A multi-level stack interchange, buildings, houses, and park in Shanghai, China.

Civil engineering is a professional engineering

discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of

the physical and naturally built environment, including public works

such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewerage systems,

pipelines, structural components of buildings, and railways.

Civil engineering is traditionally broken into a number of

sub-disciplines. It is considered the second-oldest engineering

discipline after military engineering, and it is defined to distinguish non-military engineering from military engineering.

Civil engineering takes place in the public sector from municipal

through to national governments, and in the private sector from

individual homeowners through to international companies.

History

Civil engineering as a discipline

Civil

engineering is the application of physical and scientific principles

for solving the problems of society, and its history is intricately

linked to advances in the understanding of physics and mathematics

throughout history. Because civil engineering is a wide-ranging

profession, including several specialized sub-disciplines, its history

is linked to knowledge of structures, materials science, geography,

geology, soils, hydrology, environment, mechanics and other fields.

Throughout ancient and medieval history most architectural design and construction was carried out by artisans, such as stonemasons and carpenters, rising to the role of master builder. Knowledge was retained in guilds

and seldom supplanted by advances. Structures, roads, and

infrastructure that existed were repetitive, and increases in scale were

incremental.

One of the earliest examples of a scientific approach to physical

and mathematical problems applicable to civil engineering is the work

of Archimedes in the 3rd century BC, including Archimedes Principle, which underpins our understanding of buoyancy, and practical solutions such as Archimedes' screw. Brahmagupta,

an Indian mathematician, used arithmetic in the 7th century AD, based

on Hindu-Arabic numerals, for excavation (volume) computations.

Civil engineering profession

Engineering has been an aspect of life since the beginnings of human

existence. The earliest practice of civil engineering may have commenced

between 4000 and 2000 BC in ancient Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization, and Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq) when humans started to abandon a nomadic

existence, creating a need for the construction of shelter. During this

time, transportation became increasingly important leading to the

development of the wheel and sailing.

Leonhard Euler developed the theory explaining the buckling of columns

Until modern times there was no clear distinction between civil

engineering and architecture, and the term engineer and architect were

mainly geographical variations referring to the same occupation, and

often used interchangeably. The construction of pyramids

in Egypt (circa 2700–2500 BC) were some of the first instances of large

structure constructions. Other ancient historic civil engineering

constructions include the Qanat water management system (the oldest is older than 3000 years and longer than 71 km,) the Parthenon by Iktinos in Ancient Greece (447–438 BC), the Appian Way by Roman engineers (c. 312 BC), the Great Wall of China by General Meng T'ien under orders from Ch'in Emperor Shih Huang Ti (c. 220 BC) and the stupas constructed in ancient Sri Lanka like the Jetavanaramaya and the extensive irrigation works in Anuradhapura. The Romans developed civil structures throughout their empire, including especially aqueducts, insulae, harbors, bridges, dams and roads.

A Roman aqueduct [built circa 19 BC] near Pont du Gard, France

Chichen Itza was a large pre-Columbian city in Mexico built by the Maya people of the Post Classic. The northeast column temple also covers a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 metres (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

In the 18th century, the term civil engineering was coined to

incorporate all things civilian as opposed to military engineering. The first self-proclaimed civil engineer was John Smeaton, who constructed the Eddystone Lighthouse.

In 1771 Smeaton and some of his colleagues formed the Smeatonian

Society of Civil Engineers, a group of leaders of the profession who met

informally over dinner. Though there was evidence of some technical

meetings, it was little more than a social society.

John Smeaton, the "father of civil engineering"

In 1818 the Institution of Civil Engineers was founded in London, and in 1820 the eminent engineer Thomas Telford

became its first president. The institution received a Royal Charter in

1828, formally recognising civil engineering as a profession. Its

charter defined civil engineering as:

...the art of directing the great sources of power in nature for the use and convenience of man, as the means of production and of traffic in states, both for external and internal trade, as applied in the construction of roads, bridges, aqueducts, canals, river navigation and docks for internal intercourse and exchange, and in the construction of ports, harbours, moles, breakwaters and lighthouses, and in the art of navigation by artificial power for the purposes of commerce, and in the construction and application of machinery, and in the drainage of cities and towns.

Civil engineering education

The first private college to teach civil engineering in the United States was Norwich University, founded in 1819 by Captain Alden Partridge. The first degree in civil engineering in the United States was awarded by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1835. The first such degree to be awarded to a woman was granted by Cornell University to Nora Stanton Blatch in 1905.

In the UK during the early 19th century, the division between civil engineering and military engineering (served by the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich),

coupled with the demands of the Industrial Revolution, spawned new

engineering education initiatives: the Class of Civil Engineering and

Mining was founded at King's College London in 1838, mainly as a response to the growth of the railway system and the need for more qualified engineers, the private College for Civil Engineers in Putney was established in 1839, and the UK's first Chair of Engineering was established at the University of Glasgow in 1840.

Education

Civil engineers typically possess an academic degree in civil engineering. The length of study is three to five years, and the completed degree is designated as a bachelor of technology, or a bachelor of engineering. The curriculum generally includes classes in physics, mathematics, project management,

design and specific topics in civil engineering. After taking basic

courses in most sub-disciplines of civil engineering, they move onto

specialize in one or more sub-disciplines at advanced levels. While an

undergraduate degree (BEng/BSc) normally provides successful students

with industry-accredited qualification, some academic institutions offer

post-graduate degrees (MEng/MSc), which allow students to further

specialize in their particular area of interest.

Surveying students with professor at the Helsinki University of Technology in the late 19th century.

Practicing engineers

In most countries, a bachelor's degree in engineering represents the first step towards professional certification, and a professional body

certifies the degree program. After completing a certified degree

program, the engineer must satisfy a range of requirements (including

work experience and exam requirements) before being certified. Once

certified, the engineer is designated as a professional engineer (in the United States, Canada and South Africa), a chartered engineer (in most Commonwealth countries), a chartered professional engineer (in Australia and New Zealand), or a European engineer (in most countries of the European Union).

There are international agreements between relevant professional bodies

to allow engineers to practice across national borders.

The benefits of certification vary depending upon location. For example, in the United States and Canada, "only a licensed professional engineer

may prepare, sign and seal, and submit engineering plans and drawings

to a public authority for approval, or seal engineering work for public

and private clients." This requirement is enforced under provincial law such as the Engineers Act in Quebec.

No such legislation has been enacted in other countries including

the United Kingdom. In Australia, state licensing of engineers is

limited to the state of Queensland. Almost all certifying bodies maintain a code of ethics which all members must abide by.

Engineers must obey contract law

in their contractual relationships with other parties. In cases where

an engineer's work fails, they may be subject to the law of tort of negligence, and in extreme cases, criminal charges. An engineer's work must also comply with numerous other rules and regulations such as building codes and environmental law.

Sub-disciplines

The Akashi Kaikyō Bridge in Japan, currently the world's longest suspension span.

There are a number of sub-disciplines within the broad field of civil

engineering. General civil engineers work closely with surveyors and

specialized civil engineers to design grading, drainage, pavement,

water supply, sewer service, dams, electric and communications supply.

General civil engineering is also referred to as site engineering, a

branch of civil engineering that primarily focuses on converting a tract

of land from one usage to another. Site engineers spend time visiting

project sites, meeting with stakeholders, and preparing construction

plans. Civil engineers apply the principles of geotechnical engineering,

structural engineering, environmental engineering, transportation

engineering and construction engineering to residential, commercial,

industrial and public works projects of all sizes and levels of

construction.

Coastal engineering

Oosterscheldekering, a storm surge barrier in the Netherlands.

Coastal engineering is concerned with managing coastal areas.

In some jurisdictions, the terms sea defense and coastal protection mean

defense against flooding and erosion, respectively. The term coastal

defense is the more traditional term, but coastal management has become

more popular as the field has expanded to techniques that allow erosion

to claim land.

Construction engineering

Construction engineering involves planning and execution,

transportation of materials, site development based on hydraulic,

environmental, structural and geotechnical engineering. As construction

firms tend to have higher business risk than other types of civil

engineering firms do, construction engineers often engage in more

business-like transactions, for example, drafting and reviewing

contracts, evaluating logistical operations, and monitoring prices of supplies.

Earthquake engineering

Earthquake engineering involves designing structures to

withstand hazardous earthquake exposures. Earthquake engineering is a

sub-discipline of structural engineering. The main objectives of

earthquake engineering are

to understand interaction of structures on the shaky ground; foresee

the consequences of possible earthquakes; and design, construct and

maintain structures to perform at earthquake in compliance with building codes.

Environmental engineering

Water pollution

Environmental engineering is the contemporary term for sanitary engineering,

though sanitary engineering traditionally had not included much of the

hazardous waste management and environmental remediation work covered by

environmental engineering. Public health engineering and environmental

health engineering are other terms being used.

Environmental engineering deals with treatment of chemical, biological, or thermal wastes, purification of water and air, and remediation

of contaminated sites after waste disposal or accidental contamination.

Among the topics covered by environmental engineering are pollutant

transport, water purification, waste water treatment, air pollution, solid waste treatment, and hazardous waste management. Environmental engineers administer pollution reduction, green engineering, and industrial ecology. Environmental engineers also compile information on environmental consequences of proposed actions.

Forensic engineering

Forensic engineering is the investigation of materials, products,

structures or components that fail or do not operate or function as

intended, causing personal injury or damage to property. The

consequences of failure are dealt with by the law of product liability.

The field also deals with retracing processes and procedures leading to

accidents in operation of vehicles or machinery. The subject is applied

most commonly in civil law cases, although it may be of use in criminal

law cases. Generally the purpose of a Forensic engineering investigation

is to locate cause or causes of failure with a view to improve

performance or life of a component, or to assist a court in determining

the facts of an accident. It can also involve investigation of

intellectual property claims, especially patents.

Geotechnical engineering

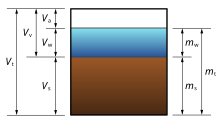

A phase diagram of soil indicating the weights and volumes of air, soil, water, and voids.

Geotechnical engineering studies rock and soil supporting civil engineering systems. Knowledge from the field of soil science, materials science, mechanics, and hydraulics is applied to safely and economically design foundations, retaining walls, and other structures. Environmental efforts to protect groundwater and safely maintain landfills have spawned a new area of research called geoenvironmental engineering.

Identification of soil properties presents challenges to geotechnical engineers. Boundary conditions

are often well defined in other branches of civil engineering, but

unlike steel or concrete, the material properties and behavior of soil

are difficult to predict due to its variability and limitation on investigation. Furthermore, soil exhibits nonlinear (stress-dependent) strength, stiffness, and dilatancy (volume change associated with application of shear stress), making studying soil mechanics all the more difficult. Geotechnical engineers frequently work with professional geologists and soil scientists.

Materials science and engineering

Materials science is closely related to civil engineering. It

studies fundamental characteristics of materials, and deals with

ceramics such as concrete and mix asphalt concrete, strong metals such

as aluminum and steel, and thermosetting polymers including polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) and carbon fibers.

Materials engineering involves protection and prevention

(paints and finishes). Alloying combines two types of metals to produce

another metal with desired properties. It incorporates elements of applied physics and chemistry. With recent media attention on nanoscience and nanotechnology,

materials engineering has been at the forefront of academic research.

It is also an important part of forensic engineering and failure analysis.

Structural engineering

Structural engineering is concerned with the structural design and structural analysis of buildings, bridges, towers, flyovers (overpasses), tunnels, off shore structures like oil and gas fields in the sea, aerostructure

and other structures. This involves identifying the loads which act

upon a structure and the forces and stresses which arise within that

structure due to those loads, and then designing the structure to

successfully support and resist those loads. The loads can be self

weight of the structures, other dead load, live loads, moving (wheel)

load, wind load, earthquake load, load from temperature change etc. The

structural engineer must design structures to be safe for their users

and to successfully fulfill the function they are designed for (to be serviceable). Due to the nature of some loading conditions, sub-disciplines within structural engineering have emerged, including wind engineering and earthquake engineering.

Design considerations will include strength, stiffness, and

stability of the structure when subjected to loads which may be static,

such as furniture or self-weight, or dynamic, such as wind, seismic,

crowd or vehicle loads, or transitory, such as temporary construction

loads or impact. Other considerations include cost, constructability,

safety, aesthetics and sustainability.

Surveying

A student using a dumpy level

Surveying is the process by which a surveyor measures certain

dimensions that occur on or near the surface of the Earth. Surveying

equipment, such as levels and theodolites, are used for accurate

measurement of angular deviation, horizontal, vertical and slope

distances. With computerisation, electronic distance measurement (EDM),

total stations, GPS surveying and laser scanning have to a large extent

supplanted traditional instruments. Data collected by survey measurement

is converted into a graphical representation of the Earth's surface in

the form of a map. This information is then used by civil engineers,

contractors and realtors to design from, build on, and trade,

respectively. Elements of a structure must be sized and positioned in

relation to each other and to site boundaries and adjacent structures.

Although surveying is a distinct profession with separate qualifications

and licensing arrangements, civil engineers are trained in the basics

of surveying and mapping, as well as geographic information systems. Surveyors also lay out the routes of railways, tramway tracks, highways, roads, pipelines and streets as well as position other infrastructure, such as harbors, before construction.

- Land surveying

In the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and most Commonwealth

countries land surveying is considered to be a separate and distinct

profession. Land surveyors

are not considered to be engineers, and have their own professional

associations and licensing requirements. The services of a licensed land

surveyor are generally required for boundary surveys (to establish the

boundaries of a parcel using its legal description) and subdivision

plans (a plot or map based on a survey of a parcel of land, with

boundary lines drawn inside the larger parcel to indicate the creation

of new boundary lines and roads), both of which are generally referred

to as Cadastral surveying.

BLM cadastral survey marker from 1992 in San Xavier, Arizona.

- Construction surveying

Construction surveying is generally performed by specialised

technicians. Unlike land surveyors, the resulting plan does not have

legal status. Construction surveyors perform the following tasks:

- Surveying existing conditions of the future work site, including topography, existing buildings and infrastructure, and underground infrastructure when possible;

- "lay-out" or "setting-out": placing reference points and markers that will guide the construction of new structures such as roads or buildings;

- Verifying the location of structures during construction;

- As-Built surveying: a survey conducted at the end of the construction project to verify that the work authorized was completed to the specifications set on plans.

Transportation engineering

Transportation engineering

is concerned with moving people and goods efficiently, safely, and in a

manner conducive to a vibrant community. This involves specifying,

designing, constructing, and maintaining transportation infrastructure

which includes streets, canals, highways, rail systems, airports, ports, and mass transit. It includes areas such as transportation design, transportation planning, traffic engineering, some aspects of urban engineering, queueing theory, pavement engineering, Intelligent Transportation System (ITS), and infrastructure management.

Municipal or urban engineering

The engineering of this roundabout in Bristol, England, attempts to make traffic flow free-moving

Lake Chapultepec

Municipal engineering is concerned with municipal infrastructure. This involves specifying, designing, constructing, and maintaining streets, sidewalks, water supply networks, sewers, street lighting, municipal solid waste management and disposal, storage depots for various bulk materials used for maintenance and public works (salt, sand, etc.), public parks and cycling infrastructure. In the case of underground utility

networks, it may also include the civil portion (conduits and access

chambers) of the local distribution networks of electrical and

telecommunications services. It can also include the optimizing of waste

collection and bus service

networks. Some of these disciplines overlap with other civil

engineering specialties, however municipal engineering focuses on the

coordination of these infrastructure networks and services, as they are

often built simultaneously, and managed by the same municipal authority.

Municipal engineers may also design the site civil works for large

buildings, industrial plants or campuses (i.e. access roads, parking

lots, potable water supply, treatment or pretreatment of waste water,

site drainage, etc.)

Water resources engineering

Water resources engineering is concerned with the collection and management of water (as a natural resource). As a discipline it therefore combines elements of hydrology, environmental science, meteorology, conservation, and resource management.

This area of civil engineering relates to the prediction and management

of both the quality and the quantity of water in both underground (aquifers)

and above ground (lakes, rivers, and streams) resources. Water resource

engineers analyze and model very small to very large areas of the earth

to predict the amount and content of water as it flows into, through,

or out of a facility. Although the actual design of the facility may be

left to other engineers.

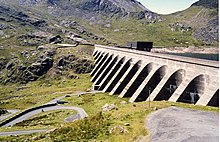

Hydraulic engineering is concerned with the flow and

conveyance of fluids, principally water. This area of civil engineering

is intimately related to the design of pipelines, water supply network, drainage facilities (including bridges, dams, channels, culverts, levees, storm sewers), and canals. Hydraulic engineers design these facilities using the concepts of fluid pressure, fluid statics, fluid dynamics, and hydraulics, among others.

The Falkirk Wheel in Scotland

Civil engineering systems

Civil

engineering systems is a discipline that promotes the use of systems

thinking to manage complexity and change in civil engineering within its

wider public context. It posits that the proper development of civil

engineering infrastructure requires a holistic,

coherent understanding of the relationships between all of the

important factors that contribute to successful projects while at the

same time emphasising the importance of attention to technical detail.

Its purpose is to help integrate the entire civil engineering project life cycle from conception, through planning, designing, making, operating to decommissioning.