| Insect | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top left: dance fly (Empis livida), long-nosed weevil (Rhinotia hemistictus), mole cricket (Gryllotalpa brachyptera), German wasp (Vespula germanica), emperor gum moth (Opodiphthera eucalypti), assassin bug (Harpactorinae) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Pancrustacea |

| Subphylum: | Hexapoda |

| Class: | Insecta Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Subgroups | |

|

See text.

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Insects or Insecta (from Latin insectum) are hexapod invertebrates and the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Definitions and circumscriptions vary; usually, insects comprise a class within the Arthropoda. As used here, the term Insecta is synonymous with Ectognatha. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed legs, compound eyes and one pair of antennae. Insects are the most diverse group of animals; they include more than a million described species and represent more than half of all known living organisms. The total number of extant species is estimated at between six and ten million; potentially over 90% of the animal life forms on Earth are insects. Insects may be found in nearly all environments, although only a small number of species reside in the oceans, which are dominated by another arthropod group, crustaceans.

Nearly all insects hatch from eggs. Insect growth is constrained by the inelastic exoskeleton and development involves a series of molts. The immature stages often differ from the adults in structure, habit and habitat, and can include a passive pupal stage in those groups that undergo four-stage metamorphosis. Insects that undergo three-stage metamorphosis lack a pupal stage and adults develop through a series of nymphal stages. The higher level relationship of the insects is unclear. Fossilized insects of enormous size have been found from the Paleozoic Era, including giant dragonflies with wingspans of 55 to 70 cm (22 to 28 in). The most diverse insect groups appear to have coevolved with flowering plants.

Adult insects typically move about by walking, flying, or sometimes swimming. As it allows for rapid yet stable movement, many insects adopt a tripedal gait in which they walk with their legs touching the ground in alternating triangles, composed of the front & rear on one side with the middle on the other side. Insects are the only invertebrates to have evolved flight, and all flying insects derive from one common ancestor. Many insects spend at least part of their lives under water, with larval adaptations that include gills, and some adult insects are aquatic and have adaptations for swimming. Some species, such as water striders, are capable of walking on the surface of water. Insects are mostly solitary, but some, such as certain bees, ants and termites, are social and live in large, well-organized colonies. Some insects, such as earwigs, show maternal care, guarding their eggs and young. Insects can communicate with each other in a variety of ways. Male moths can sense the pheromones of female moths over great distances. Other species communicate with sounds: crickets stridulate, or rub their wings together, to attract a mate and repel other males. Lampyrid beetles communicate with light.

Humans regard certain insects as pests, and attempt to control them using insecticides, and a host of other techniques. Some insects damage crops by feeding on sap, leaves, fruits, or wood. Some species are parasitic, and may vector diseases. Some insects perform complex ecological roles; blow-flies, for example, help consume carrion but also spread diseases. Insect pollinators are essential to the life cycle of many flowering plant species on which most organisms, including humans, are at least partly dependent; without them, the terrestrial portion of the biosphere would be devastated. Many insects are considered ecologically beneficial as predators and a few provide direct economic benefit. Silkworms produce silk and honey bees produce honey and both have been domesticated by humans. Insects are consumed as food in 80% of the world's nations, by people in roughly 3000 ethnic groups. Human activities also have effects on insect biodiversity.

Etymology

The word "insect" comes from the Latin word insectum, meaning "with a notched or divided body", or literally "cut into", from the neuter singular perfect passive participle of insectare, "to cut into, to cut up", from in- "into" and secare "to cut"; because insects appear "cut into" three sections. A calque of Greek ἔντομον [éntomon], "cut into sections", Pliny the Elder introduced the Latin designation as a loan-translation of the Greek word ἔντομος (éntomos) or "insect" (as in entomology), which was Aristotle's term for this class of life, also in reference to their "notched" bodies. "Insect" first appears documented in English in 1601 in Holland's translation of Pliny. Translations of Aristotle's term also form the usual word for "insect" in Welsh (trychfil, from trychu "to cut" and mil, "animal"), Serbo-Croatian (zareznik, from rezati, "to cut"), Russian (насекомое nasekomoje, from seč'/-sekat', "to cut"), etc.Definitions

The precise definition of the taxon Insecta and the equivalent English name "insect" varies; three alternative definitions are shown in the table.| Group | Alternative definitions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Collembola (springtails) | Insecta sensu lato =Hexapoda |

Entognatha (paraphyletic) |

Apterygota (wingless hexapods) (paraphyletic) |

| Protura (coneheads) | |||

| Diplura (two-pronged bristletails) | |||

| Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) | Insecta sensu stricto =Ectognatha | ||

| Zygentoma (silverfish) | |||

| Pterygota (winged insects) | Insecta sensu strictissimo | ||

In the broadest circumscription, Insecta sensu lato consists of all hexapods. Traditionally, insects defined in this way were divided into "Apterygota" (the first five groups in the table)—the wingless insects—and Pterygota—the winged insects. However, modern phylogenetic studies have shown that "Apterygota" is not monophyletic, and so does not form a good taxon. A narrower circumscription restricts insects to those hexapods with external mouthparts, and comprises only the last three groups in the table. In this sense, Insecta sensu stricto is equivalent to Ectognatha. In the narrowest circumscription, insects are restricted to hexapods that are either winged or descended from winged ancestors. Insecta sensu strictissimo is then equivalent to Pterygota. For the purposes of this article, the middle definition is used; insects consist of two wingless taxa, Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Zygentoma (silverfish), plus the winged or secondarily wingless Pterygota.

Phylogeny and evolution

Evolution has produced enormous variety in insects. Pictured are some possible shapes of antennae.

The evolutionary relationship of insects to other animal groups remains unclear.

Although traditionally grouped with millipedes and centipedes—possibly on the basis of convergent adaptations to terrestrialisation—evidence has emerged favoring closer evolutionary ties with crustaceans. In the Pancrustacea theory, insects, together with Entognatha, Remipedia, and Cephalocarida, make up a natural clade labeled Miracrustacea.

Insects form a single clade, closely related to crustaceans and myriapods.

Other terrestrial arthropods, such as centipedes, millipedes, scorpions, and spiders,

are sometimes confused with insects since their body plans can appear

similar, sharing (as do all arthropods) a jointed exoskeleton. However,

upon closer examination, their features differ significantly; most

noticeably, they do not have the six-legged characteristic of adult

insects.

The higher-level phylogeny of the arthropods continues to be a matter of debate and research. In 2008, researchers at Tufts University

uncovered what they believe is the world's oldest known full-body

impression of a primitive flying insect, a 300-million-year-old specimen

from the Carboniferous period. The oldest definitive insect fossil is the Devonian Rhyniognatha hirsti, from the 396-million-year-old Rhynie chert. It may have superficially resembled a modern-day silverfish

insect. This species already possessed dicondylic mandibles (two

articulations in the mandible), a feature associated with winged

insects, suggesting that wings may already have evolved at this time.

Thus, the first insects probably appeared earlier, in the Silurian period.

Four super radiations of insects have occurred: beetles (from about 300 million years ago), flies (from about 250 million years ago), moths and wasps (both from about 150 million years ago). These four groups account for the majority of described species. The flies and moths along with the fleas evolved from the Mecoptera.

The origins of insect flight

remain obscure, since the earliest winged insects currently known

appear to have been capable fliers. Some extinct insects had an

additional pair of winglets attaching to the first segment of the

thorax, for a total of three pairs. As of 2009, no evidence suggests the

insects were a particularly successful group of animals before they

evolved to have wings.

Late Carboniferous and Early Permian insect orders include both extant groups, their stem groups, and a number of Paleozoic

groups, now extinct. During this era, some giant dragonfly-like forms

reached wingspans of 55 to 70 cm (22 to 28 in), making them far larger

than any living insect. This gigantism may have been due to higher atmospheric oxygen

levels that allowed increased respiratory efficiency relative to today.

The lack of flying vertebrates could have been another factor. Most

extinct orders of insects developed during the Permian period that began

around 270 million years ago. Many of the early groups became extinct

during the Permian-Triassic extinction event, the largest mass extinction in the history of the Earth, around 252 million years ago.

The remarkably successful Hymenoptera appeared as long as 146 million years ago in the Cretaceous period, but achieved their wide diversity more recently in the Cenozoic era, which began 66 million years ago. A number of highly successful insect groups evolved in conjunction with flowering plants, a powerful illustration of coevolution.

Many modern insect genera developed during the Cenozoic. Insects from this period on are often found preserved in amber, often in perfect condition. The body plan, or morphology, of such specimens is thus easily compared with modern species. The study of fossilized insects is called paleoentomology.

Phylogeny

Taxonomy

Traditional morphology-based or appearance-based systematics have usually given the Hexapoda the rank of superclass, and identified four groups within it: insects (Ectognatha), springtails (Collembola), Protura, and Diplura, the latter three being grouped together as the Entognatha

on the basis of internalized mouth parts. Supraordinal relationships

have undergone numerous changes with the advent of methods based on

evolutionary history and genetic data. A recent theory is that the

Hexapoda are polyphyletic

(where the last common ancestor was not a member of the group), with

the entognath classes having separate evolutionary histories from the

Insecta. Many of the traditional appearance-based taxa have been shown to be paraphyletic, so rather than using ranks like subclass, superorder, and infraorder, it has proved better to use monophyletic

groupings (in which the last common ancestor is a member of the group).

The following represents the best-supported monophyletic groupings for

the Insecta.

Insects can be divided into two groups historically treated as

subclasses: wingless insects, known as Apterygota, and winged insects,

known as Pterygota. The Apterygota consist of the primitively wingless

order of the silverfish (Zygentoma). Archaeognatha make up the

Monocondylia based on the shape of their mandibles, while Zygentoma and Pterygota are grouped together as Dicondylia. The Zygentoma themselves possibly are not monophyletic, with the family Lepidotrichidae being a sister group to the Dicondylia (Pterygota and the remaining Zygentoma).

Paleoptera and Neoptera are the winged orders of insects differentiated by the presence of hardened body parts called sclerites,

and in the Neoptera, muscles that allow their wings to fold flatly over

the abdomen. Neoptera can further be divided into incomplete

metamorphosis-based (Polyneoptera and Paraneoptera)

and complete metamorphosis-based groups. It has proved difficult to

clarify the relationships between the orders in Polyneoptera because of

constant new findings calling for revision of the taxa. For example, the

Paraneoptera have turned out to be more closely related to the

Endopterygota than to the rest of the Exopterygota. The recent molecular

finding that the traditional louse orders Mallophaga and Anoplura are derived from within Psocoptera has led to the new taxon Psocodea. Phasmatodea and Embiidina have been suggested to form the Eukinolabia. Mantodea, Blattodea, and Isoptera are thought to form a monophyletic group termed Dictyoptera.

The Exopterygota likely are paraphyletic in regard to the

Endopterygota. Matters that have incurred controversy include

Strepsiptera and Diptera grouped together as Halteria based on a

reduction of one of the wing pairs—a position not well-supported in the

entomological community.

The Neuropterida are often lumped or split on the whims of the

taxonomist. Fleas are now thought to be closely related to boreid

mecopterans. Many questions remain in the basal relationships among endopterygote orders, particularly the Hymenoptera.

The study of the classification or taxonomy of any insect is called systematic entomology.

If one works with a more specific order or even a family, the term may

also be made specific to that order or family, for example systematic dipterology.

Evolutionary relationships

Insects are prey for a variety of organisms, including terrestrial

vertebrates. The earliest vertebrates on land existed 400 million years

ago and were large amphibious piscivores. Through gradual evolutionary change, insectivory was the next diet type to evolve.

Insects were among the earliest terrestrial herbivores and acted as major selection agents on plants. Plants evolved chemical defenses against this herbivory

and the insects, in turn, evolved mechanisms to deal with plant toxins.

Many insects make use of these toxins to protect themselves from their

predators. Such insects often advertise their toxicity using warning

colors. This successful evolutionary pattern has also been used by mimics.

Over time, this has led to complex groups of coevolved species.

Conversely, some interactions between plants and insects, like pollination, are beneficial to both organisms. Coevolution has led to the development of very specific mutualisms in such systems.

Diversity

A pie chart of described eukaryote species, showing just over half of these to be insects

Estimates on the total number of insect species, or those within specific orders,

often vary considerably. Globally, averages of these estimates suggest

there are around 1.5 million beetle species and 5.5 million insect

species, with about 1 million insect species currently found and

described.

Between 950,000–1,000,000 of all described species are insects,

so over 50% of all described eukaryotes (1.8 million) are insects (see

illustration). With only 950,000 known non-insects, if the actual number

of insects is 5.5 million, they may represent over 80% of the total.

As only about 20,000 new species of all organisms are described each

year, most insect species may remain undescribed, unless the rate of

species descriptions greatly increases. Of the 24 orders of insects,

four dominate in terms of numbers of described species; at least 670,000

identified species belong to Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera or Lepidoptera.

Insects with population trends documented by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, for orders Collembola, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Odonata, and Orthoptera. Of 203 insect species that had such documented population trends in 2013, 33% were in decline.

As of 2017, at least 66 insect species extinctions had been recorded

in the previous 500 years, which generally occurred on oceanic islands. Declines in insect abundance have been attributed to artificial lighting, land use changes such as urbanization or agricultural use, pesticide use, and invasive species.

Studies summarized in a 2019 review suggested a large proportion of

insect species are threatened with extinction in the 21st century.

Though ecologist Manu Sanders notes the 2019 review was biased by

mostly excluding data showing increases or stability in insect

population, with the studies limited to specific geographic areas and

specific groups of species.

Claims of pending mass insect extinctions or "insect apocalypse" based

on a subset of these studies have been popularized in news reports, but

often extrapolate beyond the study data or hyperbolize study findings.

For some insect groups such as some butterflies, bees, and beetles,

declines in abundance and diversity have been documented in European

studies. Other areas have shown increases in some insect species,

although trends in most regions are currently unknown. It is difficult

to assess long-term trends in insect abundance or diversity because

historical measurements are generally not known for many species. Robust

data to assess at-risk areas or species is especially lacking for

arctic and tropical regions and a majority of the southern hemisphere.

| Order | Estimated total species |

|---|---|

| Archaeognatha | 513 |

| Zygentoma | 560 |

| Ephemeroptera | 3,240 |

| Odonata | 5,899 |

| Orthoptera | 23,855 |

| Neuroptera | 5,868 |

| Phasmatodea | 3,014 |

| Embioptera | 463 |

| Grylloblattodea | 34 |

| Mantophasmatodea | 20 |

| Plecoptera | 3,743 |

| Dermaptera | 1,978 |

| Zoraptera | 37 |

| Mantodea | 2,400 |

| Blattodea | 7,314 |

| Psocoptera | 5,720 |

| Phthiraptera | 5,102 |

| Thysanoptera | 5,864 |

| Hemiptera | 103,590 |

| Hymenoptera | 116,861 |

| Strepsiptera | 609 |

| Coleoptera | 386,500 |

| Megaloptera | 354 |

| Raphidioptera | 254 |

| Trichoptera | 14,391 |

| Lepidoptera | 157,338 |

| Diptera | 155,477 |

| Siphonaptera | 2,075 |

| Mecoptera | 757 |

Morphology and physiology

External

Insect morphology

A- Head B- Thorax C- Abdomen

A- Head B- Thorax C- Abdomen

1. antenna

2. ocelli (lower)

3. ocelli (upper)

4. compound eye

5. brain (cerebral ganglia)

6. prothorax

7. dorsal blood vessel

8. tracheal tubes (trunk with spiracle)

9. mesothorax

10. metathorax

11. forewing

12. hindwing

13. mid-gut (stomach)

14. dorsal tube (Heart)

15. ovary

16. hind-gut (intestine, rectum & anus)

17. anus

18. oviduct

19. nerve chord (abdominal ganglia)

20. Malpighian tubes

21. tarsal pads

22. claws

23. tarsus

24. tibia

25. femur

26. trochanter

27. fore-gut (crop, gizzard)

28. thoracic ganglion

29. coxa

30. salivary gland

31. subesophageal ganglion

32. mouthparts

2. ocelli (lower)

3. ocelli (upper)

4. compound eye

5. brain (cerebral ganglia)

6. prothorax

7. dorsal blood vessel

8. tracheal tubes (trunk with spiracle)

9. mesothorax

10. metathorax

11. forewing

12. hindwing

13. mid-gut (stomach)

14. dorsal tube (Heart)

15. ovary

16. hind-gut (intestine, rectum & anus)

17. anus

18. oviduct

19. nerve chord (abdominal ganglia)

20. Malpighian tubes

21. tarsal pads

22. claws

23. tarsus

24. tibia

25. femur

26. trochanter

27. fore-gut (crop, gizzard)

28. thoracic ganglion

29. coxa

30. salivary gland

31. subesophageal ganglion

32. mouthparts

Insects have segmented bodies supported by exoskeletons, the hard outer covering made mostly of chitin. The segments of the body are organized into three distinctive but interconnected units, or tagmata: a head, a thorax and an abdomen. The head supports a pair of sensory antennae, a pair of compound eyes, zero to three simple eyes (or ocelli) and three sets of variously modified appendages that form the mouthparts.

The thorax is made up of three segments: the prothorax, mesothorax and

the metathorax. Each thoracic segment supports one pair of legs. The

meso- and metathoracic segments may each have a pair of wings,

depending on the insect. The abdomen consists of eleven segments,

though in a few species of insects, these segments may be fused together

or reduced in size. The abdomen also contains most of the digestive, respiratory, excretory and reproductive internal structures. Considerable variation and many adaptations in the body parts of insects occur, especially wings, legs, antenna and mouthparts.

Segmentation

The head is enclosed in a hard, heavily sclerotized, unsegmented, exoskeletal head capsule, or epicranium,

which contains most of the sensing organs, including the antennae,

ocellus or eyes, and the mouthparts. Of all the insect orders,

Orthoptera displays the most features found in other insects, including

the sutures and sclerites. Here, the vertex, or the apex (dorsal region), is situated between the compound eyes for insects with a hypognathous and opisthognathous head. In prognathous insects, the vertex is not found between the compound eyes, but rather, where the ocelli

are normally. This is because the primary axis of the head is rotated

90° to become parallel to the primary axis of the body. In some species,

this region is modified and assumes a different name.

The thorax is a tagma composed of three sections, the prothorax, mesothorax and the metathorax.

The anterior segment, closest to the head, is the prothorax, with the

major features being the first pair of legs and the pronotum. The middle

segment is the mesothorax, with the major features being the second

pair of legs and the anterior wings. The third and most posterior

segment, abutting the abdomen, is the metathorax, which features the

third pair of legs and the posterior wings. Each segment is dilineated

by an intersegmental suture. Each segment has four basic regions. The

dorsal surface is called the tergum (or notum) to distinguish it from the abdominal terga.

The two lateral regions are called the pleura (singular: pleuron) and

the ventral aspect is called the sternum. In turn, the notum of the

prothorax is called the pronotum, the notum for the mesothorax is called

the mesonotum and the notum for the metathorax is called the metanotum.

Continuing with this logic, the mesopleura and metapleura, as well as

the mesosternum and metasternum, are used.

The abdomen

is the largest tagma of the insect, which typically consists of 11–12

segments and is less strongly sclerotized than the head or thorax. Each

segment of the abdomen is represented by a sclerotized tergum and

sternum. Terga are separated from each other and from the adjacent

sterna or pleura by membranes. Spiracles are located in the pleural

area. Variation of this ground plan includes the fusion of terga or

terga and sterna to form continuous dorsal or ventral shields or a

conical tube. Some insects bear a sclerite in the pleural area called a

laterotergite. Ventral sclerites are sometimes called laterosternites.

During the embryonic stage of many insects and the postembryonic stage

of primitive insects, 11 abdominal segments are present. In modern

insects there is a tendency toward reduction in the number of the

abdominal segments, but the primitive number of 11 is maintained during

embryogenesis. Variation in abdominal segment number is considerable. If

the Apterygota are considered to be indicative of the ground plan for

pterygotes, confusion reigns: adult Protura have 12 segments, Collembola

have 6. The orthopteran family Acrididae has 11 segments, and a fossil

specimen of Zoraptera has a 10-segmented abdomen.

Exoskeleton

The insect outer skeleton, the cuticle, is made up of two layers: the epicuticle, which is a thin and waxy water resistant outer layer and contains no chitin, and a lower layer called the procuticle.

The procuticle is chitinous and much thicker than the epicuticle and

has two layers: an outer layer known as the exocuticle and an inner

layer known as the endocuticle. The tough and flexible endocuticle is

built from numerous layers of fibrous chitin and proteins,

criss-crossing each other in a sandwich pattern, while the exocuticle is

rigid and hardened. The exocuticle is greatly reduced in many insects during their larval stages, e.g., caterpillars. It is also reduced in soft-bodied adult insects.

Insects are the only invertebrates to have developed active flight capability, and this has played an important role in their success.

Their flight muscles are able to contract multiple times for each

single nerve impulse, allowing the wings to beat faster than would

ordinarily be possible.

Having their muscles attached to their exoskeletons is efficient and allows more muscle connections.

Internal

Nervous system

The nervous system of an insect can be divided into a brain and a ventral nerve cord. The head capsule is made up of six fused segments, each with either a pair of ganglia,

or a cluster of nerve cells outside of the brain. The first three pairs

of ganglia are fused into the brain, while the three following pairs

are fused into a structure of three pairs of ganglia under the insect's esophagus, called the subesophageal ganglion.

The thoracic

segments have one ganglion on each side, which are connected into a

pair, one pair per segment. This arrangement is also seen in the abdomen

but only in the first eight segments. Many species of insects have

reduced numbers of ganglia due to fusion or reduction. Some cockroaches have just six ganglia in the abdomen, whereas the wasp Vespa crabro has only two in the thorax and three in the abdomen. Some insects, like the house fly Musca domestica, have all the body ganglia fused into a single large thoracic ganglion.

At least a few insects have nociceptors, cells that detect and transmit signals responsible for the sensation of pain. This was discovered in 2003 by studying the variation in reactions of larvae of the common fruitfly Drosophila

to the touch of a heated probe and an unheated one. The larvae reacted

to the touch of the heated probe with a stereotypical rolling behavior

that was not exhibited when the larvae were touched by the unheated

probe. Although nociception has been demonstrated in insects, there is no consensus that insects feel pain consciously.

Insects are capable of learning.

Digestive system

An insect uses its digestive system to extract nutrients and other substances from the food it consumes. Most of this food is ingested in the form of macromolecules and other complex substances like proteins, polysaccharides, fats and nucleic acids. These macromolecules must be broken down by catabolic reactions into smaller molecules like amino acids and simple sugars before being used by cells of the body for energy, growth, or reproduction. This break-down process is known as digestion.

There is extensive variation among different orders, life stages, and even castes in the digestive system of insects.

This is the result of extreme adaptations to various lifestyles. The

present description focus on a generalized composition of the digestive

system of an adult orthopteroid insect, which is considered basal to

interpreting particularities of other groups.

The main structure of an insect's digestive system is a long enclosed tube called the alimentary canal, which runs lengthwise through the body. The alimentary canal directs food unidirectionally from the mouth to the anus.

It has three sections, each of which performs a different process of

digestion. In addition to the alimentary canal, insects also have paired

salivary glands and salivary reservoirs. These structures usually

reside in the thorax, adjacent to the foregut. The salivary glands

(element 30 in numbered diagram) in an insect's mouth produce saliva.

The salivary ducts lead from the glands to the reservoirs and then

forward through the head to an opening called the salivarium, located

behind the hypopharynx. By moving its mouthparts (element 32 in numbered

diagram) the insect can mix its food with saliva. The mixture of saliva

and food then travels through the salivary tubes into the mouth, where

it begins to break down. Some insects, like flies, have extra-oral digestion.

Insects using extra-oral digestion expel digestive enzymes onto their

food to break it down. This strategy allows insects to extract a

significant proportion of the available nutrients from the food source. The gut is where almost all of insects' digestion takes place. It can be divided into the foregut, midgut and hindgut.

Foregut

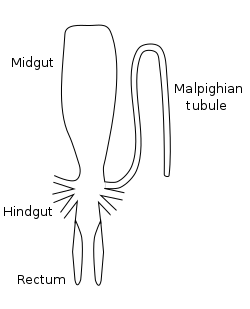

Stylized diagram of insect digestive tract showing malpighian tubule, from an insect of the order Orthoptera

The first section of the alimentary canal is the foregut (element 27 in numbered diagram), or stomodaeum. The foregut is lined with a cuticular lining made of chitin and proteins as protection from tough food. The foregut includes the buccal cavity (mouth), pharynx, esophagus and crop and proventriculus (any part may be highly modified), which both store food and signify when to continue passing onward to the midgut.

Digestion starts in buccal cavity (mouth) as partially chewed food is broken down by saliva from the salivary glands. As the salivary glands produce fluid and carbohydrate-digesting enzymes (mostly amylases),

strong muscles in the pharynx pump fluid into the buccal cavity,

lubricating the food like the salivarium does, and helping blood

feeders, and xylem and phloem feeders.

From there, the pharynx passes food to the esophagus, which could

be just a simple tube passing it on to the crop and proventriculus, and

then onward to the midgut, as in most insects. Alternately, the foregut

may expand into a very enlarged crop and proventriculus, or the crop

could just be a diverticulum, or fluid-filled structure, as in some Diptera species.

Midgut

Once food leaves the crop, it passes to the midgut

(element 13 in numbered diagram), also known as the mesenteron, where

the majority of digestion takes place. Microscopic projections from the

midgut wall, called microvilli,

increase the surface area of the wall and allow more nutrients to be

absorbed; they tend to be close to the origin of the midgut. In some

insects, the role of the microvilli and where they are located may vary.

For example, specialized microvilli producing digestive enzymes may

more likely be near the end of the midgut, and absorption near the

origin or beginning of the midgut.

Hindgut

In the hindgut (element 16 in numbered diagram), or proctodaeum, undigested food particles are joined by uric acid

to form fecal pellets. The rectum absorbs 90% of the water in these

fecal pellets, and the dry pellet is then eliminated through the anus

(element 17), completing the process of digestion. Envaginations at the

anterior end of the hindgut form the Malpighian tubules, which form the

main excretory system of insects.

Excretory system

Insects may have one to hundreds of Malpighian tubules

(element 20). These tubules remove nitrogenous wastes from the

hemolymph of the insect and regulate osmotic balance. Wastes and solutes

are emptied directly into the alimentary canal, at the junction between

the midgut and hindgut.[34]:71–72, 78–80

Reproductive system

The reproductive system of female insects consist of a pair of ovaries, accessory glands, one or more spermathecae, and ducts connecting these parts. The ovaries are made up of a number of egg tubes, called ovarioles,

which vary in size and number by species. The number of eggs that the

insect is able to make vary by the number of ovarioles with the rate

that eggs can develop being also influenced by ovariole design. Female

insects are able make eggs, receive and store sperm, manipulate sperm

from different males, and lay eggs. Accessory glands or glandular parts

of the oviducts produce a variety of substances for sperm maintenance,

transport and fertilization, as well as for protection of eggs. They can

produce glue and protective substances for coating eggs or tough

coverings for a batch of eggs called oothecae. Spermathecae are tubes or sacs in which sperm can be stored between the time of mating and the time an egg is fertilized.

For males, the reproductive system is the testis, suspended in the body cavity by tracheae and the fat body.

Most male insects have a pair of testes, inside of which are sperm

tubes or follicles that are enclosed within a membranous sac. The

follicles connect to the vas deferens by the vas efferens, and the two

tubular vasa deferentia connect to a median ejaculatory duct that leads

to the outside. A portion of the vas deferens is often enlarged to form

the seminal vesicle, which stores the sperm before they are discharged

into the female. The seminal vesicles have glandular linings that

secrete nutrients for nourishment and maintenance of the sperm. The

ejaculatory duct is derived from an invagination of the epidermal cells

during development and, as a result, has a cuticular lining. The

terminal portion of the ejaculatory duct may be sclerotized to form the

intromittent organ, the aedeagus. The remainder of the male reproductive

system is derived from embryonic mesoderm, except for the germ cells,

or spermatogonia, which descend from the primordial pole cells very early during embryogenesis.

Respiratory system

The tube-like heart (green) of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae extends horizontally across the body, interlinked with the diamond-shaped wing muscles (also green) and surrounded by pericardial cells (red). Blue depicts cell nuclei.

Insect respiration is accomplished without lungs. Instead, the insect respiratory system

uses a system of internal tubes and sacs through which gases either

diffuse or are actively pumped, delivering oxygen directly to tissues

that need it via their trachea

(element 8 in numbered diagram). In most insects, air is taken in

through openings on the sides of the abdomen and thorax called spiracles.

The respiratory system is an important factor that limits the

size of insects. As insects get larger, this type of oxygen transport is

less efficient and thus the heaviest insect currently weighs less than

100 g. However, with increased atmospheric oxygen levels, as were

present in the late Paleozoic, larger insects were possible, such as dragonflies with wingspans of more than two feet.

There are many different patterns of gas exchange demonstrated by different groups of insects. Gas exchange patterns in insects can range from continuous and diffusive ventilation, to discontinuous gas exchange. During continuous gas exchange, oxygen is taken in and carbon dioxide

is released in a continuous cycle. In discontinuous gas exchange,

however, the insect takes in oxygen while it is active and small amounts

of carbon dioxide are released when the insect is at rest. Diffusive ventilation is simply a form of continuous gas exchange that occurs by diffusion

rather than physically taking in the oxygen. Some species of insect

that are submerged also have adaptations to aid in respiration. As

larvae, many insects have gills that can extract oxygen dissolved in

water, while others need to rise to the water surface to replenish air

supplies, which may be held or trapped in special structures.

Circulatory system

Because oxygen is delivered directly to tissues via tracheoles, the

circulatory system is not used to carry oxygen, and is therefore greatly

reduced. The insect circulatory system is open; it has no veins or arteries, and instead consists of little more than a single, perforated dorsal tube that pulses peristaltically.

This dorsal blood vessel (element 14) is divided into two sections: the

heart and aorta. The dorsal blood vessel circulates the hemolymph, arthropods' fluid analog of blood, from the rear of the body cavity forward. Hemolymph is composed of plasma in which hemocytes

are suspended. Nutrients, hormones, wastes, and other substances are

transported throughout the insect body in the hemolymph. Hemocytes

include many types of cells that are important for immune responses,

wound healing, and other functions. Hemolymph pressure may be increased

by muscle contractions or by swallowing air into the digestive system to

aid in moulting. Hemolymph is also a major part of the open circulatory system of other arthropods, such as spiders and crustaceans.

Reproduction and development

A pair of grasshoppers mating.

The majority of insects hatch from eggs. The fertilization and development takes place inside the egg, enclosed by a shell (chorion)

that consists of maternal tissue. In contrast to eggs of other

arthropods, most insect eggs are drought resistant. This is because

inside the chorion two additional membranes develop from embryonic

tissue, the amnion and the serosa. This serosa secretes a cuticle rich in chitin that protects the embryo against desiccation. In Schizophora however the serosa does not develop, but these flies lay their eggs in damp places, such as rotting matter. Some species of insects, like the cockroach Blaptica dubia, as well as juvenile aphids and tsetse flies, are ovoviviparous. The eggs of ovoviviparous animals develop entirely inside the female, and then hatch immediately upon being laid. Some other species, such as those in the genus of cockroaches known as Diploptera, are viviparous, and thus gestate inside the mother and are born alive. Some insects, like parasitic wasps, show polyembryony, where a single fertilized egg divides into many and in some cases thousands of separate embryos. Insects may be univoltine, bivoltine or multivoltine, i.e. they may have one, two or many broods (generations) in a year.

The different forms of the male (top) and female (bottom) tussock moth Orgyia recens is an example of sexual dimorphism in insects.

Other developmental and reproductive variations include haplodiploidy, polymorphism, paedomorphosis or peramorphosis, sexual dimorphism, parthenogenesis and more rarely hermaphroditism. In haplodiploidy, which is a type of sex-determination system, the offspring's sex is determined by the number of sets of chromosomes an individual receives. This system is typical in bees and wasps. Polymorphism is where a species may have different morphs or forms, as in the oblong winged katydid, which has four different varieties: green, pink and yellow or tan. Some insects may retain phenotypes

that are normally only seen in juveniles; this is called

paedomorphosis. In peramorphosis, an opposite sort of phenomenon,

insects take on previously unseen traits after they have matured into

adults. Many insects display sexual dimorphism, in which males and

females have notably different appearances, such as the moth Orgyia recens as an exemplar of sexual dimorphism in insects.

Some insects use parthenogenesis, a process in which the female can reproduce and give birth without having the eggs fertilized by a male.

Many aphids undergo a form of parthenogenesis, called cyclical

parthenogenesis, in which they alternate between one or many generations

of asexual and sexual reproduction.

In summer, aphids are generally female and parthenogenetic; in the

autumn, males may be produced for sexual reproduction. Other insects

produced by parthenogenesis are bees, wasps and ants, in which they

spawn males. However, overall, most individuals are female, which are

produced by fertilization. The males are haploid and the females are diploid. More rarely, some insects display hermaphroditism, in which a given individual has both male and female reproductive organs.

Insect life-histories show adaptations to withstand cold and dry

conditions. Some temperate region insects are capable of activity during

winter, while some others migrate to a warmer climate or go into a

state of torpor. Still other insects have evolved mechanisms of diapause that allow eggs or pupae to survive these conditions.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis

in insects is the biological process of development all insects must

undergo. There are two forms of metamorphosis: incomplete metamorphosis

and complete metamorphosis.

Incomplete metamorphosis

Hemimetabolous insects, those with incomplete metamorphosis, change gradually by undergoing a series of molts.

An insect molts when it outgrows its exoskeleton, which does not

stretch and would otherwise restrict the insect's growth. The molting

process begins as the insect's epidermis secretes a new epicuticle

inside the old one. After this new epicuticle is secreted, the

epidermis releases a mixture of enzymes that digests the endocuticle and

thus detaches the old cuticle. When this stage is complete, the insect

makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air,

which makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where the

old exocuticle was thinnest.

Immature insects that go through incomplete metamorphosis are called nymphs or in the case of dragonflies and damselflies, also naiads.

Nymphs are similar in form to the adult except for the presence of

wings, which are not developed until adulthood. With each molt, nymphs

grow larger and become more similar in appearance to adult insects.

Complete metamorphosis

Gulf fritillary life cycle, an example of holometabolism.

Holometabolism, or complete metamorphosis, is where the insect changes in four stages, an egg or embryo, a larva, a pupa and the adult or imago. In these species, an egg hatches to produce a larva,

which is generally worm-like in form. This worm-like form can be one of

several varieties: eruciform (caterpillar-like), scarabaeiform

(grub-like), campodeiform (elongated, flattened and active), elateriform

(wireworm-like) or vermiform (maggot-like). The larva grows and

eventually becomes a pupa, a stage marked by reduced movement and often sealed within a cocoon.

There are three types of pupae: obtect, exarate or coarctate. Obtect

pupae are compact, with the legs and other appendages enclosed. Exarate

pupae have their legs and other appendages free and extended. Coarctate

pupae develop inside the larval skin.

Insects undergo considerable change in form during the pupal stage, and

emerge as adults. Butterflies are a well-known example of insects that

undergo complete metamorphosis, although most insects use this life

cycle. Some insects have evolved this system to hypermetamorphosis.

Complete metamorphosis is a trait of the most diverse insect group, the Endopterygota. Endopterygota includes 11 Orders, the largest being Diptera (flies), Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), and Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants), and Coleoptera (beetles). This form of development is exclusive to insects and not seen in any other arthropods.

Senses and communication

Many insects possess very sensitive and specialized organs of perception. Some insects such as bees can perceive ultraviolet wavelengths, or detect polarized light, while the antennae of male moths can detect the pheromones of female moths over distances of many kilometers. The yellow paper wasp (Polistes versicolor)

is known for its wagging movements as a form of communication within

the colony; it can waggle with a frequency of 10.6±2.1 Hz (n=190). These

wagging movements can signal the arrival of new material into the nest

and aggression between workers can be used to stimulate others to

increase foraging expeditions.

There is a pronounced tendency for there to be a trade-off between

visual acuity and chemical or tactile acuity, such that most insects

with well-developed eyes have reduced or simple antennae, and vice

versa. There are a variety of different mechanisms by which insects

perceive sound; while the patterns are not universal, insects can

generally hear sound if they can produce it. Different insect species

can have varying hearing,

though most insects can hear only a narrow range of frequencies related

to the frequency of the sounds they can produce. Mosquitoes have been

found to hear up to 2 kHz, and some grasshoppers can hear up to 50 kHz.

Certain predatory and parasitic insects can detect the characteristic

sounds made by their prey or hosts, respectively. For instance, some

nocturnal moths can perceive the ultrasonic emissions of bats, which helps them avoid predation. Insects that feed on blood have special sensory structures that can detect infrared emissions, and use them to home in on their hosts.

Some insects display a rudimentary sense of numbers,

such as the solitary wasps that prey upon a single species. The mother

wasp lays her eggs in individual cells and provides each egg with a

number of live caterpillars on which the young feed when hatched. Some

species of wasp always provide five, others twelve, and others as high

as twenty-four caterpillars per cell. The number of caterpillars is

different among species, but always the same for each sex of larva. The

male solitary wasp in the genus Eumenes

is smaller than the female, so the mother of one species supplies him

with only five caterpillars; the larger female receives ten caterpillars

in her cell.

Light production and vision

Most insects have compound eyes and two antennae.

A few insects, such as members of the families Poduridae and Onychiuridae (Collembola), Mycetophilidae (Diptera) and the beetle families Lampyridae, Phengodidae, Elateridae and Staphylinidae are bioluminescent. The most familiar group are the fireflies,

beetles of the family Lampyridae. Some species are able to control this

light generation to produce flashes. The function varies with some

species using them to attract mates, while others use them to lure prey.

Cave dwelling larvae of Arachnocampa (Mycetophilidae, fungus gnats) glow to lure small flying insects into sticky strands of silk.

Some fireflies of the genus Photuris mimic the flashing of female Photinus species to attract males of that species, which are then captured and devoured. The colors of emitted light vary from dull blue (Orfelia fultoni, Mycetophilidae) to the familiar greens and the rare reds (Phrixothrix tiemanni, Phengodidae).

Most insects, except some species of cave crickets,

are able to perceive light and dark. Many species have acute vision

capable of detecting minute movements. The eyes may include simple eyes

or ocelli as well as compound eyes of varying sizes. Many species are able to detect light in the infrared, ultraviolet and the visible light wavelengths. Color vision has been demonstrated in many species and phylogenetic analysis suggests that UV-green-blue trichromacy existed from at least the Devonian period between 416 and 359 million years ago.

Sound production and hearing

Insects were the earliest organisms to produce and sense sounds.

Insects make sounds mostly by mechanical action of appendages. In grasshoppers and crickets, this is achieved by stridulation. Cicadas make the loudest sounds among the insects by producing and amplifying sounds with special modifications to their body to form tymbals and associated musculature. The African cicada Brevisana brevis has been measured at 106.7 decibels at a distance of 50 cm (20 in). Some insects, such as the Helicoverpa zea moths, hawk moths and Hedylid butterflies, can hear ultrasound and take evasive action when they sense that they have been detected by bats. Some moths produce ultrasonic clicks that were once thought to have a role in jamming bat echolocation. The ultrasonic clicks were subsequently found to be produced mostly by unpalatable moths to warn bats, just as warning colorations are used against predators that hunt by sight. Some otherwise palatable moths have evolved to mimic these calls.

More recently, the claim that some moths can jam bat sonar has been

revisited. Ultrasonic recording and high-speed infrared videography of

bat-moth interactions suggest the palatable tiger moth really does

defend against attacking big brown bats using ultrasonic clicks that jam

bat sonar.

Very low sounds are also produced in various species of Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Mantodea and Neuroptera.

These low sounds are simply the sounds made by the insect's movement.

Through microscopic stridulatory structures located on the insect's

muscles and joints, the normal sounds of the insect moving are amplified

and can be used to warn or communicate with other insects. Most

sound-making insects also have tympanal organs that can perceive airborne sounds. Some species in Hemiptera, such as the corixids (water boatmen), are known to communicate via underwater sounds. Most insects are also able to sense vibrations transmitted through surfaces.

Communication using surface-borne vibrational signals is more

widespread among insects because of size constraints in producing

air-borne sounds.

Insects cannot effectively produce low-frequency sounds, and

high-frequency sounds tend to disperse more in a dense environment (such

as foliage), so insects living in such environments communicate primarily using substrate-borne vibrations. The mechanisms of production of vibrational signals are just as diverse as those for producing sound in insects.

Some species use vibrations for communicating within members of

the same species, such as to attract mates as in the songs of the shield bug Nezara viridula. Vibrations can also be used to communicate between entirely different species; lycaenid (gossamer-winged butterfly) caterpillars, which are myrmecophilous (living in a mutualistic association with ants) communicate with ants in this way. The Madagascar hissing cockroach has the ability to press air through its spiracles to make a hissing noise as a sign of aggression; the death's-head hawkmoth

makes a squeaking noise by forcing air out of their pharynx when

agitated, which may also reduce aggressive worker honey bee behavior

when the two are in close proximity.

Chemical communication

Chemical communications in animals rely on a variety of aspects

including taste and smell. Chemoreception is the physiological response

of a sense organ (i.e. taste or smell) to a chemical stimulus where the

chemicals act as signals to regulate the state or activity of a cell. A

semiochemical is a message-carrying chemical that is meant to attract,

repel, and convey information. Types of semiochemicals include

pheromones and kairomones. One example is the butterfly Phengaris arion which uses chemical signals as a form of mimicry to aid in predation.

In addition to the use of sound for communication, a wide range of insects have evolved chemical means for communication. These chemicals, termed semiochemicals, are often derived from plant metabolites include those meant to attract, repel and provide other kinds of information. Pheromones, a type of semiochemical, are used for attracting mates of the opposite sex, for aggregating conspecific

individuals of both sexes, for deterring other individuals from

approaching, to mark a trail, and to trigger aggression in nearby

individuals. Allomones benefit their producer by the effect they have upon the receiver. Kairomones

benefit their receiver instead of their producer. Synomones benefit the

producer and the receiver. While some chemicals are targeted at

individuals of the same species, others are used for communication

across species. The use of scents is especially well known to have

developed in social insects.

Social behavior

A cathedral mound created by termites (Isoptera).

Social insects, such as termites, ants and many bees and wasps, are the most familiar species of eusocial animals.

They live together in large well-organized colonies that may be so

tightly integrated and genetically similar that the colonies of some

species are sometimes considered superorganisms. It is sometimes argued that the various species of honey bee

are the only invertebrates (and indeed one of the few non-human groups)

to have evolved a system of abstract symbolic communication where a

behavior is used to represent and convey specific information about something in the environment. In this communication system, called dance language,

the angle at which a bee dances represents a direction relative to the

sun, and the length of the dance represents the distance to be flown. Though perhaps not as advanced as honey bees, bumblebees also potentially have some social communication behaviors. Bombus terrestris,

for example, exhibit a faster learning curve for visiting unfamiliar,

yet rewarding flowers, when they can see a conspecific foraging on the

same species.

Only insects that live in nests or colonies demonstrate any true

capacity for fine-scale spatial orientation or homing. This can allow an

insect to return unerringly to a single hole a few millimeters in

diameter among thousands of apparently identical holes clustered

together, after a trip of up to several kilometers' distance. In a

phenomenon known as philopatry, insects that hibernate have shown the ability to recall a specific location up to a year after last viewing the area of interest. A few insects seasonally migrate large distances between different geographic regions (e.g., the overwintering areas of the monarch butterfly).

Care of young

The eusocial insects build nests, guard eggs, and provide food for offspring full-time (see Eusociality).

Most insects, however, lead short lives as adults, and rarely interact

with one another except to mate or compete for mates. A small number

exhibit some form of parental care,

where they will at least guard their eggs, and sometimes continue

guarding their offspring until adulthood, and possibly even feeding

them. Another simple form of parental care is to construct a nest (a

burrow or an actual construction, either of which may be simple or

complex), store provisions in it, and lay an egg upon those provisions.

The adult does not contact the growing offspring, but it nonetheless

does provide food. This sort of care is typical for most species of bees

and various types of wasps.

Locomotion

Flight

White-lined sphinx moth feeding in flight

Basic

motion of the insect wing in insect with an indirect flight mechanism

scheme of dorsoventral cut through a thorax segment with

a wings

b joints

c dorsoventral muscles

d longitudinal muscles.

a wings

b joints

c dorsoventral muscles

d longitudinal muscles.

Insects are the only group of invertebrates to have developed flight. The evolution of insect wings has been a subject of debate. Some entomologists suggest that the wings are from paranotal lobes, or extensions from the insect's exoskeleton called the nota, called the paranotal theory. Other theories are based on a pleural

origin. These theories include suggestions that wings originated from

modified gills, spiracular flaps or as from an appendage of the epicoxa.

The epicoxal theory suggests the insect wings are modified epicoxal exites, a modified appendage at the base of the legs or coxa. In the Carboniferous age, some of the Meganeura

dragonflies had as much as a 50 cm (20 in) wide wingspan. The

appearance of gigantic insects has been found to be consistent with high

atmospheric oxygen. The respiratory system of insects constrains their

size, however the high oxygen in the atmosphere allowed larger sizes. The largest flying insects today are much smaller and include several moth species such as the Atlas moth and the white witch (Thysania agrippina).

Insect flight has been a topic of great interest in aerodynamics

due partly to the inability of steady-state theories to explain the

lift generated by the tiny wings of insects. But insect wings are in

motion, with flapping and vibrations, resulting in churning and eddies, and the misconception that physics says "bumblebees can't fly" persisted throughout most of the twentieth century.

Unlike birds, many small insects are swept along by the prevailing winds although many of the larger insects are known to make migrations. Aphids are known to be transported long distances by low-level jet streams. As such, fine line patterns associated with converging winds within weather radar imagery, like the WSR-88D radar network, often represent large groups of insects.

Walking

Spatial

and temporal stepping pattern of walking desert ants performing an

alternating tripod gait. Recording rate: 500 fps, Playback rate: 10 fps.

Many adult insects use six legs for walking and have adopted a tripedal gait. The tripedal gait allows for rapid walking while always having a stable stance and has been studied extensively in cockroaches and ants.

The legs are used in alternate triangles touching the ground. For the

first step, the middle right leg and the front and rear left legs are in

contact with the ground and move the insect forward, while the front

and rear right leg and the middle left leg are lifted and moved forward

to a new position. When they touch the ground to form a new stable

triangle the other legs can be lifted and brought forward in turn and so

on.

The purest form of the tripedal gait is seen in insects moving at high

speeds. However, this type of locomotion is not rigid and insects can

adapt a variety of gaits. For example, when moving slowly, turning,

avoiding obstacles, climbing or slippery surfaces, four (tetrapod) or

more feet (wave-gait) may be touching the ground. Insects can also adapt their gait to cope with the loss of one or more limbs.

Cockroaches are among the fastest insect runners and, at full

speed, adopt a bipedal run to reach a high velocity in proportion to

their body size. As cockroaches move very quickly, they need to be video

recorded at several hundred frames per second to reveal their gait.

More sedate locomotion is seen in the stick insects or walking sticks (Phasmatodea). A few insects have evolved to walk on the surface of the water, especially members of the Gerridae family, commonly known as water striders. A few species of ocean-skaters in the genus Halobates even live on the surface of open oceans, a habitat that has few insect species.

Use in robotics

Insect walking is of particular interest as an alternative form of locomotion in robots. The study of insects and bipeds has a significant impact on possible robotic methods of transport. This may allow new robots to be designed that can traverse terrain that robots with wheels may be unable to handle.

Swimming

The backswimmer Notonecta glauca underwater, showing its paddle-like hindleg adaptation

A large number of insects live either part or the whole of their

lives underwater. In many of the more primitive orders of insect, the

immature stages are spent in an aquatic environment. Some groups of

insects, like certain water beetles, have aquatic adults as well.

Many of these species have adaptations to help in under-water

locomotion. Water beetles and water bugs have legs adapted into

paddle-like structures. Dragonfly naiads use jet propulsion, forcibly expelling water out of their rectal chamber. Some species like the water striders

are capable of walking on the surface of water. They can do this

because their claws are not at the tips of the legs as in most insects,

but recessed in a special groove further up the leg; this prevents the

claws from piercing the water's surface film. Other insects such as the Rove beetle Stenus

are known to emit pygidial gland secretions that reduce surface tension

making it possible for them to move on the surface of water by Marangoni propulsion (also known by the German term Entspannungsschwimmen).

Ecology

Insect ecology is the scientific study of how insects, individually or as a community, interact with the surrounding environment or ecosystem.

Insects play one of the most important roles in their ecosystems, which

includes many roles, such as soil turning and aeration, dung burial,

pest control, pollination and wildlife nutrition. An example is the beetles, which are scavengers that feed on dead animals and fallen trees and thereby recycle biological materials into forms found useful by other organisms. These insects, and others, are responsible for much of the process by which topsoil is created.

Defense and predation

Perhaps one of the most well-known examples of mimicry, the viceroy butterfly (top) appears very similar to the monarch butterfly (bottom).

Insects are mostly soft bodied, fragile and almost defenseless

compared to other, larger lifeforms. The immature stages are small, move

slowly or are immobile, and so all stages are exposed to predation and parasitism. Insects then have a variety of defense strategies to avoid being attacked by predators or parasitoids. These include camouflage, mimicry, toxicity and active defense.

Camouflage is an important defense strategy, which involves the use of coloration or shape to blend into the surrounding environment.

This sort of protective coloration is common and widespread among

beetle families, especially those that feed on wood or vegetation, such

as many of the leaf beetles (family Chrysomelidae) or weevils.

In some of these species, sculpturing or various colored scales or

hairs cause the beetle to resemble bird dung or other inedible objects.

Many of those that live in sandy environments blend in with the

coloration of the substrate. Most phasmids are known for effectively replicating the forms of sticks and leaves, and the bodies of some species (such as O. macklotti and Palophus centaurus) are covered in mossy or lichenous

outgrowths that supplement their disguise. Very rarely, a species may

have the ability to change color as their surroundings shift (Bostra scabrinota). In a further behavioral adaptation to supplement crypsis,

a number of species have been noted to perform a rocking motion where

the body is swayed from side to side that is thought to reflect the

movement of leaves or twigs swaying in the breeze. Another method by

which stick insects avoid predation and resemble twigs is by feigning

death (catalepsy),

where the insect enters a motionless state that can be maintained for a

long period. The nocturnal feeding habits of adults also aids

Phasmatodea in remaining concealed from predators.

Another defense that often uses color or shape to deceive potential enemies is mimicry. A number of longhorn beetles (family Cerambycidae) bear a striking resemblance to wasps, which helps them avoid predation even though the beetles are in fact harmless. Batesian and Müllerian mimicry

complexes are commonly found in Lepidoptera. Genetic polymorphism and

natural selection give rise to otherwise edible species (the mimic)

gaining a survival advantage by resembling inedible species (the model).

Such a mimicry complex is referred to as Batesian. One of the most famous examples, where the viceroy butterfly was long believed to be a Batesian mimic of the inedible monarch,

was later disproven, as the viceroy is more toxic than the monarch, and

this resemblance is now considered to be a case of Müllerian mimicry.

In Müllerian mimicry, inedible species, usually within a taxonomic

order, find it advantageous to resemble each other so as to reduce the

sampling rate by predators who need to learn about the insects'

inedibility. Taxa from the toxic genus Heliconius form one of the most well known Müllerian complexes.

Chemical defense is another important defense found among species

of Coleoptera and Lepidoptera, usually being advertised by bright

colors, such as the monarch butterfly.

They obtain their toxicity by sequestering the chemicals from the

plants they eat into their own tissues. Some Lepidoptera manufacture

their own toxins. Predators that eat poisonous butterflies and moths may

become sick and vomit violently, learning not to eat those types of

species; this is actually the basis of Müllerian mimicry. A predator who

has previously eaten a poisonous lepidopteran may avoid other species

with similar markings in the future, thus saving many other species as

well. Some ground beetles of the family Carabidae can spray chemicals from their abdomen with great accuracy, to repel predators.

Pollination

European honey bee carrying pollen in a pollen basket back to the hive

Pollination is the process by which pollen is transferred in the reproduction of plants, thereby enabling fertilisation and sexual reproduction.

Most flowering plants require an animal to do the transportation. While

other animals are included as pollinators, the majority of pollination

is done by insects. Because insects usually receive benefit for the pollination in the form of energy rich nectar it is a grand example of mutualism.

The various flower traits (and combinations thereof) that

differentially attract one type of pollinator or another are known as pollination syndromes.

These arose through complex plant-animal adaptations. Pollinators find

flowers through bright colorations, including ultraviolet, and

attractant pheromones. The study of pollination by insects is known as anthecology.

Parasitism

Many insects are parasites of other insects such as the parasitoid wasps. These insects are known as entomophagous parasites.

They can be beneficial due to their devastation of pests that can

destroy crops and other resources. Many insects have a parasitic

relationship with humans such as the mosquito. These insects are known

to spread diseases such as malaria and yellow fever and because of such, mosquitoes indirectly cause more deaths of humans than any other animal.

Relationship to humans

As pests

Many insects are considered pests by humans. Insects commonly regarded as pests include those that are parasitic (e.g. lice, bed bugs), transmit diseases (mosquitoes, flies), damage structures (termites), or destroy agricultural goods (locusts, weevils). Many entomologists are involved in various forms of pest control, as in research for companies to produce insecticides, but increasingly rely on methods of biological pest control,

or biocontrol. Biocontrol uses one organism to reduce the population

density of another organism—the pest—and is considered a key element of integrated pest management.

Despite the large amount of effort focused at controlling

insects, human attempts to kill pests with insecticides can backfire. If

used carelessly, the poison can kill all kinds of organisms in the

area, including insects' natural predators, such as birds, mice and

other insectivores. The effects of DDT's use exemplifies how some insecticides can threaten wildlife beyond intended populations of pest insects.

In beneficial roles

Because they help flowering plants to cross-pollinate, some insects are critical to agriculture. This European honey bee is gathering nectar while pollen collects on its body.

A robberfly with its prey, a hoverfly. Insectivorous relationships such as these help control insect populations.

Although pest insects attract the most attention, many insects are beneficial to the environment and to humans. Some insects, like wasps, bees, butterflies and ants, pollinate flowering plants. Pollination is a mutualistic relationship between plants and insects. As insects gather nectar from different plants of the same species, they also spread pollen from plants on which they have previously fed. This greatly increases plants' ability to cross-pollinate, which maintains and possibly even improves their evolutionary fitness. This ultimately affects humans since ensuring healthy crops is critical to agriculture.

As well as pollination ants help with seed distribution of plants. This

helps to spread the plants, which increases plant diversity. This leads

to an overall better environment. A serious environmental problem is the decline of populations of pollinator insects, and a number of species of insects are now cultured primarily for pollination management in order to have sufficient pollinators in the field, orchard or greenhouse at bloom time. Another solution, as shown in Delaware, has been to raise native plants to help support native pollinators like L. vierecki. Insects also produce useful substances such as honey, wax, lacquer and silk. Honey bees

have been cultured by humans for thousands of years for honey, although

contracting for crop pollination is becoming more significant for beekeepers. The silkworm has greatly affected human history, as silk-driven trade established relationships between China and the rest of the world.

Insectivorous

insects, or insects that feed on other insects, are beneficial to

humans if they eat insects that could cause damage to agriculture and

human structures. For example, aphids feed on crops and cause problems for farmers, but ladybugs feed on aphids, and can be used as a means to significantly reduce pest aphid populations. While birds

are perhaps more visible predators of insects, insects themselves

account for the vast majority of insect consumption. Ants also help

control animal populations by consuming small vertebrates. Without predators to keep them in check, insects can undergo almost unstoppable population explosions.

Insects are also used in medicine, for example fly larvae (maggots) were formerly used to treat wounds to prevent or stop gangrene,

as they would only consume dead flesh. This treatment is finding modern

usage in some hospitals. Recently insects have also gained attention as

potential sources of drugs and other medicinal substances. Adult insects, such as crickets and insect larvae of various kinds, are also commonly used as fishing bait.

In research

The common fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster is one of the most widely used organisms in biological research.

Insects play important roles in biological research. For example, because of its small size, short generation time and high fecundity, the common fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster is a model organism for studies in the genetics of higher eukaryotes. D. melanogaster has been an essential part of studies into principles like genetic linkage, interactions between genes, chromosomal genetics, development, behavior and evolution. Because genetic systems are well conserved among eukaryotes, understanding basic cellular processes like DNA replication or transcription in fruit flies can help to understand those processes in other eukaryotes, including humans. The genome of D. melanogaster was sequenced

in 2000, reflecting the organism's important role in biological

research. It was found that 70% of the fly genome is similar to the

human genome, supporting the evolution theory.

As food

In some cultures, insects, especially deep-fried cicadas, are considered to be delicacies,

whereas in other places they form part of the normal diet. Insects have

a high protein content for their mass, and some authors suggest their

potential as a major source of protein in human nutrition. In most first-world countries, however, entomophagy (the eating of insects), is taboo.

Since it is impossible to entirely eliminate pest insects from the human

food chain, insects are inadvertently present in many foods, especially

grains. Food safety laws in many countries do not prohibit insect parts in food, but rather limit their quantity. According to cultural materialist anthropologist Marvin Harris, the eating of insects is taboo in cultures that have other protein sources such as fish or livestock.

Due to the abundance of insects and a worldwide concern of food shortages, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

considers that the world may have to, in the future, regard the

prospects of eating insects as a food staple. Insects are noted for

their nutrients, having a high content of protein, minerals and fats and

are eaten by one-third of the global population.

As foddder

Processed maggots can be used as fodder for farmed animals such as chicken, fish and pigs.

In other products

Insect larvae (i.e. black soldier fly larvae) can provide protein, grease, and chitin. The grease is usable in the pharmaceutical industry (cosmetics, surfactants for shower gel) -hereby replacing other vegetable oils as palm oil.

As pets

Many species of insects are sold and kept as pets.

In culture

Scarab beetles held religious and cultural symbolism in Old Egypt, Greece and some shamanistic Old World cultures. The ancient Chinese regarded cicadas as symbols of rebirth or immortality. In Mesopotamian literature, the epic poem of Gilgamesh has allusions to Odonata that signify the impossibility of immortality. Among the Aborigines of Australia of the Arrernte language groups, honey ants and witchety grubs served as personal clan totems. In the case of the 'San' bush-men of the Kalahari, it is the praying mantis that holds much cultural significance including creation and zen-like patience in waiting.