The German battleship Schleswig-Holstein attacked Westerplatte at the start of the war, September 1, 1939

Destroyer USS Shaw exploding during the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941

Historians from many countries have given considerable attention to studying and understanding the causes of World War II, a global war from 1939 to 1945 that was the deadliest conflict in human history. The immediate precipitating event was the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany on September 1, 1939, and the subsequent declarations of war on Germany made by Britain and France,

but many other prior events have been suggested as ultimate causes.

Primary themes in historical analysis of the war's origins include the

political takeover of Germany in 1933 by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party; Japanese militarism against China; Italian aggression against Ethiopia; and Germany's initial success in negotiating a neutrality pact with the Soviet Union to divide territorial control of Eastern Europe between them.

During the interwar period, deep anger arose in Weimar Germany regarding the conditions of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which punished Germany for its role in the First World War with severe conditions and heavy financial reparations in order to prevent it from ever becoming a military power again. This provoked strong currents of revanchism in German politics, with complaints primarily focused on the demilitarization of the Rhineland, the prohibition of German unification with Austria, and the loss of some German-speaking territories and overseas colonies.

The 1930s were a decade in which democracy was in disrepute;

countries across the world turned to authoritarian regimes during the

worldwide economic crisis of the Great Depression.

In Germany, resentment and hatred of other countries was intensified by

the instability of the German political system, as many activists

rejected the legitimacy of the Weimar Republic. The most extreme

political aspirant to emerge from this situation was Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi Party. The Nazis took totalitarian power in Germany

beginning in 1933 and demanded the undoing of the Versailles

provisions. Their ambitious and aggressive domestic and foreign policies

reflected the Nazi ideologies of anti-Semitism, unification of all Germans, the acquisition of "living space" (Lebensraum) for agrarian settlers, the elimination of Bolshevism, and the hegemony of an "Aryan"/"Nordic" master race over "sub-humans" (Untermenschen) such as Jews and Slavs. Other factors leading to the war included aggression by Fascist Italy against Ethiopia and Albania, and by Imperial Japan against much of East Asia, resulting in the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the gradual annexation of most of China.

At first, these aggressive moves met with only feeble and ineffectual policies of appeasement from the other major world powers. The League of Nations, established after the First World War, proved helpless regarding China and Ethiopia. A decisive proximate event was the 1938 Munich Conference, which formally approved Germany's annexation of the Sudetenland

from Czechoslovakia. Hitler promised it was his last territorial claim,

but in early 1939 he became even more aggressive, and European

governments finally realized that appeasement was not guaranteeing

peace. Britain and France badly fumbled diplomatic efforts to form a

military alliance with the Soviet Union, and Hitler instead offered

Stalin a better deal in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939. An alliance formed by Germany, Japan, and Italy led to the establishment of the Axis Powers.

Ultimate causes

Legacies of the First World War

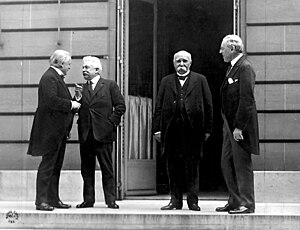

"The Big Four" made all the major decisions at the Paris Peace Conference (from left to right, David Lloyd George of Britain, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando of Italy, Georges Clemenceau of France, Woodrow Wilson of the U.S.)

By the end of World War I in late 1918, the world's social and geopolitical circumstances had fundamentally and irrevocably changed. The Allies

had been victorious, but many of Europe's economies and infrastructures

were devastated, including those of the victors. France, along with the

other victor countries, was in a desperate situation regarding its

economy, security, and morale, and understood that its position in 1918

was "artificial and transitory". Thus, Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau worked to gain French security via the Treaty of Versailles, and French security demands, such as reparations, coal payments, and a demilitarized Rhineland, took precedence at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920,

which designed the treaty. The war "must be someone's fault – and

that's a very natural human reaction" analyzed historian Margaret

MacMillan. Germany was charged with the sole responsibility of starting World War I, and the "War Guilt Clause"

was the first step towards a satisfying revenge for the victor

countries, namely France, against Germany. Ginsberg argues, "France was

greatly weakened and, in its weakness and fear of a resurgent Germany,

sought to isolate and punish Germany....French revenge would come back

to haunt France during the Nazi invasion and occupation twenty years

later."

Germany after Versailles

Administered by the League of Nations

Annexed or transferred to neighboring countries by the treaty, or later via plebiscite and League of Nation action

The two main provisions of the French security agenda were war reparations from Germany in the form of money and coal and a detached German Rhineland.

The French government printed excess currency, which created inflation,

to compensate for the lack of funds, in addition to borrowing money

from the United States. Reparations from Germany were necessary to

stabilize the French economy.

France also demanded that Germany give France its coal supply from the

Ruhr to compensate for the destruction of French coal mines during the

war. The French demanded an amount of coal that was a "technical

impossibility" for the Germans to pay back. France also insisted on the demilitarization

of the German Rhineland in the hope of hindering any possibility of a

future German attack. This gave France a physical security barrier

between itself and Germany.

The inordinate amount of reparations, coal payments, and the principle

of a demilitarized Rhineland were largely viewed by the Germans as

insulting and unreasonable.

The resulting Treaty of Versailles

brought a formal end to the war but was criticized by governments on

all sides of the conflict: it was neither lenient enough to appease Germany, nor harsh enough to prevent it from becoming a dominant continental power again. The German people largely viewed the treaty as placing the blame, or "war guilt", on Germany and Austria-Hungary

and punishing them for their "responsibility", rather than working out

an agreement that would assure long-term peace. The treaty imposed harsh

monetary reparations as well as demilitarization requirements and territorial dismemberment, and caused mass ethnic resettlement, separating millions of ethnic Germans into neighboring countries.

In the effort to pay war reparations to Britain and France, the Weimar Republic printed trillions of marks, causing extremely high inflation. "No postwar German government believed it could accept such a burden on future generations and survive ...".

Paying reparations to the victorious side was a traditional punishment

with a long history of use, but in this instance it was the "extreme

immoderation" that caused German resentment. Germany did not make its

last World War I reparation payment until 3 October 2010,

ninety-two years after the end of the war. Germany also fell behind in

their coal payments because of a passive resistance movement against the

French.

In response, the French invaded the Ruhr and occupied it. By this point

the majority of Germans were enraged with the French and placed the

blame for their humiliation on the Weimar Republic. Adolf Hitler, a

leader of the Nazi Party, attempted a coup d'état of the Republic in

1923 known as the Beer Hall Putsch, through which he intended to establish a Greater German Reich. Although this failed, Hitler gained recognition as a national hero among the German population.

During the war, German colonies outside Europe had been annexed by the Allies, and Italy took the southern half of Tyrol after an armistice was agreed upon. The war in the east ended with the defeat and collapse of the Russian Empire, and German troops had occupied large parts of Eastern and Central Europe (with varying degrees of control), establishing various client states such as a kingdom of Poland and the United Baltic Duchy. After the destructive and indecisive Battle of Jutland in 1916 and the mutiny of its sailors in 1917, the Kaiserliche Marine

spent most of the war in port, only to be turned over to the Allies and

scuttled at surrender by its own officers. Decades later, the lack of

an obvious military defeat would be one of the pillars holding together

the Dolchstosslegende ("Stab-in-the-back myth"), giving the Nazis another propaganda tool.

The demilitarized Rhineland

and additional cutbacks on military also infuriated the Germans.

Although it is logical that France would want the Rhineland to be a

neutral zone, the fact that France had the power to make that desire

happen merely exacerbated German resentment of the French. In addition,

the Treaty of Versailles dissolved the German general staff, and

possession of navy ships, aircraft, poison gas, tanks, and heavy

artillery was made illegal.

The humiliation of being bossed around by the victor countries,

especially France, and being stripped of their prized military made the

Germans resent the Weimar Republic and idolize anyone who stood up to

it. Austria also found the treaty unjust, which encouraged Hitler's popularity.

These conditions generated bitter resentment towards the war's

victors, who had promised the people of Germany that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points

would be a guideline for peace; however, the United States played only a

minor role in World War I and Wilson could not convince the Allies to

agree to adopt his Fourteen Points. Many Germans felt that the German

government had agreed to an armistice based on this understanding, while others felt that the German Revolution of 1918–1919

had been orchestrated by the "November criminals" who later assumed

office in the new Weimar Republic. The Japanese also started to express

resentment against the countries of Western Europe due to the way they

were treated during the negotiations of the Treaty of Versailles; their

proposition to start bringing the issue of the current racial equality

was not put in the final draft and was hardly talked about at the table

with nothing given in reward for Japanese participation in the war. The economic and psychological legacies of the First World War persisted well into the interwar period.

Failure of the League of Nations

The League of Nations was an international peacekeeping organization founded after World War I with the explicit goal of preventing future wars. The League's methods included disarmament, collective security,

settling disputes between countries through negotiation diplomacy, and

improving global welfare. The diplomatic philosophy behind the League

represented a fundamental shift in thought from the preceding century.

The old philosophy of "concert of nations", growing out of the Congress of Vienna (1815), saw Europe as a shifting map of alliances among nation-states, creating a balance of power

maintained by strong armies and secret agreements. Under the new

philosophy, the League would act as a government of governments, with

the role of settling disputes between individual nations in an open and

legalist forum. Despite President of the United States Woodrow Wilson

being the League's chief architect, the United States never joined the

League of Nations, which lessened its power and credibility—the addition

of a burgeoning industrial and military world power such as the United

States might have added more force behind the League's demands and

requests.

The official opening of the League of Nations, 15 November 1920

The League lacked an armed force of its own and so depended on member

nations to enforce its resolutions, uphold economic sanctions that the

League ordered, or provide an army when needed for the League to use.

However, individual governments were often very reluctant to do so.

After numerous notable successes and some early failures in the 1920s,

the League ultimately proved incapable of preventing aggression by the Axis Powers

in the 1930s. The reliance upon unanimous decisions, the lack of an

independent body of armed forces, and the continued self-interest of its

leading members meant that this failure was arguably inevitable.

Expansionism and militarism

Expansionism

is the doctrine of expanding the territorial base (or economic

influence) of a country, usually by means of military aggression. Militarism is the principle or policy of maintaining a strong military

capability to use aggressively to expand national interests and/or

values, with the view that military efficiency is the supreme ideal of a

state.

Though the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations had sought to stifle expansionist and militarist policies by all actors, the conditions their creators had imposed on the world's new geopolitical situation and the technological circumstances of the era only emboldened the re-emergence of these ideologies during the interwar period. By the early 1930s, a highly militaristic and aggressive national ideology prevailed in Germany, Japan, and Italy. This attitude fueled advancements in military technology, subversive propaganda, and ultimately territorial expansion as well. It is has been observed that the leaders of countries that have been suddenly militarized often feel a need to prove that their armies are formidable, and this was often a contributing factor in the start of conflicts in the interwar period such as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and the Second Sino-Japanese War.

In Italy, Benito Mussolini sought to create a New Roman Empire based around the Mediterranean. It invaded Ethiopia as early as 1935, Albania in early 1938, and later invaded Greece. This provoked angry words and an oil embargo from the League of Nations, which failed.

Under the Nazi regime, Germany began its own program of

expansion, seeking to restore the "rightful" boundaries of historic

Germany. As a prelude toward these goals the Rhineland was remilitarized in March 1936. Also of importance was the idea of a Greater Germany, supporters of which hoped to unite the German people

under one nation state, which included all territories where Germans

lived, regardless of whether they happened to be a minority in a

particular territory. After the Treaty of Versailles, a unification

between Germany and a newly formed German-Austria, a successor rump state of Austria-Hungary, was prohibited by the Allies despite the majority of Austrian Germans supporting such a union.

During the period of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), the Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup d'état

against the republican government, was launched by disaffected members

of the armed forces. After this event, some of the more radical

militarists and nationalists were submerged in grief and despair into

the NSDAP,

while more moderate elements of militarism declined. The result was an

influx of militarily inclined men into the Nazi Party which, when

combined with their racial theories, fueled irredentist sentiments and put Germany on a collision course for war with its immediate neighbors.

Japanese march into Zhengyangmen of Beijing after capturing the city in July 1937

In Asia, the Empire of Japan harbored expansionist desires towards Manchuria and the Republic of China. Two contemporaneous factors in Japan

contributed both to the growing power of its military and chaos within

its ranks leading up to the Second World War. One was the Cabinet Law, which required the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy

(IJN) to nominate cabinet members before changes could be formed. This

essentially gave the military veto power over the formation of any

Cabinet in the ostensibly parliamentary country. The other factor was gekokujō, or institutionalized disobedience

by junior officers. It was not uncommon for radical junior officers to

press their goals to the extent of assassinating their seniors. In 1936,

this phenomenon resulted in the February 26 Incident, in which junior officers attempted a coup d'état and killed leading members of the Japanese government. In the 1930s, the Great Depression

wrecked Japan's economy and gave radical elements within the Japanese

military the chance to force the entire military into working towards

the conquest of all of Asia. For example, in 1931 the Kwantung Army (a Japanese military force stationed in Manchuria) staged the Mukden Incident, which sparked the invasion of Manchuria and its transformation into the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo.

Germans vs Slavs

Twentieth-century events marked the culmination of a millennium-long process of intermingling between Germans and Slavic peoples.

The rise of nationalism in the 19th century made race a centerpiece of

political loyalty. The rise of the nation-state had given way to the

politics of identity, including pan-Germanism and pan-Slavism. Furthermore, social Darwinist theories framed the coexistence as a "Teuton vs. Slav" struggle for domination, land, and limited resources. Integrating these ideas into their own worldview, the Nazis believed that the Germans, the "Aryan race", were the master race and that the Slavs were inferior.

Japan's seizure of resources and markets

Japanese occupation of China in 1937

Other than a few coal and iron deposits, and a small oil field on Sakhalin Island, Japan lacked strategic mineral resources. At the start of the 20th century in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan had succeeded in pushing back the East Asian expansion of the Russian Empire in competition for Korea and Manchuria.

Japan's goal after 1931 was economic dominance of most of East

Asia, often expressed in Pan-Asian terms of "Asia for the Asians.".

Japan was determined to dominate the China market, which the U.S. and

other European powers had been dominating. On October 19, 1939, the

American Ambassador to Japan, Joseph C. Grew, in a formal address to the

America-Japan Society stated:

the new order in East Asia has appeared to include, among other things, depriving Americans of their long established rights in China, and to this the American people are opposed ... American rights and interests in China are being impaired or destroyed by the policies and actions of the Japanese authorities in China.

In 1937 Japan invaded Manchuria and China proper. Under the guise of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,

with slogans as "Asia for the Asians!" Japan sought to remove the

Western powers' influence in China and replace it with Japanese

domination.

The ongoing conflict in China led to a deepening conflict with the U.S., where public opinion was alarmed by events such as the Nanking Massacre and growing Japanese power. Lengthy talks were held between the U.S. and Japan. When Japan moved into the southern part of French Indochina,

President Roosevelt chose to freeze all Japanese assets in the U.S. The

intended consequence of this was the halt of oil shipments from the

U.S. to Japan, which had supplied 80 percent of Japanese oil imports.

The Netherlands and Britain followed suit. With oil reserves that would

last only a year and a half during peacetime (much less during wartime),

this ABCD line left Japan two choices: comply with the U.S.-led demand to pull out of China, or seize the oilfields in the East Indies from the Netherlands. The Japanese government deemed it unacceptable to retreat from China.

The Mason-Overy Debate: "The Flight into War" theory

In the late 1980s, the British historian Richard Overy was involved in a historical dispute with Timothy Mason that mostly played out over the pages of the Past and Present journal over the reasons for the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Mason had contended that a "flight into war" had been imposed on Adolf Hitler

by a structural economic crisis, which confronted Hitler with the

choice of making difficult economic decisions or aggression. Overy

argued against Mason's thesis, maintaining that though Germany was faced

with economic problems in 1939, the extent of these problems cannot

explain aggression against Poland and the reasons for the outbreak of war were due to the choices made by the Nazi leadership.

Mason had argued that the German working-class was always to the

Nazi dictatorship; that in the over-heated German economy of the late

1930s, German workers could force employers to grant higher wages by

leaving for another firm that would grant the desired wage increases;

that this was a form of political resistance and this resistance forced Adolf Hitler to go to war in 1939. Thus, the outbreak of the Second World War was caused by structural economic problems, a "flight into war" imposed by a domestic crisis.

The key aspects of the crisis were according to Mason, a shaky economic

recovery was threatened by a rearmament program that was overwhelming

the economy and in which the Nazi regime's nationalist bluster limited

its options. In this way, Mason articulated a Primat der Innenpolitik ("primacy of domestic politics") view of World War II's origins through the concept of social imperialism. Mason's Primat der Innenpolitik thesis was in marked contrast to the Primat der Außenpolitik ("primacy of foreign politics) usually used to explain World War II.

In Mason's opinion, German foreign policy was driven by domestic

political considerations, and the launch of World War II in 1939 was

best understood as a "barbaric variant of social imperialism".

Mason argued that "Nazi Germany was always bent at some time upon a major war of expansion."

However, Mason argued that the timing of such a war was determined by

domestic political pressures, especially as relating to a failing

economy, and had nothing to do with what Hitler wanted.

In Mason's view in the period between 1936–41, it was the state of the

German economy, and not Hitler's 'will' or 'intentions' that was the

most important determinate on German decision-making on foreign policy.

Mason argued that the Nazi leaders were deeply haunted by the November

Revolution of 1918, and was most unwilling to see any fall in working

class living standards out of the fear that it might provoke another

November Revolution.

According to Mason, by 1939, the "overheating" of the German economy

caused by rearmament, the failure of various rearmament plans produced

by the shortages of skilled workers, industrial unrest caused by the

breakdown of German social policies, and the sharp drop in living

standards for the German working class forced Hitler into going to war

at a time and place not of his choosing.

Mason contended that when faced with the deep socio-economic crisis the

Nazi leadership had decided to embark upon a ruthless 'smash and grab'

foreign policy of seizing territory in Eastern Europe which could be

pitilessly plundered to support living standards in Germany. Mason described German foreign policy as driven by an opportunistic 'next victim' syndrome after the Anschluss, in which the "promiscuity of aggressive intentions" was nurtured by every successful foreign policy move. In Mason's opinion, the decision to sign the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact

with the Soviet Union and to attack Poland and the running of the risk

of a war with Britain and France were the abandonment by Hitler of his

foreign policy program outlined in Mein Kampf forced on him by his need to stop a collapsing German economy by seizing territory abroad to be plundered.

For Overy, the problem with Mason's thesis was that it rested on

the assumption that in a way not shown by records, information was

passed on to Hitler about the Reich's economic problems. Overy argued that there was a difference between economic pressures induced by the problems of the Four Year Plan

and economic motives to seize raw materials, industry and foreign

reserves of neighboring states as a way of accelerating the Four Year

Plan. Overy asserted that Mason downplayed the repressive capacity of the German state as a way of dealing with domestic unhappiness.

Finally, Overy argued that there is considerable evidence that the

German state felt they could master the economic problems of rearmament;

as one civil servant put it in January 1940 "we have already mastered

so many difficulties in the past, that here too, if one or other raw

material became extremely scarce, ways and means will always yet be

found to get out of a fix".

Proximate causes

Nazi dictatorship

Adolf Hitler in Bad Godesberg, Germany, 1938

Hitler and his Nazis took full control of Germany in 1933–34 (Machtergreifung), turning it into a dictatorship with a highly hostile outlook toward the Treaty of Versailles and Jews. It solved its unemployment crisis by heavy military spending.

Hitler's diplomatic tactics were to make seemingly reasonable

demands, then threatening war if they were not met; concessions were

made, he accepted them and moved onto a new demand.

When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were

offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked

as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations (1933), rejected the

Versailles Treaty and began to re-arm with the Anglo-German Naval Agreement

(1935), won back the Saar (1935), re-militarized the Rhineland (1936),

formed an alliance ("axis") with Mussolini's Italy (1936), sent massive

military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), seized

Austria (1938), took over Czechoslovakia after the British and French

appeasement of the Munich Agreement of 1938, formed a peace pact with

Stalin's Russia in August 1939 – and finally invaded Poland in September

1939.

Re-militarization of the Rhineland

In violation of the Treaty of Versailles and the spirit of the Locarno Pact and the Stresa Front, Germany re-militarized the Rhineland

on March 7, 1936. It moved German troops into the part of western

Germany where, according to the Versailles Treaty, they were not

allowed. France could not act because of political instability at the

time. King Edward VIII, who thought the Versailles provision was unjust, ordered the government to stand down.

Italian invasion of Ethiopia (Abyssinia)

After the Stresa Conference and even as a reaction to the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini attempted to expand the Italian Empire in Africa by invading the Ethiopian Empire (also known as Abyssinia). The League of Nations

declared Italy the aggressor and imposed sanctions on oil sales that

proved ineffective. Italy annexed Ethiopia on May 7 and merged Ethiopia,

Eritrea, and Somaliland into a single colony known as Italian East Africa. On June 30, 1936, Emperor Haile Selassie

gave a stirring speech before the League of Nations denouncing Italy's

actions and criticizing the world community for standing by. He warned

that "It is us today. It will be you tomorrow". As a result of the

League's condemnation of Italy, Mussolini declared the country's

withdrawal from the organization.

Spanish Civil War

Francisco Franco and Heinrich Himmler in Madrid, Spain, 1940

Between 1936 and 1939, Germany and Italy lent support to the Nationalists led by general Francisco Franco in Spain, while the Soviet Union supported the existing democratically elected government, the Spanish Republic,

led by Manuel Azaña. Both sides experimented with new weapons and

tactics. The League of Nations was never involved, and the major powers

of the League remained neutral and tried (with little success) to stop

arms shipments into Spain. The Nationalists eventually defeated the

Republicans in 1939.

Spain negotiated with joining the Axis but remained neutral during World War II, and did business with both sides. It also sent a volunteer unit

to help the Germans against the USSR. Whilst it was considered in the

1940s and 1950s to be a prelude to World War II and It prefigured the

war to some extent (as it changed it into an antifascists contest after

1941), it bore no resemblance to the war that started in 1939 and had no

major role in causing it.

Second Sino-Japanese War

In 1931 Japan took advantage of China's weakness in the Warlord Era and fabricated the Mukden Incident in 1931 to set up the puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria, with Puyi, who had been the last emperor of China, as its emperor. In 1937 the Marco Polo Bridge Incident triggered the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The invasion was launched by the bombing of many cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Guangzhou.

The latest, which began on 22 and 23 September 1937, called forth

widespread protests culminating in a resolution by the Far Eastern

Advisory Committee of the League of Nations. The Imperial Japanese Army captured the Chinese capital city of Nanjing, and committed war crimes in the Nanjing massacre.

The war tied down large numbers of Chinese soldiers, so Japan set up

three different Chinese puppet states to enlist some Chinese support.

Anschluss

Cheering crowds greet the Nazis in Innsbruck

The Anschluss was the 1938 annexation by threat of force of Austria into Germany. Historically, the Pan-Germanism idea of creating a Greater Germany to include all ethnic Germans into one nation-state was popular for Germans in both Austria and Germany.

1937 ethno-linguistic situation in central Europe

One of the Nazi party's

points was "We demand the unification of all Germans in the Greater

Germany on the basis of the people's right to self-determination."

The Stresa Front of 1935 between Britain, France and Italy had guaranteed the independence of Austria, but after the creation of the Rome-Berlin Axis Mussolini was much less interested in upholding its independence.

The Austrian government resisted as long as possible, but had no

outside support and finally gave in to Hitler's fiery demands. No

fighting occurred as most Austrians were enthusiastic, and Austria was

fully absorbed as part of Germany. Outside powers did nothing. Italy had

little reason for continued opposition to Germany, and was if anything

drawn in closer to the Nazis.

Munich Agreement

The Sudetenland was a predominantly German region inside Czechoslovakia

alongside its border with Germany. Its more than three million ethnic

Germans comprised almost a quarter of the population of Czechoslovakia.

In the Treaty of Versailles

it was given to the new Czechoslovak state against the wishes of much

of the local population. The decision to disregard their right to self determination was based on French intent to weaken Germany. Much of Sudetenland was industrialized.

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Hitler at a meeting in Germany on 24 September 1938, where Hitler demanded annexation of Czech border areas without delay

Czechoslovakia had a modern army of 38 divisions, backed by a well-noted armament industry (Škoda)

as well as military alliances with France and the Soviet Union. However

its defensive strategy against Germany was based on the mountains of

the Sudetenland.

Hitler pressed for the Sudetenland's incorporation into the

Reich, supporting German separatist groups within the Sudeten region.

Alleged Czech brutality and persecution under Prague helped to stir up

nationalist tendencies, as did the Nazi press. After the Anschluss, all

German parties (except the German Social-Democratic party) merged with

the Sudeten German Party

(SdP). Paramilitary activity and extremist violence peaked during this

period and the Czechoslovakian government declared martial law in parts

of the Sudetenland to maintain order. This only complicated the

situation, especially now that Slovakian nationalism was rising, out of

suspicion towards Prague and Nazi encouragement. Citing the need to

protect the Germans in Czechoslovakia, Germany requested the immediate

annexation of the Sudetenland.

In the Munich Agreement

of September 30, 1938, British, French and Italian prime ministers

appeased Hitler by giving him what he wanted, hoping he would not want

any more. The conferring powers allowed Germany to move troops into the

region and incorporate it into the Reich "for the sake of peace." In

exchange for this, Hitler gave his word that Germany would make no

further territorial claims in Europe.

Czechoslovakia was not allowed to participate in the conference. When

the French and British negotiators informed the Czechoslovak

representatives about the agreement, and that if Czechoslovakia would

not accept it, France and Britain would consider Czechoslovakia to be

responsible for war, President Edvard Beneš capitulated. Germany took the Sudetenland unopposed.

Chamberlain's policies have been the subject of intense debate

for more than seventy years among academics, politicians, and diplomats.

The historians' assessments have ranged from condemnation for allowing

Hitler's Germany to grow too strong, to the judgment that Germany was so

strong that it might well win a war and that postponement of a

showdown was in their country's best interests.

German occupation and Slovak independence

All territories taken from Czechoslovakia by its neighbours in October 1938 ("Munich Dictate") and March 1939

In March 1939, breaking the Munich Agreement, German troops invaded

Prague, and with the Slovaks declaring independence, the country of

Czechoslovakia disappeared. The entire ordeal was the last show of the

French and British policy of appeasement.

Italian invasion of Albania

After the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, Benito Mussolini

feared for Italy becoming a second-rate member of the Axis. Rome

delivered Tirana an ultimatum on March 25, 1939, demanding that it

accede to Italy's occupation of Albania. King Zog

refused to accept money in exchange for countenancing a full Italian

takeover and colonization of Albania. On April 7, 1939, Italian troops

invaded Albania. Albania was occupied after a 3 days campaign with

minimal resistance offered by the Albanian forces.

Soviet–Japanese Border War

In 1939, the Japanese attacked west from Manchuria into the Mongolian People's Republic, following the earlier Battle of Lake Khasan in 1938. They were decisively beaten by Soviet units under General Georgy Zhukov.

Following this battle, the Soviet Union and Japan were at peace until

1945. Japan looked south to expand its empire, leading to conflict with

the United States over the Philippines and control of shipping lanes to

the Dutch East Indies. The Soviet Union focused on her western border,

but leaving 1 million to 1.5 million troops to guard the frontier with

Japan.

Danzig crisis

The Polish Corridor and the Free City of Danzig

After the final fate of Czechoslovakia proved that the Führer's word

could not be trusted, Britain and France decided on a change of

strategy. They decided any further unilateral German expansion would be

met by force. The natural next target for the Third Reich's further

expansion was Poland, whose access to the Baltic sea had been carved out of West Prussia by the Versailles treaty, making East Prussia an exclave. The main port of the area, Danzig, had been made a free city-state under Polish influence guaranteed by the League of Nations, a stark reminder to German nationalists of the Napoleonic free city established after the French emperor's crushing victory over Prussia in 1807.

After taking power, the Nazi government made efforts to establish

friendly relations with Poland, resulting in the signing of the

ten-year German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact with the Piłsudski regime in 1934. In 1938, Poland participated in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia by annexing Zaolzie. In 1939, Hitler claimed extraterritoriality for the Reichsautobahn Berlin-Königsberg

and a change in Danzig's status, in exchange for promises of territory

in Poland's neighbours and a 25-year extension of the non-aggression

pact. Poland refused, fearing losing de facto access to the sea,

subjugation as a German satellite state or client state, and future further German demands.[56][57] In August 1939, Hitler delivered an ultimatum to Poland on Danzig's status.

Polish alliance with the Entente

In March 1939, Britain and France guaranteed the independence of

Poland. Hitler's claims in the summer of 1939 on Danzig and the Polish

Corridor provoked yet another international crisis. On August 25, Britain signed the Polish-British Common Defence Pact.

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

Nominally, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression treaty between Germany and the Soviet Union. It was signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939, by the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.

In 1939, neither Germany nor the Soviet Union were ready to go to

war with each other. The Soviet Union had lost territory to Poland in

1920. Although officially labeled a "non-aggression treaty", the pact

included a secret protocol, in which the independent countries of

Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania were divided

into spheres of interest of the parties. The secret protocol explicitly assumed "territorial and political rearrangements" in the areas of these countries.

Subsequently, all the mentioned countries were invaded, occupied,

or forced to cede part of their territory by either the Soviet Union,

Germany, or both.

Declarations of war

Invasion of Poland

Germany invaded Poland

on 1 September 1939 which directly led to the Anglo-French declaration

of war on Germany on 3 Sept. The Soviet Union joined Germany's invasion

of Poland on 17 September.

Between 1919 and 1939 Poland pursued a policy of balancing between

the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, seeking non-aggression treaties with

both. In early 1939 Germany demanded that Poland join the Anti-Comintern Pact as a satellite state of Germany.

Poland, fearing a loss of independence, refused, and Hitler told his

generals on 23 May 1939 that the reason for invading Poland was not

Danzig: "Danzig is not the issue at stake. It's a matter of extending

our living space in the East..."

To deter Hitler, Britain and France announced that an invasion would

mean war and tried to convince the Soviet Union to join in this

deterrence. The USSR, however, gained control of the Baltic states and

parts of Poland by allying with Germany, which it did through the secret

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

in August 1939. London's attempt at deterrence failed, but Hitler did

not expect a wider war. Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and

rejected the British and French demands that it withdraw, resulting in

their declaration of war on September 3, 1939, in accordance with the

defense treaties with Poland that they had signed and publicly

announced.

Invasion of the Soviet Union

Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. Hitler believed that

the Soviet Union could be defeated in a fast-paced and relentless

assault that capitalized on the Soviet Union's ill-prepared state, and

hoped that success there would bring Britain to the negotiation table,

ending the war altogether.

Attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, British Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong

The US government and the American public in general had been supportive of China, condemning the colonialist policies of the European powers and Japan, and promoting a so-called Open Door Policy. Many Americans viewed the Japanese as an aggressive and/or inferior race. The Nationalist Government of Chiang Kai-shek held friendly relations with the United States, which opposed Japan's invasion of China in 1937 that it considered an illegal violation of the sovereignty of the Republic of China,

and offered the Nationalist Government diplomatic, economic, and

military assistance during its war against Japan. Diplomatic friction

between the US and Japan manifested itself in events like the Panay incident in 1937 and the Allison incident in 1938.

Japanese troops entering Saigon

Reacting to Japanese pressure on French authorities of French Indochina

to stop trade with China, the U.S. began restricting trade with Japan

in July 1940. The cutoff of all oil shipments in 1941 was decisive, for

the U.S., Britain and the Netherlands provided almost all of Japan's

oil. In September 1940, the Japanese invaded Vichy French Indochina and occupied Tonkin in order to prevent China from importing arms and fuel through French Indochina along the Sino-Vietnamese Railway, from the port of Haiphong through Hanoi to Kunming in Yunnan. The U.S.decided the Japanese had now gone too far and decided to force a roll-back of its gains.

In 1940–41, the U.S. and China decided to organize a volunteer squadron

of American planes and pilots to attack Japan from Chinese bases. Known

as the Flying Tigers, the unit was commanded by Claire Lee Chennault. Their first combat came two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Taking advantage of the situation, Thailand launched the Franco-Thai War

in October 1940. Japan stepped in as a mediator for the Frenco-Thai

war in May 1941, allowing its ally to occupy bordering provinces in Cambodia and Laos.

In July 1941, as operation Barbarossa had effectively neutralized the

Soviet threat, the faction of the Japanese military junta supporting the

"Southern Strategy", pushed through the occupation of the rest of

French Indochina.

The United States reacted by seeking to bring the Japanese war effort to a complete halt by imposing a full embargo

on all trade between the United States to Japan on 1 August 1941,

demanding that Japan withdraw all troops from both China and Indochina.

Japan was dependent on the United States for 80 percent of its oil,

resulting in an economic and military crisis for Japan that could not

continue its war effort with China without access to petroleum and oil

products.

Attack on Pearl Harbor, December 1941

On 7 December 1941, without any prior declaration of war, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor with the aim of destroying the main American battle fleet at anchor. At the same time, other Japanese forces attacked the U.S.-held Philippines and the British Empire in Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

The following day, an official Japanese declaration of war on the

United States and the British Empire was printed on the front page of

all Japanese newspapers' evening editions.

Due to international time differences, this announcement took place

between midnight and 3 a.m. on 8 December in North America, and at about

8 a.m. on 8 December in the UK.

Canada declared war on Japan on the evening of 7 December; a royal proclamation affirmed the declaration the next day. The United Kingdom declared war on Japan

on the morning of 8 December, specifically identifying the attacks on

Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong as the cause, and omitting any mention

of Pearl Harbor. The United States declared war upon Japan

on the afternoon of 8 December, some nine hours after the UK,

identifying only "unprovoked acts of war against the Government and the

people of the United States of America" as the cause.

Four days later the U.S was brought into the European war when on December 11, 1941, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy declared war on the United States. Hitler chose to declare that the Tripartite Pact

required that Germany follow Japan's declaration of war; although

American destroyers escorting convoys and German U-boats were already de

facto at war in the Battle of the Atlantic. This declaration effectively ended isolationist sentiment in the U.S. and the United States immediately reciprocated, formally entering the war in Europe.