Ruins of forecourt of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, where know thyself was once said to be inscribed

A memento mori mosaic from excavations in the convent of San Gregorio in Rome, featuring the Greek motto.

Allegorical painting from the 17th century with text Nosce te ipsum

The Ancient Greek aphorism "know thyself" (Greek: γνῶθι σεαυτόν, transliterated: gnōthi seauton; also ... σαυτόν … sauton with the ε contracted), is one of the Delphic maxims and was the first of three maxims inscribed in the pronaos (forecourt) of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi according to the Greek writer Pausanias (10.24.1). The two maxims that followed "know thyself" were "nothing to excess" and "surety brings ruin". In Latin the phrase, "know thyself," is given as nosce te ipsum or temet nosce.

The maxim, or aphorism, "know thyself" has had a variety of

meanings attributed to it in literature, and over time, as in early

ancient Greek the phrase meant "know thy measure."

Attribution

The Greek aphorism has been attributed to at least the following ancient Greek sages:

- Bias of Priene

- Chilon of Sparta

- Cleobulus of Lindus

- Heraclitus

- Myson of Chenae

- Periander

- Pittacus of Mytilene

- Pythagoras

- Socrates

- Solon of Athens

- Thales of Miletus

Diogenes Laërtius attributes it to Thales (Lives I.40), but also notes that Antisthenes in his Successions of Philosophers attributes it to Phemonoe,

a mythical Greek poet, though admitting that it was appropriated by

Chilon. In a discussion of moderation and self-awareness, the Roman poet

Juvenal quotes the phrase in Greek and states that the precept descended e caelo (from heaven) (Satires 11.27). The 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia the Suda recognized Chilon and Thales as the sources of the maxim "Know Thyself."

The authenticity of all such attributions is doubtful; according

to Parke and Wormell (1956), "The actual authorship of the three maxims

set up on the Delphian temple may be left uncertain. Most likely they

were popular proverbs, which tended later to be attributed to particular

sages."

Usage

Listed chronologically:

By Aeschylus

The ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus uses the maxim "know thyself" in his play Prometheus Bound.

The play about a mythological sequence, thereby places the maxim within

the context of Greek mythology. In this play, the demi-god Prometheus

first rails at the Olympian gods, and against what he believes to be

the injustice of his having been bound to a cliffside by Zeus, king of

the Olympian gods. The demi-god Oceanus comes to Prometheus to reason with him, and cautions him that he should "know thyself".

In this context, Oceanus is telling Prometheus that he should know

better than to speak ill of the one who decides his fate and

accordingly, perhaps he should better know his place in the "great order

of things."

By Socrates

One of Socrates's students, the historian Xenophon, described some of the instances of Socrates's use of the Delphic maxim 'Know Thyself' in his history titled: Memorabilia.

In this writing, Xenophon portrayed his teacher's use of the maxim as

an organizing theme for Socrates's lengthy dialogue with Euthydemus.

By Plato

Plato,

another student of Socrates, employs the maxim 'Know Thyself'

extensively by having the character of Socrates use it to motivate his

dialogues. Benjamin Jowett's index to his translation of the Dialogues of Plato lists six dialogues which discuss or explore the Delphic maxim: 'know thyself.' These dialogues (and the Stephanus numbers indexing the pages where these discussions begin) are Charmides (164D), Protagoras (343B), Phaedrus (229E), Philebus (48C), Laws (II.923A), Alcibiades I (124A, 129A, 132C).

In Plato's Charmides,

Critias argues that "succeeding sages who added 'never too much,' or,

'give a pledge, and evil is nigh at hand,' would appear to have so

misunderstood them; for they imagined that 'know thyself!' was a piece

of advice which the god gave, and not his salutation of the worshippers

at their first coming in; and they dedicated their own inscription under

the idea that they too would give equally useful pieces of advice."

In Critias' opinion 'know thyself!' was an admonition to those

entering the sacred temple to remember or know their place and that

'know thyself!' and 'be temperate!' are the same. In the balance of the Charmides, Plato has Socrates lead a longer inquiry as to how we may gain knowledge of ourselves.

In Plato's Phaedrus,

Socrates uses the maxim 'know thyself' as his explanation to Phaedrus

to explain why he has no time for the attempts to rationally explain

mythology or other far flung topics. Socrates says, "But I have no

leisure for them at all; and the reason, my friend, is this: I am not

yet able, as the Delphic inscription has it, to know myself; so it seems

to me ridiculous, when I do not yet know that, to investigate

irrelevant things."

In Plato's Protagoras, Socrates lauds the authors of pithy and concise sayings delivered precisely at the right moment and says that Lacedaemon, or Sparta,

educates its people to that end. Socrates lists the Seven Sages as

Thales, Pittacus, Bias, Solon, Cleobulus, Myson, and Chilon, who he says

are gifted in that Lacedaemonian art of concise words "twisted

together, like a bowstring, where a slight effort gives great force."

Socrates says examples of them are, "the far-famed inscriptions, which

are in all men's mouths,--'Know thyself,' and 'Nothing too much'.".

Having lauded the maxims, Socrates then spends a great deal of time

getting to the bottom of what one of them means, the saying of Pittacus,

'Hard is it to be good.' The irony here is that although the sayings

of Delphi bear 'great force,' it is not clear how to live life in

accordance with their meanings. Although, the concise and broad nature

of the sayings suggests the active partaking in the usage and personal

discovery of each maxim; as if the intended nature of the saying lay not

in the words but the self-reflection and self-referencing of the person

thereof.

In Plato's Philebus dialogue, Socrates refers back to the same usage of 'know thyself' from Phaedrus

to build an example of the ridiculous for Protarchus. Socrates says,

as he did in Phaedrus, that people make themselves appear ridiculous

when they are trying to know obscure things before they know themselves.

Plato also alluded to the fact that understanding 'thyself,' would have

a greater yielded factor of understanding the nature of a human being.

Syllogistically, understanding oneself would enable thyself to have an

understanding of others as a result.

Later usage

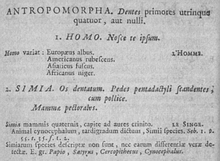

Detail from the 6th edition of Linnaeus' Systema Naturae (1748). "HOMO. Nosce te ipsum."

The Suda, a 10th-century encyclopedia of Greek knowledge, says: "the proverb is applied to those whose boasts exceed what they are", and that "know thyself" is a warning to pay no attention to the opinion of the multitude.

One work by the Medieval philosopher Peter Abelard is entitled Scito te ipsum (“know yourself”) or Ethica.

From 1539 onwards the phrase nosce te ipsum and its Latin variants were often used in the anonymous texts written for anatomical fugitive sheets

printed in Venice as well as for later anatomical atlases printed

throughout Europe. The 1530s fugitive sheets are the first instances in

which the phrase was applied to knowledge of the human body attained

through dissection.

In 1651 Thomas Hobbes used the term nosce teipsum which he translated as 'read thyself' in his famous work, The Leviathan.

He was responding to a popular philosophy at the time that you can

learn more by studying others than you can from reading books. He

asserts that one learns more by studying oneself: particularly the

feelings that influence our thoughts and motivate our actions. As Hobbes

states, "but to teach us that for the similitude of the thoughts and

passions of one man, to the thoughts and passions of another, whosoever

looketh into himself and considereth what he doth when he does think,

opine, reason, hope, fear, etc., and upon what grounds; he shall thereby

read and know what are the thoughts and passions of all other men upon

the like occasions."

In 1734 Alexander Pope

wrote a poem entitled "An Essay on Man, Epistle II", which begins "Know

then thyself, presume not God to scan, The proper study of mankind is

Man."

In 1735 Carl Linnaeus published the first edition of Systema Naturae in which he described humans (Homo) with the simple phrase "Nosce te ipsum".

In 1750 Benjamin Franklin, in his Poor Richard's Almanack,

observed the great difficulty of knowing one's self, with: "There are

three Things extremely hard, Steel, a Diamond, and to know one's self."

In 1754 Jean-Jacques Rousseau lauded the "inscription of the Temple at Delphi" in his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality.

In 1831, Ralph Waldo Emerson

wrote a poem entitled "Γνώθι Σεαυτόν", or Gnothi Seauton ('Know

Thyself'), on the theme of 'God in thee.' The poem was an anthem to

Emerson's belief that to 'know thyself' meant knowing the God which Emerson felt existed within each person.

In 1832 Samuel T. Coleridge

wrote a poem entitled "Self Knowledge" in which the text centers on the

Delphic maxim 'Know Thyself' beginning, 'Gnôthi seauton!--and is this

the prime And heaven-sprung adage of the olden time!--' and ending with

'Ignore thyself, and strive to know thy God!' Coleridge's text

references JUVENAL, xi. 27.

In 1902 Hugo von Hofmannsthal has his 16th-century alter ego in his letter to Francis Bacon mention a book he intended to call Nosce te ipsum.

In 1904 Sarah Ida Shaw and Elanor Dorcas Pond founded the Delta Delta Delta sorority. Part of their motto is Self-Knowledge, Self-Reverence, and Self-Discipline.

The Wachowskis used one of the Latin versions (temet nosce) of this aphorism as inscription over the Oracle's door in their movies The Matrix (1999) and The Matrix Revolutions (2003). The transgender character Nomi in the Netflix show Sense8, again directed by The Wachowskis, has a tattoo on her arm with the Greek version of this phrase.

LiveReal.com published 45 dimensions of the various ways a person can "know themselves."

"Know Thyself" is the motto of Hamilton College, of Lyceum International School (Nugegoda, Sri Lanka) and of İpek University (Ankara, Turkey). The Latin phrase "Nosce te ipsum" is the motto of Landmark College.

Nosce te ipsum is also the motto for the Scottish clan Thompson. It is featured on the family crest or coat of arms.

In the trilogy of novels “Double Exposure” by Piers Anthony,

“Know thyself” plays a major role in the hero/protagonist’s journey.