Crowd gathering on Wall Street after the 1929 crash

| |

| Date | 4 September 1929–13 November 1929 |

|---|---|

| Type | Stock market crash |

| Cause | Fears of excessive speculation by the Federal Reserve |

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major stock market crash that occurred in 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange collapsed.

It was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, when taking into consideration the full extent and duration of its aftereffects. The crash, which followed the London Stock Exchange's crash of September, signaled the beginning of the Great Depression.

Background

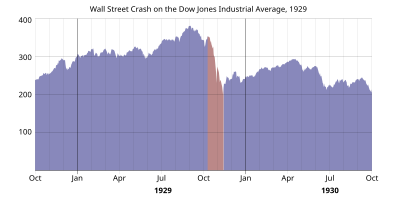

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, 1928–1930

The "Roaring Twenties", the decade following World War I that led to the crash,

was a time of wealth and excess. Building on post-war optimism, rural

Americans migrated to the cities in vast numbers throughout the decade

with the hopes of finding a more prosperous life in the ever-growing

expansion of America's industrial sector. While American cities prospered, however, the overproduction of agricultural produce created widespread financial despair among American farmers throughout the decade, which was later blamed as one of the key factors that led to the 1929 stock market crash.

Despite the dangers of speculation, it was widely believed that the stock market would continue to rise forever: on March 25, 1929, after the Federal Reserve

warned of excessive speculation, a small crash occurred as investors

started to sell stocks at a rapid pace, exposing the market's shaky

foundation. Two days later, banker Charles E. Mitchell announced that his company, the National City Bank, would provide $25 million in credit to stop the market's slide. Mitchell's move brought a temporary halt to the financial crisis, and call money declined from 20 to 8 percent. However, the American economy showed ominous signs of trouble:

steel production declined, construction was sluggish, automobile sales

went down, and consumers were building up high debts because of easy

credit.

Despite all the economic warning signs and the market breaks in

March and May 1929, stocks resumed their advance in June and the gains

continued almost unabated until early September 1929 (the Dow Jones

average gained more than 20% between June and September). The market had

been on a nine-year run that saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average increase in value tenfold, peaking at 381.17 on September 3, 1929. Shortly before the crash, economist Irving Fisher famously proclaimed "Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau." The optimism and the financial gains of the great bull market were shaken after a well-publicized early September prediction from financial expert Roger Babson that "a crash is coming, and it may be terrific".[7]

The initial September decline was thus called the "Babson Break" in the

press. That was the start of the Great Crash, but until the severe

phase of the crash in October, many investors regarded the September

"Babson Break" as a "healthy correction" and buying opportunity.

On September 20, the London Stock Exchange crashed when top British investor Clarence Hatry and many of his associates were jailed for fraud and forgery. The London crash greatly weakened the optimism of American investment in markets overseas:

in the days leading up to the crash, the market was severely unstable.

Periods of selling and high volumes were interspersed with brief periods

of rising prices and recovery.

Crash

Overall Price Indexon Wall Street from just before the crash in 1929 to 1932 when the price bottomed out

Selling

intensified in mid-October. On October 24, "Black Thursday", the market

lost 11 percent of its value at the opening bell on very heavy trading. The huge volume meant that the report of prices on the ticker tape

in brokerage offices around the nation was hours late and so investors

had no idea what most stocks were actually trading for. Several leading Wall Street bankers met to find a solution to the panic and chaos on the trading floor. The meeting included Thomas W. Lamont, acting head of Morgan Bank; Albert Wiggin, head of the Chase National Bank; and Charles E. Mitchell, president of the National City Bank of New York. They chose Richard Whitney, vice president of the Exchange, to act on their behalf.

With the bankers' financial resources behind him, Whitney placed a bid to purchase a large block of shares in U.S. Steel at a price well above the current market. As traders watched, Whitney then placed similar bids on other "blue chip" stocks. The tactic was similar to one that had ended the Panic of 1907,

and succeeded in halting the slide. The Dow Jones Industrial Average

recovered, closing with it down only 6.38 points for the day.

The trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange in 1930, six months after the crash of 1929

On October 28, "Black Monday," more investors facing margin calls decided to get out of the market, and the slide continued with a record loss in the Dow for the day of 38.33 points, or 12.82%.

The next day, the panic selling reached its peak with some stocks having no buyers at any price. The Dow lost an additional 30.57 points, or 11.73%, for a total drop of 23% in two days.

On October 29, William C. Durant joined with members of the Rockefeller family

and other financial giants to buy large quantities of stocks to

demonstrate to the public their confidence in the market, but their

efforts failed to stop the large decline in prices. The massive volume

of stocks traded that day made the ticker continue to run until about 7:45 p.m.

| Date | Change | % Change | Close |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 28, 1929 | −38.33 | −12.82 | 260.64 |

| October 29, 1929 | −30.57 | −11.73 | 230.07 |

After a one-day recovery on October 30, when the Dow regained 28.40

points, or 12.34%, to close at 258.47, the market continued to fall,

arriving at an interim bottom on November 13, 1929, with the Dow closing

at 198.60. The market then recovered for several months, starting on

November 14, with the Dow gaining 18.59 points to close at 217.28, and

reaching a secondary closing peak (bear market

rally) of 294.07 on April 17, 1930. The Dow then embarked on another,

much longer, steady slide from April 1930 to July 8, 1932, when it

closed at 41.22, its lowest level of the 20th century, concluding an

89.2% loss for the index in less than three years.

Beginning on March 15, 1933, and continuing through the rest of

the 1930s, the Dow began to slowly regain the ground it had lost. The

largest percentage increases of the Dow Jones occurred during the early

and mid-1930s. In late 1937, there was a sharp dip in the stock market,

but prices held well above the 1932 lows. The Dow Jones did not return

to the peak closing of September 3, 1929, until November 23, 1954.

Aftermath

In 1932, the Pecora Commission was established by the U.S. Senate to study the causes of the crash. The following year, the U.S. Congress passed the Glass–Steagall Act mandating a separation between commercial banks, which take deposits and extend loans, and investment banks, which underwrite, issue, and distribute stocks, bonds, and other securities.

After the experience of the 1929 crash, stock markets around the

world instituted measures to suspend trading in the event of rapid

declines, claiming that the measures would prevent such panic sales.

However, the one-day crash of Black Monday, October 19, 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 22.6%, as well as Black Monday of March 16, 2020

(-12.9%), were worse in percentage terms than any single day of the

1929 crash (although the combined 25% decline of October 28–29, 1929 was

larger than that of October 19, 1987, and remains the worst two-day

decline ever).

World War II

The American mobilization for World War II at the end of 1941 moved approximately ten million people out of the civilian labor force and into the war.

World War II had a dramatic effect on many parts of the economy, and

may have hastened the end of the Great Depression in the United States.

Government-financed capital spending accounted for only 5 percent of

the annual U.S. investment in industrial capital in 1940; by 1943, the

government accounted for 67 percent of U.S. capital investment.

Analysis

The crash followed a speculative

boom that had taken hold in the late 1920s. During the latter half of

the 1920s, steel production, building construction, retail turnover,

automobiles registered, and even railway receipts advanced from record

to record. The combined net profits of 536 manufacturing and trading

companies showed an increase, in the first six months of 1929, of 36.6%

over 1928, itself a record half-year. Iron and steel led the way with

doubled gains.

Such figures set up a crescendo of stock-exchange speculation that led

hundreds of thousands of Americans to invest heavily in the stock

market. A significant number of them were borrowing money

to buy more stocks. By August 1929, brokers were routinely lending

small investors more than two-thirds of the face value of the stocks

they were buying. Over $8.5 billion was out on loan, more than the entire amount of currency circulating in the U.S. at the time.

The rising share prices encouraged more people to invest, hoping

the share prices would rise further. Speculation thus fueled further

rises and created an economic bubble. Because of margin buying, investors stood to lose large sums of money if the market turned down—or even failed to advance quickly enough. The average price to earnings ratio of S&P Composite stocks was 32.6 in September 1929, clearly above historical norms. According to economist John Kenneth Galbraith,

this exuberance also resulted in a large number of people placing their

savings and money in leverage investment products like Goldman Sachs'

"Blue Ridge trust" and "Shenandoah trust". These too crashed in 1929,

resulting in losses to banks of $475 billion 2010 dollars

($556.91 billion in 2019).

Sir George Paish

Good harvests had built up a mass of 250 million bushels of wheat to

be "carried over" when 1929 opened. By May there was also a winter-wheat

crop of 560 million bushels ready for harvest in the Mississippi

Valley. This oversupply caused a drop in wheat prices so heavy that the

net incomes of the farming population from wheat were threatened with

extinction. Stock markets are always sensitive to the future state of

commodity markets, and the slump in Wall Street predicted for May by Sir George Paish

arrived on time. In June 1929, the position was saved by a severe

drought in the Dakotas and the Canadian West, plus unfavorable seed

times in Argentina and eastern Australia. The oversupply was now wanted

to fill the gaps in the 1929 world wheat production. From 97¢ per bushel

in May, the price of wheat rose to $1.49 in July. When it was seen that

at this figure American farmers would get more for their crop than for

that of 1928, stocks went up again.

In August, the wheat price fell when France and Italy were

bragging of a magnificent harvest, and the situation in Australia

improved. That sent a shiver through Wall Street and stock prices

quickly dropped, but word of cheap stocks brought a fresh rush of

"stags", amateur speculators and investors. Congress voted for a $100

million relief package for the farmers, hoping to stabilize wheat

prices. By October though, the price had fallen to $1.31 per bushel.

Other important economic barometers were also slowing or even

falling by mid-1929, including car sales, house sales, and steel

production. The falling commodity and industrial production may have

dented even American self-confidence, and the stock market peaked on

September 3 at 381.17 just after Labor Day, then started to falter after

Roger Babson

issued his prescient "market crash" forecast. By the end of September,

the market was down 10% from the peak (the "Babson Break"). Selling

intensified in early and mid October, with sharp down days punctuated by

a few up days. Panic selling

on huge volume started the week of October 21 and intensified and

culminated on October 24, the 28th, and especially the 29th ("Black

Tuesday").

The president of the Chase National Bank, Albert H. Wiggin, said at the time:

We are reaping the natural fruit of the orgy of speculation in which millions of people have indulged. It was inevitable, because of the tremendous increase in the number of stockholders in recent years, that the number of sellers would be greater than ever when the boom ended and selling took the place of buying."

Effects

United States

Crowd at New York's American Union Bank during a bank run early in the Great Depression

Together, the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression formed the largest financial crisis of the 20th century.

The panic of October 1929 has come to serve as a symbol of the economic

contraction that gripped the world during the next decade. The falls in share prices on October 24 and 29, 1929 were practically instantaneous in all financial markets, except Japan.

The Wall Street Crash had a major impact on the U.S. and world

economy, and it has been the source of intense academic historical,

economic, and political debate from its aftermath until the present day.

Some people believed that abuses by utility holding companies

contributed to the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Depression that

followed. Many people blamed the crash on commercial banks that were too eager to put deposits at risk on the stock market.

In 1930, 1,352 banks held more than $853 million in deposits; in

1931, one year later, 2,294 banks went down with nearly $1.7 billion in

deposits. Many businesses failed (28,285 failures and a daily rate of

133 in 1931).

The 1929 crash brought the Roaring Twenties to a halt. As tentatively expressed by economic historian Charles P. Kindleberger, in 1929, there was no lender of last resort

effectively present, which, if it had existed and been properly

exercised, would have been key in shortening the business slowdown that

normally follows financial crises.

The crash instigated widespread and long-lasting consequences for the

United States. Historians still debate whether the 1929 crash sparked

the Great Depression

or if it merely coincided with the bursting of a loose credit-inspired

economic bubble. Only 16% of American households were invested in the

stock market within the United States during the period leading up to

this depression, suggesting that the crash carried somewhat less of a

weight in causing it.

Unemployed men march in Toronto

However, the psychological effects of the crash reverberated across

the nation as businesses became aware of the difficulties in securing

capital market investments for new projects and expansions. Business

uncertainty naturally affects job security for employees, and as the

American worker (the consumer) faced uncertainty with regards to income,

naturally the propensity to consume declined. The decline in stock

prices caused bankruptcies and severe macroeconomic

difficulties, including contraction of credit, business closures,

firing of workers, bank failures, decline of the money supply, and other

economically depressing events.

The resultant rise of mass unemployment is seen as a result of

the crash, although the crash is by no means the sole event that

contributed to the depression. The Wall Street Crash is usually seen as

having the greatest impact on the events that followed and therefore is

widely regarded as signaling the downward economic slide that initiated

the Great Depression. True or not, the consequences were dire for almost

everybody. Most academic experts agree on one aspect of the crash: It

wiped out billions of dollars of wealth in one day, and this immediately

depressed consumer buying.

The failure set off a worldwide run on US gold deposits (i.e. the

dollar), and forced the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates into

the slump. Some 4,000 banks and other lenders ultimately failed. Also,

the uptick rule,

which allowed short selling only when the last tick in a stock's price

was positive, was implemented after the 1929 market crash to prevent

short sellers from driving the price of a stock down in a bear raid.

Europe

The stock market crash of October 1929 led directly to the Great Depression in Europe. When stocks plummeted on the New York Stock Exchange,

the world noticed immediately. Although financial leaders in the United

Kingdom, as in the United States, vastly underestimated the extent of

the crisis that ensued, it soon became clear that the world's economies

were more interconnected than ever. The effects of the disruption to the

global system of financing, trade, and production and the subsequent

meltdown of the American economy were soon felt throughout Europe.

In 1930 and 1931, in particular, unemployed workers went on

strike, demonstrated in public, and otherwise took direct action to call

public attention to their plight. Within the UK, protests often focused

on the so-called Means Test,

which the government had instituted in 1931 to limit the amount of

unemployment payments made to individuals and families. For working

people, the Means Test seemed an intrusive and insensitive way to deal

with the chronic and relentless deprivation caused by the economic

crisis. The strikes were met forcefully, with police breaking up

protests, arresting demonstrators, and charging them with crimes related

to the violation of public order.

Academic debate

There is ongoing debate among economists and historians as to what

role the crash played in subsequent economic, social, and political

events. The Economist argued in a 1998 article that the Depression did not start with the stock market crash,

nor was it clear at the time of the crash that a depression was

starting. They asked, "Can a very serious Stock Exchange collapse

produce a serious setback to industry when industrial production is for

the most part in a healthy and balanced condition?" They argued that

there must be some setback, but there was not yet sufficient evidence to

prove that it would be long or would necessarily produce a general

industrial depression.

However, The Economist also cautioned that some bank

failures were also to be expected and some banks may not have had any

reserves left for financing commercial and industrial enterprises. It

concluded that the position of the banks was the key to the situation,

but what was going to happen could not have been foreseen.

Some academics view the Wall Street Crash of 1929 as part of a historical process that was a part of the new theories of boom and bust. According to economists such as Joseph Schumpeter, Nikolai Kondratiev and Charles E. Mitchell, the crash was merely a historical event in the continuing process known as economic cycles. The impact of the crash was merely to increase the speed at which the cycle proceeded to its next level.

Milton Friedman's A Monetary History of the United States, co-written with Anna Schwartz, argues that what made the "great contraction" so severe was not the downturn in the business cycle, protectionism,

or the 1929 stock market crash in themselves but the collapse of the

banking system during three waves of panics from 1930 to 1933.