Decolonization (American English) or decolonisation (British English) is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby a nation establishes and maintains its domination on overseas territories. The concept particularly applies to the dismantlement, during the second half of the 20th century, of the colonial empires established prior to World War I throughout the world. Scholars focus especially on the movements in the colonies demanding independence, such as Creole nationalism.

The fundamental right to self-determination is identified by the United Nations as core to decolonization, allowing not only independence, but also other ways of decolonization. The United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization has stated that in the process of decolonization there is no alternative to the colonizer but to allow a process of self-determination. Self-determination continues to be claimed, also within independent states, to demand decolonization, as in the case of Indigenous Peoples.

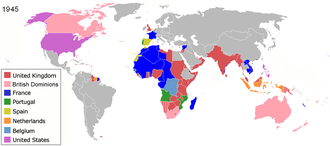

Decolonization may involve either nonviolent revolution or national liberation wars by pro-independence groups. It may be intranational or involve the intervention of foreign powers acting individually or through international bodies such as the United Nations. Although examples of decolonization can be found as early as the writings of Thucydides, there have been several particularly active periods of decolonization in modern times. These include the breakup of the Spanish Empire in the 19th century; of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires following World War I; of the British, French, Dutch, Japanese, Portuguese, Belgian and Italian colonial empires following World War II; and of the Soviet Union (successor to the Russian Empire) at the end of the Cold War in 1991.

Decolonization has been used to refer to the intellectual decolonization from the colonizers' ideas that made the colonized feel inferior.

Issues of decolonization persist and are raised contemporarily. In Latin America and South Africa such issues are increasingly discussed under the term decoloniality.

Methods and stages

Decolonization is a political process. In extreme circumstances, there is a war of independence.

More often, there is a dynamic cycle where negotiations fail, minor

disturbances ensue resulting in suppression by the police and military

forces, escalating into more violent revolts

that lead to further negotiations until independence is granted. In

rare cases, the actions of the pro-independence movements are

characterized by nonviolence, with the Indian independence movement led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

being one of the most notable examples, and the violence comes as

active suppression from the occupying forces or as political opposition

from forces representing minority local communities who feel threatened

by the prospect of independence. For example, there was a war of

independence in French Indochina, while in some countries in French West Africa (excluding the Maghreb countries) decolonization resulted from a combination of insurrection and negotiation. The process is only complete when the de facto government of the newly independent country is recognized as the de jure sovereign state by the community of nations.

Independence is often difficult to achieve without the

encouragement and practical support from one or more external parties.

The motives for giving such aid are varied: nations of the same ethnic

and/or religious stock may sympathize with the people of the country, or

a strong nation may attempt to destabilize a colony as a tactical move

to weaken a rival or enemy colonizing power or to create space for its

own sphere of influence; examples of this include British support of the Haitian Revolution against France, and the Monroe Doctrine

of 1823, in which the United States warned the European powers not to

interfere in the affairs of the newly independent states of the Western Hemisphere.

As world opinion became more pro-independence following World War I, there was an institutionalized collective effort to advance the cause of decolonization through the League of Nations. Under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, a number of mandates

were created. The expressed intention was to prepare these countries

for self-government, but the mandates are often interpreted as a mere

redistribution of control over the former colonies of the defeated

powers, mainly the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire. This reassignment work continued through the United Nations, with a similar system of trust territories created to adjust control over both former colonies and mandated territories.

Comorians protest against Mayotte referendum on becoming an overseas department of France, 2009

In referendums, some dependent territories have chosen to retain their dependent status, such as Gibraltar and French Guiana. There are even examples, such as the Falklands War,

in which a geopolitical power goes to war to defend the right of a

dependent territory to continue to be such. Colonial powers have

sometimes promoted decolonization in order to shed the financial,

military and other burdens that tend to grow in those colonies where the

colonial governments have become more benign.

Decolonization is rarely achieved through a single historical

act, but rather progresses through one or more stages of decolonization,

each of which can be offered or fought for: these can include the

introduction of elected representatives (advisory or voting; minority or

majority or even exclusive), degrees of autonomy or self-rule. Thus,

the final phase of decolonization may, in fact, concern little more than

handing over responsibility for foreign relations and security, and

soliciting de jure recognition for the new sovereignty.

But, even following the recognition of statehood, a degree of

continuity can be maintained through bilateral treaties between now

equal governments involving practicalities such as military training,

mutual protection pacts, or even a garrison and/or military bases.

The economic reforms taking place in the Europe and the building

of the welfare state – in Britain to be specific, led to the withdrawal

of the colonial powers from the overseas territories.The British public

had other priorities after 1945, the war-weary and bankrupt imperial

power had aimed to somehow finance a new welfare state; the British

public had little enthusiasm for sending troops and money to hold onto

overseas territories against their will.

History

Beginning with the emergence of the United States in the 1770s, decolonization took place in the context of Atlantic history,

against the background of the American and French revolutions.

Decolonization became a wider movement in many colonies in the 20th

century, and a reality after 1945.

The historian William Hardy McNeill, in his famous 1963 book The Rise of the West, appears to have interpreted the post-1945 decline of European empires as paradoxically being due to Westernization itself, writing that

Although European empires have decayed since 1945, and the separate nation-states of Europe have been eclipsed as centres of political power by the melding of peoples and nations occurring under the aegis of both the American and Russian governments, it remains true that, since the end of World War II, the scramble to imitate and appropriate science, technology, and other aspects of Western culture has accelerated enormously all round the world. Thus the dethronement of western Europe from its brief mastery of the globe coincided with (and was caused by) an unprecedented, rapid Westernization of all the peoples of the earth.

In the same book, McNeill wrote that "The rise of the West, as

intended by the title and meaning of this book, is only accelerated when

one or another Asian or African people throws off European

administration by making Western techniques, attitudes, and ideas

sufficiently their own to permit them to do so".

American Revolution

Great Britain's Thirteen North American colonies

were the first colonies to break from their colonial motherland by

declaring independence as the United States of America in 1776, and

being recognized as an independent nation by France in 1778 and Britain

in 1783.

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution was a slave uprising that began in 1791 in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. In 1804, Haiti secured independence from France as the Empire of Haiti, which later became a republic.

Spanish America

The Chilean Declaration of Independence on 18 February 1818

The chaos of the Napoleonic wars in Europe cut the direct links between Spain and its American colonies, allowing for process of decolonization to begin.

With the invasion of Spain by Napoleon in 1806, the American

colonies declared autonomy and loyalty to King Ferdinand VII. The

contract was broken and the regions of the Spanish Empire had to decide

whether to show allegiance to the Junta of Cadiz (the only territory in

Spain free from Napoleon) or have a junta (assembly) of its own. The

economic monopoly of the metropolis was the main reason why many

countries decided to become independent from Spain. In 1809, the

independence wars of Latin America began with a revolt in La Paz,

Bolivia. In 1807 and 1808, the Viceroyalty of the River Plate

was invaded by the British. After their 2nd defeat, a Frenchman called

Santiague de Liniers was proclaimed new Viceroy by the local population

and later accepted by Spain. In May 1810 in Buenos Aires, a Junta was created, but in Montevideo

it was not recognized by the local government who followed the

authority of the Junta of Cadiz. The rivalry between the two cities was

the main reason for the distrust between them. During the next 15 years,

the Spanish and Royalist on one side, and the rebels on the other

fought in South America and Mexico. Numerous countries declared their

independence. In 1824, the Spanish forces were defeated in the Battle of Ayacucho. The mainland was free, and in 1898, Spain lost Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Spanish–American War. Puerto Rico became an unincorporated territory of the US, but Cuba became independent in 1902.

Ottoman Empire

Cyprus

Cyprus was invaded and taken over by the Ottoman Empire in 1570. It was later relinquished by the Ottomans in 1878.

The Cypriots expressed their true disdain for Ottoman rule through

revolts and nationalist movements. The Ottomans only suppressed these

revolts in the harshest of fashion but that only ended up fuelling the

revolts and desire for independence.

The Cypriots desired to merge with Greece because they felt a close

connection with Greece. They were tired of 3 centuries of Turkic rule

and openly expressed their desire for enosis.

The Cypriots would embrace Greek culture and traditions. They abandoned

Ottoman architecture and showed little respect for Ottoman rule.

All these acts of defiance could be attributed to decolonization. When

the Cypriots made acts of nationalism, they were participating in a form

of decolonization because they were attempting to remove all trace of

Turkic and Muslim influence within their society. The Greek War of Independence

had major affects on Cyprus and after the Ottomans had left, Cyprus

continued to create a Greek culture they wished to be a part of. Cyprus

would continue to create this imagined identity of Greek culture. This

can also be a form of imagined human geography because Cyprus used this

identity to justify its revolts and nationalist movements.

Russian and Bulgarian defence of Shipka Pass against Turkish troops was crucial for the independence of Bulgaria.

A number of people (mainly Christians in the Balkans) previously conquered by the Ottoman Empire were able to achieve independence in the 19th century, a process that peaked at the time of the Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78.

The Ottoman Empire had failed to raise revenue and a monopoly of effective armed forces. This may have caused the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Egypt

In the wake of the 1798 French Invasion of Egypt and its subsequent expulsion in 1801, the commander of an Albanian regiment, Muhammad Ali, was able to gain control of Egypt. Although he was acknowledged by the Sultan in Constantinople in 1805 as his pasha,

Muhammad Ali, and eventually his successors, were de facto monarchs of a

largely independent state managing its own foreign relations. However,

despite this de facto independence, Egypt did remain nominally a vassal

state of the Ottoman Empire obliged to pay a hefty annual tribute to the

Sultan. Throughout the 'long 19th century', Muhammad Ali would send

scores of Azhar scholars to France and other European countries to be

educated in the empirical sciences (due to the heavy inferiority complex

ingrained from French defeat); however, such scholars would unwittingly

participate in their country's intellectual colonization throughout

this century and establish the national public educational system on

Secular Humanist (Enlightenment) philosophy and principles and Western

culture in general to this day.

Upon declaring war on Turkey in November 1914, Britain unilaterally

declared the Sultan's rights and title over Egypt abolished and proclaimed its own protectorate over the country.

Greece

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) was fought to liberate Greece from a three centuries long Ottoman occupation. Independence was secured by the intervention of the British and French navies and the French and Russian armies, but Greece was limited to an area including perhaps only one-third of ethnic Greeks, that later grew significantly with the Megali Idea project. The war ended many of the privileges of the Phanariot Greeks of Constantinople.

Bulgaria

Following a failed Bulgarian revolt in 1876, the subsequent Russo-Turkish war ended with the provisional Treaty of San Stefano established a huge new realm of Bulgaria including most of Macedonia and Thrace. The final 1878 Treaty of Berlin allowed the other Great Powers to limit the size of the new Russian client state and even briefly divided this rump state in two, Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia, but the irredentist claims from the first treaty would direct Bulgarian claims through the first and second Balkan Wars and both World Wars.

Romania

Romania fought on the Russian side in the Russo-Turkish War and in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, Romania was recognized as an independent state by the Great Powers.

Serbia

Centuries of armed and unarmed struggle ended with the recognition of Serbian independence from the Ottoman Empire at the Congress of Berlin in 1878.

Montenegro

The independence of the Principality of Montenegro from the Ottoman Empire was recognized at the congress of Berlin in 1878. However, the Montenegrin nation has been de facto independent since 1711 (officially accepted by the Tsardom of Russia by the order of Tsar Petr I Alexeyevich-Romanov. In the period 1795–1798, Montenegro once again claimed independence after the Battle of Krusi.

In 1806, it was recognized as a power fighting against Napoleon,

meaning that it had a fully mobilized and supplied army (by Russia,

through Admiral Dmitry Senyavin at the Bay of Kotor).

In the period of reign of Petar II Petrović-Njegoš, Montenegro was again colonized by Turkey, but that changed with the coming of Knyaz Danilo I, with a totally successful war against Turkey in the late 1850s ending with a decisive victory of the Montenegrin army under Grand Duke Mirko Petrović-Njegoš, brother of Danilo I, at the Battle of Grahovac.

The full independence was given to Montenegro, after almost 170 years

of fighting the Turks, Bosniaks, Albanians and the French (1806–1814) at

the Congress of Berlin.

British Empire

The emergence of indigenous political parties was especially characteristic of the British Empire,

which seemed less ruthless in controlling political dissent. Driven by

pragmatic demands of budgets and manpower the British made deals with

the local politicians. Across the empire, the general protocol was to

convene a constitutional conference in London to discuss the transition

to greater self-government and then independence, submit a report of the

constitutional conference to parliament, if approved submit a bill to

Parliament at Westminster to terminate the responsibility of the United

Kingdom (with a copy of the new constitution annexed), and finally, if

approved, issuance of an Order of Council fixing the exact date of

independence.

After World War I, several former German and Ottoman territories in the Middle East, Africa, and the Pacific were governed by the UK as League of Nations mandates. Some were administered directly by the UK, and others by British dominions – Nauru and the Territory of New Guinea by Australia, South West Africa by the Union of South Africa, and Western Samoa by New Zealand.

Egypt became independent in 1922, although the UK retained security prerogatives, control of the Suez Canal, and effective control of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. The Balfour Declaration of 1926 declared the British Empire dominions as equals, and the 1931 Statute of Westminster established full legislative independence for them. The equal dominions were six– Canada, Newfoundland, Australia, the Irish Free State, New Zealand, and the Union of South Africa;

Ireland had been an integral part of the United Kingdom until 1922 and

not a colony. However, some of the Dominions were already independent de

facto, and even de jure and recognized as such by the international

community. Thus, Canada was a founding member of the League of Nations

in 1919 and served on the Council from 1927 to 1930.

That country also negotiated on its own and signed bilateral and

multilateral treaties and conventions from the early 1900s onward.

Newfoundland ceded self-rule back to London in 1934. Iraq, a League of Nations mandate, became independent in 1932.

In response to a growing Indian independence movement, the UK made successive reforms to the British Raj, culminating in the Government of India Act (1935). These reforms included creating elected legislative councils in some of the Provinces of British India. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi,

India's independence movement leader, led a peaceful resistance to

British rule. By becoming a symbol of both peace and opposition to

British imperialism, many Indians began to view the British as the cause

of India's problems leading to a newfound sense of nationalism

among its population. With this new wave of Indian nationalism, Gandhi

was eventually able to garner the support needed to push back the

British and create an independent India in 1947.

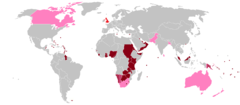

British Empire in 1952

Africa was only fully drawn into the colonial system at the end of

the 19th century. In the north-east the continued independence of the Empire of Ethiopia

remained a beacon of hope to pro-independence activists. However, with

the anti-colonial wars of the 1900s (decade) barely over, new

modernizing forms of African

Nationalism began to gain strength in the early 20th-century with the

emergence of Pan-Africanism, as advocated by the Jamaican journalist Marcus Garvey

(1887–1940) whose widely distributed newspapers demanded swift

abolition of European imperialism, as well as republicanism in Egypt. Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972) who was inspired by the works of Garvey led Ghana to independence from colonial rule.

Independence for the colonies in Africa began with the independence of Sudan in 1956, and Ghana in 1957. All of the British colonies on mainland Africa became independent by 1966, although Rhodesia's unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 was not recognized by the UK or internationally.

Some of the British colonies in Asia were directly administered

by British officials, while others were ruled by local monarchs as protectorates or in subsidiary alliance with the UK.

In 1947, British India was partitioned into the independent dominions of India and Pakistan. Hundreds of princely states, states ruled by monarchs in treaty of subsidiary alliance with Britain, were integrated into India and Pakistan. India and Pakistan fought several wars over the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. French India was integrated into India between 1950 and 1954, and India annexed Portuguese India in 1961, and the Kingdom of Sikkim in 1975.

Violence, civil warfare and partition

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781

Significant violence was involved in several prominent cases of

decolonization of the British Empire; partition was a frequent solution.

In 1783, the North American colonies were divided between the

independent United States, and British North America, which later became Canada.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857

was a revolt of a portion of the Indian Army. It was characterized by

massacres of civilians on both sides. It was not a movement for

independence, however, and only a small part of India was involved. In

the aftermath, the British pulled back from modernizing reforms of

Indian society, and the level of organised violence under the British Raj was relatively small. Most of that was initiated by repressive British administrators, as in the Amritsar massacre of 1919, or the police assaults on the Salt March of 1930.

Large-scale communicable violence broke out after the British left in

1947, turning India over to the new nations of India and Pakistan.

Cyprus, which came under full British control in 1914 from the Ottoman Empire, was culturally divided between the majority Greek element (which demanded "enosis"

or union with Greece) and the minority Turks. London for decades

assumed it needed the island to defend the Suez Canal; but after the

Suez crisis of 1956, that became a minor factor, and Greek violence

became a more serious issue. Cyprus became an independent country in

1960, but ethnic violence escalated until 1974, when Turkey invaded and

partitioned the island. Each side rewrote its own history, blaming the

other.

Palestine

became a British mandate from the League of Nations, and during the war

the British gained support from both sides by making promises both to

the Arabs and the Jews. See Balfour Declaration. Decades of ethno—religious violence resulted. The British pulled out, after dividing the Mandate into Israel and Jordan.

French Empire

After World War I, the colonized people were frustrated at France's

failure to recognize the effort provided by the French colonies

(resources, but more importantly colonial troops – the famous tirailleurs). Although in Paris the Great Mosque of Paris was constructed as recognition of these efforts, the French state had no intention to allow self-rule, let alone grant independence to the colonized people. Thus, nationalism in the colonies became stronger in between the two wars, leading to Abd el-Krim's Rif War (1921–1925) in Morocco and to the creation of Messali Hadj's Star of North Africa in Algeria in 1925. However, these movements would gain full potential only after World War II.

After World War I, France administered the former Ottoman territories of Syria and Lebanon, and the former German colonies of Togoland and Cameroon, as League of Nations mandates. Lebanon declared its independence in 1943, and Syria in 1945.

Although France was ultimately a victor of World War II, Nazi

Germany's occupation of France and its North African colonies during the

war had disrupted colonial rule. On October 27, 1946 France adopted a

new constitution creating the Fourth Republic, and substituted the French Union

for the colonial empire. However power over the colonies remained

concentrated in France, and the power of local assemblies outside France

was extremely limited. On the night of March 29, 1947, a nationalist uprising in Madagascar led the French government headed by Paul Ramadier (Socialist) to violent repression: one year of bitter fighting, 11,000–40,000 Malagasy died.

Captured French soldiers from Điện Biên Phủ, escorted by Vietnamese troops, 1954

In 1946, the states of French Indochina withdrew from the French Union, leading to the Indochina War (1946–54). Ho Chi Minh, who had been a co-founder of the French Communist Party in 1920 and had founded the Vietminh in 1941, declared independence from France, and led the armed resistance against France's reoccupation of Indochina. Cambodia and Laos became independent in 1953, and the 1954 Geneva Accords ended France's occupation of Indochina, leaving North Vietnam and South Vietnam independent.

In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia gained their independence from France. In 1960 eight independent countries emerged from French West Africa, and five from French Equatorial Africa. The Algerian War of Independence

raged from 1954 to 1962. To this day, the Algerian war – officially

called a "public order operation" until the 1990s – remains a trauma

for both France and Algeria. Philosopher Paul Ricœur has spoken of the necessity of a "decolonisation of memory", starting with the recognition of the 1961 Paris massacre during the Algerian war, and the decisive role of African and especially North African immigrant manpower in the Trente Glorieuses

post–World War II economic growth period. In the 1960s, due to economic

needs for post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth, French

employers actively sought to recruit manpower from the colonies,

explaining today's multiethnic population.

After 1918

Western European colonial powers

Czechoslovak anti-colonialist propaganda poster: "Socialism opened the door of liberation for colonial nations."

The New Imperialism period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which included the scramble for Africa and the Opium Wars,

marked the zenith of European colonization. It also accelerated the

trends that would end colonialism. The extraordinary material demands of

the conflict had spread economic change across the world (notably

inflation), and the associated social pressures of "war imperialism"

created both peasant unrest and a burgeoning middle class.

Economic growth created stakeholders with their own demands, while racial

issues meant these people clearly stood apart from the colonial

middle-class and had to form their own group. The start of mass nationalism, as a concept and practice, would fatally undermine the ideologies of imperialism.

There were, naturally, other factors, from agrarian change (and disaster – French Indochina), changes or developments in religion (Buddhism in Burma, Islam in the Dutch East Indies, marginally people like John Chilembwe in Nyasaland), and the impact of the 1930s Great Depression.

The Great Depression,

despite the concentration of its impact on the industrialized world,

was also exceptionally damaging in the rural colonies. Agricultural

prices fell much harder and faster than those of industrial goods. From

around 1925 until World War II, the colonies suffered. The colonial powers concentrated on domestic issues, protectionism and tariffs, disregarding the damage done to international trade flows. The colonies, almost all primary "cash crop"

producers, lost the majority of their export income and were forced

away from the "open" complementary colonial economies to "closed"

systems. While some areas returned to subsistence farming (British Malaya) others diversified (India, West Africa),

and some began to industrialize. These economies would not fit the

colonial straitjacket when efforts were made to renew the links.

Further, the European-owned and -run plantations proved more vulnerable to extended deflation than native capitalists, reducing the dominance of "white" farmers in colonial economies and making the European governments and investors of the 1930s co-opt indigenous

elites – despite the implications for the future. Colonial reform also

hastened their end; notably the move from non-interventionist

collaborative systems towards directed, disruptive, direct management to

drive economic change. The creation of genuine bureaucratic government

boosted the formation of indigenous bourgeoisie.

United States

A union of former colonies itself, the United States approached

imperialism differently from the other Powers. Much of its energy and

rapidly expanding population was directed westward across the North

American continent against English and French claims, the Spanish Empire and Mexico. The Native Americans were sent to reservations, often unwillingly. With support from Britain, its Monroe Doctrine

reserved the Americas as its sphere of interest, prohibiting other

states (particularly Spain) from recolonizing the newly independent

polities of Latin America.

However, France, taking advantage of the American government's

distraction during the Civil War, intervened militarily in Mexico and

set up a French-protected monarchy. Spain took the step to occupy the Dominican Republic and restore colonial rule.

The Union victory in the Civil War in 1865 forced both France and Spain

to accede to American demands to evacuate those two countries.

America's only African colony, Liberia, was formed privately and achieved independence early; Washington unofficially protected it. By 1900 the US advocated an Open Door Policy and opposed the direct division of China.

Manuel L. Quezón, the first president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines (from 1935 to 1944)

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in Micronesia administered by the United States from 1947 to 1986

After 1898 direct intervention expanded in Latin America. The United

States purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867 and annexed

Hawaii in 1898. It added most of Spain's remaining colonies in 1898–99.

Deciding not to annex Cuba outright, the U.S. established it as a client state with obligations including the perpetual lease of Guantánamo Bay

to the U.S. Navy. The attempt of the first governor to void the

island's constitution and remain in power past the end of his term

provoked a rebellion that provoked a reoccupation between 1906 and 1909,

but this was again followed by devolution. Similarly, the McKinley administration, despite prosecuting the Philippine–American War against a native republic, set out that the Territory of the Philippine Islands was eventually granted independence. In 1917, the US purchased the Danish West Indies (later renamed the US Virgin Islands) from Denmark and Puerto Ricans became full U.S. citizens that same year.

The US government declared Puerto Rico the territory was no longer a

colony and stopped transmitting information about it to the United

Nations Decolonization Committee. As a result, the UN General Assembly removed Puerto Rico from the U.N. list of non-self-governing territories.

Four referenda showed little support for independence, but much

interest in statehood such as Hawaii and Alaska received in 1959.

The Monroe Doctrine was expanded by the Roosevelt Corollary

in 1904, providing that the United States had a right and obligation to

intervene "in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence" that a

nation in the Western Hemisphere became vulnerable to European control.

In practice, this meant that the United States was led to act as a

collections agent for European creditors by administering customs duties

in the Dominican Republic (1905–1941), Haiti (1915–1934), and elsewhere. The intrusiveness and bad relations this engendered were somewhat checked by the Clark Memorandum and renounced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor Policy."

After 1947, the U.S. poured tens of billions of dollars into the Marshall Plan,

and other grants and loans to Europe and Asia to rebuild the world

economy. Washington pushed hard to accelerate decolonization and bring

an end to the colonial empires of its Western allies, most importantly

during the 1956 Suez Crisis, but American military bases were established around the world and direct and indirect interventions continued in Korea, Indochina, Latin America (inter alia, the 1965 occupation of the Dominican Republic),

Africa, and the Middle East to oppose Communist invasions and

insurgencies. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United

States has been far less active in the Americas, but invaded Afghanistan and Iraq following the September 11 attacks in 2001, establishing army and air bases in Central Asia.

Japan

U.S. troops in Korea, September 1945

Before World War I, Japan had gained several substantial colonial

possessions in East Asia such as Taiwan (1895) and Korea (1910). Japan

joined the allies in World War I, and after the war acquired the South Seas Mandate, the former German colony in Micronesia, as a League of Nations Mandate.

Pursuing a colonial policy comparable to those of European powers,

Japan settled significant populations of ethnic Japanese in its colonies

while simultaneously suppressing indigenous ethnic populations by

enforcing the learning and use of the Japanese language in schools. Other methods such as public interaction, and attempts to eradicate the use of Korean, Hokkien, and Hakka among the indigenous peoples, were seen to be used. Japan also set up the Imperial Universities in Korea (Keijō Imperial University) and Taiwan (Taihoku Imperial University) to compel education.

In 1931, Japan seized Manchuria from the Republic of China, setting up a puppet state under Puyi, the last Manchu emperor of China. In 1933 Japan seized the Chinese province of Jehol, and incorporated it into its Manchurian possessions. The Second Sino-Japanese War started in 1937, and Japan occupied much of eastern China, including the Republic's capital at Nanjing. An estimated 20 million Chinese died during the 1931–1945 war with Japan.

In December 1941, the Japanese Empire joined World War II by invading the European and US colonies in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, including French Indochina, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Burma, Malaya, Indonesia, Portuguese Timor, and others. Following its surrender to the Allies in 1945, Japan was deprived of all its colonies. The Soviet Union declared war on Japan in August 1945, and shortly after occupied and annexed the southern Kuril Islands, which Japan still claims.

Central Europe

The Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires collapsed at the end of World War I, and were replaced by republics. Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Czechoslovakia became independent countries. Yugoslavia and Romania expanded into former Austro-Hungarian territory. The Soviet Union succeeded the Russian empire in the remainder if its former territory, and Germany, Austria, and Hungary were reduced in size.

In 1938, Nazi Germany annexed Austria and part of Czechoslovakia,

and in 1939, Nazi Germany and the USSR concluded a pact to occupy the

countries that lie between them; the USSR occupied Finland, Estonia,

Latvia, and Lithuania, and Germany and the USSR split Poland in two. The

occupation of Poland started World War II.

Germany attacked the USSR in 1941. The USSR allied with the UK and USA,

and emerged as one of the victors of the war, occupying most of central

and eastern Europe.

After 1945

Planning for decolonization

U.S. and Philippines

In

the United States, the two major parties were divided on the

acquisition of the Philippines, which became a major campaign issue in

1900. The Republicans, who favored permanent acquisition, won the

election, but after a decade or so, Republicans turned their attention

to the Caribbean, focusing on building the Panama Canal. President Woodrow Wilson,

a Democrat in office from 1913 to 1921, ignored the Philippines, and

focused his attention on Mexico and Caribbean nations. By the 1920s, the

peaceful efforts by the Filipino leadership to pursue independence

proved convincing. When the Democrats returned to power in 1933, they

worked with the Filipinos to plan a smooth transition to independence.

It was scheduled for 1946 by Tydings–McDuffie Act

of 1934. In 1935, the Philippines transitioned out of territorial

status, controlled by an appointed governor, to the semi-independent

status of the Commonwealth of the Philippines.

Its constitutional convention wrote a new constitution, which was

approved by Washington and went into effect, with an elected governor Manuel L. Quezon and legislature. Foreign Affairs remained under American control. The Philippines built up a new army, under general Douglas MacArthur,

who took leave from his U.S. Army position to take command of the new

army reporting to Quezon. The Japanese occupation 1942 to 1945 disrupted

but did not delay the transition. It took place on schedule in 1946 as Manuel Roxas took office as president.

Portugal

Portuguese Army special caçadores advancing in the African jungle in the early 1960s, during the Angolan War of Independence.

Although a small, poor country, Portugal had the oldest (it started, in 1415, with the conquer of Ceuta) and one of the largest colonial empires, due to the Portuguese discoveries. Portugal was an authoritarian state (ruled by António de Oliveira Salazar),

with no taste for democracy at home or in its colonies. There was a

fierce determination to maintain possession at all costs, and

aggressively defeat any insurgencies. However, Portugal was helpless

when India seized Goa in 1961. In 1961, nationalist forces began organizing in Portugal, and the revolts (and, then, war - Portuguese Colonial War) spread to Angola, Guinea Bissau and Mozambique.

Lisbon escalated its effort in the war: for instance, it increased the

number of natives in the colonial army and built strategic hamlets.

Portugal sent another 300,000 European settlers into Angola and

Mozambique until 1974. In 1974, left-wing revolution (Carnation Revolution)

inside Portugal destroyed the old system and encouraged pro-Soviet

elements to attempt to seize control in the colonies. The result was a

very long and extremely difficult multi-party Civil War in Angola, and

lesser insurrections in Mozambique.

Belgium

Belgium

is a small, rich European country that had an empire forced upon it by

international demand in 1908 in response to the malfeasance of its King

Leopold in greatly mistreating the Congo. It added Rwanda and Burundi as

League of Nations mandates from the former German Empire in 1919. The

colonies remained independent during the war, while Belgium itself was

occupied by the Germans. There was no serious planning for independence,

and exceedingly little training or education provided. The Belgian Congo

was especially rich, and many Belgian businessmen lobbied hard to

maintain control. Local revolts grew in power and finally, the Belgian

king suddenly announced in 1959 that independence was on the agenda –

and it was hurriedly arranged in 1960, for country bitterly and deeply

divided on social and economic grounds.

The Netherlands

Dutch soldiers in the East Indies during the Indonesian National Revolution, 1946

The Netherlands, a small rich country in Western Europe, had spent

centuries building up its empire. By 1940 it consisted mostly of the Dutch East Indies

(now Indonesia). Its massive oil reserves provided about 14 percent of

the Dutch national product and supported a large population of ethnic

Dutch government officials and businessmen in Jakarta and other major

cities. The Netherlands was overrun and almost starved to death by the

Nazis during the war, and Japan sank the Dutch fleet in seizing the East

Indies. In 1945 the Netherlands could not regain these islands on its

own; it did so by depending on British military help and American

financial grants. By the time Dutch soldiers returned, an independent

government under Sukarno,

originally set up by the Japanese, was in power. The Dutch in the East

Indies, and at home, were practically unanimous (except for the

Communists) that Dutch power and prestige and wealth depended on an

extremely expensive war to regain the islands. Compromises were

negotiated, were trusted by neither side. When the Indonesian Republic

successfully suppressed a large-scale communist revolt, the United

States realized that it needed the nationalist government as an ally in

the Cold War. Dutch possession was an obstacle to American Cold War

goals, so Washington forced the Dutch to grant full independence. A few

years later, Sukarno seized all Dutch properties and expelled all ethnic Dutch—over

300,000—as well as several hundred thousand ethnic Indonesians who

supported the Dutch cause. In the aftermath, the Netherlands prospered

greatly in the 1950s and 1960s but nevertheless public opinion was

bitterly hostile to the United States for betrayal. Washington remained

baffled why the Dutch were so inexplicably enamoured of an obviously

hopeless cause.

United Nations Trust Territories

When the United Nations was formed in 1945, it established trust territories. These territories included the League of Nations mandate territories which had not achieved independence by 1945, along with the former Italian Somaliland. The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

was transferred from Japanese to US administration. By 1990 all but one

of the trust territories had achieved independence, either as

independent states or by merger with another independent state; the Northern Mariana Islands elected to become a commonwealth of the United States.

The emergence of the Third World (1945–present)

Czechoslovak anti-colonialist propaganda poster: "Africa – in fight for freedom".

The term "Third World" was coined by French demographer Alfred Sauvy in 1952, on the model of the Third Estate, which, according to Abbé Sieyès,

represented everything, but was nothing: "...because at the end this

ignored, exploited, scorned Third World like the Third Estate, wants to

become something too" (Sauvy). The emergence of this new political

entity, in the frame of the Cold War,

was complex and painful. Several tentative attempts were made to

organize newly independent states in order to oppose a common front

towards both the US's and the USSR's influence on them, with the

consequences of the Sino-Soviet split already at works. Thus, the Non-Aligned Movement constituted itself, around the main figures of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, Sukarno, the Indonesian president, Josip Broz Tito the Communist leader of Yugoslavia, and Gamal Abdel Nasser, head of Egypt who successfully opposed the French and British imperial powers during the 1956 Suez crisis. After the 1954 Geneva Conference which put an end to the First Indochina War, the 1955 Bandung Conference gathered Nasser, Nehru, Tito, Sukarno, the leader of Indonesia, and Zhou Enlai, Premier of the People's Republic of China. In 1960, the UN General Assembly voted the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. The next year, the Non-Aligned Movement was officially created in Belgrade (1961), and was followed in 1964 by the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which tried to promote a New International Economic Order (NIEO). The NIEO was opposed to the 1944 Bretton Woods system,

which had benefited the leading states which had created it, and

remained in force until 1971 after the United States' suspension of

convertibility from dollars to gold. The main tenets of the NIEO were:

- Developing countries must be entitled to regulate and control the activities of multinational corporations operating within their territory.

- They must be free to nationalise or expropriate foreign property on conditions favourable to them.

- They must be free to set up associations of primary commodities producers similar to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, created on September 17, 1960 to protest pressure by major oil companies (mostly owned by U.S., British, and Dutch nationals) to reduce oil prices and payments to producers); all other states must recognise this right and refrain from taking economic, military, or political measures calculated to restrict it.

- International trade should be based on the need to ensure stable, equitable, and remunerative prices for raw materials, generalised non-reciprocal and non-discriminatory tariff preferences, as well as transfer of technology to developing countries; and should provide economic and technical assistance without any strings attached.

The UN Human Development Index (HDI) is a quantitative index of development, alternative to the classic Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which some use as a proxy to define the Third World. While the GDP only calculates economic wealth, the HDI includes life expectancy, public health and literacy as fundamental factors of a good quality of life. Countries in North America, the Southern Cone, Europe, East Asia, and Oceania generally have better standards of living than countries in Central Africa, East Africa, parts of the Caribbean, and South Asia.

The UNCTAD however wasn't very effective in implementing this New

International Economic Order (NIEO), and social and economic

inequalities between industrialized countries and the Third World kept

on growing throughout the 1960s until the 21st century. The 1973 oil crisis which followed the Yom Kippur War

(October 1973) was triggered by the OPEC which decided an embargo

against the US and Western countries, causing a fourfold increase in the

price of oil, which lasted five months, starting on October 17, 1973,

and ending on March 18, 1974. OPEC nations then agreed, on January 7,

1975, to raise crude oil prices by 10%. At that time, OPEC nations –

including many who had recently nationalized their oil industries –

joined the call for a New International Economic Order to be initiated

by coalitions of primary producers. Concluding the First OPEC Summit in

Algiers they called for stable and just commodity prices, an

international food and agriculture program, technology transfer from

North to South, and the democratization of the economic system. But

industrialized countries quickly began to look for substitutes to OPEC

petroleum, with the oil companies investing the majority of their

research capital in the US and European countries or others, politically

sure countries. The OPEC lost more and more influence on the world

prices of oil.

The second oil crisis occurred in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Then, the 1982 Latin American debt crisis

exploded in Mexico first, then Argentina and Brazil, which proved

unable to pay back their debts, jeopardizing the existence of the

international economic system.

The 1990s were characterized by the prevalence of the Washington consensus on neoliberal policies, "structural adjustment" and "shock therapies" for the former Communist states.

Decolonization of Africa

British decolonisation in Africa

The decolonisation of North Africa, and sub- Saharan Africa took

place in the mid-to-late 1950s, very suddenly, with little preparation.

There was widespread unrest and organised revolts, especially in French

Algeria, Portuguese Angola, the Belgian Congo and British Kenya.

In 1945, Africa had four independent countries – Egypt, Ethiopia, Liberia, and South Africa.

After Italy's defeat in World War II, France and the UK occupied the former Italian colonies. Libya became an independent kingdom in 1951. Eritrea

was merged with Ethiopia in 1952. Italian Somaliland was governed by

the UK, and by Italy after 1954, until its independence in 1960.

By 1977 European colonial rule in mainland Africa had ended. Most

of Africa's island countries had also become independent, although Réunion and Mayotte remain part of France. However the black majorities in Rhodesia and South Africa were disenfranchised until 1979 in Rhodesia, which became Zimbabwe-Rhodesia that year and Zimbabwe the next, and until 1994 in South Africa. Namibia, Africa's last UN Trust Territory, became independent of South Africa in 1990.

Most independent African countries exist within prior colonial borders. However Morocco merged French Morocco with Spanish Morocco, and Somalia formed from the merger of British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland. Eritrea merged with Ethiopia in 1952, but became an independent country in 1993.

Most African countries became independent as republics. Morocco, Lesotho, and Swaziland remain monarchies under dynasties that predate colonial rule. Egypt and Libya gained independence as monarchies, but both countries' monarchs were later deposed, and they became republics.

African countries cooperate in various multi-state associations. The African Union includes all 55 African states. There are several regional associations of states, including the East African Community, Southern African Development Community, and Economic Community of West African States, some of which have overlapping membership.

United Kingdom: Sudan (1956); Ghana (1957); Nigeria (1960); Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (1961); Uganda (1962); Kenya and Sultanate of Zanzibar (1963); Malawi and Zambia (1964); Gambia and Rhodesia (1965); Botswana and Lesotho (1966); Mauritius and Swaziland (1968)

United Kingdom: Sudan (1956); Ghana (1957); Nigeria (1960); Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (1961); Uganda (1962); Kenya and Sultanate of Zanzibar (1963); Malawi and Zambia (1964); Gambia and Rhodesia (1965); Botswana and Lesotho (1966); Mauritius and Swaziland (1968) France: Morocco and Tunisia (1956); Guinea (1958); Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Senegal, Madagascar, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Gabon and Mauritania (1960); Algeria (1962); Comoros (1975); Djibouti (1977)

France: Morocco and Tunisia (1956); Guinea (1958); Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Senegal, Madagascar, Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Gabon and Mauritania (1960); Algeria (1962); Comoros (1975); Djibouti (1977) Spain: Equatorial Guinea (1968)

Spain: Equatorial Guinea (1968) Portugal: Guinea-Bissau (1974); Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe and Angola (1975)

Portugal: Guinea-Bissau (1974); Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe and Angola (1975) Belgium: Democratic Republic of the Congo (1960); Burundi and Rwanda (1962)

Belgium: Democratic Republic of the Congo (1960); Burundi and Rwanda (1962)

Decolonization in the Americas after 1945

United Kingdom: Newfoundland (formerly an independent dominion but under direct British rule since 1934) (1949, union with Canada); Jamaica (1962); Trinidad and Tobago (1962); Barbados (1962); Guyana (1966); Bahamas (1973): Grenada (1974); Dominica (1978); Saint Lucia (1979); St. Vincent and the Grenadines (1979); Antigua and Barbuda (1981); Belize (1981); Saint Kitts and Nevis (1983).

United Kingdom: Newfoundland (formerly an independent dominion but under direct British rule since 1934) (1949, union with Canada); Jamaica (1962); Trinidad and Tobago (1962); Barbados (1962); Guyana (1966); Bahamas (1973): Grenada (1974); Dominica (1978); Saint Lucia (1979); St. Vincent and the Grenadines (1979); Antigua and Barbuda (1981); Belize (1981); Saint Kitts and Nevis (1983). Netherlands: Netherlands Antilles, Suriname (1954, both becoming constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands), 1975 (independence of Suriname)

Netherlands: Netherlands Antilles, Suriname (1954, both becoming constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands), 1975 (independence of Suriname) Denmark: Greenland (1979, became a constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark).

Denmark: Greenland (1979, became a constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark).

Decolonization of Asia

Western European colonial empires in Asia and Africa all collapsed in the years after 1945

Four nations (India, Pakistan, Dominion of Ceylon, and Union of Burma) that gained independence in 1947 and 1948

Japan expanded its occupation of Chinese territory during the 1930s, and occupied Southeast Asia during World War II. After the war, the Japanese colonial empire

was dissolved, and national independence movements resisted the

re-imposition of colonial control by European countries and the United

States.

The Republic of China

regained control of Japanese-occupied territories in Manchuria and

eastern China, as well as Taiwan. Only Hong Kong and Macau remained in

outside control.

The Allied powers divided Korea into two occupation zones, which became the states of North Korea and South Korea. The Philippines became independent of the US in 1946.

The Netherlands recognized Indonesia's independence in 1949, after a four-year independence struggle. Indonesia annexed Netherlands New Guinea in 1963, and Portuguese Timor in 1975. In 2002, former Portuguese Timor became independent as East Timor.

The following list shows the colonial powers following the end of

hostilities in 1945, and their colonial or administrative possessions.

The year of decolonization is given chronologically in parentheses.

United Kingdom: Transjordan (1946), British India and Pakistan (1947); British Mandate of Palestine, Burma, Ceylon (1948); British Malaya (1957); Kuwait (1961); Kingdom of Sarawak, North Borneo and Singapore (1963); Maldives (1965); United Arab Emirates (1971); Brunei (1984); Hong Kong (1997)

United Kingdom: Transjordan (1946), British India and Pakistan (1947); British Mandate of Palestine, Burma, Ceylon (1948); British Malaya (1957); Kuwait (1961); Kingdom of Sarawak, North Borneo and Singapore (1963); Maldives (1965); United Arab Emirates (1971); Brunei (1984); Hong Kong (1997) France: French India (1954) and Indochina comprising Vietnam (1945), Cambodia (1953) and Laos (1953)

France: French India (1954) and Indochina comprising Vietnam (1945), Cambodia (1953) and Laos (1953) Portugal: Portuguese India (1961); East Timor (1975); Macau (1999)

Portugal: Portuguese India (1961); East Timor (1975); Macau (1999) United States: Philippines (1946)

United States: Philippines (1946) Netherlands: Indonesia (1949)

Netherlands: Indonesia (1949)

Decolonization in Europe

Italy had occupied the Dodecanese

islands in 1912, but Italian occupation ended after World War II, and

the islands were integrated into Greece. British rule ended in Cyprus in 1960, and Malta in 1964, and both islands became independent republics.

Soviet control of its non-Russian member republics weakened

rapidly as movements for democratization and self-government gained

strength during 1990 and 1991. The Soviet coup d'état attempt in August 1991 began the breakup of the USSR, which formally ended on December 26, 1991. The Republics of the Soviet Union become sovereign states—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Byelorussia (later Belarus), Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Historian Robert Daniels says, "A special dimension that the

anti-Communist revolutions shared with some of their predecessors was

decolonization."

Moscow's policy had long been to settle ethnic Russians in the

non-Russian republics. After independence, minority rights for

Russian-speakers has been an issue; see Russians in the Baltic states.

Decolonization of Oceania

The

decolonization of Oceania occurred after World War II when nations in

Oceania achieved independence by transitioning from European colonial

rule to full independence.

United Kingdom: Tonga and Fiji (1970); Solomon Islands and Tuvalu (1978); Kiribati (1979)

United Kingdom: Tonga and Fiji (1970); Solomon Islands and Tuvalu (1978); Kiribati (1979) United Kingdom and

United Kingdom and  France: Vanuatu (1980)

France: Vanuatu (1980) Australia: Nauru (1968); Papua New Guinea (1975)

Australia: Nauru (1968); Papua New Guinea (1975) New Zealand: Samoa (1962)

New Zealand: Samoa (1962) United States: Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia (1986); Palau (1994)

United States: Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia (1986); Palau (1994)

Challenges

Typical challenges of decolonization include state-building, nation-building, and economic development.

State-building

After independence, the new states needed to establish or strengthen

the institutions of a sovereign state – governments, laws, a military,

schools, administrative systems, and so on. The amount of self-rule

granted prior to independence, and assistance from the colonial power

and/or international organisations after independence, varied greatly

between colonial powers, and between individual colonies.

Except for a few absolute monarchies, most post-colonial states are either republics or constitutional monarchies. These new states had to devise constitutions, electoral systems, and other institutions of representative democracy.

Nation-building

The Black Star Monument in Accra, built by Ghana's first president Kwame Nkrumah to commemorate the country's independence

Nation-building is the process of creating a sense of identification

with, and loyalty to, the state. Nation-building projects seek to

replace loyalty to the old colonial power, and/or tribal or regional

loyalties, with loyalty to the new state. Elements of nation-building

include creating and promoting symbols of the state like a flag and an

anthem, monuments, official histories, national sports teams, codifying

one or more indigenous official languages, and replacing colonial place-names with local ones. Nation-building after independence often continues the work began by independence movements during the colonial period.

Settled populations

Decolonization

is not an easy matter in colonies where a large population of settlers

lives, particularly if they have been there for several generations.

This population, in general, was often repatriated, often losing considerable property. For instance, the decolonization of Algeria by France was particularly uneasy due to the large European population, which largely evacuated to France when Algeria became independent. In Zimbabwe, former Rhodesia, president Robert Mugabe has, starting in the 1990s, targeted white African farmers

and forcibly seized their property. Other ethnic minorities that are

also the product of colonialism may pose problems as well. A large

Indian community lived in Uganda

– as in most of East Africa – as a result of Britain colonizing both

India and East Africa. As many Indians had considerable wealth Idi Amin expelled them for domestic political gain.

Economic development

Newly independent states also had to develop independent economic

institutions – a national currency, banks, companies, regulation, tax

systems, etc.

Many colonies were serving as resource colonies which produced

raw materials and agricultural products, and as a captive market for

goods manufactured in the colonizing country. Many decolonized countries

created programs to promote industrialization. Some nationalized industries and infrastructure, and some engaged in land reform to redistribute land to individual farmers or create collective farms.

Some decolonized countries maintain strong economic ties with the former colonial power. The CFA franc

is a currency shared by 14 countries in West and Central Africa, mostly

former French colonies. The CFA franc is guaranteed by the French

treasury.

After independence, many countries created regional economic

associations to promote trade and economic development among

neighbouring countries, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Effects on the colonizers

John Kenneth Galbraith argues that the post–World War II decolonization was brought about for economic reasons. In A Journey Through Economic Time, he writes:

"The engine of economic well-being was now within and between the advanced industrial countries. Domestic economic growth – as now measured and much discussed – came to be seen as far more important than the erstwhile colonial trade.... The economic effect in the United States from the granting of independence to the Philippines was unnoticeable, partly due to the Bell Trade Act, which allowed American monopoly in the economy of the Philippines. The departure of India and Pakistan made small economic difference in the United Kingdom. Dutch economists calculated that the economic effect from the loss of the great Dutch empire in Indonesia was compensated for by a couple of years or so of domestic post-war economic growth. The end of the colonial era is celebrated in the history books as a triumph of national aspiration in the former colonies and of benign good sense on the part of the colonial powers. Lurking beneath, as so often happens, was a strong current of economic interest – or in this case, disinterest."

In general, the release of the colonized caused little economic loss

to the colonizers. Part of the reason for this was that major costs were

eliminated while major benefits were obtained by alternate means.

Decolonization allowed the colonizer to disclaim responsibility for the

colonized. The colonizer no longer had the burden of obligation,

financial or otherwise, to their colony. However, the colonizer

continued to be able to obtain cheap goods and labor as well as economic

benefits (see Suez Canal Crisis)

from the former colonies. Financial, political and military pressure

could still be used to achieve goals desired by the colonizer. Thus

decolonization allowed the goals of colonization to be largely achieved,

but without its burdens.

Cultural

Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o has written about colonization and decolonization in the film universe. Born in Ethiopia, filmmaker Haile Gerima describes the "colonization of the unconscious" he describes experiencing as a child:

...as kids, we tried to act out the things we had seen in the movies. We used to play cowbows and Indians in the mountains around Gondar...We acted out the roles of these heroes, identifying with the cowboys conquering the Indians. We didn't identify with the Indians at all and we never wanted the Indians to win. Even in Tarzan movies, we would become totally galvanized by the activities of the hero and follow the story from his point of view, completely caught up in the structure of the story. Whenever Africans sneaked up behind Tarzan, we would scream our heads off, trying to warn him that 'they' were coming".

In Asia, kung fu cinema

emerged at a time Japan wanted to reach Asian populations in other

countries by way of its cultural influence. The surge in popularity of

kung fu movies began in the late 1960s through the 1970s. Local

populations were depicted as protagonists opposing "imperialists"

(foreigners) and their "Chinese collaborators".

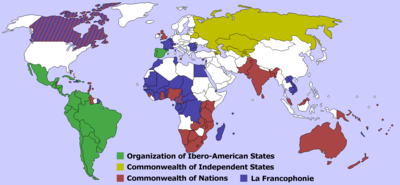

Post-colonial organizations

Four international organizations whose membership largely follows the pattern of previous colonial empires.

Due to a common history and culture, former colonial powers created

institutions which more loosely associated their former colonies.

Membership is voluntary, and in some cases can be revoked if a member

state loses some objective criteria (usually a requirement for

democratic governance). The organizations serve cultural, economic, and

political purposes between the associated countries, although no such

organisation has become politically prominent as an entity in its own

right.

| Former Colonial Power | Organisation | Founded |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Commonwealth of Nations | 1931 |

| France | French Union | 1946 |

| French Community | 1958 | |

| La Francophonie | 1970 | |

| Spain & Portugal | Latin Union | 1954 |

| Organisation of Ibero-American States | 1991 | |

| Portugal | Community of Portuguese Language Countries | 1996 |

| Russia | Commonwealth of Independent States | 1991 |

| United States | Commonwealths | 1934 |

| Freely Associated States | 1982 | |

| Netherlands | De Nederlandse Unie | 1949 |

| De Nederlandse Taalunie | 1980 |

Assassinated anti-colonialist leaders

Gandhi in 1947, with Lord Louis Mountbatten, Britain's last Viceroy of India, and his wife Vicereine Edwina Mountbatten.

A non-exhaustive list of assassinated leaders would include:

- Tiradentes was a leading member of the Brazilian seditious movement known as the Inconfidência Mineira, against the Portuguese Empire. He fought for an independent Brazilian republic.

- Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, nonviolent leader of the Indian independence movement was assassinated in 1948 by Nathuram Godse.

- Ruben Um Nyobé, leader of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), killed by the French SDECE on September 13, 1958. No clear cause has ever been ascertained for the mysterious crash. Assassination has been alleged.

- Barthélemy Boganda, leader of a nationalist Central African Republic movement, who died in a plane-crash on March 29, 1959, eight days before the last elections of the colonial era.

- Félix-Roland Moumié, successor to Ruben Um Nyobe at the head of the Cameroon's People Union, assassinated in Geneva in 1960 by the SDECE (French secret services).[55]

- Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was assassinated on January 17, 1961.

- Burundi nationalist Louis Rwagasore was assassinated on October 13, 1961, while Pierre Ngendandumwe, Burundi's first Hutu prime minister, was also murdered on January 15, 1965.

- Sylvanus Olympio, the first president of Togo, was assassinated on January 13, 1963.

- Mehdi Ben Barka, the leader of the Moroccan National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF) and of the Tricontinental Conference, which was supposed to prepare in 1966 in Havana its first meeting gathering national liberation movements from all continents – related to the Non-Aligned Movement, but the Tricontinal Conference gathered liberation movements while the Non-Aligned were for the most part states – was "disappeared" in Paris in 1965, allegedly by Moroccan agents and French police officers.

- Nigerian leader Ahmadu Bello was assassinated in January 1966 during a coup which toppled Nigeria's post-independence government.

- Eduardo Mondlane, the leader of FRELIMO and the father of Mozambican independence, was assassinated in 1969. Both the Portuguese intelligence or the Portuguese secret police PIDE/DGS and elements of FRELIMO, have been accused of killing Mondlane.

- Mohamed Bassiri, Sahrawi leader of the Movement for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Wadi el Dhahab was "disappeared" in El Aaiún in 1970, allegedly by the Spanish Legion.

- Amílcar Cabral was killed on January 20, 1973 by PAIGC rival Inocêncio Kani, with the help of Portuguese agents operating within the PAIGC.