| |

| Currency | Danish krone (DKK, kr) |

|---|---|

| calendar year | |

Trade organisations

| EU, WTO, OECD and others |

Country group

| |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP |

|

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth

|

|

GDP per capita

|

|

GDP per capita rank

| |

GDP by sector

|

|

| |

Population below poverty line

|

|

| |

Labour force

|

|

Labour force by occupation

|

|

| Unemployment |

|

Average gross salary

| DKK 38,596 / €5,179 / $5,819 monthly (2017) |

| DKK 24,315 / €3,263 / $3,666 monthly (2017) | |

Main industries

| wind turbines, pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, shipbuilding and refurbishment, iron, steel, nonferrous metals, chemicals, food processing, machinery and transportation equipment, textiles and clothing, electronics, construction, furniture and other wood products |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods

| wind turbines, pharmaceuticals, machinery and instruments, meat and meat products, dairy products, fish, furniture and design |

Main export partners

|

|

| Imports | |

Import goods

| machinery and equipment, raw materials and semimanufactures for industry, chemicals, grain and foodstuffs, consumer goods |

Main import partners

| |

FDI stock

|

|

Gross external debt

| |

| 64.6% of GDP (1 July 2018) | |

| Public finances | |

| |

| |

| Revenues | 52.0% of GDP (2018) |

| Expenses | 51.5% of GDP (2018) |

| Economic aid | ODA, 0.72% of GNI (2017) |

| |

Foreign reserves

| |

The economy of Denmark is a modern market economy with comfortable living standards, a high level of government services and transfers, and a high dependence on foreign trade. The economy is dominated by the service sector with 80% of all jobs, whereas about 11% of all employees work in manufacturing and 2% in agriculture. Nominal gross national income per capita was the tenth-highest in the world at $55,220 in 2017. Correcting for purchasing power, per capita income was Int$52,390 or 16th-highest globally. Income distribution is relatively equal, but inequality has increased somewhat during the last decades, however, due to both a larger spread in gross incomes and various economic policy measures. In 2017, Denmark had the seventh-lowest Gini coefficient (a measure of economic inequality) of the 28 European Union countries. With 5,789,957 inhabitants (1 July 2018), Denmark has the 39th largest national economy in the world measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP) and 60th largest in the world measured by purchasing power parity (PPP).

As a small open economy, Denmark generally advocates a liberal trade policy, and its exports as well as imports make up circa 50% of GDP. Since 1990 Denmark has consistently had a current account surplus, with the sole exception of 1998. As a consequence, the country has become a considerable creditor nation, having acquired a net international investment position amounting to 65% of GDP in 2018. A decisive reason for this are the widespread compulsory funded labour market pensions schemes which have caused a considerable increase in private savings rates and today play an important role for the economy.

Denmark has a very long tradition of adhering to a fixed exchange-rate system and still does so today. It is unique among OECD countries to do so while maintaining an independent currency: The Danish krone, which is pegged to the euro. Though eligible to join the EMU, the Danish voters in a referendum in 2000 rejected exchanging the krone for the euro. Whereas Denmark's neighbours like Norway, Sweden, Poland and United Kingdom generally follow inflation targeting in their monetary policy, the priority of Denmark's central bank is to maintain exchange rate stability. Consequently, the central bank has no role in domestic stabilization policy. Since February 2015, the central bank has maintained a negative interest rate in order to contain an upward exchange rate pressure.

In an international context a relatively large proportion of the population is part of the labour force, in particular because the female participation rate is very high. In 2017 78.8% of all 15-64-year-old people were active on the labour market, the sixth-highest number among all OECD countries. Unemployment is relatively low among European countries; in October 2018 4.8% of the Danish labour force were unemployed as compared to an average of 6.7% for all EU countries. There is no legal minimum wage in Denmark. The labour market is traditionally characterized by a high degree of union membership rates and collective agreement coverage. Denmark invests heavily in active labor market policies and the concept of flexicurity has been important historically.

Denmark is an example of the Nordic model, characterized by an internationally high tax level, and a correspondingly high level of government-provided services (e.g. health care, child care and education services) and income transfers to various groups like retired or disabled people, unemployed persons, students, etc. Altogether, the amount of revenue from taxes paid in 2017 amounted to 46.1% of GDP. Danish fiscal policy is generally considered healthy. Net government debt is very close to zero, amounting to 1.3% of GDP in 2017. Danish fiscal policy is characterized by a long-term outlook, taking into account likely future fiscal demands. During the 2000s a challenge was perceived to government expenditures in future decades and hence ultimately fiscal sustainability from demographic development, in particular higher longevity. Responding to this, age eligibility rules for receiving public age-related transfers were changed. From 2012 calculations of future fiscal challenges from the government as well as independent analysts have generally perceived Danish fiscal policy to be sustainable - indeed in recent years overly sustainable.

History

Denmark's

long-term economic development has largely followed the same pattern as

other Northwestern European countries. In most of recorded history Denmark has been an agricultural country with most of the population living on a subsistence level.

Since the 19th century Denmark has gone through an intense

technological and institutional development. The material standard of

living has experienced formerly unknown rates of growth, and the country

has been industrialized and later turned into a modern service society.

Almost all of the land area of Denmark is arable. Unlike most of

its neighbours, Denmark has not had extractable deposits of minerals or

fossil fuels, except for the deposits of oil and natural gas in the

North Sea, which started playing an economic role only during the 1980s.

On the other hand, Denmark has had a logistic advantage through its

long coastal line and the fact that no point on Danish land is more than

50 kilometers from the sea - an important fact for the whole period

before the industrial revolution when sea transport was cheaper than

land transport. Consequently, foreign trade has always been very important for the economic development of Denmark.

Danish silver penning from the time of Valdemar I of Denmark.

Already during the Stone Age there was some foreign trade, and even though trade has made up only a very modest share of total Danish value added

until the 19th century, it has been decisive for economic development,

both in terms of procuring vital import goods (like metals) and because

new knowledge and technological skills have often come to Denmark as a

byproduct of goods exchange with other countries. The emerging trade

implied specialization which created demand for means of payments, and the earliest known Danish coins date from the time of Svend Tveskæg around 995.

Count Otto Thott was the foremost representative of Mercantilist thought in Denmark.

According to economic historian Angus Maddison,

Denmark was the sixth-most prosperous country in the world around 1600.

The population size relative to arable agricultural land was small so

that the farmers were relatively affluent, and Denmark was

geographically close to the most dynamic and economically leading

European areas since the 16th century: the Netherlands, the northern

parts of Germany, and Britain. Still, 80 to 85% of the population lived

in small villages on a subsistence level.

Mercantilism was the leading economic doctrine during the 17th and 18th century in Denmark, leading to the establishment of monopolies like Asiatisk Kompagni, development of physical and financial infrastructure like the first Danish bank Kurantbanken in 1736 and the first "kreditforening" (a kind of building society) in 1797, and the acquisition of some minor Danish colonies like Tranquebar.

At the end of the 18th century major agricultural reforms took place that entailed decisive structural changes.

Politically, mercantilism was gradually replaced by liberal thoughts

among the ruling elite. Following a monetary reform after the Napoleonic

wars, the present Danish central bank Danmarks Nationalbank was founded in 1818.

There exist national accounting data for Denmark from 1820 onwards thanks to the pioneering work of Danish economic historian Svend Aage Hansen.

They find that there has been a substantial and permanent, though

fluctuating, economic growth all the time since 1820. The period 1822-94

saw on average an annual growth in factor incomes of 2% (0.9% per

capita) From around 1830 the agricultural sector experienced a major

boom lasting several decades, producing and exporting grains, not least

to Britain after 1846 when British grain import duties were abolished.

When grain production became less profitable in the second half of the

century, the Danish farmers made an impressive and uniquely successful

change from vegetarian to animal production leading to a new boom

period. Parallelly industrialization took off in Denmark from the 1870s. At the turn of the century industry (including artisanry) fed almost 30% of the population.

During the 20th century agriculture slowly dwindled in importance

relative to industry, but agricultural employment was only during the

1950s surpassed by industrial employment. The first half of the century

was marked by the two world wars and the Great Depression during the

1930s. After World War II Denmark took part in the increasingly close

international cooperation, joining OEEC/OECD, IMF, GATT/WTO, and from 1972 the European Economic Community, later European Union. Foreign trade increased heavily relative to GDP. The economic role of the public sector

increased considerably, and the country was increasingly transformed

from an industrial country to a country dominated by production of

services. The years 1958-73 were an unprecedented high-growth period.

The 1960s are the decade with the highest registered real per capita

growth in GDP ever, i.e. 4.5% annually.

As a chairman of the Danish Economic Council and of several policy-preparing commissions, Professor Torben M. Andersen has played an important role in Danish economic policy debates for the last decades.

During the 1970s Denmark was plunged into a crisis, initiated by the 1973 oil crisis leading to the hitherto unknown phenomenon stagflation.

For the next decades the Danish economy struggled with several major

so-called "balance problems": High unemployment, current account

deficits, inflation, and government debt. From the 1980s economic

policies have increasingly been oriented towards a long-term

perspective, and gradually a series of structural reforms have solved

these problems. In 1994 active labour market policies were introduced that via a series of labour market reforms have helped reducing structural unemployment considerably.

A series of tax reforms from 1987 onwards, reducing tax deductions on

interest payments, and the increasing importance of compulsory labour

market-based funded pensions from the 1990s have increased private

savings rates considerably, consequently transforming secular current

account deficits to secular surpluses. The announcement of a consistent

and hence more credible fixed exchange rate in 1982 has helped reducing

the inflation rate.

In the first decade of the 21st century new economic policy

issues have emerged. A growing awareness that future demographic

changes, in particular increasing longevity, could threaten fiscal sustainability,

implying very large fiscal deficits in future decades, led to major

political agreements in 2006 and 2011, both increasing the future

eligibility age of receiving public age-related pensions. Mainly because

of these changes, from 2012 onwards the Danish fiscal sustainability

problem is generally considered to be solved. Instead, issues like decreasing productivity growth rates and increasing inequality in income distribution and consumption possibilities are prevalent in the public debate.

The global Great Recession during the late 2000s, the accompanying Euro area debt crisis

and their repercussions marked the Danish economy for several years.

Until 2017, unemployment rates have generally been considered to be

above their structural level, implying a relatively stagnating economy

from a business-cycle point of view. From 2017/18 this is no longer

considered to be the case, and attention has been redirected to the need

of avoiding a potential overheating situation.

Income, wealth and income distribution

Average per capita income is high in an international context. According to the World Bank, gross national income per capita was the tenth-highest in the world at $55,220 in 2017. Correcting for purchasing power, income was Int$52,390 or 16th-highest among the 187 countries.

During the last three decades household saving rates in Denmark have increased considerably. This is to a large extent caused by two major institutional changes: A series of tax reforms from 1987 to 2009 considerably reduced the effective subsidization of private debt implicit in the rules for tax deductions of household interest payments. Secondly, compulsory funded pension schemes became normal for most employees from the 1990s. Over the years, the wealth of the Danish pension funds have accumulated so that in 2016 it constituted twice the size of Denmark's GDP.

The pension wealth consequently is a very important both for the

life-cycle of a typical individual Danish household and for the national

economy. A large part of the pension wealth is invested abroad, thus

giving rise to a fair amount of foreign capital income. In 2015, average

household assets were more than 600% of their disposable income,

among OECD countries second only to the Netherlands. At the same time,

average household gross debt was almost 300% of disposable income, which

is also at the highest level in OECD. Household balance sheets

are consequently very large in Denmark compared to most other

countries. Danmarks Nationalbank, the Danish central bank, has

attributed this to a well-developed financial system.

Income inequality

Income inequality has traditionally been low in Denmark. According to OECD figures, in 2000 Denmark had the lowest Gini coefficient of all countries. However, inequality has increased during the last decades. According to data from Statistics Denmark, the Gini coefficient for disposable income has increased from 22.1 in 1987 to 29.3 in 2017.

The Danish Economic Council found in an analysis from 2016 that the

increasing inequality in Denmark is due to several components: Pre-tax

labour income is more unequally distributed today than before, capital

income, which is generally less equally distributed than labour income,

has increased as share of total income, and economic policy is less

redistributive today, both because public income transfers play a

smaller role today and because the tax system has become less

progressive.

In international comparisons, Denmark has a relatively equal

income distribution. According to the CIA World Factbook, Denmark had

the twentieth-lowest Gini coefficient (29.0) of 158 countries in 2016. According to data from Eurostat,

Denmark was the EU country with the seventh-lowest Gini coefficient in

2017. Slovakia, Slovenia, Czechia, Finland, Belgium and the Netherlands

had a lower Gini coefficient for disposable income than Denmark.

Labour market and employment

The Danish labour market is characterized by a high degree of union membership rates and collective agreement coverage dating back from Septemberforliget (The September Settlement) in 1899 when the Danish Confederation of Trade Unions

and the Confederation of Danish Employers recognized each other's right

to organise and negotiate. The labour market is also traditionally

characterized by a high degree of flexicurity, i.e. a combination of labour market flexibility and economic security for workers. The degree of flexibility is in part maintained through active labour market policies. Denmark first introduced active labour market policies (ALMPs) in the 1990s after an economic recession that resulted in high unemployment rates. Its labour market policies are decided through tripartite cooperation between employers, employees and the government. Denmark has one of the highest expenditures on ALMPs and in 2005, spent about 1.7% of its GDP on labour market policies. This was the highest amongst the OECD countries. Similarly, in 2010 Denmark was ranked number one amongst Nordic countries for expenditure on ALMPs.

Denmark's active labour market policies particularly focus on tackling youth unemployment. They have had a "youth initiative" or the Danish Youth Unemployment Programme in place since 1996.

This includes mandatory activation for those unemployed under the age

of 30. While unemployment benefits are provided, the policies are

designed to motivate job-seeking. For example, unemployment benefits

decrease by 50% after 6 months.

This is combined with education, skill development and work training

programs. For instance, the Building Bridge to Education program was

started in 2014 to provide mentors and skill development classes to

youth that are at risk of unemployment. Such active labour market policies

have been successful for Denmark in the short-term and the long-term.

For example, 80% of participants in the Building Bridge for Education

program felt that "the initiative has helped them to move towards

completing an education".

On a more macro scale, a study of the impact of ALMPs in Denmark

between 1995 and 2005 showed that such policies had positive impact not

just on employment but also on earnings.

The effective compensation rate for unemployed workers has been

declining for the last decades, however. Unlike in most Western

countries there is no legal minimum wage in Denmark.

A relatively large proportion of the population is active on the

labour market, not least because of a very high female participation

rate. The total participation rate for people aged 15 to 64 years was

78.8% in 2017. This was the 6th-highest number among OECD countries,

only surpassed by Iceland, Switzerland, Sweden, New Zealand and the Netherlands. The average for all OECD countries together was 72.1%.

According to Eurostat,

the unemployment rate was 5.7% in 2017. This places unemployment in

Denmark somewhat below the EU average, which was 7.6%. 10 EU member

countries had a lower unemployment rate than Denmark in 2017.

Altogether, total employment in 2017 amounted to 2,919,000 people according to Statistics Denmark.

The share of employees leaving jobs every year (for a new job, retirement or unemployment) in the private sector is around 30%

- a level also observed in the U.K. and U.S.- but much higher than in

continental Europe, where the corresponding figure is around 10%, and in

Sweden. This attrition can be very costly, with new and old employees

requiring half a year to return to old productivity levels, but with

attrition bringing the number of people that have to be fired down.

Foreign trade

As a small open economy,

Denmark is very dependent on its foreign trade. In 2017, the value of

total exports of goods and services made up 55% of GDP, whereas the

value of total imports amounted to 47% of GDP. Trade in goods made up

slightly more than 60% of both exports and imports, and trade in

services the remaining close to 40%.

Machinery, chemicals and related products like medicine and

agricultural products were the largest groups of export goods in 2017. Service exports were dominated by freight sea transport services from the Danish merchant navy.

Most of Denmark's most important trading partners are neighbouring

countries. The five main importers of Danish goods and services in 2017

were Germany, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Norway. The five

countries from which Denmark imported most goods and services in 2017

were Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, China and United Kingdom.

After having almost consistently an external balance of payments current account

deficit since the beginning of the 1960s, Denmark has maintained a

surplus on its BOP current account for every year since 1990, with the

single exception of 1998. In 2017, the current account surplus amounted

to approximately 8% of GDP. Consequently, Denmark has changed from a net debtor to a net creditor country. By 1 July 2018, the net foreign wealth or net international investment position of Denmark was equal to 64.6% of GDP, Denmark thus having the largest net foreign wealth relative to GDP of any EU country.

As the annual current account is equal to the value of domestic saving minus total domestic investment,

the change from a structural deficit to a structural surplus is due to

changes in these two national account components. In particular, the

Danish national saving rate in financial assets

increased by 11 per cent of GDP from 1980 to 2015. Two main reasons for

this large change in domestic saving behaviour were the growing

importance of large-scale compulsory pension schemes and several Danish

fiscal policy reforms during the period which considerably decreased tax deductions of household interest expense, thus reducing the tax subsidy to private debt.

Currency and monetary policy

The building of Danmarks Nationalbank, the central bank of Denmark, built by the Danish architect Arne Jacobsen.

The Danish currency is the Danish krone, subdivided into 100 øre. The krone and øre were introduced in 1875, replacing the former rigsdaler and skilling. Denmark has a very long tradition of maintaining a fixed exchange-rate system, dating back to the period of the gold standard during the time of the Scandinavian Monetary Union from 1873 to 1914. After the breakdown of the international Bretton Woods system in 1971, Denmark devalued

the krone repeatedly during the 1970s and the start of the 1980s,

effectively maintaining a policy of "fixed, but adjustable" exchange

rates. Rising inflation led to Denmark declaring a more consistent fixed

exchange-rate policy in 1982. At first, the krone was pegged to the European Currency Unit or ECU, from 1987 to the Deutschmark, and from 1999 to the euro.

Although eligible, Denmark chose not to join the European Monetary Union when it was founded. In 2000, the Danish government advocated Danish EMU membership and called a referendum to settle the issue.

With a turn-out of 87.6%, 53% of the voters rejected Danish membership.

Occasionally, the question of calling another referendum on the issue

has been discussed, but since the Financial crisis of 2007–2008 opinion polls have shown a clear majority against Denmark joining the EMU, and the question is not high on the political agenda presently.

Maintenance of the fixed exchange rate is the responsibility of Danmarks Nationalbank, the Danish central bank.

As a consequence of the exchange rate policy, the bank must always

adjust its interest rates in order to ensure a stable exchange rate and

consequently cannot at the same time conduct monetary policy in order to stabilize e.g. domestic inflation or unemployment rates. This makes the conduct of stabilization policy

fundamentally different from the situation in Denmark's neighbouring

countries like Norway, Sweden, Poland og United Kingdom, in which the

central banks have a central stabilizing role. Denmark is presently the

only OECD member country maintaining an independent currency with a

fixed exchange rate. Consequently, the Danish krone is the only currency

in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II).

In the first months of 2015, Denmark experienced the largest

pressure against the fixed exchange rate for many years because of very

large capital inflows, causing a tendency for the Danish krone to

appreciate.

Danmarks Nationalbank reacted in various ways, chiefly by lowering its

interest rates to record low levels. On 6 February 2015 the certificates

of deposit rate, one of the four official Danish central bank rates,

was lowered to -0.75%. In January 2016 the rate was raised to -0.65%, at

which level it has been maintained since then.

Inflation in Denmark as measured by the official consumer price index of Statistics Denmark was 1.1% in 2017.

Inflation has generally been low and stable for the last decades.

Whereas in 1980 annual inflation was more than 12%, in the period

2000-2017 the average inflation rate was 1.8%.

Government

Overall organization

Since

a local-government reform in 2007, the general government organization

in Denmark is carried out on three administrative levels: central

government, regions, and municipalities. Regions administer mainly

health care services, whereas municipalities administer primary

education and social services. Municipalities in principle independently

levy income and property taxes, but the scope for total municipal

taxation and expenditure is closely regulated by annual negotiations

between the municipalities and the Finance Minister of Denmark. At the central government level, the Ministry of Finance

carries out the coordinating role of conducting economic policy. In

2012, the Danish parliament passed a Budget Law (effective from January

2014) which governs the over-all fiscal framework, stating among other

things that the structural deficit must never exceed 0.5% of GDP, and that Danish fiscal policy is required to be sustainable, i.e. have a non-negative fiscal sustainability indicator. The Budget Law also assigned the role of independent fiscal institution (IFI, informally known as "fiscal watchdog") to the already-existing independent advisory body of the Danish Economic Councils.

Budget and fiscal position

Danish

fiscal policy is generally considered healthy. Government net debt was

close to zero at the end of 2017, amounting to DKK 27.3 billion, or 1.3%

of GDP.

The government sector having a fair amount of financial assets as well

as liabilities, government gross debt amounted to 36.1% of GDP at the

same date.

The gross EMU-debt as percentage of GDP was the sixth-lowest among all

28 EU member countries, only Estonia, Luxembourg, Bulgaria, the Czech

Republic and Romania having a lower gross debt. Denmark had a government budget surplus of 1.1% of GDP in 2017.

Long-run annual fiscal projections from the Danish government as

well as the independent Danish Economic Council, taking into account

likely future fiscal developments caused by demographic developments

etc. (e.g. a likely ageing of the population caused by a considerable

expansion of life expectancy),

consider the Danish fiscal policy to be overly sustainable in the long

run. In Spring 2018, the so-called Fiscal Sustainability Indicator was

calculated to be 1.2 (by the Danish government) respectively 0.9% (by

the Danish Economic Council) of GDP.

This implies that under the assumptions employed in the projections,

fiscal policy could be permanently loosened (via more generous public

expenditures and/or lower taxes) by ca. 1% of GDP while still

maintaining a stable government debt-to-GDP ratio in the long run.

Taxation

The tax level as well as the government expenditure level in Denmark

ranks among the highest in the world, which is traditionally ascribed to

the Nordic model of which Denmark is an example, including the welfare state principles which historically evolved during the 20th century. In 2017, the official Danish tax level amounted to 46.1% of GDP. The all-record highest Danish tax level was 49.8% of GDP,

reached in 2014 because of high extraordinary one-time tax revenues

caused by a reorganization of the Danish-funded pension system. The

Danish tax-to-GDP-ratio of 46% was the second-highest among all OECD

countries, second only to France. The OECD average was 34.2%.

The tax structure of Denmark (the relative weight of different taxes)

also differs from the OECD average, as the Danish tax system in 2015 was

characterized by substantially higher revenues from taxes on personal

income, whereas on the other hand, no revenues at all derive from social

security contributions. A lower proportion of revenues in Denmark

derive from taxes on corporate income and gains and property taxes than

in OECD generally, whereas the proportion deriving from payroll taxes,

VAT, and other taxes on goods and services correspond to the OECD

average.

In 2016, the average marginal tax rate on labour income for all Danish tax-payers was 38.9%. The average marginal tax on personal capital income was 30.7%.

Professor of Economics at Princeton University Henrik Kleven

has suggested that three distinct policies in Denmark and its

Scandinavian neighbours imply that the high tax rates cause only

relatively small distortions to the economy: widespread use of

third-party information reporting for tax collection purposes (ensuring a

low level of tax evasion), broad tax bases (ensuring a low level of tax avoidance), and a strong subsidization of goods that are complementary to working (ensuring a high level of labour force participation).

Government Expenditures

Parallel

to the high tax level, government expenditures make up a large part of

GDP, and the government sector carries out many different tasks. By

September 2018, 831,000 people worked in the general government sector,

corresponding to 29.9% of all employees.

In 2017, total government expenditure amounted to 50.9% of GDP.

Government consumption took up precisely 25% of GDP (e.g. education and

health care expenditure), and government investment (infrastructure

etc.) expenditure another 3.4% of GDP. Personal income transfers (for

e.g. elderly or unemployed people) amounted to 16.8% of GDP.

Denmark has an unemployment insurance system called the A-kasse (arbejdsløshedskasse).

This system requires a paying membership of a state-recognized

unemployment fund. Most of these funds are managed by trade unions, and

part of their expenses are financed through the tax system. Members of

an A-kasse are not obliged to be members of a trade union.

Not every Danish citizen or employee qualifies for a membership of an

unemployment fund, and membership benefits will be terminated after 2

years of unemployment. A person that is not a member of an A-kasse cannot receive unemployment benefits.

Unemployment funds do not pay benefits to sick members, who will be

transferred to a municipal social support system instead. Denmark has a

countrywide, but municipally administered social support system against

poverty, securing that qualified citizens have a minimum living income.

All Danish citizens above 18 years of age can apply for some financial

support if they cannot support themselves or their family. Approval is

not automatic, and the extent of this system has generally been

diminished since the 1980s. Sick people can receive some financial

support throughout the extent of their illness. Their ability to work

will be re-evaluated by the municipality after 5 months of illness.

The welfare system related to the labor market has experienced

several reforms and financial cuts since the late 1990s due to political

agendas for increasing the labor supply. Several reforms of the rights

of the unemployed have followed up, partially inspired by the Danish

Economic Council.

Halving the time unemployment benefits can be received from four to two

years, and making it twice as hard to regain this right, was

implemented in 2010 for example.

Disabled people can apply for permanent social pensions. The

extent of the support depends on the ability to work, and people below

40 can not receive social pension unless they are deemed incapable of

any kind of work.

Industries

Agriculture

Pasture grazing cattle (Rømø)

Agriculture was once the most important industry in Denmark.

Nowadays, it is of minor economic importance. In 2016, 62,000 people, or

2.5% of all employed people worked in agriculture and horticulture.

Another 2,000 people worked in fishing.

As value added per person is relatively low, the share of national

value added is somewhat lower. Total gross value added in agriculture,

forestry and fishing amounted to 1.6% of total output in Denmark (in

2017).

Despite this, Denmark is still home to various types of agricultural

production. Within animal husbandry, it includes dairy and beef cattle,

pigs, poultry and fur animals (primarily mink) - all sectors that

produce mainly for export. Regarding vegetable production, Denmark is a

leading producer of grass-, clover- and horticultural seeds. The

agriculture and food sector as a whole represented 25% of total Danish

commodity exports in 2015.

63% of the land area of Denmark is used for agricultural production - the highest share in the world according to a report from University of Copenhagen in 2017. The Danish agricultural industry is historically characterized by freehold and family ownership, but due to structural development farms have become fewer and larger. In 2017 the number of farms was approximately 35,000, of which approximately 10,000 were owned by full-time farmers.

Animal production

The

tendency toward fewer and larger farms has been accompanied by an

increase in animal production, using fewer resources per produced unit.

The number of dairy farmers has reduced to about 3,800 with an

average herd size of 150 cows. The milk quota is 1,142 tonnes. Danish

dairy farmers are among the largest and most modern producers in Europe.

More than half of the cows live in new loose-housing systems. Export of

dairy products accounts for more than 20 percent of the total Danish

agricultural export. The total number of cattle in 2011 was

approximately 1.5 million. Of these, 565,000 were dairy cows and 99,000

were suckler cows. The yearly number of slaughtering of beef cattle is

around 550,000.

For more than 100 years the production of pigs and pig meat was a

major source of income in Denmark. The Danish pig industry is among the

world's leaders in areas such as breeding, quality, food safety, animal

welfare and traceability creating the basis for Denmark being among the

world's largest pig meat exporters. Approximately 90 percent of the

production is exported. This accounts for almost half of all

agricultural exports and for more than 5 percent of Denmark's total

exports. About 4,200 farmers produce 28 million pigs annually. Of these,

20.9 million are slaughtered in Denmark.

Fur animal production on an industrial scale started in the 1930s in Denmark. Denmark is now the world's largest producer of mink

furs, with 1,400 mink farmers fostering 17.2 million mink and producing

around 14 million furs of the highest quality every year.

Approximately 98 percent of the skins sold at Kopenhagen Fur Auction

are exported. Fur ranks as Danish agriculture's third largest export

article, at more than DKK 7 billion annually. The number of farms peaked

in the late 1980s at more than 5,000 farms, but the number has declined

steadily since, as individual farms grew in size. Danish mink farmers claim their business to be sustainable,

feeding the mink food industry waste and using all parts of the dead

animal as meat, bone meal and biofuel. Special attention is given to the

welfare of the mink, and regular "Open Farm" arrangements are made for

the general public. Mink thrive in, but are not a native to Denmark, and it is considered an invasive species. American Mink are now widespread in Denmark and continues to cause problems for the native wildlife, in particular waterfowl. Denmark also has a small production of fox, chinchilla and rabbit furs.

Two hundred professional producers are responsible for the Danish

egg production, which was 66 million kg in 2011. Chickens for slaughter

are often produced in units with 40,000 broilers. In 2012, 100 million

chickens were slaughtered. In the minor productions of poultry, 13

million ducks, 1.4 million geese and 5.0 million turkeys were

slaughtered in 2012.

Organic production

Organic farming

and production has increased considerably and continuously in Denmark

since 1987 when the first official regulations of this particular

agricultural method came into effect. In 2017, the export of organic

products reached DK 2.95 billion, a 153% increase from 2012 five years

earlier, and a 21% increase from 2016. The import of organic products

has always been higher than the exports though and reached DK 3.86

billion in 2017. After some years of stagnation, close to 10% of the

cultivated land is now categorized as organically farmed, and 13.6% for

the dairy industry, as of 2017.

Denmark has the highest retail consumption share for organic

products in the world. In 2017, the share was at 13.3%, accounting for a

total of DKK 12.1 billion.

Natural resource extraction

Denmark has some sources of oil and natural gas in the North Sea with Esbjerg

being the main city for the oil and gas industry. Production has

decreased in recent years, though. Whereas in 2006 output (measured as gross value added or GVA) in mining and quarrying industries made up more than 4% of Denmarks's total GVA, in 2017 it amounted to 1.2%.

The sector is very capital-intensive, so the share of employment is

much lower: About 2,000 persons worked in the oil and gas extraction

sector in 2016, and another 1,000 persons in extraction of gravel and

stone, or in total about 0.1% of total employment in Denmark.

Engineering and High-tech

Denmark

houses a number of significant engineering and high-technology firms,

within the sectors of industrial equipment, aerospace, robotics,

pharmaceutical and electronics.

Electronics and industrial equipment

Danfoss, headquartered in Sønderborg, designs and manufactures industrial electronics, heating and cooling equipment, as well as drivetrains and power solutions.

Denmark is also a large exporter of pumps, with the company Grundfos holding 50% of the market share, manufacturing circulation pumps.

Manufacturing

In 2017 total output (gross value added) in manufacturing industries amounted to 14.4% of total output in Denmark.

325,000 people or a little less than 12% of all employed persons worked

in manufacturing (including utilities, mining and quarrying) in 2016. Main sub-industries are manufacture of pharmaceuticals, machinery, and food products.

Service industry

In 2017 total output (gross value added) in service industries amounted to 75.2% of total output in Denmark, and 79.9% of all employed people worked here (in 2016).

Apart from public administration, education and health services, main

service sub-industries were trade and transport services, and business

services.

Transport

Copenhagen Central Station with S-Trains.

Significant investment has been made in building road and rail links between Copenhagen and Malmö, Sweden (the Øresund Bridge), and between Zealand and Funen (the Great Belt Fixed Link). The Copenhagen Malmö Port was also formed between the two cities as the common port for the cities of both nations.

The main railway operator is Danske Statsbaner (Danish State Railways) for passenger services and DB Schenker Rail for freight trains. The railway tracks are maintained by Banedanmark. Copenhagen has a small Metro system, the Copenhagen Metro and the greater Copenhagen area has an extensive electrified suburban railway network, the S-train.

Private vehicles are increasingly used as a means of transport. New cars are taxed by means of a registration tax (85% to 150%) and VAT (25%). The motorway network now covers 1,300 km.

Denmark is in a strong position in terms of integrating

fluctuating and unpredictable energy sources such as wind power in the

grid. It is this knowledge that Denmark now aims to exploit in the

transport sector by focusing on intelligent battery systems (V2G) and plug-in vehicles.

Energy

Denmark has invested heavily in windfarms. In 2015, 42% of the domestic electricity consumption comes from wind.

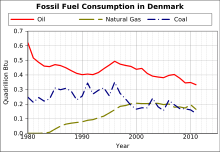

Fossil fuel consumption in Denmark.

Denmark has changed its energy consumption from 99% fossil fuels (92%

oil (all imported) and 7% coal) and 1% biofuels in 1972 to 73% fossil

fuels (37% oil (all domestic), 18% coal and 18% natural gas (all

domestic)) and 27% renewables (largely biofuels) in 2015. The goal is a

full independence of fossil fuels

by 2050. This drastic change was initially inspired largely by the

discovery of Danish oil and gas reserves in the North Sea in 1972 and

the 1973 oil crisis. The course took a giant leap forward in 1984, when the Danish North Sea oil and gas fields, developed by native industry in close cooperation with the state, started major productions. In 1997, Denmark became self-sufficient with energy and the overall CO2 emission from the energy sector began to fall by 1996. Wind energy contribution to the total energy consumption has risen from 1% in 1997 to 5% in 2015.

Since 2000, Denmark has increased gross domestic product (GDP) and at the same time decreased energy consumption. Since 1972, the overall energy consumption has dropped by 6%, even though the GDP has doubled in the same period. Denmark had the 6th best energy security in the world in 2014.

Denmark has had relatively high energy taxation to encourage careful

use of energy since the oil crises in the 1970s, and Danish industry has

adapted to this and gained a competitive edge.

The so-called "green taxes" have been broadly criticised partly for

being higher than in other countries, but also for being more of a tool

for gathering government revenue than a method of promoting "greener"

behaviour.

| Oil | Gasoline | Natural gas | Coal | Electricity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excise&VAT | 9.3 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 11.7 |

Denmark has low electricity costs (including costs for cleaner energy) in EU, but general taxes (11.7 billion DKK in 2015)[118] make the electricity price for households the highest in Europe. As of 2015, Denmark has no environment tax on electricity.

Denmark is a long time leader in wind energy and a prominent exporter of Vestas and Siemens wind turbines, and as of May 2011

Denmark derives 3.1% of its gross domestic product from renewable

(clean) energy technology and energy efficiency, or around €6.5 billion

($9.4 billion).

It has integrated fluctuating and less predictable energy sources such

as wind power into the grid. Wind produced the equivalent of 43% of

Denmark's total electricity consumption in 2017. The share of total energy production is smaller: In 2015, wind accounted for 5% of total Danish energy production.

Energinet.dk is the Danish national transmission system operator for electricity and natural gas. The electricity grids of western Denmark and eastern Denmark were not connected until 2010 when the 600MW Great Belt Power Link went into operation.

Cogeneration plants are the norm in Denmark, usually with district heating which serves 1.7 million households.

Waste-to-energy incinerators produce mostly heating and hot water. Vestforbrænding in Glostrup Municipality

operates Denmark's largest incinerator, a cogeneration plant which

supplies electricity to 80,000 households and heating equivalent to the

consumption in 63,000 households (2016). Amager Bakke is an example of a new incinerator being built.

Greenland and the Faroe Islands

In addition to Denmark proper, the Kingdom of Denmark comprises two autonomous constituent countries in the North Atlantic Ocean: Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Both use the Danish krone as their currency, but form separate economies, having separate national accounts

etc. Both countries receive an annual fiscal subsidy from Denmark which

amounts to about 25% of Greenland's GDP and 11% of Faroese GDP. For both countries, fishing industry is a major economic activity.

Neither Greenland nor the Faroe Islands are members of the European Union. Greenland left the European Economic Community in 1986, and the Faroe Islands declined membership in 1973, when Denmark joined.