Petro-Islam is a neologism used to refer to the international propagation of the extremist and fundamentalist interpretations of Sunni Islam derived from the doctrines of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a Sunni Muslim preacher, scholar, reformer and theologian from Uyaynah in the Najd region of the Arabian Peninsula, eponym of the Islamic revivalist movement known as Wahhabism. This movement has been favored by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the other Arab states of the Persian Gulf.

Its name derives from source of the funding, petroleum exports, that spread it through the Muslim world after the Yom Kippur War The term is sometimes called "pejorative" or a "nickname". According to Sandra Mackey the term was coined by Fouad Ajami. It has been used by French political scientist Gilles Kepel, Bangladeshi scholar Imtiyaz Ahmed, and Egyptian philosopher Fouad Zakariyya, among others.

Usage and definitions

The use of the term to refer to "Wahhabism", the dominant interpretation of Islam in Saudi Arabia, is widespread but not universal. Variations on or different uses of the term include:

- Use of resources by Saudi Arabia "to project itself as a major player in the Muslim world": the distribution of large sums of money from public and private sources in Saudi Arabia to advance Wahhabi doctrines and pursue the Saudi Arabian foreign policy.

- Attempts by the Saudi rulers to use both Islam and its wealth to win the loyalty of the Muslim world.

- Diplomatic, political, economic, and religious policies promoted by Saudi Arabia.

- The type of Islam favored by petroleum-exporting Muslim-majority countries, particularly the other Gulf monarchies (United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, etc.), not just Saudi Arabia.

- A "hugely successful" enterprise made up of a "colossal ensemble" of media and other cultural organs that has broken the "secularist and nationalist" monopoly of the state on culture, media and, "to a lesser extent", education; and is supported by both Islamists and socially conservative business "elements", who opposed the Arab nationalist ideologies of Nasserism and Baathism.

- More conservative Islamic cultural practices (separation of the sexes, wearing of the hijab or a more complete hijab) brought back (to other Muslim states, such as Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc.) from Gulf oil states by migrant workers.

- A term used by secularists, particularly in Egypt, to refer to efforts to require the enforcement of sharia (Islamic law).

- An Islamic interpretation that is "anti-woman, anti-intellectual, anti-progress, and anti-science... largely funded by the Saudis and Kuwaitis."

Background

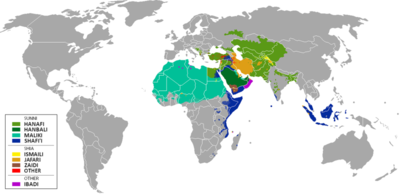

One scholar who spelled out the idea of petro-Islam in some detail is Gilles Kepel. According to Kepel, prior to the 1973 oil embargo, religion throughout the Muslim world was "dominated by national or local traditions rooted in the piety of the common people." Clerics looked to their different schools of fiqh (the four Sunni Madhhabs: Hanafi in the Turkish zones of South Asia, Maliki in Africa, Shafi'i in Southeast Asia, plus Shi'a Ja'fari, and "held Saudi inspired puritanism" (using another school of fiqh, Hanbali) in "great suspicion on account of its sectarian character," according to Gilles Kepel.

While the 1973 War (also called the Yom Kippur War) was started by Egypt and Syria to take back land won by Israel in 1967, the "real victors" of the war were the Arab "oil-exporting countries", (according to Gilles Kepel), whose embargo against Israel's western allies stopped Israel's counter offensive.

The embargo's political success enhanced the prestige of those who embargoed and the reduction in the global supply of oil sent oil prices soaring (from $3 per barrel to nearly $12) and with them, oil exporter revenues. That put Muslim oil exporting states in a "clear position of dominance within the Muslim world." The most dominant was Saudi Arabia, the largest exporter by far (see bar chart).

Saudi Arabians viewed their oil wealth not as an accident of geology or history but connected to religion, a blessing by God of them, to "be solemnly acknowledged and lived up to" with pious behavior.

With its new wealth the rulers of Saudi Arabia sought to replace nationalist movements in the Muslim world with Islam, to bring Islam "to the forefront of the international scene," and to unify Islam worldwide under the "single creed" of Wahhabism, paying particular attention to Muslims who had immigrated to the West (a "special target").

Influence of "Petro-dollars"

According to scholar Gilles Kepel, (who devoted a chapter of his book Jihad to the subject -- "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism"), in the years immediately after the 1973 War, 'petro-Islam' was a "sort of nickname" for a "constituency" of Wahhabi preachers and Muslim intellectuals who promoted "strict implementation of the sharia [Islamic law] in the political, moral and cultural spheres."

In the coming decades, Saudi Arabia's interpretation of Islam became influential (according to Kepel) through

- the spread of Wahhabi religious doctrines via Saudi charities; an

- increased migration of Muslims to work in Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf states; and

- a shift in the balance of power among Muslim states toward the oil-producing countries.

Author Sandra Mackey describes the use of petrodollars on facilities for the hajj such as by leveling hill peaks to make room for tents, providing electricity for tents and cooling pilgrims with ice and air conditioning, as part of "Petro-Islam", which she describes as a way of building the Muslim faithful's loyalty toward the Saudi government.

Religious funding

The Saudi ministry for religious affairs printed and distributed millions of Qurans free of charge, along with doctrinal texts that followed the Wahhabi interpretation. In mosques throughout the world "from the African plains to the rice paddies of Indonesia and the Muslim immigrant high-rise housing projects of European cities, the same books could be found," paid for by Saudi Arabian government.

Imtiyaz Ahmed, a religious scholar and professor of International Relations at University of Dhaka sees changes in religious practices in Bangladesh as linked to Saudi Arabia's efforts to promote Wahhabism through the financial help it provides countries like Bangladesh. The Mawlid, the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad's birthday and formerly "an integral part of Bangladeshi culture" is no longer popular, while black burqas for women are much more so. The discount on the price of oil imports Bangladesh receives does not "come free", according to Ahmed. "Saudi Arabia is giving oil, Saudi Arabia would definitely want that some of their ideas to come with oil."

Mosques

More than 1,500 mosques were built around the world from 1975 to 2000 paid for by Saudi public funds. The Saudi-headquartered and financed Muslim World League played a pioneering role in supporting Islamic associations, mosques, and investment plans for the future. It opened offices in "every area of the world where Muslims lived." The process of financing mosques usually involved presenting a local office of the Muslim World League with evidence of the need for a mosque/Islamic center to obtain the offices 'recommendation' (tazkiya) to "a generous donor within the kingdom or one of the emirates."

Saudi-financed mosques were generally built using marble 'international style' design and green neon lighting, in a break with most local Islamic architectural traditions, but following Wahhabi ones.

Islamic banking

One mechanism for the redistribution of (some) oil revenues from Saudi Arabia and other Muslim oil-exporters, to the poorer Muslim nations of African and Asia, was the Islamic Development Bank. Headquartered in Saudi Arabia, it opened for business in 1975. Its lenders and borrowers were member states of Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) and it strengthened "Islamic cohesion" between them.

Saudi Arabians also helped establish Islamic banks with private investors and depositors. DMI (Dar al-Mal al-Islami: the House of Islamic Finance), founded in 1981 by Prince Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud, and the Al Baraka group, established in 1982 by Sheik Saleh Abdullah Kamel (a Saudi billionaire), were both transnational holding companies.

Migration

By 1975, over one million workers, from unskilled country people to experienced professors – from Sudan, Pakistan, India, Southeast Asia, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria – had moved to Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf states to work and returned after a few years with savings. Most of the workers were Arab and most were Muslim. Ten years later the number had increased to 5.15 million and Arabs were no longer in the majority. 43% (mostly Muslims) came from the Indian subcontinent. In one country, Pakistan, in a single year, (1983),

the money sent home by Gulf emigrants amounted to $3 billion, compared with a total of $735 million given to the nation in foreign aid.... The underpaid petty functionary of yore could now drive back to his hometown at the wheel of a foreign car, build himself a house in a residential suburb, and settle down to invest his savings or engage in trade... he owed nothing to his home state, where he could never have earned enough to afford such luxuries.

Muslims who had moved to Saudi Arabia, or other "oil-rich monarchies of the peninsula" to work, often returned to their poor home country following religious practice more intensely, particularly practices of Wahhabi Muslims. Having "grown rich in this Wahhabi milieu", it was not surprising that the returning Muslims believed that there was a connection between that milieu and "their material prosperity" and that when they returned, they followed religious practices more intensely, which followed Wahhabi tenants. Kepel gives examples of migrant workers returning home with new affluence, asking to be addressed by servants as "hajja" rather than "Madame" (the old bourgeois custom). Another imitation of Saudi Arabia adopted by affluent migrant workers was increased segregation of the sexes, including shopping areas.

State leadership

In the 1950s and 1960s Gamal Abdul-Nasser, the leading exponent of Arab nationalism and the president of the Arab world's largest country had great prestige and popularity.

However, in 1967 Nasser led the Six-Day War against Israel which ended not in the elimination of Israel but in the decisive defeat of the Arab forces and loss of a substantial chunk of Egyptian territory. This defeat, combined with the economic stagnation from which Egypt suffered, were contrasted with the perceived victory of the October 1973 war whose pious battle cry of Allahu Akbar replaced "Land! Sea! Air!" slogan of the 1967 war, and with the enormous wealth of the resolutely non-nationalist Saudi Arabia.

This changed "the balance of power among Muslim states" toward Saudi Arabia and other oil-exporting countries. gaining as Egypt lost influence. The oil-exporters emphasized "religious commonality" among Arabs, Turks, Africans, and Asians, and downplayed "differences of language, ethnicity, and nationality." The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, whose permanent Secretariat is located in Jeddah in Western Saudi Arabia, was founded after the 1967 war.

Criticism

At least one observer, The New Yorker magazine's investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, has suggested that petro-Islam is being spread by those whose motivations are less than earnest or pious. Petro-Islam funding following the Gulf War, according to Hersh, "amounts to protection money" from the Saudi regime "to fundamentalist groups that wish to overthrow it."

Egyptian existentialist Fouad Zakariyya has accused purveyors of Petro-Islam as having as their objective the protection of the oil wealth and "social relations" of the "tribal societies that possess the lion's share of this wealth," at the expense of the long-term development of the region and the majority of its people. He further states that it is a "brand of Islam" that bills itself as "pure" but rather than being the Islam of the early Muslims has "never" been "seen before in history".

Authors who criticize the "thesis" of Petro-Islam itself (that petrodollars have had a significant effect on Muslim beliefs and practices) include Joel Beinin and Joe Stork. They argue that in Egypt, Sudan and Jordan, "Islamic movements have demonstrated a high level of autonomy from their original patrons." The strength and growth of Muslim Brotherhood and other forces of conservative political Islam in Egypt can be explained, according to Beinin and Stork, by internal forces: the historical strength of the Muslim Brotherhood, sympathy for the "martyred" Sayyid Qutb, anger with the "autocratic tendencies" and the failed promises of prosperity of the Sadat government.