Millennials, also known as Generation Y (or simply Gen Y), are the demographic cohort following Generation X and preceding Generation Z. Researchers and popular media use the early 1980s as starting birth years and the mid-1990s to early 2000s as ending birth years, with 1981 to 1996 a widely accepted defining range for the generation.

Millennials are sometimes referred to as "echo boomers" due to a major surge in birth rates in the 1980s and 1990s, and because millennials are often the children of the baby boomers. This generation is generally marked by their coming of age in the Information Age, and they are comfortable in their usage of digital technology and social media. Millennials are often the parents of Generation Alpha.

Terminology

Members of this demographic cohort are known as millennials because they became adults around the turn of the millennium.Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe are widely credited with naming the millennials. They coined the term in 1987, around the time children born in 1982 were entering kindergarten, and the media were first identifying their prospective link to the impending new millennium as the high school graduating class of 2000. They wrote about the cohort in their books Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069 (1991) and Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000).

In August 1993, an Advertising Age editorial coined the phrase Generation Y to describe teenagers of the day, then aged 13–19 (born 1974–1980), who were at the time defined as different from Generation X. However, the 1974–1980 cohort was later reidentified as the last wave of Generation X, and by 2003 Ad Age had moved their Generation Y starting year up to 1982. According to journalist Bruce Horovitz, in 2012, Ad Age "threw in the towel by conceding that millennials is a better name than Gen Y", and by 2014, a past director of data strategy at Ad Age said to NPR "the Generation Y label was a placeholder until we found out more about them".

Millennials are sometimes called Echo Boomers, due to their being the offspring of the baby boomers and due to the significant increase in birth rates from the early 1980s to mid 1990s, mirroring that of their parents. In the United States, birth rates peaked in August 1990 and a 20th-century trend toward smaller families in developed countries continued. Psychologist Jean Twenge described millennials as "Generation Me" in her 2006 book Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – and More Miserable Than Ever Before, which was updated in 2014. In 2013, Time magazine ran a cover story titled Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation. Newsweek used the term Generation 9/11 to refer to young people who were between the ages of 10 and 20 during the terrorist acts of September 11, 2001. The first reference to "Generation 9/11" was made in the cover story of the 12 November 2001 issue of Newsweek. Alternative names for this group proposed include the Net Generation and The Burnout Generation.

American sociologist Kathleen Shaputis labeled millennials as the Boomerang Generation or Peter Pan generation because of the members' perceived tendency for delaying some rites of passage into adulthood for longer periods than most generations before them. These labels were also a reference to a trend toward members living with their parents for longer periods than previous generations. Kimberly Palmer regards the high cost of housing and higher education, and the relative affluence of older generations, as among the factors driving the trend. Questions regarding a clear definition of what it means to be an adult also impact a debate about delayed transitions into adulthood and the emergence of a new life stage, Emerging Adulthood. A 2012 study by professors at Brigham Young University found that college students were more likely to define "adult" based on certain personal abilities and characteristics rather than more traditional "rite of passage" events. Larry Nelson noted that "In prior generations, you get married and you start a career and you do that immediately. What young people today are seeing is that approach has led to divorces, to people unhappy with their careers … The majority want to get married […] they just want to do it right the first time, the same thing with their careers."

Date and age range definitions

Oxford Living Dictionaries describes a millennial as "a person reaching young adulthood in the early 21st century." Jonathan Rauch, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote for The Economist in 2018 that "generations are squishy concepts", but the 1981 to 1996 birth cohort is a "widely accepted" definition for millennials. Reuters also states that millennials are "widely accepted as having been born between 1981 and 1996."The Pew Research Center defines millennials as born from 1981 to 1996, choosing these dates for "key political, economic and social factors", including the September 11th terrorist attacks, the Great Recession, and the Internet explosion. According to this definition, as of 2020 the oldest millennial is 39 years old, and the youngest will turn 24 this year. Many major media outlets and statistical organizations have cited Pew's definition including Time magazine, BBC, The Washington Post, Business Insider, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Pew has observed that "Because generations are analytical constructs, it takes time for popular and expert consensus to develop as to the precise boundaries that demarcate one generation from another" and has indicated that they would remain open to date recalibration.

The Federal Reserve Board defines millennials as "members of the generation born between 1981 and 1996", as does the American Psychological Association and Ernst and Young. The birth years of 1981 to 1996 have also been used to define millennials by PBS, CBS, ABC Australia, The Washington Post, The Washington Times, The Los Angeles Times.

Gallup Inc., MSW Research, and the Resolution Foundation use 1980–1996, while PricewaterhouseCoopers has used 1981 to 1995, and Nielsen Media Research has defined millennials as adults between the ages of 22 and 38 years old in 2019. In 2014, U.S PIRG described millennials as those born between 1983 and 2000. CNN reports that studies use 1981–1996 but sometimes 1980–2000. The United States Census Bureau used the birth years 1982 to 2000 in a 2015 news release to describe millennials, but they have stated that "there is no official start and end date for when millennials were born" and they do not define millennials.

Australia's McCrindle Research uses 1980–1994 as Generation Y birth years.

For the polling agency Ipsos-MORI, the term 'millennial' is a "working title" for the cohort born between 1980 and 1995. They further noted that while this cohort has its own unique characteristics, it is plagued by misunderstandings or plainly wrong descriptions.

In his 2008 book The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom, author Elwood Carlson used the term "New Boomers" to describe this cohort. He identified the birth years of 1983–2001, based on the upswing in births after 1983 and finishing with the "political and social challenges" that occurred after the September 11th terrorist acts. Author Neil Howe, co-creator of the Strauss–Howe generational theory, defines millennials as being born between 1982–2004; however, Howe described the dividing line between millennials and the following generation, which he termed the Homeland Generation, as "tentative", saying "you can’t be sure where history will someday draw a cohort dividing line until a generation fully comes of age".

Individuals born in the Generation X and millennial cusp years of the late 1970s and early to mid 1980s have been identified as a "microgeneration" with characteristics of both generations. Names given to these "cuspers" include Xennials, Generation Catalano, and the Oregon Trail Generation.

General discussion

Psychologist Jean Twenge, the author of the 2006 book Generation Me, considers millennials, along with younger members of Generation X, to be part of what she calls "Generation Me". Twenge attributes millennials with the traits of confidence and tolerance, but also describes a sense of entitlement and narcissism, based on "Narcissistic Personality Inventory" surveys showing increased narcissism among millennials compared to preceding generations when they were teens and in their twenties. Psychologist Jeffrey Arnett of Clark University, Worcester has criticized Twenge's research on narcissism among millennials, stating "I think she is vastly misinterpreting or over-interpreting the data, and I think it’s destructive". He doubts that the Narcissistic Personality Inventory really measures narcissism at all. Arnett says that not only are millennials less narcissistic, they're “an exceptionally generous generation that holds great promise for improving the world”. A study published in 2017 in the journal Psychological Science found a small decline in narcissism among young people since the 1990s.Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe argue that each generation has common characteristics that give it a specific character with four basic generational archetypes, repeating in a cycle. According to their hypothesis, they predicted millennials would become more like the "civic-minded" G.I. Generation with a strong sense of community both local and global. Strauss and Howe ascribe seven basic traits to the millennial cohort: special, sheltered, confident, team-oriented, conventional, pressured, and achieving. However, Arthur E. Levine, author of When Hope and Fear Collide: A Portrait of Today's College Student, dismissed these generational images as "stereotypes". In addition, psychologist Jean Twenge says Strauss and Howe's assertions are overly-deterministic, non-falsifiable, and unsupported by rigorous evidence.

Polling agency Ipsos-MORI warned that the word 'millennials' is "misused to the point where it’s often mistaken for just another meaningless buzzword" because "many of the claims made about millennial characteristics are simplified, misinterpreted or just plain wrong, which can mean real differences get lost" and that "[e]qually important are the similarities between other generations – the attitudes and behaviours that are staying the same are sometimes just as important and surprising."

Cultural identity

Of millennials in the United States

Since the 2000 U.S. Census, millennials have taken advantage of the possibility of selecting more than one racial group in abundance. In 2015, the Pew Research Center also conducted research regarding generational identity that said a majority did not like the "Millennial" label. In 2015, the Pew Research Center conducted research regarding generational identity. It was discovered that millennials are less likely to strongly identify with the generational term when compared to Generation X or the Baby Boomers, with only 40% of those born between 1981 and 1997 identifying as part of the Millennial Generation. Among older millennials, those born 1981–1988, Pew Research found 43% personally identified as members of the older demographic cohort, Generation X, while only 35% identified as millennials. Among younger millennials (born 1989–1997), generational identity was not much stronger, with only 45% personally identifying as millennials. It was also found that millennials chose most often to define themselves with more negative terms such as self-absorbed, wasteful or greedy. In this 2015 report, Pew defined millennials with birth years ranging from 1981 onwards.Fred Bonner, a Samuel DeWitt Proctor Chair in Education at Rutgers University and author of Diverse Millennial Students in College: Implications for Faculty and Student Affairs, believes that much of the commentary on the Millennial Generation may be partially correct, but overly general and that many of the traits they describe apply primarily to "white, affluent teenagers who accomplish great things as they grow up in the suburbs, who confront anxiety when applying to super-selective colleges, and who multitask with ease as their helicopter parents hover reassuringly above them." During class discussions, Bonner listened to black and Hispanic students describe how some or all of the so-called core traits did not apply to them. They often said that the "special" trait, in particular, is unrecognizable. Other socioeconomic groups often do not display the same attributes commonly attributed to millennials. "It's not that many diverse parents don't want to treat their kids as special," he says, "but they often don't have the social and cultural capital, the time and resources, to do that."

American Millennials that have, or are, serving in the military may have drastically different views and opinions than their non-veteran counterparts. Because of this, some do not identify with their generation; this coincides with most millennials having a lack of exposure and knowledge of the military, yet trust its leadership. Yet, the view of some senior leadership of serving millennials are not always positive.

A vinyl record up close

The University of Michigan's

"Monitoring the Future" study of high school seniors (conducted

continually since 1975) and the American Freshman Survey, conducted by

UCLA's Higher Education Research Institute of new college students since

1966, showed an increase in the proportion of students who consider

wealth a very important attribute, from 45% for Baby Boomers (surveyed

between 1967 and 1985) to 70% for Gen Xers, and 75% for millennials. The

percentage who said it was important to keep abreast of political

affairs fell, from 50% for Baby Boomers to 39% for Gen Xers, and 35% for

millennials. The notion of "developing a meaningful philosophy of life"

decreased the most across generations, from 73% for Boomers to 45% for

millennials. The willingness to be involved in an environmental cleanup

program dropped from 33% for Baby Boomers to 21% for millennials.

By the late 2010s, viewership of late-night American television

among adults aged 18 to 49, the most important demographic group for

advertisers, has fallen substantially despite an abundance of materials.

This is due in part to the availability and popularity of streaming

services. However, when delayed viewing within three days is taken into

account, the top shows all saw their viewership numbers boosted. This

development undermines the current business model of the television

entertainment industry. "If the sky isn't exactly falling on the

broadcast TV advertising model, it certainly seems to be a lot closer to

the ground than it once was," wrote reporter Anthony Crupi for Ad Age.

Despite having the reputation for "killing" many things of value

to the older generations, Millennials and Generation Z are nostalgically

preserving Polaroid cameras, vinyl records, needlepoint, and home gardening, to name just some.

Of millennials in general and in other countries

Glastonbury Festival in England.

Elza Venter, an educational psychologist and lecturer at Unisa, South

Africa, in the Department of Psychology of Education, believes

Millennials are digital natives because they have grown up experiencing

digital technology and have known it all their lives. Prensky coined the

concept ‘digital natives’ because the members of the generation are

‘native speakers of the digital language of computers, video games and

the internet’. This generation's older members use a combination of face-to-face communication and computer mediated communication, while its younger members use mainly electronic and digital technologies for interpersonal communication.

A 2013 survey of almost a thousand Britons aged 18 to 24 found

that 62% had a favorable opinion of the British Broadcasting Corporation

(BBC) and 70% felt proud of their national history. In 2017, nearly half of millennials living in the UK have attended a live music event.

Only 54% of Russian millennials were married in 2016.

Millennials came of age in a time where the entertainment industry began to be affected by the Internet. Using artificial intelligence, Joan Serra and his team at the Spanish National Research Council

studied the massive Million Song Dataset and found that between 1955

and 2010, popular music has gotten louder, while the chords, melodies,

and types of sounds used have become increasingly homogenized. While the

music industry has long been accused of producing songs that are louder

and blander, this is the first time the quality of songs is

comprehensively studied and measured.

Demographics

Asia

Chinese millennials are commonly called the post-80s and post-90s generations. At a 2015 conference in Shanghai organized by University of Southern California's

US-China Institute, millennials in China were examined and contrasted

with American millennials. Findings included millennials' marriage,

childbearing, and child raising preferences, life and career ambitions,

and attitudes towards volunteerism and activism.

As a result of cultural ideals, government policy, and modern

medicine, there has been severe gender imbalances in China and India.

According to the United Nations, in 2018, there were 112 Chinese males

aged 15 to 29 for every hundred females in that age group. That number

in India was 111. China had a total of 34 million excess males and India

37 million, more than the entire population of Malaysia. Such a

discrepancy fuels loneliness epidemics, human trafficking (from

elsewhere in Asia, such as Cambodia and Vietnam), and prostitution,

among other societal problems.

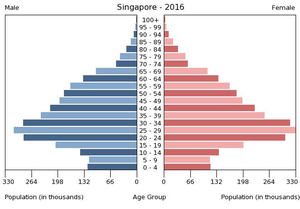

Singapore's birth rate has fallen below the replacement level of

2.1 since the 1980s before stabilizing by during the 2000s and 2010s. (It reached 1.14 in 2018, making it the lowest since 2010 and one of the lowest in the world.)

Government incentives such as the baby bonus have proven insufficient

to raise the birth rate. Singapore's experience mirrors those of Japan

and South Korea.

Vietnam's median age in 2018 was 26 and rising. Between the 1970s and the late 2010s, life expectancy climbed from 60 to 76.

It is now the second highest in Southeast Asia. Vietnam's fertility

rate dropped from 5 in 1980 to 3.55 in 1990 and then to 1.95 in 2017. In

that same year, 23% of the Vietnamese population was 15 years of age or

younger, down from almost 40% in 1989. Other rapidly growing Southeast Asian countries, such as the Philippines, saw similar demographic trends.

Europe

Population pyramid of the European Union in 2016

From about 1750 to 1950, Western Europe

transitioned from having both high birth and death rates to low birth

and death rates. By the late 1960s or 1970s, the average woman had fewer

than two children, and, although demographers at first expected a

"correction," such a rebound never came. Despite a bump in the total

fertility rates (TFR) of some European countries in the very late

twentieth century (the 1980s and 1990s), especially France and Scandinavia,

they never returned to replacement level; the bump was largely due to

older women realizing their dreams of motherhood. At first, falling

fertility is due to urbanization and decreased infant mortality

rates, which diminished the benefits and increased the costs of raising

children. In other words, it became more economically sensible to

invest more in fewer children, as economist Gary Becker

argued. (This is the first demographic transition.) Falling fertility

then came from attitudinal shifts. By the 1960s, people began moving

from traditional and communal values towards more expressive and

individualistic outlooks due to access to and aspiration of higher

education, and to the spread of lifestyle values once practiced only by a

tiny minority of cultural elites. (This is the second demographic transition.)

Although the momentous cultural changes of the 1960s leveled off by the

1990s, the social and cultural environment of the very late

twentieth-century was quite different from that of the 1950s. Such

changes in values have had a major effect on fertility. Member states of

the European Economic Community

saw a steady increase in not just divorce and out-of-wedlock births

between 1960 and 1985 but also falling fertility rates. In 1981, a

survey of countries across the industrialized world

found that while more than half of people aged 65 and over thought that

women needed children to be fulfilled, only 35% of those between the

ages of 15 to 24 (younger Baby Boomers and older Generation X) agreed. In the early 1980s, East Germany, West Germany, Denmark, and the Channel Islands had some of the world's lowest fertility rates.

At the start of the twenty-first century, Europe suffers from an aging population. This problem is especially acute in Eastern Europe,

whereas in Western Europe, it is alleviated by international

immigration. In addition, an increasing number of children born in

Europe has been born to non-European parents. Because children of

immigrants in Europe tend to be about as religious as they are, this

could slow the decline of religion (or the growth of secularism) in the continent as the twenty-first century progresses.

In the United Kingdom, the number of foreign-born residents stood at 6%

of the population in 1991. Immigration subsequently surged and has not

fallen since (as of 2018). Researches by the demographers and political

scientists Eric Kaufmann, Roger Eatwell, and Matthew Goodwin suggest that such a fast ethno-demographic change is one of the key reasons behind public backlash in the form of national populism across the rich liberal democracies, an example of which is the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum (Brexit).

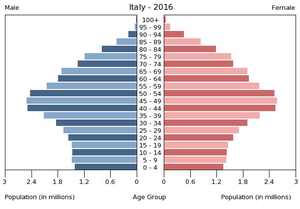

Italy is a country where the problem of an aging population is

especially acute. The fertility rate dropped from about four in the

1960s down to 1.2 in the 2010s. This is not because young Italians do

not want to procreate. Quite the contrary, having many children is an

Italian ideal. But its economy has been floundering since the Great Recession of 2007–8, with the youth unemployment

rate at a staggering 35% in 2019. Many Italians have moved abroad –

150,000 did in 2018 – and many are young people pursuing educational and

economic opportunities. With the plunge in the number of births each

year, the Italian population is expected to decline in the next five

years. Moreover, the Baby Boomers are retiring in large numbers, and

their numbers eclipse those of the young people taking care of them.

Only Japan has an age structure more tilted towards the elderly.

Greece also suffers from a serious demographic problem as many

young people are leaving the country in search of better opportunities

elsewhere in the wake of the Great Recession. This brain drain and a rapidly aging population could spell disaster for the country.

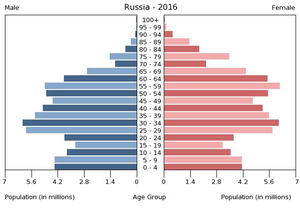

As a result of the shocks due to the decline and dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia's birth rates began falling in the late 1980s while death rates have risen, especially among men.

In the early 2000s, Russia had not only a falling birth rate but also a

declining population despite having an improving economy.

Between 1992 and 2002, Russia's population dropped from 149 million to

144 million. According to the "medium case scenario" of the U.N.'s

Population Division, Russia could lose another 20 million people by the

2020s.

Oceania

Australia's total fertility rate has fallen from above three in the

post-war era, to about replacement level (2.1) in the 1970s to below

that in the late 2010s. However, immigration has been offsetting the

effects of a declining birthrate. In the 2010s, among the residents of

Australia, 5% were born in the United Kingdom, 2.5% from China, 2.2%

from India, and 1.1% from the Philippines. 84% of new arrivals in the

fiscal year of 2016 were below 40 years of age, compared to 54% of those

already in the country. Like other immigrant-friendly countries, such

as Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Australia's

working-age population is expected to grow till about 2025. However, the

ratio of people of working age to retirees (the dependency ratio)

has gone from eight in the 1970s to about four in the 2010s. It could

drop to two by the 2060s, depending in immigration levels.

"The older the population is, the more people are on welfare benefits,

we need more health care, and there's a smaller base to pay the taxes,"

Ian Harper of the Melbourne Business School told ABC News (Australia).

While the government has scaled back plans to increase the retirement

age, to cut pensions, and to raise taxes due to public opposition,

demographic pressures continue to mount as the buffering effects of

immigration are fading away.

United States

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

(also known as the Hart-Cellar Act), passed at the urging of President

Lyndon B. Johnson, abolished national quotas for immigrants and replaced

it with a system that admits a fixed number of persons per year based

in qualities such as skills and the need for refuge. Immigration

subsequently surged from elsewhere in North America (especially Canada

and Mexico), Asia, Central America, and the West Indies.

By the mid-1980s, most immigrants originated from Asia and Latin

America. Some were refugees from Vietnam, Cuba, Haiti, and other parts

of the Americas while others came illegally by crossing the long and

largely undefended U.S.-Mexican border. Although Congress offered

amnesty to "undocumented immigrants" who had been in the country for a

long time and attempted to penalize employers who recruited them, their

influx continued. At the same time, the postwar baby boom and

subsequently falling fertility rate seemed to jeopardize America's

social security system as the Baby Boomers retire in the twenty-first

century.

Provisional data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention

reveal that U.S. fertility rates have fallen below the replacement level

of 2.1 since 1971. (In 2017, it fell to 1.765.)

Among women born during the late 1950s, one fifth had no children,

compared to 10% of those born in the 1930s, thereby leaving behind

neither genetic nor cultural legacy. 17.4% of women from the Baby Boomer

generation had only one child each and were responsible for only 7.8%

of the next generation. On the other hand, 11% of Baby Boomer women gave

birth to at least four children each, for a grand total of one quarter

of the Millennial generation. This will likely cause cultural,

political, and social changes in the future as parents wield a great

deal of influence on their children. For example, by the early 2000s, it

had already become apparent that mainstream American culture was

shifting from secular individualism towards religiosity.

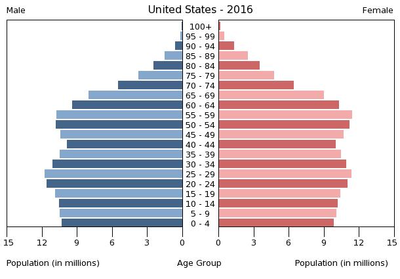

Population pyramid of the United States in 2016

Millennial population size varies, depending on the definition used.

In 2014, using dates ranging from 1982 to 2004, Neil Howe revised the

number to over 95 million people in the U.S. In a 2012 Time magazine article, it was estimated that there were approximately 80 million U.S. millennials. The United States Census Bureau, using birth dates ranging from 1982 to 2000, stated the estimated number of U.S. millennials in 2015 was 83.1 million people.

In 2017, fewer than 56% Millennial were non-Hispanic whites, compared with more than 84% of Americans in their 70s and 80s, 57% had never been married, and 67% lived in a metropolitan area. According to the Brookings Institution,

millennials are the “demographic bridge between the largely white older

generations (pre-millennials) and much more racially diverse younger

generations (post-millennials).”

By analyzing data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Pew Research

Center estimated that millennials, whom they define as people born

between 1981 and 1996, outnumbered baby boomers, born from 1946 to 1964,

for the first time in 2019. That year, there were 72.1 million

millennials compared to 71.6 million baby boomers, who had previously

been the largest living adult generation in the country. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics

shows that about 62 million millennials were born in the United States,

compared to 55 million members of Generation X, 76 million baby

boomers, and 47 million from the Silent Generation. Between 1981 and

1996, an average of 3.6 babies (millennials) were born each year,

compared to 3.4 million (Generation X) between 1965 and 1980. But

millennials continue to grow in numbers as a result of immigration and

naturalization. In fact, millennials form the largest group of

immigrants to the United States in the 2010s. Pew projected that the

millennial generation would reach around 74.9 million in 2033, after

which mortality would outweigh immigration.

Yet 2020 would be the first time millennials (who are between the ages

of 24 and 39) find their share of the electorate shrink as the leading

wave of Generation Z (aged 18 to 23) became eligible to vote. In other

words, their electoral power peaked in 2016. In absolute terms, however,

the number of foreign-born millennials continues to increase as they

become naturalized citizens. In fact, 10% of American voters were born

outside the country by the 2020 election, up from 6% in 2000. The fact

that people from different racial or age groups vote differently means

that this demographic change will influence the future of the American

political landscape. While younger voters hold significantly different

views from their elders, they are considerably less likely to vote.

Non-whites tend to favor candidates from the Democratic Party while

whites by and large prefer the Republican Party.

According to the Pew Research Center, "Among men, only 4% of millennials [ages 21 to 36 in 2017] are veterans, compared with 47%" of men in their 70s and 80s, "many of whom came of age during the Korean War and its aftermath." Some of these former military service members are combat veterans, having fought in Afghanistan and/or Iraq. As of 2016, millennials are the majority of the total veteran population.

According to the Pentagon in 2016, 19% of Millennials are interested in

serving in the military, and 15% have a parent with a history of

military service.

Economic prospects and trends

According to the International Labor Organization (ILO),

200 million people were unemployed in 2015. Of these, 73.3 million were

15 and 24 years of age. (That's 36.7%) Between 2009 and 2015, youth

unemployment increased considerably in the North Africa and the Middle

East, and slightly in East Asia. During the same period, it fell

noticeably in Europe (both within and without the E.U.), and the rest of

the developed world, Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Central and

South America, but remained steady in South Asia. The ILO estimated that

some 475 million jobs will need to be created worldwide by the

mid-2020s in order to appreciably reduce the number of unemployed

youths.

In 2018, as the number of robots at work continued to increase,

the global unemployment rate fell to 5.2%, the lowest in 38 years.

Current trends suggest that developments in artificial intelligence and

robotics will not result in mass unemployment but can actually create

high-skilled jobs. However, in order to take advantage of this

situation, one needs to hone skills that machines have not yet mastered,

such as teamwork and effective communication.

By analyzing data from the United Nations and the Global Talent

Competitive Index, KDM Engineering found that as of 2019, the top five

countries for international high-skilled workers are Switzerland,

Singapore, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Sweden. Factors

taken into account included the ability to attract high-skilled foreign

workers, business-friendliness, regulatory environment, the quality of

education, and the standard of living. Switzerland is best at retaining

talents due to its excellent quality of life. Singapore is home to a

world-class environment for entrepreneurs. And the United States offers

the most opportunity for growth due to the sheer size of its economy and

the quality of higher education and training. As of 2019, these are also some of the world's most competitive economies, according to the World Economic Forum

(WEF). In order to determine a country or territory's economic

competitiveness, the WEF considers factors such as the trustworthiness

of public institutions, the quality of infrastructure, macro-economic

stability, the quality of healthcare, business dynamism, labor market

efficiency, and innovation capacity.

In Asia

Statistics from the International Monetary Fund

(IMF) reveal that between 2014 and 2019, Japan's unemployment rate went

from about 4% to 2.4% and China's from almost 4.5% to 3.8%. These are

some of the lowest rates among the largest economies of the world.

According to IMF, "Vietnam is at risk of growing old before it grows rich." The share of working-age Vietnamese peaked in 2011, when the country's annual GDP per capita at purchasing power parity was $5,024, compared to $32,585 for South Korea, $31,718 for Japan, and $9,526 for China.

In Europe

Young Germans protesting youth unemployment at a 2014 event

Economic prospects for some millennials have declined largely due to the Great Recession in the late 2000s.

Several governments have instituted major youth employment schemes out

of fear of social unrest due to the dramatically increased rates of youth unemployment. In Europe, youth unemployment levels were very high (56% in Spain, 44% in Italy, 35% in the Baltic states, 19% in Britain

and more than 20% in many more countries). In 2009, leading

commentators began to worry about the long-term social and economic

effects of the unemployment.

A variety of names have emerged in various European countries hard hit following the financial crisis of 2007–2008 to designate young people with limited employment and career prospects.

These groups can be considered to be more or less synonymous with

millennials, or at least major sub-groups in those countries. The Generation of €700 is a term popularized by the Greek mass media and refers to educated Greek twixters of urban centers who generally fail to establish a career.

In Greece, young adults are being "excluded from the labor market" and

some "leave their country of origin to look for better options". They

are being "marginalized and face uncertain working conditions" in jobs

that are unrelated to their educational background, and receive the

minimum allowable base salary of €700 per month. This generation evolved in circumstances leading to the Greek debt crisis and some participated in the 2010–2011 Greek protests. In Spain, they are referred to as the mileurista (for €1,000 per month), in France "The Precarious Generation," and as in Spain, Italy also has the "milleurista"; generation of €1,000 (per month).

Between 2009 and 2018, about half a million Greek youths left

their country in search of opportunities elsewhere, and this phenomenon

has exacerbated the nation's demographic problem. Such brain drains

are rare among countries with good education systems. Greek millennials

benefit from tuition-free universities but suffer from their

government's mishandling of taxes and excessive borrowing. Greek youths

typically look for a career in finance in the United Kingdom, medicine

in Germany, engineering in the Middle East,

and information technology in the United States. Many also seek

advanced degrees abroad in order to ease the visa application process.

In 2016, research from the Resolution Foundation

found millennials in the United Kingdom earned £8,000 less in their 20s

than Generation X, describing millennials as "on course to become the

first generation to earn less than the one before".

Millennials

are the most highly educated and culturally diverse group of all

generations, and have been regarded as hard to please when it comes to

employers.

To address these new challenges, many large firms are currently

studying the social and behavioral patterns of millennials and are

trying to devise programs that decrease intergenerational estrangement,

and increase relationships of reciprocal understanding between older

employees and millennials. The UK's Institute of Leadership & Management researched the gap in understanding between millennial recruits and their managers in collaboration with Ashridge Business School.

The findings included high expectations for advancement, salary and for

a coaching relationship with their manager, and suggested that

organizations will need to adapt to accommodate and make the best use of

millennials. In an example of a company trying to do just this, Goldman Sachs conducted training programs that used actors to portray millennials who assertively sought more feedback, responsibility,

and involvement in decision making. After the performance, employees

discussed and debated the generational differences which they saw played

out. In 2014, millennials were entering an increasingly multi-generational workplace.

Even though research has shown that millennials are joining the

workforce during a tough economic time, they still have remained

optimistic, as shown when about nine out of ten millennials surveyed by

the Pew Research Center said that they currently have enough money or that they will eventually reach their long-term financial goals.

Statistics from the International Monetary Fund

(IMF) reveal that between 2014 and 2019, unemployment rates fell in

most of the world's major economies, many of which in Europe. Although

the unemployment rates of France and Italy remained relatively high,

they were markedly lower than previously. Meanwhile, the German

unemployment rate dipped below even that of the United States, a level

not seen since the German reunification almost three decades prior. Eurostat

reported in 2019 that overall unemployment rate across the European

Union dropped to its lowest level since January 2000, at 6.2% in August,

meaning about 15.4 million people were out of a job. The Czech Republic

(3%), Germany (3.1%) and Malta (3.3%) enjoyed the lowest levels of

unemployment. Member states with the highest unemployment rates were

Italy (9.5%), Spain (13.8%), and Greece (17%). Countries with higher

unemployment rates compared to 2018 were Denmark (from 4.9% to 5%),

Lithuania (6.1% to 6.6%), and Sweden (6.3% to 7.1%).

In November 2019, the European Commission

expressed concern over the fact that some member states have "failed to

put their finances in order." Belgium, France, and Spain had a debt-to-GDP ratio

of almost 100% each while Italy's was 136%. Under E.U. rules, member

nations must take steps to decrease public debt if it exceeds 60% of

GDP. The Commission commended Greece for making progress in economic

recovery.

Top five professions with insufficient workers in the European Union in the late 2010s.

According to the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop), the European Union in the late 2010s suffers from shortages of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) specialists (including information and communications technology (ICT)

professionals), medical doctors, nurses, midwives and schoolteachers.

However, the picture varies depending on the country. In Italy,

environmentally friendly architecture is in high demand. Estonia and

France are running short of legal professionals. Ireland, Luxembourg,

Hungary, and the United Kingdom need more financial experts. All member

states except Finland need more ICT specialists, and all but Belgium,

Greece, Spain, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal and the

United Kingdom need more teachers. The supply of STEM graduates has been

insufficient because the dropout rate

is high and because of an ongoing brain drain from some countries. Some

countries need more teachers because many are retiring and need to be

replaced. At the same time, Europe's aging population necessitates the

expansion of the healthcare sector. Disincentives for (potential)

workers in jobs in high demand include low social prestige, low

salaries, and stressful work environments. Indeed, many have left the

public sector for industry while some STEM graduates have taken non-STEM

jobs.

Even though pundits

predicted that the uncertainty due to the 2016 Brexit Referendum would

cause the British economy to falter or even fall into a recession, the

unemployment rate has dipped below 4% while real wages have risen

slightly in the late 2010s, two percent as of 2019. In particular,

medical doctors and dentists saw their earnings bumped above the

inflation rate in July 2019. Despite the fact that the government

promised to an increase in public spending (£13 billion, or 0.6% of GDP)

in September 2019, public deficit continues to decline, as it has since

2010. Nevertheless, uncertainty surrounding Britain's international

trade policy suppressed the chances of an export boom despite the

depreciation of the pound sterling. According to the Office for National Statistics, the median income of the United Kingdom in 2018 was £29,588.

Since joining the European Union during the 2007 enlargement of the European Union,

Bulgaria has seen a significant portion of its population, many of whom

young and educated, leave for better opportunities elsewhere, notably

Germany. While the government has failed to keep reliable statistics,

economists have estimated that at least 60,000 Bulgarians leave their

homeland each year. 30,000 moved to Germany in 2017. As of 2019, an

estimated 1.1 million Bulgarians lived abroad. Bulgaria had a population

of about seven million in 2018, and this number is projected to

continue to decline not just due to low birth rates but also to

emigration.

In Canada

In Canada, the youth unemployment rate in July 2009 was 16%, the highest in 11 years. Between 2014 and 2019, Canada's overall unemployment rate fell from about 7% to below 6%.

However, a 2018 survey by accounting and advisory firm BDO Canada found

that 34% of millennials felt "overwhelmed" by their non-mortgage debt.

For comparison, this number was 26% for Generation X and 13% for the

Baby Boomers. Canada's average non-mortgage debt was CAN$20,000 in 2018.

About one in five millennials were delaying having children because of

financial worries. Many Canadian millennial couples are also struggling

with their student loan debts.

Ottawa became a magnet for millennials in the late 2010s.

Despite expensive housing costs, Canada's largest cities, Vancouver,

Toronto, and Montreal, continue to attract millennials thanks to their

economic opportunities and cultural amenities. Research by the Royal Bank of Canada

(RBC) revealed that for every person in the 20-34 age group who leaves

the nation's top cities, Toronto gains seven while Vancouver and

Montreal gain up to a dozen each. In fact, there has been a surge in the

millennial populations of Canada's top three cities between 2015 and

2018. However, millennials' rate of home ownership will likely drop as

increasing numbers choose to rent instead.

By 2019, however, Ottawa emerged as a magnet for millennials with its

strong labor market and comparatively low cost of living, according to a

study by Ryerson University. Many of the millennials relocating to the

nation's capital were above the age of 25, meaning they were more likely

to be job seekers and home buyers rather than students.

An average Canadian home was worth CAN$484,500 in 2018. Despite

government legislation (mortgage stress test rules), such a price was

quite high compared to some decades before. Adjusted for inflation, it

was CAN$210,000 in 1976. Paul Kershaw of the University of British

Columbia calculated that the average amount of extra money needed for a

down payment in the late 2010s compared to one generation before was

equivalent to eating 17 avocado toasts each day for ten years.

Meanwhile, the option of renting in a large city is increasingly out of

reach for many young Canadians. In 2017, the average rent in Canada

cost $947 a month, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

(CMHC). But, as is always the case in real-estate, location matters. An

average two-bedroom apartment cost CAN$1,552 per month in Vancouver and

CAN$1,404 per month in Toronto, with vacancy rates at about one

percent.

Canada's national vacancy rate was 2.4% in 2018, the lowest since 2009.

New supply – rental apartment complexes that are newly completed or

under construction – has not been able to keep up with rising demand.

Besides higher prices, higher interest rates and stricter mortgage rules

have made home ownership more difficult. International migration

contributes to rising demand for housing, especially rental apartments,

according to the CMHC, as new arrivals tend to rent rather than

purchase. Moreover, a slight decline in youth unemployment in 2018 also

drove up demand. While the Canadian housing market is growing, this growth is detrimental to the financial well-being of young Canadians.

In 2019, Canada's net public debt was CAN$768 billion. Meanwhile,

U.S. public debt amounted to US$22 trillion. The Canadian federal

government's official figure for the debt-to-GDP ratio was 30.9%.

However, this figure left out debts from lower levels of government.

Once these were taken into account, the figure jumped to 88%, according

to the International Monetary Fund. For comparison, that number was

237.5% for Japan, 106.7% for the United States, and 99.2% for France.

Canada's public debt per person was over CAN$18,000. For Americans, it

was US$69,000.

Since the Great Recession, Canadian households have accumulated

significantly more debt. According to Statistics Canada, the national

debt-to-disposable income ratio was 175% in 2019. It was 105% in the

U.S. Meanwhile, the national median mortgage debt rose from CAN$95,400

in 1999 to CAN$190,000 in 2016 (in 2016 dollars). Numbers are much

higher in the Greater Toronto Area, Vancouver, and Victoria, B.C.

A 2018 survey by Abacus Data

of 4,000 Canadian millennials found that 80% identified as members of

the middle class, 55% had pharmaceutical insurance, 53% dental

insurance, 36% a Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP), and 29% an employer-sponsored pension plan.

A number of millennials have opted to save their money and retire early

while traveling rather than settling in an expensive North American

city. According to them, such a lifestyle costs less than living in a

large city.

In the United States

Employment and finances

The youth unemployment rate in the U.S. reached a record 19% in July 2010 since the statistic started being gathered in 1948. Underemployment

is also a major factor. In the U.S. the economic difficulties have led

to dramatic increases in youth poverty, unemployment, and the numbers of

young people living with their parents. In April 2012, it was reported that half of all new college graduates in the US were still either unemployed or underemployed. It has been argued that this unemployment rate and poor economic situation has given millennials a rallying call with the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement. However, according to Christine Kelly, Occupy is not a youth movement and has participants that vary from the very young to very old.

Millennials have benefited the least from the economic recovery following the Great Recession,

as average incomes for this generation have fallen at twice the general

adult population's total drop and are likely to be on a path toward

lower incomes for at least another decade. According to a Bloomberg L.P., "Three and a half years after the worst recession since the Great Depression,

the earnings and employment gap between those in the under-35

population and their parents and grandparents threatens to unravel the

American dream of each generation doing better than the last. The

nation's younger workers have benefited least from an economic recovery

that has been the most uneven in recent history."

In 2015, millennials in New York City were reported as earning 20% less

than the generation before them, as a result of entering the workforce

during the great recession.

Despite higher college attendance rates than Generation X, many were

stuck in low-paid jobs, with the percentage of degree-educated young

adults working in low-wage industries rising from 23% to 33% between

2000 and 2014.

According to a 2019 TD Ameritrade survey of 1,015 U.S. adults

aged 23 and older with at least US$10,000 in investable assets, two

thirds of people aged 23 to 38 (Millennials) felt they were not saving

enough for retirement, and the top reason why was expensive housing

(37%). This was especially true for Millennials with families. 21% said

student debt prevented them from saving for the future. For comparison,

this number was 12% for Generation X and 5% for the Baby Boomers. While millennials are well known for taking out large amounts of student loans, these are actually not

their main source of non-mortgage personal debt, but rather credit card

debt. According to a 2019 Harris poll, the average non-mortgage

personal debt of millennials was US$27,900, with credit card debt

representing the top source at 25%. For comparison, mortgages were the

top source of debt for the Baby Boomers and Generation X (28% and 30%,

respectively) and student loans for Generation Z (20%).

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the unemployment rate in September 2019 was 3.5%, a number not seen since December 1969. For comparison, unemployment attained a maximum of 10% after the Great Recession in October 2009. At the same time, labor participation remained steady and most job growth tended to be full-time positions.

Economists generally consider a population with an unemployment rate

lower than 4% to be fully employed. In fact, even people with

disabilities or prison records are getting hired.

Between June 2018 and June 2019, the U.S. economy added a minimum of

56,000 jobs (February 2019) and a maximum of 312,000 jobs (January

2019). The average monthly job gain between the same period was about 213,600.

Tony Bedikian, managing director and head of global markets at Citizens

Bank, said this is the longest period of economic expansion on record. At the same time, wages continue to grow, especially for low-income earners. On average, they grew by 2.7% in 2016 and 3.3% in 2018.

However, the Pew Research Center found that the average wage in the

U.S. in 2018 remained more or less the same as it was in 1978, when the

seasons and inflation are taken into consideration. Real wages grew only

for the top 90th percentile of earners and to a lesser extent the 75th

percentile (in 2018 dollars). Nevertheless, these developments ease fears of an upcoming recession.

Moreover, economists believe that job growth could slow to an average

of just 100,000 per month and still be sufficient to keep up with

population growth and keep economic recovery going. As long as firms keep hiring and wages keep growing, consumer spending should prevent another recession. Millennials are expected to make up approximately half of the U.S. workforce by 2020.

U.S.

states by the percentage of the over 25-year-old population with

bachelor's degrees according to the U.S. Census Bureau American

Community Survey 2013–2017 5-Year Estimates. States with above average

shares of degree holders are in full orange.

Human capital is the engine of economic growth. With this in mind, urban researcher Richard Florida and his collaborators analyzed data from the U.S. Census

from between 2012 and 2017 and found that the ten cities with the

largest shares of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher are Seattle

(62.6%), San Francisco, the District of Columbia, Raleigh, Austin,

Minneapolis, Portland, Denver, Atlanta, and Boston (48.2%). More

specifically, the ten cities with the largest shares of people with

graduate degrees are the District of Columbia (33.4%), Seattle, San

Francisco, Boston, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Portland, Denver, Austin, and

San Diego (18.5%). These are the leading information technology hubs of

the United States. Cities with the lowest shares of college graduates

tend to be from the Rust Belt, such as Detroit, Memphis, and Milwaukee,

and the Sun Belt, such as Las Vegas, Fresno, and El Paso. Meanwhile, the

ten cities with the fastest growth in the shares of college-educated

adults are Miami (46.3%), Austin, Fort Worth, Las Vegas, Denver,

Charlotte, Boston, Mesa, Nashville, and Seattle (25.1%). More

specifically, those with the fastest growing shares of adults with

graduate degrees are Miami (47.1%), Austin, Raleigh, Charlotte, San

Jose, Omaha, Seattle, Fresno, Indianapolis, and Sacramento (32.0%).

Florida and his team also found, using U.S. Census data between

2005 and 2017, an increase in employment across the board for members of

the "creative class" – people in education, healthcare, law, the arts,

technology, science, and business, not all of whom have a university

degree – in virtually all U.S. metropolitan areas with a population of a

million or more. Indeed, the total number of the creative class grew

from 44 million in 2005 to over 56 million in 2017. Florida suggested

that this could be a "tipping point" in which talents head to places

with a high quality of life yet lower costs of living than

well-established creative centers, such as New York City and Los

Angeles, what he called the "superstar cities."

According to the Department of Education,

people with technical or vocational trainings are slightly more likely

to be employed than those with a bachelor's degree and significantly

more likely to be employed in their fields of specialty. The United

States currently suffers from a shortage of skilled tradespeople.

As of 2019, the most recent data from the U.S. government reveals that

there are over half a million vacant manufacturing jobs in the country, a

record high, thanks to an increasing number of Baby Boomers entering

retirement. But in order to attract new workers to overcome this "Silver Tsunami,"

manufacturers need to debunk a number of misconceptions about their

industries. For example, the American public tends to underestimate the

salaries of manufacturing workers. Nevertheless, the number of people

doubting the viability of American manufacturing has declined to 54% in

2019 from 70% in 2018, the L2L Manufacturing Index measured.

After the Great Recession, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs

reached a minimum of 11.5 million in February 2010. It rose to

12.8 million in September 2019. It was 14 million in March 2007.

As of 2019, manufacturing industries made up 12% of the U.S. economy,

which is increasingly reliant on service industries, as is the case for

other advanced economies around the world.

Nevertheless, twenty-first-century manufacturing is increasingly

sophisticated, using advanced robotics, 3D printing, cloud computing,

among other modern technologies, and technologically savvy employees are

precisely what employers need. Four-year university degrees are

unnecessary; technical or vocational training, or perhaps

apprenticeships would do.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the occupations with the highest median annual pay in the United States in 2018 included medical doctors (especially psychiatrists, anesthesiologists, obstetricians and gynecologists, surgeons, and orthodontists), chief executives, dentists, information system managers, chief architects and engineers, pilots and flight engineers, petroleum engineers,

and marketing managers. Their median annual pay ranged from about

US$134,000 (marketing managers) to over US$208,000 (aforementioned

medical specialties). Meanwhile, the occupations with the fastest projected growth rate between 2018 and 2028 are solar cell and wind turbine technicians, healthcare and medical aides, cyber security experts, statisticians, speech-language pathologists, genetic counselors, mathematicians, operations research analysts, software engineers, forest fire inspectors and prevention specialists, post-secondary health instructors, and phlebotomists.

Their projected growth rates are between 23% (medical assistants) and

63% (solar cell installers); their annual median pays range between

roughly US$24,000 (personal care aides) to over US$108,000 (physician

assistants).

Occupations with the highest projected numbers of jobs added between

2018 and 2028 are healthcare and personal aides, nurses, restaurant

workers (including cooks and waiters), software developers, janitors and cleaners, medical assistants, construction workers, freight laborers, marketing researchers and analysts, management analysts, landscapers and groundskeepers, financial managers, tractor and truck drivers, and medical secretaries.

The total numbers of jobs added ranges from 881,000 (personal care

aides) to 96,400 (medical secretaries). Annual median pays range from

over US$24,000 (fast-food workers) to about US$128,000 (financial

managers).

Despite economic recovery and despite being more likely to have a

bachelor's degree or higher, millennials are at a financial

disadvantage compared to the Baby Boomers and Generation X because of

the Great Recession and expensive higher education. Income has become

less predictable due to the rise of short-term and freelance positions.

According to a 2019 report from the non-partisan non-profit think tank

New America, a household headed by a person under 35 in 2016 had an

average net worth of almost US$11,000, compared to US$20,000 in 1995.

According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve,

an average millennial (20 to 35 in 2016) owned US$162,000 of assets,

compared to US$198,000 for Generation X at the same age (20 to 35 in

2001). Risk management specialist and business economist Olivia S. Mitchell

of the University of Pennsylvania calculated that in order to retire at

50% of their last salary before retirement, millennials will have to

save 40% of their incomes for 30 years. She told CNBC, "Benefits from

Social Security are 76% higher if you claim at age 70 versus 62, which

can substitute for a lot of extra savings." Maintaining a healthy

lifestyle – avoiding smoking, over-drinking, and sleep deprivation –

should prove beneficial.

Housing

A

rural county's chances of having a performing arts organization is 60%

higher if it is located near a national park or forest. Pictured: The Redwood National and State Parks, California.

Economist Tim Wojan and his colleagues at the Economic Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

analyzed 11,000 businesses using data collected in 2014 and classified

them into three groups: substantive innovators, nominal innovators, and

non-innovators. They found that 20% of the establishments hailed from

rural areas compared to 30% from urban areas. In addition, large

innovative firms were more likely to be found in rural areas while small

and medium firms tended to come from the metropolitan areas. This is

because large patent-intensive manufacturing firms – such as those

manufacturing chemicals, electronic components, automotive parts, or

medical equipment – were generally based in rural areas while those that

provide services tend to cluster in the cities. Nevertheless, rural

creative centers tend to be relatively close to large urban centers. The

National Endowment for the Arts

reported in 2017 that a rural county's probability of having a

performing arts organization increased by 60% if it is located near a

forest or a national park.

Urban researcher Richard Florida concluded that there is no compelling

reason to believe that rural America is not as innovative as urban

America.

Nevertheless, despite the availability of affordable housing, and

broadband Internet, the possibility of telecommuting, the reality of

high student loan debts and the stereotype of living in their parents'

basement, millennials were steadily leaving rural counties for urban

areas for lifestyle and economic reasons in the early 2010s. At that time, millennials were responsible for the so-called "back-to-the-city" trend.

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of Americans living in urban areas

grew from 79% to 80.7% while that in rural areas dropped from 21% to

19.3%. At the same time, many new cities were born, especially in the

Midwest, and others, such as Charlotte, North Carolina, and Austin,

Texas, were growing enormously.

According to demographer William Frey of the Brookings Institution, the

population of young adults (18-34 years of age) in U.S. urban cores

increased 4.9% between 2010 and 2015, the bulk of which can be

attributed to ethnic-minority millennials, especially in places like

Atlanta, Boston, Houston, San Antonio, and San Francisco. In fact, this

demographic trend was making American cities and their established

suburbs more ethnically diverse. On the other hand, white millennials

were the majority in emerging suburbs and exurbs.

Mini-apartments, initially found mainly in Manhattan, became more and

more common in other major urban areas as a strategy for dealing with

high population density and high demand for housing, especially among

people living alone. The number of single-person households in the U.S.

reached 27% in 2010 from 8% in 1940 and 18% in 1970; in places such as

Atlanta, Cincinnati, Denver, Pittsburgh, Seattle, St. Louis and

Washington, D.C, it can even exceed 40%, according to Census data. The

size of a typical mini-apartment is 300 square feet (28 square meters),

or roughly the size of a standard garage and one eighth the size of an

average single-family home in the U.S. as of 2013. Many young city

residents were willing to give up space in exchange for living in a

location they liked. Such apartments are also common in Tokyo and some

European capitals.

Data from the Census Bureau reveals that in 2018, 33.7% of American

adults below the age of 35 owned a home, compared to the national

average of almost 64%.

Yet by the late 2010s, things changed. Like older generations,

millennials reevaluate their life choices as they age. Millennials no

longer felt attracted by cosmopolitan metropolitan areas the way they

once did. A 2018 Gallup poll found that despite living in a highly

urbanized country, most Americans would rather live in rural counties

than the cities. While rural America lacked the occupational diversity

offered by urban America, multiple rural counties can still match one

major city in terms of economic opportunities. In addition, rural towns

suffered from shortages of certain kinds of professionals, such as

medical doctors, and young people moving in, or back, could make a

difference for both themselves and their communities. The slower pace of

life and lower costs of living were both important.

Young Americans are leaving the cities for the suburbs in large numbers. Pictured: Munster, Indiana (near Chicago, Illinois).

By analyzing U.S. Census data, demographer William H. Frey at the Brookings Institution found that, following the Great Recession,

American suburbs grew faster than dense urban cores. For example, for

every one person who moved to New York City, five moved out to one of

its suburbs. Data released by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2017 revealed

that Americans aged 25–29 were 25% more likely to move from a city to a

suburb than the other way around; for older millennials, that number was

50%. Economic recovery and easily obtained mortgages help explain this

phenomenon.

Millennial homeowners are more likely to be in the suburbs than the

cities. This trend will likely continue as more and more millennials

purchase a home. 2019 was the fourth year in a row where the number of

millennials living in the major American cities declined measurably. In 2018, 80,000 millennials left the nation's largest cities.

While 14% of the U.S. population relocate at least once each

year, Americans in their 20s and 30s are more likely to move than

retirees, according to Frey. Besides the cost of living, including

housing costs, people are leaving the big cities in search of warmer

climates, lower taxes, better economic opportunities, and better school

districts for their children.

Places in the South and Southwestern United States are especially

popular. In some communities, millennials and their children are moving

in so quickly that schools and roads are becoming overcrowded. This

rising demand pushes prices upwards, making affordable housing options

less plentiful.

Historically, between the 1950s and 1980s, Americans left the cities

for the suburbs because of crime. Suburban growth slowed because of the

Great Recession but picked up pace afterwards.

According to the Brookings Institution, overall, American cities with

the largest net losses in their millennial populations were New York

City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, while those with the top net gains were

Houston, Denver, and Dallas. According to Census data, Los Angeles County in particular lost 98,608 people in 2018, the single biggest loss in the nation. Moving trucks (U-Haul) are in extremely high demand in the area.

High taxes and high cost of living are also reasons why people are leaving entire states behind.

As is the case with cities, young people are the most likely to

relocate. For example, a 2019 poll by Edelman Intelligence of 1,900

residents of California found that 63% of millennials said they were

thinking about leaving the Golden State and 55% said they wanted to do

so within five years. 60% of millennials said the reason why they

wanted to move as the cost and availability of housing. In 2018, the

median home price in California was US$547,400, about twice the national

median. California also has the highest marginal income tax rate of all

U.S. states, 12.3%, plus a subcharge of 1% for those earning a million

dollars a year or more. Popular destinations include Oregon, Nevada,

Arizona, and Texas, according to California's Legislative Analyst's

Office. By analyzing data provided by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), finance company SmartAsset

found that for wealthy millennials, defined as those no older than 35

years of age earning at least US$100,000 per annum, the top states of

departure were New York, Illinois, Virginia, Massachusetts, and

Pennsylvania, while the top states of destination were California,

Washington State, Texas, Colorado, and Florida.[214]

SmartAsset also found that the cities with the largest percentages of

millennial homeowners in 2018 were Anchorage, AK; Gilbert and Peoria,

AZ; Palmdale, Moreno Valley, Hayward, and Garden Grove, CA; Cape Floral,

FL; Sioux Falls, SD; and Midland, TX. Among these cities, millennial

home-owning rates were between 56.56% (Gilbert, AZ) and 34.26% (Hayward,

CA).

The median price of a home purchased by millennials in 2019 was

$256,500, compared to $160,600 for Generation Z. Broadly speaking, the

two demographic cohorts are migrating in opposite directions, with the

millennials moving North and Generation Z going South.

Education

For information on public support for higher education (for domestic students) in the OECD in 2011, see chart below.

In continental Europe

In Sweden, universities are tuition-free, as is the case in Norway,

Denmark, Iceland, and Finland. However, Swedish students typically

graduate very indebted due to the high cost of living in their country,

especially in the large cities such as Stockholm. The ratio of debt to

expected income after graduation for Swedes was about 80% in 2013. In

the U.S., despite incessant talk of student debt reaching epic

proportions, that number stood at 60%. Moreover, about seven out of

eight Swedes graduate with debt, compared to one half in the U.S. In the

2008–9 academic year, virtually all Swedish students take advantage of

state-sponsored financial aid packages from a govern agency known as the

Centrala Studiestödsnämnden

(CSN), which include low-interest loans with long repayment schedules

(25 years or until the student turns 60). In Sweden, student aid is

based on their own earnings whereas in some other countries, such as

Germany or the United States, such aid is premised on parental income as

parents are expected to help foot the bill for their children's

education. In the 2008–9 academic year, Australia, Austria, Japan, the

Netherlands, and New Zealand saw an increase in both the average tuition

fees of their public universities for full-time domestic students and

the percentage of students taking advantage of state-sponsored student

aid compared to 1995. In the United States, there was an increase in the

former but not the latter.

In 2005, judges in Karlsruhe, Germany, struck down a ban on

university fees as unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the

constitutional right of German states to regulate their own higher

education systems. This ban was introduced in order to ensure equality

of access to higher education regardless of socioeconomic class.

Bavarian Science Minister Thomas Goppel told the Associated Press, "Fees

will help to preserve the quality of universities." Supporters of fees

argued that they would help ease the financial burden on universities

and would incentivize students to study more efficiently, despite not

covering the full cost of higher education, an average of €8,500 as of

2005. Opponents believed fees would make it more difficult for people to

study and graduate on time.

Germany also suffered from a brain drain, as many bright researchers

moved abroad while relatively few international students were interested

in coming to Germany. This has led to the decline of German research

institutions.

In English-speaking countries

In the 1990s, due to a combination of financial hardship and the fact

that universities elsewhere charged tuition, British universities

pressed the government to allow them to take in fees. A nominal tuition

fee of £1,000 was introduced in autumn 1998. Because not all parents

would be able to pay all the fees in one go, monthly payment options,

loans, and grants were made available. Some were concerned that making

people pay for higher education may deter applicants. This turned out

not to be the case. The number of applications fell by only 2.9% in

1998, and mainly due to mature students rather than 18-year-olds.

In 2012, £9,000 worth of student fees were introduced. Despite

this, the number of people interested in pursuing higher education grew

at a faster rate than the UK population. In 2017, almost half of Britons

have received higher education by the age of 30. Prime Minister Tony

Blair introduced the goal of having half of young Britons having a

university degree in 1999, though he missed the 2010 deadline. Demand

for higher education in the United Kingdom remains strong, driven by the

need for high-skilled workers from both the public and private sectors.

There is, however, a widening gender gap. As of 2017, women were more

likely to attend or have attended university than men, 55% to 43%, a 12%

difference.

In Australia, university tuition fees were introduced in 1989.

Regardless, the number of applicants has risen considerably. By the

1990s, students and their families were expected to pay 37% of the cost,

up from a quarter in the late 1980s. The most expensive subjects were

law, medicine, and dentistry, followed by the natural sciences, and then

by the arts and social studies. Under the new funding scheme, the

Government of Australia also capped the number of people eligible for

higher education, enabling schools to recruits more well-financed

(though not necessarily bright) students.

According to the Pew Research Center, 53% of American Millennials

attended or were enrolled in university in 2002. The number of young

people attending university was 44% in 1986.

Historically, university students were more likely to be male than

female. The difference was especially great during the second half of

the twentieth century, when enrollment rose dramatically compared to the

1940s. This trend continues into the twenty-first century. But things

started to change by the turn of the new millennium. By the late 2010s,

the situation has reversed. Women are now more likely to enroll in

university than men. In 2018, upwards of one third of each sex is a

university student.

In the United States today, high school students are generally

encouraged to attend college or university after graduation while the

options of technical school and vocational training are often neglected.

Historically, high schools separated students on career tracks, with

programs aimed at students bound for higher education and those bound

for the workforce. Students with learning disabilities or behavioral

issues were often directed towards vocational or technical schools. All

this changed in the late 1980s and early 1990s thanks to a major effort

in the large cities to provide more abstract academic education to

everybody. The mission of high schools became preparing students for

college, referred to as "high school to Harvard."

However, this program faltered in the 2010s, as institutions of higher

education came under heightened skepticism due to high costs and

disappointing results. People became increasingly concerned about debts

and deficits. No longer were promises of educating "citizens of the

world" or estimates of economic impact coming from abstruse calculations

sufficient. Colleges and universities found it necessary to prove their

worth by clarifying how much money from which industry and company

funded research, and how much it would cost to attend.

Because jobs (that suited what one studied) were so difficult to

find in the few years following the Great Recession, the value of

getting a liberal arts degree

and studying the humanities at an American university came into

question, their ability to develop a well-rounded and broad-minded

individual notwithstanding. As of 2019, the total college debt has exceeded US$1.5 trillion, and two out of three college graduates are saddled with debt.

The average borrower owes US$37,000, up US$10,000 from ten years

before. A 2019 survey by TD Ameritrade found that over 18% of

Millennials (and 30% of Generation Z) said they have considered taking a

gap year between high school and college.

In 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published research (using data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances)

demonstrating that after controlling for race and age cohort families

with heads of household with post-secondary education and who born

before 1980 there have been wealth and income premiums, while for

families with heads of household with post-secondary education but born

after 1980 the wealth premium has weakened to point of statistical insignificance (in part because of the rising cost of college)

and the income premium while remaining positive has declined to