Mental health in China is a growing issue. Experts have estimated that about 173 million people living in China are suffering from a mental disorder.

The desire to seek treatment is largely hindered by China's strict

social norms (and subsequent stigmas), as well as religious and cultural

beliefs regarding personal reputation and social harmony.

While the Chinese government is committed to expanding mental health

care services and legislation, the country struggles with a lack of

mental health professionals and access to specialists in rural areas.

History

China's first mental institutions were introduced before 1849 by Western missionaries. Missionary and doctor John G. Kerr

opened the first psychiatric hospital in 1898, with the goal of

providing care to people with mental health issues, and treating them in

a more humane way.

In 1949, the country began developing its mental health resources

by building psychiatric hospitals and facilities for training mental

health professionals. However, many community programs were discontinued

during the Cultural Revolution.

In a meeting jointly held by Chinese ministries and the World Health Organization

in 1999, the Chinese government committed to creating a mental health

action plan and a national mental health law, among other measures to

expand and improve care.

The action plan, adopted in 2002, outlined China's priorities of

enacting legislation, educating its people on mental illness and mental

health resources, and developing a stable and comprehensive system of

care.

In 2000, the Minority Health Disparities Research and Education

Act was enacted. This act helped in raising national awareness on health

issues through research, health education, and data collection.

Since 2006, the government's 686 Program has worked to redevelop

community mental health programs and make these the primary resource,

instead of psychiatric hospitals, for people with mental illnesses.

These community programs make it possible for mental health care to

reach rural areas, and for people in these areas to become mental health

professionals. However, despite the improvement in access to

professional treatment, mental health specialists are still relatively

inaccessible to rural populations. The program also emphasizes

rehabilitation, rather than the management of symptoms.

In 2011, the legal institution of China's State Council published

a draft for a new mental health law, which includes new regulations

concerning the rights of patients to not to be hospitalized against

their will.

The draft law also promotes the transparency of patient treatment

management, as many hospitals were driven by financial motives and

disregarded patients' rights. The law, adopted in 2012, stipulates that a

qualified psychiatrist

must make the determination of mental illness; that patients can choose

whether to receive treatment in most cases; and that only those at risk

of harming themselves or others are eligible for compulsory inpatient

treatment. However, Human Rights Watch

has criticized the law. For example, although it creates some rights

for detained patients to request a second opinion from another state

psychiatrists and then an independent psychiatrist, there is no right to

a legal hearing such as a mental health tribunal and no guarantee of legal representation.

Since 1993, WHO has been collaborating with China in the development of a national mental health information system.

Current

Though

China continues to develop its mental health services, it continues to

have a large number of untreated and undiagnosed people with mental

illnesses. The aforementioned intense stigma associated with mental

illness, a lack of mental health professionals and specialists, and

culturally-specific expressions of mental illness may play a role in the

disparity.

Prevalence of mental disorders

Researchers estimate that roughly 173 million people in China have a mental disorder. Over 90 percent of people with a mental disorder have never been treated.

A lack of government data on mental disorders makes it difficult to

estimate the prevalence of specific mental disorders, as China has not

conducted a national psychiatric survey since 1993.

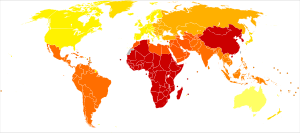

The map of disability-adjusted life years shows the disproportionate impact on the quality of life for persons with bipolar disorder in China and other East Asian countries.

Conducted

between 2001 and 2005, a non-governmental survey of 63,000 Chinese

adults found that 16 percent of the population had a mood disorder, including 6 percent of people with major depressive disorder. Thirteen percent of the population had an anxiety disorder and 9 percent had an alcohol use disorder.

Women were more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder compared to

men, but men were significantly more likely to have an alcohol use

disorder. People living in rural areas were more likely to have major

depressive disorder or alcohol dependence.

In 2007, the Chief of China's National Centre for Mental Health,

Liu Jin, estimated that approximately 50 percent of outpatient

admissions were due to depression.

There is a disproportionate impact on the quality of life for people with bipolar disorder in China and other East Asian countries.

The suicide rate in China was approximately 23 per 100,000 people between 1995 and 1999.

Since then, the rate is thought to have fallen to roughly 7 per 100,000

people, according to government data. WHO states that the rate of

suicide is thought to be three to four times higher in rural areas than

in urban areas. The most common method, poisoning by pesticides,

accounts for 62 percent of incidences.

It is estimated that 18 percent of the Chinese population of over 244 million people believe in Buddhism. Another 22 percent of the population, roughly 294 million people believe in folk religions which are a group of beliefs that share characteristics with Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and shamanism.

Common between all of these philosophical and religious beliefs is an

emphasis on acting harmoniously with nature, with strong morals, and

with a duty to family. Followers of these religions perceive behavior as

being tightly connected with health; illnesses are often thought to be a

result of moral failure or insufficiently honoring one's family in

current or past life. Furthermore, an emphasis on social harmony may

discourage people with mental illness from bringing attention to

themselves and seeking help. They may also refuse to speak about their

mental illness because of the shame it would bring upon themselves and

their family members, who could also be held responsible and experience

social isolation.

Also, reputation might be a factor that prevents individuals from seeking professional help. Good reputations

are highly valued. In a Chinese household, every individual shares the

responsibility of maintaining and raising the family's reputation. It is

believed that mental health will hinder individuals from achieving the

standards and goals- whether academic, social, career-based, or other-

expected from parents. Without reaching the expectations, individuals

are anticipated to bring shame to the family, which will affect the

family's overall reputation. Therefore, mental health issues are seen as

an unacceptable weakness. This perception of mental health disorders

causes individuals to internalize their mental health problems, possibly

worsening them, and making it difficult to seek treatment. Eventually,

it becomes ignored and overlooked by families.

In addition, many of these philosophies teach followers to accept one's fate.

Consequently, people with mental disorders may be less inclined to seek

medical treatment because they believe they should not actively try to

prevent any symptoms that may manifest. They may also be less likely to

question the stereotypes associated with people with mental illness, and

instead agreeing with others that they deserve to be ostracized.

Lack of qualified staff

China has 17,000 certified psychiatrists, which is 10 percent of that of other developed countries per capita.

China averages one psychologist for every 83,000 people, and some of

these psychologists are not board-licensed or certified to diagnose

illnesses. Individuals without any academic background in mental health

can obtain a license to counsel, following several months of training

through the National Exam for Psychological Counselors. Many psychiatrists or psychologists study psychology for personal use and do not intend to pursue a career in counseling.

Patients are likely to leave clinics with false diagnoses, and often do

not return for follow-up treatments, which is detrimental to the

degenerative nature of many psychiatric disorders.

The disparity between psychiatric services available between rural and urban areas partially contributes to this statistic, as rural areas have traditionally relied on barefoot doctors

since the 1970s for medical advice. These doctors are one of the few

modes of healthcare able to reach isolated parts of rural China, and are

unable to obtain modern medical equipment, and therefore, unable to

reliably diagnose psychiatric illnesses. Furthermore, the nearest

psychiatric clinic may be hundreds of miles away, and families may be

unable to afford professional psychiatric treatment for the afflicted.

Physical symptoms

Multiple

studies have found that Chinese patients with mental illness report

more physical symptoms compared to Western patients, who tend to report

more psychological symptoms.

For example, Chinese patients with depression are more likely to report

feelings of fatigue and muscle aches instead of feelings of depression.

However, it is unclear whether this occurs because they feel more

comfortable reporting physical symptoms or if depression manifests in a

more physical way among Chinese people.

Chinese Military Mental Health

Overview

Military

mental health has recently become an area of focus and improvement,

particularly in Western countries. For example, in the United States, it

is estimated that about twenty-five percent of active military members

suffer from a mental health problem, such as PTSD, Traumatic Brain

Injury, and depression.

Currently, there are no clear initiatives from the government about

mental health treatment towards military personnel in China.

Specifically, China has been investing in resources towards researching

and understanding how the mental health needs of military members and

producing policies to reinforce the research results.

Background

Research

on the mental health status of active Chinese military men began in the

1980s where psychologists investigated soldiers' experiences in the

plateaus.

The change of emphasis from physical to mental health can be seen in

China's four dominant military academic journals: First Military

Journal, Second Military Journal, Third Military Journal, and Fourth

Military Journal. In the 1980s, researchers mostly focused on the

physical health of soldiers; as the troops' ability to perform their

services declined, the government began looking at their mental health

to provide an explanation for this trend. In the 1990s, research on it

increased with the hope that by improving the mental health of soldiers,

combat effectiveness improves.

Mental health issue can impact active military members'

effectiveness in the army, and can create lasting effects on them after

they leave the military. Plateaus were an area of interest in this sense

because of harsh environmental conditions and the necessity of the

work done with low atmospheric pressure and intense UV radiation.

It was critical to place the military there to stabilize the outskirts

and protect the Chinese citizens who live nearby; this made it one of

the most important jobs in the army, then increasing the pressure on

those who worked in the plateaus. It not only affected the body

physically, like in the arteries, lungs, and back, but caused high

levels of depression in soldiers because of being away from family

members and with limited communication methods. Scientists found that

this may impact their lives as they saw that this population had higher

rates of divorce and unemployment.

Comparatively, assessing the mental health status of the People's

Liberation Army (PLA) is difficult, because military members work a

diverse array of duties over a large landscape. Military members also

play an active part in disaster relief, peacekeeping in foreign lands,

protecting borders, and domestic riot control. In a study of 11,000

soldiers, researchers found that those who work as peacekeepers have

higher levels of depression compared to those in the engineering and

medical departments.

With such diverse military roles over an area of 3.25 million miles, it

is difficult to gauge its impacts on soldiers’ psyche and provide a

single method to address mental health problems.

Researches have increased over the last two decades, but the

studies still lack a sense of comprehensiveness and reliability. In over

73 studies that together included 53,424 military members, some

research shows that there is gradual improvement in mental health at

high altitudes, such as mountain tops; other researchers found that depressive symptoms can worsen.

These research studies demonstrate how difficult it is to assess and

treat the mental illness that occurs in the army and how there are

inconsistent results. Studies of the military population focus on the

men of the military and exclude women, even though the number of women

that are joining the military has increased in the last two decades.

Chinese researchers try to provide solutions that are

preventative and reactive, such as implementing early mental health

training,

or mental health assessments to help service members understand their

mental health state, and how to combat these feelings themselves.

Researchers also suggest to improve the mental health of the military

members, programs should include psychoeducation, psychological

training, and attention to physical health to employ timely

intervention.

Implementation

In 2006, the People's Republic Minister for National Defense began

mental health vetting at the beginning of the military recruitment

process.

A Chinese military study consisting of 2500 male military personnel

found that some members are more predisposed to mental illness. The

study measured levels of anxious behaviors, symptoms of depression,

sensitivity to traumatic events, resilience and emotional intelligence

of existing personnel to aid the screening of new recruits.

Similar research has been conducted into the external factors that

impact a person's mental fortitude, including single-child status, urban

or rural environment, and education level. Subsequently, the government has incorporated mental illness coping techniques into their training manual. In 2013 leak by the Tibetan Center for Human Rights of a small portion of the People's Liberation Army

training manual from 2008, specifically concerned how military

personnel could combat PTSD and depression while on peacekeeping

missions in Tibet. The manual suggested that soldiers should:

“...close [their] eyes and imagine zooming in on the scene like a camera [when experiencing PTSD]. It may feel uncomfortable. Then zoom all the way out until you cannot see anything. Then tell yourself the flashback is gone.”

In

2012, the government specifically addressed military mental health in a

legal document for the first time. In article 84 of the Mental Health

Law of the People's Republic of China, it stated, “The State Council

and the Central Military Committee will formulate regulations based on

this law to manage mental health work in the military."

Besides screening, assessments and an excerpt of the manual, not

much is known about the services that are provided to active military

members and veterans. Analysis of more than 45 different studies,

moreover, has deemed that the level of anxiety in current and

ex-military personnel has increased despite efforts of the People's

Republic due to economic conditions, lack of social connects and the

feeling of a threat to military livelihood.

This growing anxiety manifested in both 2016 and 2018, as Chinese

veterans demonstrated their satisfaction with the system via protests

across China.

In both instances, veterans advocated for an increased focus on

post-service benefits, resources to aid in post-service jobs, and

justice for those who were treated poorly by the government.

As a way to combat the dissatisfaction of veterans and alleviate

growing tension, the government established the Ministry of Veteran

Affairs in 2018. At the same time, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, promised to enact laws that protect the welfare of veterans.