Economic history of France

since its late-18th century Revolution was tied to three major events

and trends: the Napoleonic Era, the competition with Britain and its

other neighbors in regards to 'industrialization', and the 'total wars'

of the late-19th and early 20th centuries.

Medieval France

The collapse of the Roman Empire

unlinked the French economy from Europe. Town and city life and trade

declined and society became based on the self-sufficient manor. What limited international trade existed in the Merovingian age — primarily in luxury goods such as silk, papyrus, and silver — was carried out by foreign merchants such as the Radhanites.

Agricultural output began to increase in the Carolingian

age as a result of the arrival of new crops, improvements in

agricultural production, and good weather conditions. However, this did

not lead to the revival of urban life; in fact, urban activity further

declined in the Carolingian era as a result of civil war, Arab raids,

and Viking invasions. The Pirenne hypotheses

posits that at this disruption brought an end to long-distance trade,

without which civilization retreated to purely agricultural settlements,

and isolated military, church, and royal centers. When trade revived

these centers became the nucleus of new towns and cities around which

suburbs of merchants and artisans grew.

The High Middle Ages

saw a continuation of the agricultural boom of the Carolingian age. In

addition, urban life grew during this period; towns such as Paris expanded dramatically.

The 13 decades from 1335 to 1450 spawned a series of economic

catastrophes, with bad harvests, famines, plagues, and wars that

overwhelmed four generations of Frenchmen. The population had expanded,

making the food supply more precarious. The bubonic plague ("Black Death")

hit Western Europe in 1347, killing a third of the population, and it

was echoed by several smaller plagues at 15-year intervals. The French

and English armies during the Hundred Years War

marched back and forth across the land; they ransacked and burned

towns, drained the food supply, disrupted agriculture and trade, and

left disease and famine in their wake. Royal authority weakened, as

local nobles became strongmen fighting their neighbors for control of

the local region. France's population plunged from 17 million, down to

12 million in 130 years. Finally, starting in the 1450s, a long cycle of

recuperation began.

Early Modern France

(Figures cited in the following section are given in livre tournois,

the standard "money of account" used in the period. Comparisons with

modern figures are extremely difficult; food items were comparatively

cheap, but luxury goods and fabrics were very expensive. In the 15th

century, an artisan could earn perhaps 30 livres a year; a great noble

could have land revenues from 6000 to 30,000 livres or more. A late seventeenth-century unskilled worker in Paris earned around 250 livres a year, while a revenue of 4000 livres a year maintained a relatively successful writer in modest comfort.

At the end of the 18th century, a well-off family could earn 100,000

livres by the end of the year, although the most prestigious families

could gain twice or three times that much, while, for provincial

nobility, yearly earnings of 10,000 livres permitted a minimum of

provincial luxury).

Renaissance

The economy of Renaissance

France was, for the first half-century, marked by dynamic demographic

growth and by developments in agriculture and industry. Until 1795,

France was the most populated country in Europe and the third most

populous country in the world, behind only China and India.

With an estimated population of 17 million in 1400, 20 million in the

17th century, and 28 million in 1789, its population exceeded even Russia and was twice the size of Britain

and Holland. In France, the Renaissance was marked by a massive

increase in urban populations, although on the whole, France remained a

profoundly rural country, with less than 10% of the population located

in urban areas. Paris was one of the most populated cities in Europe, with an estimated population of 650,000 by the end of the 18th century.

Agricultural production of a variety of food items expanded: olive oil, wine, cider, woad (Fr. "pastel", a source of blue dye), and saffron. The South grew artichokes, melons, romaine lettuce, eggplant, salsifys, celery, fennel, parsley, and alfalfa. After 1500 New World crops appeared such as beans, corn (maize), squash, tomatoes, potatoes, and bell peppers.

Production techniques remained attached to medieval traditions and

produced low yields. With the rapidly expanding population, additional

land suitable for farming became scarce. The situation was made worse by

repeated disastrous harvests in the 1550s.

Industrial developments greatly affected printing (introduced in

1470 in Paris, 1473 in Lyon) and metallurgy. The introduction of the

high-temperature forge

in northeast France and an increase in mineral mining were important

developments, although it was still necessary for France to import many

metals, including (copper, bronze, tin, and lead).

Mines and glasswork benefited greatly from royal tax exemptions for a

period of about twenty years. Silk production (introduced in Tours in 1470 and in Lyon

in 1536) enabled the French to join a thriving market, but French

products remained of lesser quality than Italian silks. Wool production

was widespread, as was the production of linen and of hemp (both major export products).

After Paris, Rouen was the second largest city in France (70,000 inhabitants in 1550), in large part because of its port. Marseille (French since 1481) was France's second major port: it benefited greatly from France's trading agreements signed in 1536 with Suleiman the Magnificent. To increase maritime activity, Francis I founded the port city of Le Havre in 1517. Other significant ports included Toulon, Saint Malo and La Rochelle.

Lyon

was the center of France's banking and international trade markets.

Market fairs occurred four times a year and facilitated the exportation

of French goods, such as cloth and fabrics, and importation of Italian,

German, Dutch, English goods. It also allowed the importation of exotic

goods such as silks, alum, glass, wools, spices, dyes. Lyon also contained houses of most of Europe's banking families, including Fugger and Medici. Regional markets and trade routes

linked Lyon, Paris, and Rouen to the rest of the country. Under

Francis I and Henry II, the relationships between French imports and the

exports to England and to Spain were in France's favor. Trade was

roughly balanced with the Netherlands, but France continually ran a

large trade deficit

with Italy due to the latter's silks and exotic goods. In subsequent

decades, English, Dutch and Flemish maritime activity would create

competition with French trade, which would eventually displace the major

markets to the northwest, leading to the decline of Lyon.

Although France, being initially more interested in the Italian

wars, arrived late to the exploration and colonization of the Americas,

private initiative and piracy brought Bretons, Normans and Basques early to American waters. Starting in 1524, Francis I began to sponsor exploration of the New World. Significant explorers sailing under the French flag included Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier. Later, Henry II sponsored the explorations of Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon who established a largely Calvinist colony in Rio de Janeiro, 1555-1560. Later, René Goulaine de Laudonnière and Jean Ribault established a Protestant colony in Florida (1562–1565).

By the middle of the 16th century, France's demographic growth,

its increased demand for consumer goods, and its rapid influx of gold

and silver from Africa and the Americas led to inflation (grain became

five times as expensive from 1520 to 1600), and wage stagnation.

Although many land-owning peasants and enterprising merchants had been

able to grow rich during the boom, the standard of living fell greatly

for rural peasants, who were forced to deal with bad harvests at the

same time. This led to reduced purchasing power and a decline in manufacturing. The monetary crisis led France to abandon (in 1577) the livre as its money of account, in favor of the écu in circulation, and banning most foreign currencies.

Meanwhile, France's military ventures in Italy and (later)

disastrous civil wars demanded huge sums of cash, which were raised with

through the taille

and other taxes. The taille, which was levied mainly on the peasantry,

increased from 2.5 million livres in 1515 to 6 million after 1551, and

by 1589 the taille had reached a record 21 million livres. Financial

crises hit the royal household repeatedly, and so in 1523, Francis I

established a government bond system in Paris, the "rentes sure l'Hôtel

de Ville".

The French Wars of Religion

were concurrent with crop failures and epidemics. The belligerents

also practiced massive "torched earth" strategies to rob their enemies

of foodstuffs. Brigands and leagues of self-defense flourished;

transport of goods ceased; villagers fled to the woods and abandoned

their lands; towns were set on fire. The south was particularly

affected: Auvergne, Lyon, Burgundy, Languedoc—agricultural

production in those areas fell roughly 40%. The great banking houses

left Lyon: from 75 Italian houses in 1568, there remained only 21 in

1597.

Rural society

In the 17th century rich peasants who had ties to the market economy

provided much of the capital investment necessary for agricultural

growth, and frequently moved from village to village (or town).

Geographic mobility, directly tied to the market and the need for

investment capital, was the main path to social mobility. The "stable"

core of French society, town guildspeople and village laborers, included

cases of staggering social and geographic continuity, but even this

core required regular renewal. Accepting the existence of these two

societies, the constant tension between them, and extensive geographic

and social mobility tied to a market economy holds the key to a clearer

understanding of the evolution of the social structure, economy, and

even political system of early modern France. Collins (1991) argues that

the Annales School

paradigm underestimated the role of the market economy; failed to

explain the nature of capital investment in the rural economy, and

grossly exaggerated social stability.

Seventeenth century

After 1597, the French economic situation improved and agricultural production was aided by milder weather. Henry IV, with his minister Maximilien de Béthune, Duc de Sully, adopted monetary reforms. These included better coinage, a return to the livre tournois

as account money, reduction of the debt, which was 200 million livres

in 1596, and a reduction of the tax burden on peasants. Henry IV

attacked abuses, embarked on a comprehensive administrative reform,

increased charges for official offices, the "paulette",

repurchased alienated royal lands, improved roads and the funded the

construction of canals, and planted the seed of a state-supervised mercantile philosophy. Under Henry IV, agricultural reforms, largely started by Olivier de Serres were instituted. These agricultural and economic reforms, and mercantilism would also be the policies of Louis XIII's minister Cardinal Richelieu. In an effort to counteract foreign imports and exploration, Richelieu sought alliances with Morocco and Persia, and encouraged exploration of New France, the Antilles, Sénégal, Gambia and Madagascar, though only the first two were immediate successes. These reforms would establish the groundwork for the Louis XIV's policies.

Louis XIV's glory was irrevocably linked to two great projects, military conquest and the building of Versailles—both

of which required enormous sums of money. To finance these projects,

Louis created several additional tax systems, including the "capitation"

(begun in 1695) which taxed every person including nobles and the

clergy, though exemption could be bought for a large one-time sum, and

the "dixième" (1710–1717, restarted in 1733), which was a true tax on

income and on property value and was meant to support the military.

Louis XIV's minister of finances, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, started a mercantile system which used protectionism

and state-sponsored manufacturing to promote the production of luxury

goods over the rest of the economy. The state established new

industries (the royal tapestry works at Beauvais, French quarries for marble), took over established industries (the Gobelins tapestry works), protected inventors, invited workmen from foreign countries (Venetian glass and Flemish

cloth manufacturing), and prohibited French workmen from emigrating. To

maintain the character of French goods in foreign markets, Colbert had

the quality and measure of each article fixed by law, and severely

punished breaches of the regulations. This massive investment in (and

preoccupation with) luxury goods and court life (fashion, decoration,

cuisine, urban improvements, etc.), and the mediatization (through such

gazettes as the Mercure galant) of these products, elevated France to a role of arbiter of European taste.

Unable to abolish the duties on the passage of goods from

province to province, Colbert did what he could to induce the provinces

to equalize them. His régime improved roads and canals. To encourage

companies like the important French East India Company (founded in 1664), Colbert granted special privileges to trade with the Levant, Senegal, Guinea and other places, for the importing of coffee, cotton, dyewoods, fur, pepper, and sugar,

but none of these ventures proved successful. Colbert achieved a

lasting legacy in his establishment of the French royal navy; he

reconstructed the works and arsenal of Toulon, founded the port and arsenal of Rochefort, and the naval schools of Rochefort, Dieppe and Saint-Malo. He fortified, with some assistance from Vauban, many ports including those of Calais, Dunkirk, Brest and Le Havre.

Colbert's economic policies were a key element in Louis XIV's

creation of a centralized and fortified state and in the promotion of

government glory, including the construction they had many economic

failures: they were overly restrictive on workers, they discouraged

inventiveness, and had to be supported by unreasonably high tariffs.

The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 created additional economic problems: of the more than 200,000 Huguenot refugees who fled France for Prussia, Switzerland, England, Ireland, United Provinces, Denmark, South Africa and eventually America,

many were highly educated skilled artisans and business-owners who took

their skills, businesses, and occasionally even their Catholic workers,

with them. Both the expansion of French as a European lingua franca in the 18th century, and the modernization of the Prussian army have been credited to the Huguenots.

The wars and the weather at the end of the century brought the

economy to the brink. Conditions in rural areas were grim from the

1680s to 1720s. To increase tax revenues, the taille

was augmented, as too were the prices of official posts in the

administration and judicial system. With the borders guarded due to

war, international trade was severely hindered. The economic plight of

the vast majority of the French population — predominantly simple

farmers — was extremely precarious, and the Little Ice Age resulted in further crop failures. Bad harvests caused starvation—killing s tenth of the people in 1693-94.

Unwilling to sell or transport their much-needed grain to the army,

many peasants rebelled or attacked grain convoys, but they were

repressed by the state. Meanwhile, wealthy families with stocks of

grains survived relatively unscathed; in 1689 and again in 1709, in a

gesture of solidarity with his suffering people, Louis XIV had his royal

dinnerware and other objects of gold and silver melted down.

Eighteenth century

France

was large and rich and experienced a slow economic and demographic

recovery in the first decades following the death of Louis XIV in 1715.

Birth rates were high and the infant mortality rate was in steady

decline. The overall mortality rate in France fell from an average of

400 deaths per 10,000 people in 1750, to 328 in 1790, and 298 per 10,000

in 1800.

Monetary confidence was briefly eroded by the disastrous paper money "System" introduced by John Law from 1716 to 1720. Law, as Controller General of Finances, established France's first central bank, the Banque Royale, initially founded as a private entity by Law in 1716 and nationalized in 1718.

The bank was entrusted with paying down the enormous debt accumulated

through Louis XIV's wars and stimulating the moribund French economy.

Initially a great success, the bank's pursuit of French monopolies led

it to land speculation in Louisiana through the Mississippi Company, forming an economic bubble in the process that eventually burst in 1720.

The collapse of the Banque Royale in the crisis and the paper currency

which it issued left a deep suspicion of the idea of a central bank; it

was not until 80 years later that Napoleon established the Bank of

France. In 1726, under Louis XV's minister Cardinal Fleury,

a system of monetary stability was put in place, leading to a strict

conversion rate between gold and silver, and set values for the coins in

circulation in France.

The amount of gold in circulation in the kingdom rose from 731 million

livres in 1715 to 2 billion in 1788 as economic activity accelerated.

A view of the port of Bordeaux in 1759

The international commercial centers of the country were based in Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, and Bordeaux. Nantes and Bordeaux saw phenomenal growth due to an increase of trade with Spain and Portugal. Trade between France and her Caribbean colonies (Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Martinique) grew ten-fold between 1715 and 1789, with Saint Domingue the single richest territory in the world by 1789.

Much of the lucrative imports from the Caribbean were re-exported to

other European countries. By the late 1780s, 87% of the sugar, 95% of

the coffee, and 76% of the indigo imported to Bordeaux from the

Caribbean was being re-exported. Cádiz was the commercial hub for export of French printed fabrics to India, the Americas and the Antilles (coffee, sugar, tobacco, American cotton), and Africa (the slave trade), centered in Nantes. The value of this export activity amounted to nearly 25% of the French national income by 1789.

Industry continued to expand, averaging 2% growth per year from

the 1740s onwards and accelerating in the last decades before the

Revolution.

The most dynamic industries of the period were mines, metallurgy, and

textiles (in particularly printed fabrics, such as those made by Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf). The advancements in these areas were often due to British inventors. For example, it was John Kay's invention of the flying shuttle that revolutionized the textile industry, and it was James Watt's steam engine

that changed the industry as the French had known it. Capital remained

difficult to raise for commercial ventures, however, and the state

remained highly mercantilistic, protectionist, and interventionist

in the domestic economy, often setting requirements for production

quality and industrial standards, and limiting industries to certain

cities.

In 1749, a new tax, modeled on the "dixième" and called the

"vingtième" (or "one-twentieth"), was enacted to reduce the royal

deficit. This tax continued throughout the ancien régime. It was based

solely on revenues, requiring 5% of net earnings from land, property,

commerce, industry and from official offices, and was meant to touch all

citizens regardless of status. However, the clergy, the regions with

"pays d'état" and the parlements protested; the clergy won exemption,

the "pays d'état" won reduced rates, and the parlements halted new

income statements, effectively making the "vingtième" a far less

efficient tax than it was designed to be. The financial needs of the Seven Years' War

led to a second (1756–1780), and then a third (1760–1763), "vingtième"

being created. In 1754, the "vingtième" produced 11.7 million livres.

Improvements in communication, like an expanding network of roads and canals, and the diligence

stagecoach services which by the 1780s had sharply reduced travel times

between Paris and the provincial cities, went a long way towards

expanding trade within France. However, most French markets were

overwhelmingly local in character (by 1789 only 30% of agricultural

produce was being sold in a place other than where it was produced).

Price discrepancies between regions and heavy internal customs barriers,

which made for exorbitant transportation costs, meant that a unified

national market like that of Britain was still far off. On the eve of the Revolution, a shipment of goods travelling from Lorraine to the Mediterranean coast would have been stopped 21 times and incurred 34 different duties.

Agriculture

Starting

in the late 1730s and early 1740s, and continuing for the next 30

years, France's population and economy underwent expansion. Rising

prices, particularly for agricultural products, were extremely

profitable for large landholders. Artisans and tenant farmers also saw

wage increases but on the whole, they benefited less from the growing

economy. The ownership share of the peasantry remained largely the same

as it had in the previous century, with around 1/3 of arable land in the

hands of peasant smallholders in 1789.

A newer trend was the amount of land which came into the hands of

bourgeois owners during the 18th century: fully 1/3 of the arable land

in France by 1789.

The stability of land ownership made it a very attractive investment

for the bourgeois, as did the social prestige which it brought.

Pivotal developments in agriculture such as modern techniques of crop rotation

and the use of fertilizers, which were modeled on successes in Britain

and Italy, began to be introduced in parts of France. It would, however,

take generations for these reforms to spread throughout all of France.

In northern France the three-field system of crop rotation still

prevailed, and in the south the two-field system. Under such methods, farmers left either one third or half of their arable land vacant as fallow

every year to restore fertility in cycles. This was both a considerable

waste of land at any one time which might otherwise have been

cultivated, and an inferior way of restoring fertility compared to

planting restorative fodder crops.

Farming of recent New World crops, including maize

(corn) and potatoes, continued to expand and provided an important

supplement to the diet. However, the spread of these crops was

geographically limited (potatoes to Alsace and Lorraine, and maize in the more temperate south of France), with the bulk of the population over-reliant on wheat for subsistence.

From the late 1760's onwards harsher weather caused consistently poor

wheat harvests (there were only three between 1770 and 1789 which were

deemed sufficient).

The hardship bad harvests caused mainly affected the small

proprietors and peasants who constituted the bulk of French farmers;

large land owners continued to prosper from rising land prices and

strong demand. The more serious recurrent threat was that of bread

shortages and steep price rises, which could cause mass disruption and

rioting. The average wage earner in France, during periods of abundance,

might spend as much as 70% of his income on bread alone. During

shortages, when prices could rise by as much as 100%, the threat of

destitution increased dramatically for French families.

The French government experimented unsuccessfully with regulating the

grain market, lifting price controls in the late 1760s, re-imposing them

in the early 1770s, then lifting them again in 1775. Abandoning price

controls in 1775, after a bad harvest the previous year, caused grain

prices to skyrocket by 50% in Paris; the rioting which erupted as a

result (known as the Flour War), engulfed much of northeastern France and had to be put down with force.

Slave trade

The slaving interest was based in Nantes, La Rochelle, Bordeaux, and

Le Havre during the years 1763 to 1792. The 'négriers' were merchants

who specialized in funding and directing cargoes of black captives to

the Caribbean colonies, which had high death rates and needed a

continuous fresh supply. The négriers intermarried with each other's

families; most were Protestants. Their derogatory and patronizing

approach toward blacks immunized them from moral criticism. They

strongly opposed to the application of the Declaration of Rights of Man

to blacks. While they ridiculed the slaves as dirty and savage, they

often took a black mistress. The French government paid a bounty on each

captive sold to the colonies, which made the business profitable and

patriotic. They vigorously defended their business against the abolition

movement of 1789.

1770-1789

The

agricultural and climatic problems of the 1770s and 1780s led to an

important increase in poverty: in some cities in the north, historians

have estimated the poor as reaching upwards of 20% of the urban

population. Displacement and criminality, mainly theft, also increased,

and the growth of groups of mendicants and bandits became a problem.

Overall about one third of the French population lived in poverty,

approximately 8 million people. This could rise by several million

during bad harvests and the resulting economic crises.

Although nobles, bourgeoisie, and wealthy landholders saw their

revenues affected by the depression, the hardest-hit in this period were

the working class and the peasants. While their tax burden to the state

had generally decreased in this period, feudal and seigneurial dues had

increased.

Louis XVI distributing money to the poor of Versailles, during the brutal winter of 1788

In these last decades of the century, French industries continued to

develop. Mechanization was introduced, factories were created, and

monopolies became more common. However, this growth was complicated by

competition from England in the textiles and cotton industries. The

competitive disadvantage of French manufactures was sorely demonstrated

after the 1786 Anglo-French commercial treaty opened the French market

to British goods beginning in mid-1787.

The cheaper and superior quality British products undercut domestic

manufactures, and contributed to the severe industrial depression

underway in France by 1788.

The depression was worsened by a catastrophic harvest failure during

the summer of 1788, which reverberated across the economy. As peasants

and wage earners were forced to spend higher proportions of their income

on bread, demand for manufactured goods evaporated.

The American War of Independence

had led to a reduction of trade (cotton and slaves), but by the 1780s

Franco-American trade was stronger than before. Similarly, the Antilles represented the major source for European sugar and coffee, and it was a huge importer of slaves through Nantes. Paris became France's center of international banking and stock trades, in these last decades (like Amsterdam and London), and the Caisse d'Escompte was founded in 1776. Paper money was re-introduced, denominated in livres; these were issued until 1793.

The later years of Louis XV's reign saw some economic setbacks. While the Seven Years' War,

1756–1763, led to an increase in the royal debt and the loss of nearly

all of France's North American possessions, it was not until 1775 that

the French economy began truly to enter a state of crisis. An extended

reduction in agricultural prices over the previous twelve years, with

dramatic crashes in 1777 and 1786, and further complicated by climatic

events such as the disastrous winters of 1785-1789 contributed to the

problem. With the government deeply in debt, King Louis XVI was forced to permit the radical reforms of Turgot and Malesherbes. However, the nobles' disaffection led to Turgot's dismissal and Malesherbes' resignation 1776. Jacques Necker replaced them. Louis supported the American Revolution in 1778, but the Treaty of Paris (1783)

yielded the French little, excepting an addition to the country's

enormous debt. The government was forced to increase taxes, including

the "vingtième." Necker had resigned in 1781, to be replaced

temporarily by Calonne and Brienne, but he was restored to power in 1788.

1789–1914

French economic history since its late-18th century Revolution was

tied to three major events and trends: the Napoleonic Era, the

competition with Britain and its other neighbors in regards to

'industrialization', and the 'total wars' of the late-19th and early

20th centuries. Quantitative analysis of output data shows the French

per capita growth rates were slightly smaller than Britain. However the

British population tripled in size, while France grew by only third—so

the overall British economy grew much faster. François Crouzet has

succinctly summarized the ups and downs of French per capita economic

growth in 1815-1913 as follows:

- 1815-1840: irregular, but sometimes fast growth

- 1840-1860: fast growth;

- 1860-1882: slowing down;

- 1882-1896: stagnation;

- 1896-1913: fast growth

For the 1870-1913 era, Angus Maddison gives growth rates for 12

Western advanced countries—10 in Europe plus the United States and

Canada.

In terms of per capita growth, France was about average. However

again its population growth was very slow, so as far as the growth rate

in total size of the economy France was in next to the last place, just

ahead of Italy. The 12 countries averaged 2.7% per year in total

output, but France only averaged 1.6%. Crouzet argues that the:

- average size of industrial undertakings was smaller in France than in other advanced countries; that machinery was generally less up to date, productivity lower, costs higher. The domestic system and handicraft production long persisted, while big modern factories were for long exceptional. Large lumps of the Ancien Régime economy survived...On the whole, the qualitative lag between the British and French economy...persisted during the whole period under consideration, and later on a similar lag developed between France and some other countries—Belgium, Germany, the United States. France did not succeed in catching up with Britain, but was overtaken by several of her rivals.

French Revolution

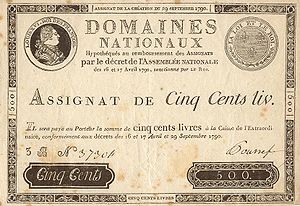

Early Assignat of 29 Sept, 1790: 500 livres

The value of Assignats (1789-1796)

"The French Revolution abolished many of the constraints on the

economy that had emerged during the old regime. It abolished the guild

system as a worthless remnant of feudalism."

It also abolished the highly inefficient system of tax farming,

whereby private individuals would collect taxes for a hefty fee. The

government seized the foundations that had been set up (starting in the

13th century) to provide an annual stream of revenue for hospitals, poor

relief, and education. The state sold the lands but typically local

authorities did not replace the funding and so most of the nation's

charitable and school systems were massively disrupted.

The economy did poorly in 1790-96 as industrial and agricultural

output dropped, foreign trade plunged, and prices soared. The

government decided not to repudiate the old debts. Instead, it issued

more and more paper money (called an "assignat") that supposedly were

grounded seized lands. The result was escalating inflation. The

government imposed price controls and persecuted speculators and traders

in the black market. People increasingly refused to pay taxes as the

annual government deficit increased from 10% of gross national product

in 1789 to 64% in 1793. By 1795, after the bad harvest of 1794 and the

removal of price controls, inflation had reached a level of 3500%.

Throughout January and February 1795, the Seine River(the

main source of import and export of goods at the time) froze, making it

impossible to transport anything through there, such as food, luxury

goods, and materials that factories depended on in order to keep

running.

Many factories and workshops were forced to close because they had no

way to operate, this led to an increased amount of unemployment. With

unemployment soaring, many of the poor (most of the population) were

forced to sell their belongings.

On the other hand, the very few who were wealthy, could afford anything

they needed. "The markets were well stocked, but the food could only be

bought at excessive prices".

The value of the assignats "had plunged from 31 percent of that of the silver currency in July 1794 to 8 percent in March 1795"

The main cause of assignat depreciation was over-issuance by successive

revolutionary governments, who turned to printing more and more paper

notes to fund escalating expenditure, especially after the advent of war

in 1792. Some 45 billion livres worth of paper had been printed by

1797, which collectively were worth less than one seventh that amount

based on 1790 prices.

The depreciation of the assignat not only caused spiraling inflation,

but had knock-on effects across the entire economy. Because assignats

were legal tender, they could be used to service debt repayments at face

value, although their real value stood at only a fraction of this. The

losses that lenders suffered as a result led them to tighten credit and

raise interest rates. Likewise the real value of national lands, which

the assignats were pegged to, sank to only 25% of their face value. The assignats

were withdrawn in 1796 but the replacements also fueled inflation. The

inflation was finally ended by Napoleon in 1803 with the gold franc as

the new currency.

The diminution of the economic power of the nobility and the

clergy also had serious disruptive effects on the French economy. With

the closure of monasteries, chapters, and cathedrals in towns like Tours, Avignon or Bayeux,

thousands were deprived of their livelihoods as servants, artisans, or

tradesmen. Likewise, the exodus of nobles devastated the luxury trades

and led to still greater hardship for servants, as well as industries

and supply networks dependent on aristocratic consumption. For those

nobles who remained in France, the heated anti-aristocratic social

environment dictated more modest patterns of dress and consumption,

while the spiraling inflation of the assignats dramatically reduced

their buying power. The plunging market for silk, for example, meant

that output in the silk capital of Lyons fell by half between 1789–99, contributing to a loss of almost one-third of Lyons' pre-revolutionary population.

In the cities entrepreneurship on a small scale flourished, as

restrictive monopolies, privileges, barriers, rules, taxes, and guilds

gave way. However, the British blockade which began in 1793 severely

damaged overseas trade. The wartime exigencies enacted that year by the National Convention

worsened the situation by banning the export of essential goods and

embargoing neutral shipping from entering French ports. Although these

restrictions were lifted in 1794, the British had managed to usurp

transatlantic shipping lanes in the meantime, further reducing markets

for French goods. By 1796, foreign trade accounted for just 9% of the

French economy, compared to 25% in 1789.

Agriculture

Agriculture

was transformed by the Revolution. It abolished tithes owed to local

churches as well as feudal dues owed to local landlords. The result

hurt the tenants, who paid both higher rents and higher taxes.

It nationalized all church lands, as well as lands belonging to

royalist enemies who went into exile. The Government in Paris planned to

use these seized lands to finance expenditure by issuing assignats.

With the breakup of large estates controlled by the Church and the

nobility and worked by hired hands, rural France became permanently a

land of small independent farms. The rural proletariat and nobility both

gave way to the commercial farmer. Cobban says the revolution "bequeathed to the nation "a ruling class of landowners." Most of these new landowners were bourgeois in origin, as the economic uncertainties of the 1790s and the abolition of venal office made land ownership an attractive and safe investment.

However, the recruitment needs of the wartime French Republic

between 1792 and 1802 led to shortages of agricultural workers. Farmers

were also subject to requisition of their livestock by passing armies;

the consequent losses of manure negatively impacted the fertility and

productivity of the land.

Overall the Revolution did not greatly change the French business

system and probably helped freeze in place the horizons of the small

business owner. The typical businessman owned a small store, mill or

shop, with family help and a few paid employees; large-scale industry

was less common than in other industrializing nations.

Napoleon and Bourbon reaction: 1799-1830

Napoleon

after 1799 paid for his expensive wars by multiple means, starting with

the modernization of the rickety financial system.

He conscripted soldiers at low wages, raised taxes, placed large-scale

loans, sold lands formerly owned by the Catholic Church, sold Louisiana

to the United States, plundered conquered areas and seized food

supplies, and did requisitions on countries he controlled, such as

Italy.

The constant "war-footing" of the Napoleonic Era,

1795–1815, stimulated production at the cost of investment and growth.

Production of armaments and other military supplies, fortifications,

and the general channeling of the society toward the establishment and

maintenance of massed armies, temporarily increased economic activity

after several years of revolution. The rampant inflation of the

Revolutionary era was halted by not printing the new currency quite as

fast. The maritime Continental Blockade, implemented by Napoleon's opponents and very effectively enforced by the Royal Navy,

gradually cut into any economic arena in which the French economy was

not self-sufficient. 1815 saw the final defeat of the French forces and

the collapse of its war footing.

This gave rise to a relatively peaceful period in the whole of Europe

until 1914, during which important institutional reforms such as the

introduction of a highly rationalized legal system could be implemented.

Napoleon's impact on the French economy was of modest importance

in the long run. He did sweep away the old guilds and monopolies and

trade restrictions. He introduced the metric system and fostered the

study of engineering. Most important he opened up French finance by the

creation of the indispensable Bank of France.

However, entrepreneurs had little opportunity to take advantage of

these reforms. Napoleon provided a protected continental market by

systematic exclusion of all imports from Britain. This had the effect

of encouraging innovation in Britain, where the Industrial Revolution

was well underway, and diverting the need for innovation in France.

What innovation took place focused on armaments for the army, and was of

little value in peacetime. In France the business crisis in 1810-1812

undermined what successes entrepreneurs had achieved.

With the restoration of the Bourbons in 1814, the reactionary

aristocracy with its disdain for entrepreneurship return to power.

British goods flooded the market, and France responded with high tariffs

and protectionism, to protect its established businesses especially

handcrafts and small-scale manufacturing such as textiles. The tariff

on iron goods reached 120%.

Agriculture had never needed protection but now demanded it from the lower prices of imported foodstuffs, such as Russian grain.

French winegrowers strongly supported the tariff – their wines did not

need it, but they insisted on a high tariff on the import of tea. One

agrarian deputy explained: "Tea breaks down our national character by

converting those who use it often into cold and stuffy Nordic types,

while wine arouses in the soul that gentle gaiety that gives Frenchmen

their amiable and witty national character." The French government falsified the statistics to claim that exports

and imports were growing – actually there was stagnation and the

economic crisis of 1826-29 disillusioned the business community and

readied them to support the revolution in 1830.

Banking and finance

Perhaps the only successful and innovative economic sector was banking. Paris emerged as an international center of finance in the mid-19th century second only to London.

It had a strong national bank and numerous aggressive private banks

that financed projects all across Europe and the expanding French

Empire. Napoleon III had the goal of overtaking London to make Paris the

premier financial center of the world, but the war in 1870 reduced the

range of Parisian financial influence. One key development was setting up one of the main branches of the Rothschild family.

In 1812, James Mayer Rothschild arrived in Paris from Frankfurt, and set up the bank "De Rothschild Frères". This bank funded Napoleon's return from Elba and became one of the leading banks in European finance. The Rothschild banking family of France funded France's major wars and colonial expansion. The Banque de France, founded in 1796 helped resolve the financial crisis of 1848 and emerged as a powerful central bank. The Comptoir National d'Escompte de Paris

(CNEP) was established during the financial crisis and the Republican

revolution of 1848. Its innovations included both private and public

sources in funding large projects and the creation of a network of local

offices to reach a much larger pool of depositors.

The Péreire brothers founded the Crédit Mobilier.

It became a powerful and dynamic funding agency for major projects in

France, Europe and the world at large. It specialized in mining

developments; it funded other banks including the Imperial Ottoman Bank

and the Austrian Mortgage Bank; it funded railway construction.

It also funded insurance companies and building contractors. The bank

had large investments in a transatlantic steamship line, urban gas lighting, a newspaper and the Paris Paris Métro public transit system. Other major banks included the Société Générale, and in the provinces the Crédit Lyonnais.

After its defeat in 1871, France had to pay enormous reparations to

Germany, with the German army continuing its occupation until the debt

was paid. The 5 billion francs amounted to a fourth of France's GNP –

and one-third of Germany's and was nearly double the usual annual

exports of France. Observers thought the indemnity was unpayable and

was designed to weaken France and justify long years of military

occupation. However France paid it off in less than three years. The

payments, in gold, acted as a powerful stimulus that dramatically

increased the volume of French exports, and on the whole, produced

positive economic benefits for France.

The Paris Bourse

or stock exchange emerged as a key market for investors to buy and sell

securities. It was primarily a forward market, and it pioneered in

creating a mutual guarantee fund so that failures of major brokers would

not escalate into a devastating financial crisis. Speculators in the

1880s who disliked the control of the Bourse used a less regulated

alternative the Coulisse. However, it collapsed in the face of the

simultaneous failure of a number of its brokers in 1895–1896. The Bourse

secured legislation that guaranteed its monopoly, increased control of

the curb market, and reduced the risk of another financial panic.

Industrialization

France

in 1815 was overwhelmingly a land of peasant farms, with some

handicraft industry. Paris, and the other much smaller urban centers had

little industry. On the onset of the nineteenth century, GDP per capita

in France was lower than in Great Britain and the Netherlands. This was

probably due to higher transaction costs, which were mainly caused by

inefficient property rights and a transportation system geared more to

military needs than to economic growth.

Historians are reluctant to use the term "Industrial Revolution"

for France because the slow pace seems an exaggeration for France as a

whole.

The Industrial Revolution was well underway in Britain when the

Napoleonic wars ended, and soon spread to Belgium and, to a lesser

extent to northeastern France. The remainder remained little changed.

The growth regions developed industry, based largely on textiles, as

well as some mining. The pace of industrialization was far below

Britain, Germany, the United States and Japan. The persecution of the

Protestant Huguenots

after 1685 led to a large-scale flight of entrepreneurial and

mechanical talents that proved hard to replace. Instead French business

practices were characterized by tightly held family firms, which

emphasized traditionalism and paternalism. These characteristics

supported a strong banking system, and made Paris a world center for

luxury craftsmanship, but it slowed the building of large factories and

giant corporations. Napoleon had promoted engineering education, and it

paid off in the availability of well-trained graduates who developed the

transportation system, especially the railways after 1840.

Retailing

Au Bon Marché

|

Paris became world-famous for making consumerism a social priority

and economic force, especially through its upscale arcades filled with

luxury shops and its grand department stores. These were "dream

machines" that set the world standard for consumption of fine products

by the upper classes as well as the rising middle class.

Paris took the lead internationally in elaborate department stores

reaching upscale consumers with luxury items and high quality goods

presented in a novel and highly seductive fashion. The Paris department

store had its roots in the magasin de nouveautés, or novelty store; the first, the Tapis Rouge, was created in 1784. They flourished in the early 19th century, with La Belle Jardiniere (1824), Aux Trois Quartiers (1829), and Le Petit Saint Thomas (1830). Balzac described their functioning in his novel César Birotteau.

In the 1840s, the new railroads brought wealthy consumers to Paris

from a wide region. Luxury stores grew in size, and featured plate glass

display windows, fixed prices and price tags, and advertising in

newspapers.

The entrepreneur Aristide Boucicaut in 1852 took Au Bon Marché,

a small shop in Paris, set fixed prices (with no need to negotiate with

clerks), and offered guarantees that allowed exchanges and refunds. He

invested heavily in advertising, and added a wide variety of

merchandise. Sales reached five million francs in 1860. In 1869 he moved

to larger premises; sales reached 72 million in 1877. The

multi-department enterprise occupied fifty thousand square meters with

1788 employees. Half the employees were women; unmarried women employees

lived in dormitories on the upper floors. The success inspired numerous

competitors all vying for upscale customers.

The French gloried in the national prestige brought by the great Parisian stores. The great writer Émile Zola (1840–1902) set his novel Au Bonheur des Dames

(1882–83) in the typical department store. Zola represented it as a

symbol of the new technology that was both improving society and

devouring it. The novel describes merchandising, management techniques,

marketing, and consumerism.

Other competitors moved downscale to reach much larger numbers of

shoppers. The Grands Magasins Dufayel featured inexpensive prices and

worked to teach workers how to shop in the new impersonal environment.

Its advertisements promised the opportunity to participate in the

newest, most fashionable consumerism at reasonable cost. The latest

technology was featured, such as cinemas and exhibits of inventions like

X-ray machines (used to fit shoes) and the gramophone.

Increasingly after 1870 the stores' work force became feminized,

opening up prestigious job opportunities for young women. Despite the

low pay and long hours they enjoyed the exciting complex interactions

with the newest and most fashionable merchandise and upscale customers.

By the 21st century, the grand Paris department stores had

difficulty surviving in the new economic world. In 2015, just four

remained; Au Bon Marché, now owned by the luxury goods firm LVMH; BHV; Galeries Lafayette and Printemps.

Railways

In France, railways became a national medium for the modernization of

backward regions, and a leading advocate of this approach was the

poet-politician Alphonse de Lamartine.

One writer hoped that railways might improve the lot of "populations

two or three centuries behind their fellows" and eliminate 'the savage

instincts born of isolation and misery."

Consequently, France built a centralized system that radiated from

Paris (plus lines that cut east to west in the south). This design was

intended to achieve political and cultural goals rather than maximize

efficiency. After some consolidation, six companies controlled

monopolies of their regions, subject to close control by the government

in terms of fares, finances, and even minute technical details. The

central government department of Ponts et Chaussées (bridges and roads,

or the Highways Department) brought in British engineers and workers,

handled much of the construction work, provided engineering expertise

and planning, land acquisition, and construction of permanent

infrastructure such as the track bed, bridges and tunnels. It also

subsidized militarily necessary lines along the German border, which was

considered necessary for the national defense.

Private operating companies provided management, hired labor,

laid the tracks, and built and operated stations. They purchased and

maintained the rolling stock—6,000 locomotives were in operation in

1880, which averaged 51,600 passengers a year or 21,200 tons of freight.

Much of the equipment was imported from Britain and therefore did not

stimulate machinery makers. Although starting the whole system at once

was politically expedient, it delayed completion, and forced even more

reliance on temporary exports brought in from Britain. Financing was

also a problem. The solution was a narrow base of funding through the Rothschilds

and the closed circles of the Bourse in Paris, so France did not

develop the same kind of national stock exchange that flourished in

London and New York. The system did help modernize the parts of rural

France it reached, but it did not help create local industrial centers. Critics such as Émile Zola complained that it never overcame the corruption of the political system, but rather contributed to it.

The railways helped the industrial revolution in France by

facilitating a national market for raw materials, wines, cheeses, and

imported manufactured products. Yet the goals set by the French for

their railway system were moralistic, political, and military rather

than economic. As a result, the freight trains were shorter and less

heavily loaded than those in such rapidly industrializing nations such

as Britain, Belgium or Germany. Other infrastructure needs in rural

France, such as better roads and canals, were neglected because of the

expense of the railways, so it seems likely that there were net negative

effects in areas not served by the trains.

Total War

In 1870 the relative decline in industrial strength, compared to Bismarck's Germany, proved decisive in the Franco-Prussian War.

The total defeat of France, in this conflict, was less a demonstration

of French weakness than it was of German militarism and industrial

strength. This contrasted with France's occupation of Germany during the

Napoleonic wars. By 1914, however, German armament and general

industrialization had out-distanced not only France but all of its

neighbors. Just before 1914, France was producing about one-sixth as

much coal as Germany, and a quarter as much steel.

Modernization of peasants

France

was a rural nation as late as 1940, but a major change took place after

railways started arriving in the 1850s–60s. In his seminal book Peasants Into Frenchmen (1976), historian Eugen Weber

traced the modernization of French villages and argued that rural

France went from backward and isolated to modern and possessing a sense

of French nationhood during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

He emphasized the roles of railroads, republican schools, and universal

military conscription. He based his findings on school records,

migration patterns, military service documents and economic trends.

Weber argued that until 1900 or so a sense of French nationhood was weak

in the provinces. Weber then looked at how the policies of the Third

Republic created a sense of French nationality in rural areas. The book

was widely praised, but was criticized by some, such as Ted W.

Margadant, who argued that a sense of Frenchness already existed in the

provinces before 1870.

French national policy was protectionist with regard to

agricultural products, to protect the very large agricultural

population, especially through the Méline tariff

of 1892. France maintained two forms of agriculture, a modern,

mechanized, capitalistic system in the Northeast, and in the rest of the

country a reliance on subsistence agriculture on very small farms with

low income levels.

Modernization of the subsistence sector began in the 1940s, and

resulted in a rapid depopulation of rural France, although protectionist

measures remained national policy.

1914–1944

The overall growth rate of the French economy shows a very strong

performance in the 1920s and again in the 1960s, with poor performances

in the 1910s, 1930s, and 1990s.

World War I

The economy was critically hurt by the German seizure of major

industrial areas in the northeast. While the occupied area in 1913

contained only 14% of France's industrial workers, it produced 58% of

the steel, and 40% of the coal. Considerable relief came with the massive influx of American food, money and raw materials in 1917-1928.

French credit collapsed in 1916 and Britain began loaning large sums to Paris. The J.P. Morgan & Co

bank in New York assumed control of French loans in the fall of 1916

and relinquished it to the U.S. government when the U.S. entered the war

in 1917.

On the other hand, the economy was helped by American loans which were

used to purchase foods and manufactured goods that allowed a decent

standard of living. The arrival of over a million American soldiers in

1918 brought heavy spending for food and construction materials. Labor

shortages were in part alleviated by the use of volunteer and forced

labor from the colonies.

The war damages amounted to about 113% of the GDP of 1913,

chiefly the destruction of productive capital and housing. The national

debt rose from 66% of GDP in 1913 to 170% in 1919, reflecting the heavy

use of bond issues to pay for the war. Inflation was severe, with the

franc losing over half its value against the British pound.

1919–1929

At the Paris Peace Conference, 1919,

vengeance against defeated Germany was the main French theme. France

demanded full payment by Germany of the damages it imposed in the

German-occupied areas. It also wanted the full cost of postwar veterans

benefits. Prime Minister Clemenceau was largely effective against the

moderating influences of the British and Americans. France obtained

large (but unspecified) reparations, regained Alsace-Lorraine and obtained mandates to rule parts of former German colonies in Africa.

In January 1923 as a response to the failure of the German to

ship enough coal as part of its reparations, France (and Belgium)

occupied the industrial region of the Ruhr.

Germany responded with passive resistance including printing vast

amounts of marks to pay for the occupation, thereby causing runaway

inflation. Inflation heavily damaged the German middle class (because

their bank accounts became worthless) but it also damaged the French

franc. France fomented a separatist movement pointing to an independent

buffer state, but it collapsed after some bloodshed. The intervention

was a failure, and in summer 1924 France accepted the American solution

to the reparations issues, as expressed in the Dawes Plan.

Great Depression

The worldwide decline after 1929 affected France a bit later than other countries, hitting around 1931.

The depression was relatively mild: unemployment peaked under 5%, the

fall in production was at most 20% below the 1929 output; there was no

banking crisis.

But the depression also lasted longer in France than in most other

countries. Like many other countries, France had introduced the gold

standard in the nineteenth century, meaning that it was generally

possible to exchange bank notes for gold. Unlike other countries (e.g.

Great Britain, which abandoned the gold standard in 1931), France stuck

to the gold standard until 1936, which caused a number of problems in

times of recession and deflation. France lost competitiveness relative

to Great Britain, because the latter was able to offer its products at a

cheaper price due to the devaluation of its currency after leaving the

gold standard.

Furthermore, terminating fixed exchange rate regimes opened up

opportunities for expansive monetary policy and thus influenced

consumers’ expectations of future inflation, which was crucial for

domestic demand. The French economy only started to recover when France

abandoned the gold standard.

However, the depression had some effects on the local economy, and partly explains the February 6, 1934 riots and even more the formation of the Popular Front, led by SFIO socialist leader Léon Blum, which won the elections in 1936.

France's relatively high degree of self-sufficiency meant the damage was considerably less than in nations like Germany.

Popular Front: 1936

Hardship and unemployment were high enough to lead to rioting and the rise of the socialist Popular Front, which won the 1936 elections with a coalition of Socialists and Radicals, and support from the Communists. Léon Blum became the first Socialist prime minister.

The election brought a massive wave of strikes, with involving 2

million workers, and their seizure of many factories and stores. The

strikes were spontaneous and unorganized, but nevertheless the business

community panicked and met secretly with Blum, Who negotiated a series

of reforms, and then gave labor unions the credit for the Matignon Accords. The new laws:

- confirmed the right to strike

- generalised collective bargaining

- enacted the law mandating 12 days of paid annual leave

- enacted the law limiting the working week to 40 hours (outside of overtime)

- raised wages (15% for the lowest-paid workers, and 7% for the relatively well-paid)

- stipulated that employers would recognise shop stewards.

- ensured that there would be no retaliation against strikers.

- created a national Office du blé (Grain Board or Wheat Office, through which the government helped to market agricultural produce at fair prices for farmers) to stabilise prices and curb speculation

- nationalised the arms industries

- made loans to small and medium-sized industries

- began a major public works programme

- raised the pay, pensions, and allowances of public-sector workers

- The 1920 Sales Tax, opposed by the Left as a tax on consumers, was abolished and replaced by a production tax, which was considered to be a tax on the producer instead of the consumer.

Blum persuaded the workers to accept pay raises and go back to work.

Wages increased sharply, in two years the national average was up 48

percent. However inflation also rose 46%. The imposition of the 40-hour

week proved highly inefficient, as industry had a difficult time

adjusting to it.

The economic confusion hindered the rearmament effort, and the rapid

growth of German armaments alarmed Blum. He launched a major program to

speed up arms production. The cost forced the abandonment of the social

reform programs of the popular front had counted heavily on.

Legacy of Popular Front

Economic

historians point to numerous bad financial and economic policies, such

as delayed devaluation of the franc, which made French exports

uncompetitive.

Economists especially emphasize the bad effects of the 40-hour week,

which made overtime illegal, forcing employers to stop work or to

replace their best workers with inferior and less experienced workers

when that 40-hour limit was reached. More generally the argument is

made that France could not afford the labor reforms, in the face of poor

economic conditions, the fears of the business community and the threat

of Nazi Germany.

Some historians have judged the Popular Front a failure in terms

of economics, foreign policy, and long-term political stability.

"Disappointment and failure," says Jackson, "was the legacy of the

Popular Front." However, it did inspire later reformers who set up the modern French welfare state.

Vichy France, 1940–1944

Conditions in Vichy France

under German occupation were very harsh, because the Germans stripped

France of millions of workers (as prisoners of war and "voluntary"

workers), and as well stripped much of the food supply, while demanding

heavy cash payments. It was a period of severe economic hardship under a

totalitarian government.

Vichy rhetoric exalted the skilled laborer and small businessman.

In practice, however, the needs of artisans for raw materials was

neglected in favor of large businesses.

The General Committee for the Organization of Commerce (CGOC) was a

national program to modernize and professionalize small business.

In 1940 the government took direct control of all production,

which was synchronized with the demands of the Germans. It replaced free

trade unions with compulsory state unions that dictated labor policy

without regard to the voice or needs of the workers. The centralized,

bureaucratic control of the French economy was not a success, as German

demands grew heavier and more unrealistic, passive resistance and

inefficiencies multiplied, and Allied bombers hit the rail yards;

however, Vichy made the first comprehensive long-range plans for the

French economy. The government had never before attempted a

comprehensive overview. De Gaulle's Provisional Government in 1944-45,

quietly used the Vichy plans as a base for its own reconstruction

program. The Monnet Plan of 1946 was closely based on Vichy plans.

Thus both teams of wartime and early postwar planners repudiated prewar

laissez-faire practices and embraced the cause of drastic economic

overhaul and a planned economy.

Forced labor

Nazi

Germany kept nearly 2.5 million French Army POWs as forced laborers

throughout the war. They added compulsory (and volunteer) workers from

occupied nations, especially in metal factories. The shortage of

volunteers led the Vichy government to pass a law in September 1941 that

effectively deported workers to Germany, where, they constituted 17% of

the labor force by August 1943. The largest number worked in the giant Krupp

steel works in Essen. Low pay, long hours, frequent bombings, and

crowded air raid shelters added to the unpleasantness of poor housing,

inadequate heating, limited food, and poor medical care, all compounded

by harsh Nazi discipline. They finally returned home in the summer of

1945. The forced labour draft encouraged the French Resistance and undermined the Vichy government.

Food shortages

Civilians suffered shortages of all varieties of consumer goods.

The rationing system was stringent but badly mismanaged, leading to

produced malnourishment, black markets, and hostility to state

management of the food supply. The Germans seized about 20% of the

French food production, which caused severe disruption to the household

economy of the French people.

French farm production fell in half because of lack of fuel, fertilizer

and workers; even so the Germans seized half the meat, 20 percent of

the produce, and 2 percent of the champagne.

Supply problems quickly affected French stores which lacked most

items. The government answered by rationing, but German officials set

the policies and hunger prevailed, especially affecting youth in urban

areas. The queues lengthened in front of shops. Some people—including

German soldiers—benefited from the black market,

where food was sold without tickets at very high prices. Farmers

especially diverted meat to the black market, which meant that much less

for the open market. Counterfeit food tickets were also in circulation.

Direct buying from farmers in the countryside and barter against

cigarettes became common. These activities were strictly forbidden,

however, and thus carried out at the risk of confiscation and fines.

Food shortages were most acute in the large cities. In the more remote

country villages, however, clandestine slaughtering, vegetable gardens

and the availability of milk products permitted better survival. The

official ration provided starvation level diets of 1300 or fewer

calories a day, supplemented by home gardens and, especially, black

market purchases.

From 1944

Historical GDP growth of France from 1961 to 2016 and the latter part of Les Trente Glorieuses.

The great hardships of wartime, and of the immediate post-war period,

were succeeded by a period of steady economic development, in France,

now often fondly recalled there as The Thirty Glorious Years (Les Trente Glorieuses).

Alternating policies of "interventionist" and "free market" ideas

enabled the French to build a society in which both industrial and

technological advances could be made but also worker security and

privileges established and protected. In the year 1946 France signed a

treaty with US that waved off a large part of its debt. It was known as The Blum-Byrnes agreement

(in French accord Blum-Byrnes) which was a French-American agreement,

signed May 28, 1946 by the Secretary of State James F. Byrnes and

representatives of the French government Léon Blum and Jean Monnet. This

agreement erased part of the French debt to the United States after the

Second World War (2 billion dollars).

By the end of the 20th century, France once again was among the

leading economic powers of the world, although by the year 2000 there

already was some fraying around the edges: people in France and

elsewhere were asking whether France alone, without becoming even more

an integral part of a pan-European economy, would have sufficient market

presence to maintain its position, and that worker security and those

privileges, in an increasingly "Globalized" and "transnational" economic world.

Reconstruction and the Welfare State

Reconstruction began at the end of the war, in 1945, and confidence in the future was brought back. With the baby boom

(which had started as soon as 1942) the birthrate surged rapidly. It

took several years to fix the damages caused by the war – battles and

bombing had destroyed several cities, factories, bridges, railway

infrastructures. 1,200,000 buildings were destroyed or damaged.

In 1945, the provisional government of the French Republic, led by Charles de Gaulle and made up of communists, socialists and gaullists, nationalized key economic sectors (energy, air transport, savings banks, assurances) and big companies (e.g. Renault), with the creation of Social Security and of works councils. A welfare state was set up. Economic planning was initiated with the Commissariat général du Plan in 1946, led by Jean Monnet.

The first « Plan de modernisation et d’équipement », for the 1947-1952

period, focused on basic economic activities (energy, steel, cement,

transports, agriculture equipment); the second Plan (1954–1957) had

broader aims: housing construction, urban development, scientific

research, manufacturing industries.

The debts left over from the First World War, whose payment had been suspended since 1931, was renegotiated in the Blum-Byrnes agreement of 1946. The U.S. forgave all $2.8 billion in debt, and gave France a new loan of $650 million. In return French negotiator Jean Monnet

set out the French five-year plan for recovery and development.

American films were now allowed in French cinemas three weeks per month.

Nationalized industries

Nationalization

of major industries took place in the 1930s and 1940s, but was never

complete. The railways were nationalized in 1937 because they were

losing money, but were strategically important. Likewise the

aeronautics and armaments industries were nationalized. During the war,

the Vichy government froze wages, froze prices, controlled external

trade and supervise distribution of raw materials to the manufacturing

sector. The French economy accepted increasing levels of

nationalization without major political opposition. After the war the

power industry, gas, and electricity were nationalized in 1946, with the

goal of bringing increased efficiency. Banking and insurance were

nationalized along with iron and steel. However oil was not considered

so important, and was not nationalized. Enlarge role of government

necessitated systematic national planning, which was a key feature of

the postwar industries.

Monnet Plan

To aid the rebuilding of the French economy, the value of stolen resources were recovered from defeated Germany under the Monnet Plan. As part of this policy, German factories were disassembled and moved to France, and the coal-rich industrial Saar Protectorate was occupied by France, as had been done post-World War I, in the Territory of the Saar Basin.

Thus in the 1947–1956 period, France benefited from the resources and

production of the Saar, and continued to extract coal from the Warndt

coal deposit until 1981. The Saarland reunited with Germany in 1957, and resolution of its situation led to the formation of the European Coal and Steel Community, precursor to the European Union, which played a significant role in Europe and France's economy in the later post-war period.

Economic recovery

Although

the economic situation in France was very grim in 1945, resources did

exist and the economy regained normal growth by the 1950s. The US government had planned a major aid program, but it unexpectedly ended Lend Lease

in late summer 1945, and additional aid was stymied by Congress in

1945-46. However there were $2 billion in American loans. France

managed to regain its international status thanks to a successful

production strategy, a demographic spurt, and technical and political

innovations. Conditions varied from firm to firm. Some had been

destroyed or damaged, nationalized or requisitioned, but the majority

carried on, sometimes working harder and more efficiently than before

the war. Industries were reorganized on a basis that ranged from

consensual (electricity) to conflictual (machine tools), therefore

producing uneven results. Despite strong American pressure through the

ERP, there was little change in the organization and content of the

training for French industrial managers. This was mainly due to the

reticence of the existing institutions and the struggle among different

economic and political interest groups for control over efforts to

improve the further training of practitioners.

The Monnet Plan

provided a coherent framework for economic policy, and it was strongly

supported by the Marshall Plan. It was inspired by moderate, Keynesian

free-trade ideas rather than state control. Although relaunched in an

original way, the French economy was about as productive as comparable

West European countries.

The United States helped revive the French economy with the Marshall Plan

whereby it gave France $2.3 billion with no repayment. France agreed to

reduce trade barriers and modernize its management system. The total of

all American grants and credits to France, 1946–53, came to $4.9

billion, and low-interest loans added another $2 billion.

The Marshall Plan set up intensive tours of American industry.

France sent 500 missions with 4700 businessmen and experts to tour

American factories, farms, stores and offices. They were especially

impressed with the prosperity of American workers, and how they could

purchase an inexpensive new automobile for nine months work, compared to

30 months in France.

Some French businesses resisted Americanization, but others seized upon

it to attract American investments and build a larger market. The

industries that were most Americanized included chemicals, oil,

electronics, and instrumentation. They were the most innovative, and

most profitable sectors.

Claude Fohlen argues that:

- In all then, France received 7,000 million dollars, which were used either to finance the imports needed to get the economy off the ground again or to implement the Monnet Plan....Without the Marshall Plan, however, the economic recovery would have been a much slower process – particularly in France, where American aid provided funds for the Monnet Plan and thereby restored equilibrium in the equipment industries, which govern the recovery of consumption, and opened the way... To continuing further growth. This growth was affected by a third factor... decolonization.

Les Trente Glorieuses: 1947–1973

Between 1947 and 1973, France went through a booming period (5% per year in average) dubbed by Jean Fourastié Trente Glorieuses, title of a book published in 1979.

The economic growth is mainly due to productivity gains and to an

increase in the number of working hours. Indeed, the working population

was growing very slowly, the baby boom

being offset by the extension of the time dedicated to studies.

Productivity gains came from the catching up with the United States. In

1950, the average income in France was 55% of an American and reached

80% in 1973. Among the major nations, only Japan and Spain had faster

growth in this era than France.

Insisting that the period was not that of an economic miracle,