Arthur C. Clarke, one of the most significant writers of hard science fiction.

Poul Anderson, author of Tau Zero, Kyrie and others.

Hard science fiction is a category of science fiction characterized by concern for scientific accuracy and logic. The term was first used in print in 1957 by P. Schuyler Miller in a review of John W. Campbell's Islands of Space in the November issue of Astounding Science Fiction. The complementary term soft science fiction, formed by analogy to hard science fiction, first appeared in the late 1970s. The term is formed by analogy to the popular distinction between the "hard" (natural) and "soft" (social) sciences. Science fiction critic Gary Westfahl argues that neither term is part of a rigorous taxonomy; instead they are approximate ways of characterizing stories that reviewers and commentators have found useful.

Stories revolving around scientific and technical consistency were written as early as the 1870s with the publication of Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

in 1870, among other stories. The attention to detail in Verne's work

became an inspiration for many future scientists and explorers, although

Verne himself denied writing as a scientist or seriously predicting

machines and technology of the future.

Scientific rigor

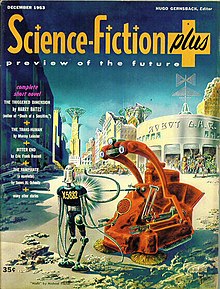

Frank R. Paul's cover for the last issue (December 1953) of Science-Fiction Plus

Hugo Gernsback believed from the beginning of his involvement with science fiction in the 1920s that the stories should be instructive, although it was not long before he found it necessary to print fantastical and unscientific fiction in Amazing Stories to attract readers.

During Gernsback's long absence from SF publishing, from 1936 to 1953,

the field evolved away from his focus on facts and education. The Golden Age of Science Fiction

is generally considered to have started in the late 1930s and lasted

until the mid-1940s, bringing with it "a quantum jump in quality,

perhaps the greatest in the history of the genre", according to science

fiction historians Peter Nicholls and Mike Ashley. However, Gernsback's views were unchanged. In his editorial in the first issue of Science-Fiction Plus,

he gave his view of the modern sf story: "the fairy tale brand, the

weird or fantastic type of what mistakenly masquerades under the name of

Science-Fiction today!" and he stated his preference for "truly

scientific, prophetic Science-Fiction with the full accent on SCIENCE". In the same editorial, Gernsback called for patent reform to give science fiction authors the right to create patents for ideas without having patent models because many of their ideas predated the technical progress needed to develop specifications for their ideas. The introduction referenced the numerous prescient technologies described throughout Ralph 124C 41+.

Carl Sagan, astronomer and adviser to NASA, also wrote the hard science fiction novel Contact.

The heart of the "hard SF" designation is the relationship of the

science content and attitude to the rest of the narrative, and (for some

readers, at least) the "hardness" or rigor of the science itself.

One requirement for hard SF is procedural or intentional: a story

should try to be accurate, logical, credible and rigorous in its use of

current scientific and technical knowledge about which technology,

phenomena, scenarios and situations that are practically and/or

theoretically possible. For example, the development of concrete

proposals for spaceships, space stations, space missions, and a US space

program in the 1950s and 1960s influenced a widespread proliferation of

"hard" space stories. Later discoveries do not necessarily invalidate the label of hard SF, as evidenced by P. Schuyler Miller, who called Arthur C. Clarke's 1961 novel A Fall of Moondust hard SF,

and the designation remains valid even though a crucial plot element,

the existence of deep pockets of "moondust" in lunar craters, is now

known to be incorrect.

There is a degree of flexibility in how far from "real science" a story can stray before it leaves the realm of hard SF. HSF authors scrupulously avoid such technology as faster-than-light travel (of which there are alternatives endorsed by NASA),

while authors writing softer SF accept such notions (sometimes referred

to as "enabling devices", since they allow the story to take place).

Readers of "hard SF" often try to find inaccuracies in stories. For example, a group at MIT concluded that the planet Mesklin in Hal Clement's 1953 novel Mission of Gravity would have had a sharp edge at the equator, and a Florida high-school class calculated that in Larry Niven's 1970 novel Ringworld the topsoil would have slid into the seas in a few thousand years.

The same book featured another inaccuracy: the eponymous Ringworld is

not in a stable orbit and would crash into the sun without active

stabilization. Niven fixed these errors in his sequel The Ringworld Engineers, and noted them in the foreword.

Films set in outer space that aspire to the hard SF label try to minimize the artistic liberties taken for the sake of practicality of effect. Factors include:

- How the film accounts for weightlessness in space.

- How the film depicts sound despite the vacuum of space.

- Whether telecommunications are instant or are limited by the speed of light.

Representative works

Larry Niven, author of Ringworld, "Inconstant Moon", "The Hole Man" and others.

Arranged chronologically by publication year.

Short stories

- Robert Heinlein, The Past Through Tomorrow collection of stories (1939-1962)

- Hal Clement, "Uncommon Sense" (1945)

- James Blish, "Surface Tension" (1952), (Book 3 of The Seedling Stars (1957)

- Tom Godwin, "The Cold Equations" (1954)

- Isaac Asimov, "Evidence" (1946)

- Poul Anderson, "Kyrie" (1968)

- Frederik Pohl, "Day Million" (1971)

- Larry Niven, "Inconstant Moon" (1971) and "The Hole Man" (1974) and "Neutron Star" (1966)

- Greg Bear, "Tangents" (1986)

- Geoffrey A. Landis, "A Walk in the Sun" (1991)

- Vernor Vinge, "Fast Times at Fairmont High" (2001)

Novels

- Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932)

- George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

- Robert A. Heinlein, The Rolling Stones (1952)

- Hal Clement, Mission of Gravity (1953)

- Harry Martinson, Aniara (1953)

- Fred Hoyle, The Black Cloud (1957)

- James Blish, A Case of Conscience (1958)

- Jack Vance, The Languages of Pao (1958)

- John Wyndham, The Outward Urge (1959)

- Stanisław Lem, Solaris (1961)

- Arthur C. Clarke, A Fall of Moondust (1961), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Rendezvous with Rama (1972)

- John Brunner, Stand on Zanzibar (1968), The Jagged Orbit (1969), The Sheep Look Up (1972), The Shockwave Rider (1975)

- Michael Crichton, The Andromeda Strain (1969)

- Poul Anderson, Tau Zero (1970)

- James Gunn, The LIsteners (1972)

- Bob Shaw, Orbitsville (1975)

- James P. Hogan, The Two Faces of Tomorrow (1979)

- Robert L. Forward, Dragon's Egg (1980)

- Steven Barnes and Larry Niven, The Descent of Anansi (1982)

- Michael Crichton, Jurassic Park (1990)

- Robert Silverberg (editor), Murasaki (1992)

- Kim Stanley Robinson, The Mars trilogy (Red Mars (1992), Green Mars (1993), Blue Mars (1996)), Aurora (2015)

- Ben Bova, Grand Tour series (1992–2009)

- Nancy Kress, Beggars in Spain (1993)

- Linda Nagata, The Nanotech Succession (1995–1998)

- Stephen Baxter, Ring (1996)

- Greg Egan, Schild's Ladder (2002)

- Alastair Reynolds, Pushing Ice (2005)

- Paul J. McAuley, The Quiet War (2008)

- James S. A. Corey, The Expanse (novel series) (2011)

- Neal Stephenson, Seveneves (2015)

Films

- Frau im Mond (1929)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

- Marooned (1969)

- Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970)

- The Andromeda Strain (1971)

- Silent Running (1972)

- Solaris (1972)

- Dark Star (1974)

- Blade Runner (1982)

- 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984) – sequel to 2001

- Contact (1997)

- Gattaca (1997)

- The Man from Earth (2007)

- Moon (2009)

- Robot & Frank (2012)

- Europa Report (2013)

- Autómata (2014)

- Ex Machina (2014)

Television

- Men into Space (1959–1960)

- Star Cops (1987)

- ReGenesis (2004–2008)

- The Expanse (2015–present)

- Mars (2016–present)

Anime / Manga

- Mobile Suit Gundam (1979)

- 2001 Nights (1984, 1986)

- They Were Eleven (1986)

- Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise (1987)

- Patlabor 2: The Movie (1993)

- Planetes (1999, 2004)

- Flag (2006)

- Pale Cocoon (2006)

- Dennō Coil (2007)

- Moonlight Mile (2007)

- Rocket Girls (2007)

- Space Brothers (2007–present)

- Eden of the East (2009)