own homes, although the

few experiments with Internet voting have produced mixed results.

Voter fatigue

Voter fatigue can lower turnout. If there are many elections in close

succession, voter turnout will decrease as the public tires of

participating. In low-turnout Switzerland, the average voter is invited

to go to the polls an average of seven times a year; the United States

has frequent elections, with two votes per year on average, if one

includes all levels of government as well as primaries.

Holding multiple elections at the same time can increase turnout;

however, presenting voters with massive multipage ballots, as occurs in

some parts of the United States, can reduce turnouts.

Voter pledges

A

2018 study found that "young people who pledge to vote are more likely

to turn out than those who are contacted using standard Get-Out-the-Vote

materials. Overall, pledging to vote increased voter turnout by 3.7

points among all subjects and 5.6 points for people who had never voted

before."

Measuring turnout

Differing

methods of measuring voter turnout can contribute to reported

differences between nations. There are difficulties in measuring both

the numerator, the number of voters who cast votes, and the denominator,

the number of voters eligible to vote.

For the numerator, it is often assumed that the number of voters

who went to the polls should equal the number of ballots cast, which in

turn should equal the number of votes counted, but this is not the case.

Not all voters who arrive at the polls necessarily cast ballots. Some

may be turned away because they are ineligible, some may be turned away

improperly, and some who sign the voting register may not actually cast

ballots. Furthermore, voters who do cast ballots may abstain,

deliberately voting for nobody, or they may spoil their votes, either accidentally or as an act of protest.

In the United Kingdom, the Electoral Commission distinguishes between "valid vote turnout", which excludes spoilt ballots, and "ballot box turnout", which does not.

In the United States, it has been common to report turnout as the

sum of votes for the top race on the ballot, because not all

jurisdictions report the actual number of people who went to the polls

nor the number of undervotes or overvotes.

Overvote rates of around 0.3 percent are typical of well-run elections,

but in Gadsden County Florida, the overvote rate was 11 percent in

November 2000.

For the denominator, it is often assumed that the number of

eligible voters was well defined, but again, this is not the case. In

the United States, for example, there is no accurate registry of exactly

who is eligible to vote, since only about 70–75% of people choose to

register themselves.

Thus, turnout has to be calculated based on population estimates. Some

political scientists have argued that these measures do not properly

account for the large number of Legal Permanent Residents, illegal aliens, disenfranchised felons

and persons who are considered 'mentally incompetent' in the United

States, and that American voter turnout is higher than is normally

reported.

Even in countries with fewer restrictions on the franchise, VAP turnout

can still be biased by large numbers of non-citizen residents, often

under-reporting turnout by as much as 10 percentage points. Professor Michael P. McDonald constructed an estimation of the turnout against the 'voting eligible population' (VEP), instead of the 'voting age population'

(VAP). For the American presidential elections of 2004, turnout could

then be expressed as 60.32% of VEP, rather than 55.27% of VAP.

In New Zealand, registration is supposed to be universal. This

does not eliminate uncertainty in the eligible population because this

system has been shown to be unreliable, with a large number of eligible

but unregistered citizens, creating inflated turnout figures.

A second problem with turnout measurements lies in the way

turnout is computed. One can count the number of voters, or one can

count the number of ballots, and in a vote-for-one race, one can sum the

number of votes for each candidate. These are not necessarily

identical because not all voters who sign in at the polls necessarily

cast ballots, although they ought to, and because voters may cast spoiled ballots.

Trends of decreasing turnout since the 1980s

Over the last 40 years, voter turnout has been steadily declining in the established democracies.

This trend has been significant in the United States, Western Europe,

Japan and Latin America. It has been a matter of concern and controversy

among political scientists for several decades. During this same

period, other forms of political participation have also declined, such

as voluntary participation in political parties and the attendance of

observers at town meetings. The decline in voting has also accompanied a

general decline in civic participation, such as church attendance,

membership in professional, fraternal, and student societies, youth

groups, and parent-teacher associations. At the same time, some forms of participation have increased. People have become far more likely to participate in boycotts, demonstrations, and to donate to political campaigns.

Before the late 20th century, suffrage

— the right to vote — was so limited in most nations that turnout

figures have little relevance to today. One exception was the United

States, which had near universal white male suffrage by 1840. The U.S.

saw a steady rise in voter turnout during the century, reaching its peak

in the years after the Civil War. Turnout declined from the 1890s until the 1930s, then increased again until 1960 before beginning its current long decline.

In Europe, voter turnouts steadily increased from the introduction of

universal suffrage before peaking in the mid-to-late 1960s, with modest

declines since then. These declines have been smaller than those in the

United States, and in some European countries turnouts have remained

stable and even slightly increased. Globally, voter turnout has

decreased by about five percentage points over the last four decades.

Reasons for decline

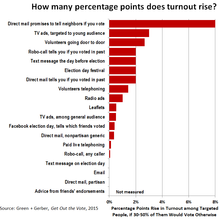

Methods of raising turnout.

Many causes have been proposed for this decline; a combination of

factors is most likely. When asked why they do not vote, many people

report that they have too little free time. However, over the last

several decades, studies have consistently shown that the amount of leisure time

has not decreased. According to a study by the Heritage Foundation,

Americans report on average an additional 7.9 hours of leisure time per

week since 1965.

Furthermore, according to a study by the National Bureau of Economic

Research, increases in wages and employment actually decrease voter

turnout in gubernatorial elections and do not affect national races.

Potential voters' perception that they are busier is common and might

be just as important as a real decrease in leisure time. Geographic

mobility has increased over the last few decades. There are often

barriers to voting in a district where one is a recent arrival, and a

new arrival is likely to know little about the local candidate and local

issues. Francis Fukuyama has blamed the welfare state,

arguing that the decrease in turnout has come shortly after the

government became far more involved in people's lives. He argues in Trust: The Social Virtues and The Creation of Prosperity that the social capital

essential to high voter turnouts is easily dissipated by government

actions. However, on an international level those states with the most

extensive social programs tend to be the ones with the highest turnouts.

Richard Sclove argues in Democracy and Technology that

technological developments in society such as "automobilization,"

suburban living, and "an explosive proliferation of home entertainment

devices" have contributed to a loss of community, which in turn has

weakened participation in civic life.

Trust in government and in politicians has decreased in many

nations. However, the first signs of decreasing voter turnout occurred

in the early 1960s, which was before the major upheavals of the late

1960s and 1970s. Robert D. Putnam

argues that the collapse in civil engagement is due to the introduction

of television. In the 1950s and 1960s, television quickly became the

main leisure activity in developed nations. It replaced earlier more

social entertainments such as bridge clubs, church groups, and bowling

leagues. Putnam argues that as people retreated within their homes and

general social participation declined, so too did voting.

Rosenstone and Hansen contend that the decline in turnout in the

United States is the product of a change in campaigning strategies as a

result of the so-called new media. Before the introduction of

television, almost all of a party's resources would be directed towards

intensive local campaigning and get out the vote

initiatives. In the modern era, these resources have been redirected to

expensive media campaigns in which the potential voter is a passive

participant. During the same period, negative campaigning has become ubiquitous in the United States and elsewhere and has been shown to impact voter turnout. Attack ads

and smear campaigns give voters a negative impression of the entire

political process. The evidence for this is mixed: elections involving

highly unpopular incumbents generally have high turnout; some studies

have found that mudslinging and character attacks reduce turnout, but

that substantive attacks on a party's record can increase it.

Part of the reason for voter decline in the recent 2016 election

is likely because of restrictive voting laws around the country. Brennan

Center for Justice reported that in 2016 fourteen states passed

restrictive voting laws.

Examples of these laws are photo ID mandates, narrow times for early

voter, and limitations on voter registration. Barbour and Wright also

believe that one of the causes is restrictive voting laws but they call

this system of laws regulating the electorate.

The Constitution gives states the power to make decisions regarding

restrictive voting laws. In 2008 the Supreme Court made a crucial

decision regarding Indiana's voter ID law

in saying that it does not violate the constitution. Since then almost

half of the states have passed restrictive voting laws. These laws

contribute to Barbour and Wrights idea of the rational nonvoter. This is

someone who does not vote because the benefits of them not voting

outweighs the cost to vote.

These laws add to the “cost” of voting, or reason that make it more

difficult and to vote. In the United States programs such as MTV's "Rock the Vote" and the "Vote or Die" initiatives have been introduced to increase turnouts of those between the ages of 18 and 25. A number of governments and electoral commissions have also launched efforts to boost turnout. For instance Elections Canada has launched mass media campaigns to encourage voting prior to elections, as have bodies in Taiwan and the United Kingdom.

Google extensively studied the causes behind low voter turnout in

the United States, and argues that one of the key reasons behind lack

of voter participation is the so-called "interested bystander".

According to Google's study, 48.9% of adult Americans can be classified

as "interested bystanders", as they are politically informed but are

reticent to involve themselves in the civic and political sphere. This

category is not limited to any socioeconomic or demographic groups.

Google theorizes that individuals in this category suffer from voter apathy, as they are interested in political life but believe that their individual effect would be negligible. These individuals often participate politically on the local level, but shy away from national elections.

It has been argued that democratic consolidation (the

stabilization of new democracies) contributes to the decline in voter

turnout. A 2017 study challenges this however.

Ineligibility

Much

of the above analysis is predicated on voter turnout as measured as a

percentage of the voting-age population. In a 2001 article in the American Political Science Review,

Michael McDonald and Samuel Popkin argued, that at least in the United

States, voter turnout since 1972 has not actually declined when

calculated for those eligible to vote, what they term the

voting-eligible population.

In 1972, noncitizens and ineligible felons (depending on state law)

constituted about 2% of the voting-age population. By 2004, ineligible

voters constituted nearly 10%. Ineligible voters are not evenly

distributed across the country – 20% of California's voting-age

population is ineligible to vote – which confounds comparisons of

states. Furthermore, they argue that an examination of the Census

Bureau's Current Population Survey shows that turnout is low but not

declining among the youth, when the high youth turnout of 1972 (the

first year 18- to 20-year-olds were eligible to vote in most states) is

removed from the trendline.