Home to one of the Cradles of Civilization, the Middle East—interchangeable with the Near East—has seen many of the world's oldest cultures and civilizations. This history started from the earliest human settlements, continuing through several major pre- and post-Islamic Empires through to the nation-states of the Middle East today.

Sumerians were the first people to develop complex systems as to be called "Civilization", starting as far back as the 5th millennium BC. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh. Mesopotamia was home to several powerful empires that came to rule almost the entire Middle East—particularly the Assyrian Empires of 1365–1076 BC and the Neo-Assyrian Empire of 911–609 BC. From the early 7th century BC and onward, the Iranian Medes followed by the Achaemenid Empire and other subsequent Iranian states and empires dominated the region. In the 1st century BC, the expanding Roman Republic absorbed the whole Eastern Mediterranean, which included much of the Near East. The Eastern Roman Empire, today commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, ruling from the Balkans to the Euphrates, became increasingly defined by and dogmatic about Christianity, gradually creating religious rifts between the doctrines dictated by the establishment in Constantinople and believers in many parts of the Middle East. From the 3rd century up to the course of the 7th century AD, the entire Middle East was dominated by the Byzantines and the Sasanian Empire. From the 7th century, a new power was rising in the Middle East, that of Islam. The dominance of the Arabs came to a sudden end in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuq dynasty. In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the armies of the Mongol Empire, mainly Turkic, swept through the region. By the early 15th century, a new power had arisen in western Anatolia, the Ottoman emirs, linguistically Turkic and religiously Islamic, who in 1453 captured the Christian Byzantine capital of Constantinople and made themselves sultans.

Large parts of the Middle East became a warground between the Ottomans and the Iranian Safavid dynasty for centuries, starting in the early 16th century. By 1700, the Ottomans had been driven out of the Kingdom of Hungary and the balance of power along the frontier had shifted decisively in favor of the Western world. The British Empire also established effective control of the Persian Gulf, and the French colonial empire extended its influence into Lebanon and Syria. In 1912, the Kingdom of Italy seized Libya and the Dodecanese islands, just off the coast of the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Middle Eastern rulers tried to modernize their states to compete more effectively with the European powers. A turning point in the history of the Middle East came when oil was discovered, first in Persia in 1908 and later in Saudi Arabia (in 1938) and the other Persian Gulf states, and also in Libya and Algeria. A Western dependence on Middle Eastern oil and the decline of British influence led to a growing American interest in the region.

During the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Syria and Egypt made moves towards independence. The British, the French, and the Soviet Union departed from many parts of the Middle East during and after World War II (1939–1945). The Arab–Israeli conflict in Palestine culminated in the 1947 United Nations plan to partition Palestine. Later in the midst of Cold War tensions, the Arabic-speaking countries of Western Asia and Northern Africa saw the rise of pan-Arabism. The departure of the European powers from direct control of the region, the establishment of Israel, and the increasing importance of the petroleum industry, marked the creation of the modern Middle East. In most Middle Eastern countries, the growth of market economies was inhibited by political restrictions, corruption and cronyism, overspending on arms and prestige projects, and over-dependence on oil revenues. The wealthiest economies in the region per capita are the small oil-rich countries of Persian Gulf: Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates.

A combination of factors—among them the 1967 Six-Day War, the 1970s energy crisis beginning with the 1973 OPEC oil embargo in response to U.S. support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, the concurrent Saudi-led popularization of Salafism/Wahhabism, and the 1978-79 Iranian Revolution—promoted the increasing rise of Islamism and the ongoing Islamic revival (Tajdid). The Fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought a global security refocus from the Cold War to a War on Terror. Starting in the early 2010s, a revolutionary wave popularly known as the Arab Spring brought major protests, uprisings, and revolutions to several Middle Eastern and Maghreb countries. Clashes in western Iraq on 30 December 2013 were preliminary to the Sunni pan-Islamist ISIL uprising.

The term Near East can be used interchangeably with Middle East, but in a different context, especially when discussing ancient history, it may have a limited meaning, namely the northern, historically Aramaic-speaking Semitic people area and adjacent Anatolian territories, marked in the two maps below.

General

Geographically, the Middle East can be thought of as Western Asia with the addition of Egypt (which is the non-Maghreb region of Northern Africa) and with the exclusion of the Caucasus. The Middle East was the first to experience a Neolithic Revolution (c. the 10th millennium BCE), as well as the first to enter the Bronze Age (c. 3300–1200 BC) and Iron Age (c. 1200–500 BC).

Historically human populations have tended to settle around bodies of water, which is reflected in modern population density patterns. Irrigation systems were extremely important for the agricultural Middle East: for Egypt that of the lower Nile River, and for Mesopotamia that of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Levantine agriculture depended on precipitation rather than on the river-based irrigation of Egypt and Mesopotamia, resulting in preference for different crops. Since travel was faster and easier by sea, civilizations along the Mediterranean, such as Phoenicia and later Greece, participated in intense trade. Similarly, Ancient Yemen, much more conducive to agriculture than the rest of the Arabian Peninsula, sea traded heavily with the Horn of Africa, some of which it lingually Semitized. The Adnanite Arabs, inhabiting the drier desert areas of the Middle East, were all nomadic pastoralists before some began settling in city states, with the geo-linguistic distribution today being divided between Persian Gulf, the Najd and the Hejaz in the Peninsula, as well as the Bedouin areas beyond the Peninsula.

Since ancient times the Middle East has had several lingua franca: Akkadian (c. 14th–8th century BC), Aramaic (c. 8th century BC – 8th century AD), Greek (c. 4th century BC – 8th century AD), and Arabic (c. 8th century AD – present). Familiarity with English is not uncommon among the middle and upper classes. Arabic is not commonly spoken in Turkey, Iran, and Israel, and some varieties of Arabic lack mutual intelligibility, thus qualifying as distinct languages by this linguistic criterion.

The Middle East was the birthplace of the Abrahamic, Gnostic, and most Iranian religions. Initially the ancient inhabitants of the region followed various ethnic religions, but most of those began to be gradually replaced at first by Christianity (even before the 313 AD Edict of Milan) and finally by Islam (after the spread of the Muslim conquests beyond the Arabian Peninsula in 634 AD). To this day, however, the Middle East has, in particular, some sizable, ethnically distinct Christian minority groups, as well as Jews, concentrated in Israel, and followers of Iranian religions, such as Yazdânism and Zoroastrianism. Some of the smaller ethnoreligious minorities include the Shabak people, the Mandaeans and the Samaritans. It is somewhat controversial whether the Druze religion is a distinct religion in its own right or merely a part of the Ismailist branch of Shia Islam.

Prehistoric Near East

The Arabian Tectonic Plate was part of the African Plate during much of the Phanerozoic Eon (Paleozoic–Cenozoic), until the Oligocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era. Red Sea rifting began in the Eocene, but the separation of Africa and Arabia occurred in the Oligocene, and since then the Arabian Plate has been slowly moving toward the Eurasian Plate.

The collision between the Arabian Plate and Eurasia is pushing up the Zagros Mountains of Iran. Because the Arabian Plate and Eurasia plate collide, many cities are in danger such as those in south eastern Turkey (which is on the Arabian Plate). These dangers include earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes.

The earliest human migrations out of Africa occurred through the Middle East, namely over the Levantine corridor, with the pre-modern Homo erectus about 1.8 million years BP. One of the potential routes for early human migrations toward southern and eastern Asia is Iran.

Haplogroup J-P209, the most common human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup in the Middle East today, is believed to have arisen in the region 31,700±12,800 years ago. The two main current subgroups, J-M267 and J-M172, which now comprise between them almost all of the population of the haplogroup, are both believed to have arisen very early, at least 10,000 years ago. Nonetheless, Y-chromosomes F-M89* and IJ-M429* were reported to have been observed in the Iranian plateau.

There is evidence of rock carvings along the Nile terraces and in desert oases. In the 10th millennium BC, a culture of hunter-gatherers and fishermen was replaced by a grain-grinding culture. Climate changes and/or overgrazing around 6000 BC began to desiccate the pastoral lands of Egypt, forming the Sahara. Early tribal peoples migrated to the Nile River, where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralized society.

Neolithic agriculturalists, who may have resided in Northeast Africa and the Near East, may have been the source population for lactase persistence variants, including –13910*T, and may have been subsequently supplanted by later migrations of peoples. The Sub-Saharan West African Fulani, the North African Tuareg, and European agriculturalists, who are descendants of these Neolithic agriculturalists, share the lactase persistence variant –13910*T. While shared by Fulani and Tuareg herders, compared to the Tuareg variant, the Fulani variant of –13910*T has undergone a longer period of haplotype differentiation. The Fulani lactase persistence variant –13910*T may have spread, along with cattle pastoralism, between 9686 BP and 7534 BP, possibly around 8500 BP; corroborating this timeframe for the Fulani, by at least 7500 BP, there is evidence of herders engaging in the act of milking in the Central Sahara.

Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the first to practice intensive year-round agriculture and currency-mediated trade (as opposed to barter), gave the rest of the world the first writing system, invented the potter's wheel and then the vehicular and mill wheel, created the first centralized governments and law codes, served as birthplace to the first city-states with their high degree of division of labor, as well as laying the foundation for the fields of astronomy and mathematics. However, its empires also introduced rigid social stratification, slavery, and organized warfare.

Cradle of civilization, Sumer and Akkad

The earliest civilizations in history were established in the region now known as the Middle East around 3500 BC by the Sumerians, in Mesopotamia (Iraq), widely regarded as the cradle of civilization. The Sumerians and the Akkadians, and later Babylonians and Assyrians all flourished in this region.

"In the course of the fourth millennium BC, city-states developed in southern Mesopotamia that were dominated by temples whose priests represented the cities' patron deities. The most prominent of the city-states was Sumer, which gave its language to the area, [presumably the first written language,] and became the first great civilization of mankind. About 2340 BC, Sargon the Great (c. 2360–2305 BC) united the city-states in the south and founded the Akkadian dynasty, the world's first empire."

During this same time period, Sargon the Great appointed his daughter, Enheduanna, as High Priestess of Inanna at Ur. Her writings, which established her as the first known author in world history, also helped cement Sargon's position in the region.

Egypt

Soon after the Sumerian civilization began, the Nile valley of Lower and Upper Egypt was unified under the Pharaohs approximately around 3150 BC. Since then, Ancient Egypt experienced 3 high points of civilization, the so-called "Kingdom" periods:

- The Old Kingdom (2686–2181),

- The Middle Kingdom (2055–1650) and, most notably,

- The New Kingdom (1550–1069).

The history of Ancient Egypt is concluded by the Late Period (664–332 BC), immediately followed by the history of Egypt in Classical Antiquity, beginning with Ptolemaic Egypt.

The Levant and Anatolia

Thereafter, civilization quickly spread through the Fertile Crescent to the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea and throughout the Levant, as well as to ancient Anatolia. Ancient Levantine kingdoms and city states included Ebla City, Ugarit City, Kingdom of Aram-Damascus, Kingdom of Israel, Kingdom of Judah, Kingdom of Ammon, Kingdom of Moab, Kingdom of Edom, and the Nabatean kingdom. The Phoenician civilization, encompassing several city states, was a maritime trading culture that established colonial cities in the Mediterranean Basin, most notably Carthage, in 814 BC.

Assyrian empires

Mesopotamia was home to several powerful empires that came to rule almost the entire Middle East—particularly the Assyrian Empires of 1365–1076 BC and the Neo-Assyrian Empire of 911–605 BC. The Assyrian Empire, at its peak, was the largest the world had seen. It ruled all of what is now Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Kuwait, Jordan, Egypt, Cyprus, and Bahrain—with large swathes of Iran, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, Sudan, and Arabia. "The Assyrian empires, particularly the third, had a profound and lasting impact on the Near East. Before Assyrian hegemony ended, the Assyrians brought the highest civilization to the then known world. From the Caspian to Cyprus, from Anatolia to Egypt, Assyrian imperial expansion would bring into the Assyrian sphere nomadic and barbaric communities, and would bestow the gift of civilization upon them."

Neo-Babylonian and Persian empires

From the early 6th century BC onwards, several Persian states dominated the region, beginning with the Medes and non-Persian Neo-Babylonian Empire, then their successor the Achaemenid Empire known as the first Persian Empire, conquered in the late 4th century BC by the very short-lived Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great, and then successor kingdoms such as Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid state in Western Asia.

After a century of hiatus, the idea of the Persian Empire was revived by the Parthians in the 3rd century BC—and continued by their successors, the Sassanids from the 3rd century AD. This empire dominated sizable parts of what is now the Asian part of the Middle East and continued to influence the rest of the Asiatic and African Middle East region, until the Arab Muslim conquest of Persia in the mid-7th century AD. Between the 1st century BC and the early 7th century AD, the region was completely dominated by the Romans and the Parthians and Sassanids on the other hand, which often culminated in various Roman-Persian Wars over the seven centuries. Eastern Rite, Church of the East Christianity took hold in Persian-ruled Mesopotamia, particularly in Assyria from the 1st century AD onwards, and the region became a center of a flourishing Syriac–Assyrian literary tradition.

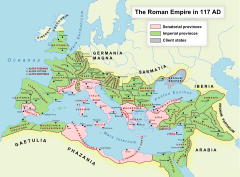

Greek and Roman Empire

In 66–63 BC, the Roman general Pompey conquered much of the Middle East. The Roman Empire united the region with most of Europe and North Africa in a single political and economic unit. Even areas not directly annexed were strongly influenced by the Empire, which was the most powerful political and cultural entity for centuries. Though Roman culture spread across the region, the Greek culture and language first established in the region by the Macedonian Empire continued to dominate throughout the Roman period. Cities in the Middle East, especially Alexandria, became major urban centers for the Empire and the region became the Empire's "bread basket" as the key agricultural producer. Ægyptus was by far the most wealthy Roman province.

As the Christian religion spread throughout the Roman and Persian Empires, it took root in the Middle East, and cities such as Alexandria and Edessa became important centers of Christian scholarship. By the 5th century, Christianity was the dominant religion in the Middle East, with other faiths (gradually including heretical Christian sects) being actively repressed. The Middle East's ties to the city of Rome were gradually severed as the Empire split into East and West, with the Middle East tied to the new Roman capital of Constantinople. The subsequent Fall of the Western Roman Empire therefore, had minimal direct impact on the region.

Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire)

The Eastern Roman Empire, today commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, ruling from the Balkans to the Euphrates, became increasingly defined by and dogmatic about Christianity, gradually creating religious rifts between the doctrines dictated by the establishment in Constantinople and believers in many parts of the Middle East. By this time, Greek had become the 'lingua franca' of the region, although ethnicities such as the Syriacs and the Hebrew continued to exist. Under Byzantine/Greek rule the area of the Levant met an era of stability and prosperity.

Medieval Middle East

Pre-Islam

In the 5th century, the Middle East was separated into small, weak states; the two most prominent were the Sasanian Empire of the Persians in what is now Iran and Iraq, and the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and the Levant. The Byzantines and Sasanians fought with each other a reflection of the rivalry between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire seen during the previous five hundred years. The Byzantine-Sasanian rivalry was also seen through their respective cultures and religions. The Byzantines considered themselves champions of Hellenism and Christianity. Meanwhile, the Sasanians thought themselves heroes of ancient Iranian traditions and of the traditional Persian religion, Zoroastrianism.

The Arabian peninsula already played a role in the power struggles of the Byzantines and Sasanians. While Byzantium allied itself with the Kingdom of Aksum in the horn of Africa, the Sasanian Empire assisted the Himyarite Kingdom in what is now Yemen (southwest Arabia). Thus the clash between the kingdoms of Aksum and Himyar in 525 displayed a higher power struggle between Byzantium and Persia for control of the Red Sea trade. Territorial wars soon became common, with the Byzantines and Sasanians fighting over upper Mesopotamia and Armenia and key cities that facilitated trade from Arabia, India, and China. Byzantium, as the continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire, continued control of the latter's territories in the Middle East. Since 527, this included Anatolia, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt. But in 603 the Sasanians invaded, conquering Damascus and Egypt. It was Emperor Heraclius who was able to repel these invasions, and in 628 he replaced the Sasanian Great King with a more docile one. But the fighting weakened both states, leaving the stage open to a new power.

The nomadic Bedouin tribes dominated the Arabian desert, where they worshiped idols and remained in small clans tied together by kinship. Urbanization and agriculture was limited in Arabia, save for a few regions near the coast. Mecca and Medina (then called Yathrib) were two such cities that were important hubs for trade between Africa and Eurasia. This commerce was central to city-life, where most inhabitants were merchants. Nevertheless, some Arabs saw it fit to migrate to the northern regions of the Fertile Crescent, a region so named for its place between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that offered it fertile land. This included entire tribal chiefdoms such as the Lakhmids in a less controlled area of the Sasanian Empire, and the Ghassanids in a similar area inside of Byzantine territory; these political units of Arab origin offered a surprising stability that was rare in the region and offered Arabia further connections to the outside world. The Lakhmid capital, Hira was a center for Christianity and Jewish craftsmen, merchants, and farmers were common in western Arabia as were Christian monks in central Arabia. Thus pre-Islamic Arabia was no stranger to Abrahamic religions or monotheism, for that matter.

Islamic caliphate

While the Byzantine Roman and Sassanid Persian empires were both weakened by warfare (602–628), a new power in the form of Islam grew in the Middle East. In a series of rapid Muslim conquests, Arab armies, led by the Caliphs and skilled military commanders such as Khalid ibn al-Walid, swept through most of the Middle East, taking more than half of Byzantine territory and completely engulfing the Persian lands. In Anatolia, they were stopped in the Siege of Constantinople (717–718) by the Byzantines, who were helped by the Bulgarians.

The Byzantine provinces of Roman Syria, North Africa, and Sicily, however, could not mount such a resistance, and the Muslim conquerors swept through those regions. At the far west, they crossed the sea taking Visigothic Hispania before being halted in southern France in the Battle of Tours by the Franks. At its greatest extent, the Arab Empire was the first empire to control the entire Middle East, as well three-quarters of the Mediterranean region, the only other empire besides the Roman Empire to control most of the Mediterranean Sea. It would be the Arab Caliphates of the Middle Ages that would first unify the entire Middle East as a distinct region and create the dominant ethnic identity that persists today. The Seljuq Empire would also later dominate the region.

Much of North Africa became a peripheral area to the main Muslim centres in the Middle East, but Iberia (Al-Andalus) and Morocco soon broke away from this distant control and founded one of the world's most advanced societies at the time, along with Baghdad in the eastern Mediterranean. Between 831 and 1071, the Emirate of Sicily was one of the major centres of Islamic culture in the Mediterranean. After its conquest by the Normans the island developed its own distinct culture with the fusion of Arab, Western, and Byzantine influences. Palermo remained a leading artistic and commercial centre of the Mediterranean well into the Middle Ages.

Africa was reviving, however, as more organized and centralized states began to form in the later Middle Ages after the Renaissance of the 12th century. Motivated by religion and conquest, the kings of Europe launched a number of Crusades to try to roll back Muslim power and retake the Holy Land. The Crusades were unsuccessful but were far more effective in weakening the already tottering Byzantine Empire. They also rearranged the balance of power in the Muslim world as Egypt once again emerged as a major power.

Islamic culture and science

Religion always played a prevalent role in Middle Eastern culture, affecting learning, architecture, and the ebb and flow of cultures. When Muhammad introduced Islam, it jump-started Middle Eastern culture, inspiring achievements in architecture, the revival of old advances in science and technology, and the formation of a distinct way of life. Islam primarily consisted of the five pillars of belief, including confession of faith, the five prayers a day, to fast during the holy month of Ramadan, to pay the tax for charity (the zakāt), and the hajj, or the pilgrimage that a Muslim needed to take at least once in their lifetime, according to the five (or six) pillars of Islam. Islam also created the need for spectacularly built mosques which created a distinct form of architecture. Some of the more magnificent mosques include the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the former Mosque of Cordoba. Islam unified the Middle East and helped the empires there to remain stable. Missionaries and warriors spread the religion from Arabia to North and Sudanic Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and the Mesopotamia area. This created a mix of cultures, especially in Africa, and the mawali demographic. Although the mawali would experience discrimination from the Umayyad, they would gain widespread acceptance from the Abbasids and it was because of this that allowed for mass conversions in foreign areas. "People of the book" or dhimmi were always treated well; these people included Christians, Jews, Hindus, and Zoroastrians. However, the crusades started a new thinking in the Islamic empires, that non-Islamic ideas were immoral or inferior; this was primarily perpetrated by the ulama (علماء) scholars.

Arabian culture took off during the early Abbasid age, despite the prevalent political issues. Muslims saved and spread Greek advances in medicine, algebra, geometry, astronomy, anatomy, and ethics that would later find its way back to Western Europe. The works of Aristotle, Galen, Hippocrates, Ptolemy, and Euclid were saved and distributed throughout the empire (and eventually into Europe) in this manner. Muslim scholars also discovered the Hindu–Arabic numeral system in their conquests of south Asia. The use of this system in Muslim trade and political institutions allowed for the eventual popularization of it around the world; this number system would be critical to the Scientific revolution in Europe. Muslim intellectuals would become experts in chemistry, optics, and mapmaking during the Abbasid Caliphate. In the arts, Abbasid architecture expanded upon Umayyad architecture, with larger and more extravagant mosques. Persian literature grew based on ethical values. Astronomy was stressed in art. Much of this learning would find its way to the West. This was especially true during the crusades, as warriors would bring back Muslim treasures, weapons, and medicinal methods.

Turks, Crusaders, and Mongols

The dominance of the Arabs came to a sudden end in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuq Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands in Central Asia. They conquered Persia, Iraq (capturing Baghdad in 1055), Syria, Palestine, and the Hejaz. Egypt held out under the Fatimid caliphs until 1169, when it too fell to the Turks.

Despite massive territorial losses in the 7th century, the Christian Byzantine Empire continued to be a potent military and economic force in the Mediterranean, preventing Arab expansion into much of Europe. The Seljuqs' defeat of the Byzantine military in the Battle of Manzikert in the 11th century and settling in Anatolia effectively marked the end of Byzantine power. The Seljuks ruled most of the Middle East region for the next 200 years, but their empire soon broke up into a number of smaller sultanates.

Christian Western Europe staged a remarkable economic and demographic recovery in the 11th century since its nadir in the 7th century. The fragmentation of the Middle East allowed joined forces, mainly from England, France, and the emerging Holy Roman Empire, to enter the region. In 1095, Pope Urban II responded to pleas from the flagging Byzantine Empire and summoned the European aristocracy to recapture the Holy Land for Christianity. In 1099 the knights of the First Crusade captured Jerusalem and founded the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which survived until 1187, when Saladin, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, retook the city. Smaller crusader kingdoms and fiefdoms survived until 1291.

Mongol rule

The conquest of Baghdad and the death of the caliph in 1258 officiated the end of the Abbasid Caliphate and annexed its territories to the Mongol Empire, excluding Mamluk Egypt and the majority of Arabia. When the Khagan (or Great Khan) of the Mongol Empire, Möngke Khan, died in 1259, any further expansion by Hulegu was halted, as he had to return to the Mongol capital Karakorum for the election of a new khagan. His absence resulted in the first defeat of the Mongols (by the Mamluk Egyptians) during the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260. Issues began to arise when the Mongols grew increasingly unable to reach a consensus as to whom to elect khagan. Additionally, societal clashing occurred between traditionalists who wished to retain their nomadic culture and Mongols moving towards sedentary agriculture. All of this led to the fragmentation of the empire in 1260. Hulegu carved out his Middle Eastern territory into the independent Ilkhanate, which included most of Armenia, Anatolia, Azerbaijan, Mesopotamia, and Iran.

The Mongols eventually retreated in 1335, but the chaos that ensued throughout the empire deposed the Seljuq Turks. In 1401, the region was further plagued by the Turko-Mongol, Timur, and his ferocious raids. By then, another group of Turks had arisen as well, the Ottomans. Based in Anatolia, by 1566 they would conquer the Iraq-Iran region, the Balkans, Greece, Byzantium, most of Egypt, most of north Africa, and parts of Arabia, unifying them under the Ottoman Empire. The rule of the Ottoman sultans marked the end of the Medieval (Postclassical) Era in the Middle East.

Early Modern Near East

The Ottoman Empire (1299–1918)

By the early 15th century, a new power had arisen in western Anatolia, the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman khans, who in 1453 captured the Christian Byzantine capitol of Constantinople and made themselves sultans. The Mamluks held the Ottomans out of the Middle East for a century, but in 1514 Selim the Grim began the systematic Ottoman conquest of the region. Syria was occupied in 1516 and Egypt in 1517, extinguishing the Mameluk line. Iraq was conquered almost in 40 years from the Iranian Safavids, who were successors of the Aq Qoyunlu.

The Ottomans united the whole region under one ruler for the first time since the reign of the Abbasid caliphs of the 10th century, and they kept control of it for 400 years, despite brief intermissions created by the Iranian Safavids and Afsharids. By this time the Ottomans also held Greece, the Balkans, and most of Hungary, setting the new frontier between east and west far to the north of the Danube.

In the west, Europe was rapidly expanding, demographically, economically, and culturally. By 1700, the Ottomans had been driven out of Hungary. Although some areas of Ottoman Europe, such as Albania and Bosnia, saw many conversions to Islam, the area was never culturally absorbed into the Muslim world. From 1768 to 1918, the Ottomans gradually lost territory. By the 19th century, Europe had overtaken the Muslim world in wealth, population, and—most importantly—technology. The industrial revolution fueled a boom that laid the foundations for the growth of capitalism. During the 19th century, Greece, Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria claimed independence, and the Ottoman Empire became known as the "sick man of Europe", increasingly under the financial control of European powers. Domination soon turned to outright conquest: the French annexed Algeria in 1830 and Tunisia in 1878 and the British occupied Egypt in 1882, though it remained under nominal Ottoman sovereignty. In the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 the Ottomans were driven out of Europe altogether, except for the city of Constantinople and its hinterland.

The British also established effective control of the Persian Gulf, and the French extended their influence into Lebanon and Syria. In 1912, the Italians seized Libya and the Dodecanese islands, just off the coast of the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia. The Ottomans turned to Germany to protect them from the western powers, but the result was increasing financial and military dependence on Germany.

Ottoman reform efforts

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Middle Eastern rulers tried to modernize their states to compete more effectively with Europe. In the Ottoman Empire, the Tanzimat reforms re-invigorated Ottoman rule and were furthered by the Young Ottomans in the late 19th century, leading to the First Constitutional Era in the Empire that included the writing of the 1876 constitution and the establishment of the Ottoman Parliament. The authors of the 1906 revolution in Persia all sought to import versions of the western model of constitutional government, civil law, secular education, and industrial development into their countries. Throughout the region, railways and telegraph lines were constructed, schools and universities were opened, and a new class of army officers, lawyers, teachers, and administrators emerged, challenging the traditional leadership of Islamic scholars.

This first Ottoman constitutional experiment ended soon after it began, however, when the autocratic Sultan Abdul Hamid II abolished the parliament and the constitution in favor of personal rule. Abdul Hamid ruled by decree for the next 30 years, stirring democratic resentment. The reform movement known as the Young Turks emerged in the 1890s against his rule, which included massacres against minorities. The Young Turks seized power in the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and established the Second Constitutional Era, leading to a pluralist and multiparty elections in the Empire for the first time in 1908. The Young Turks split into two parties, the pro-German and pro-centralization Committee of Union and Progress and the pro-British and pro-decentralization Freedom and Accord Party. The former was led by an ambitious pair of army officers, Ismail Enver Bey (later Pasha) and Ahmed Cemal Pasha, and a radical lawyer, Mehmed Talaat Bey (later Pasha). After a power struggle between the two parties of Young Turks, the Committee emerged victorious and became a ruling junta, with Talaat as Grand Vizier and Enver as War Minister, and established a German-funded modernisation program across the Empire.

Enver Bey's alliance with Germany, which he considered the most advanced military power in Europe, was enabled by British demands that the Ottoman Empire cede their formal capital Edirne (Adrianople) to the Bulgarians after losing the First Balkan War, which the Turks saw as a betrayal by Britain. These demands cost Britain the support of the Turks, as the pro-British Freedom and Accord Party was now repressed under the pro-German Committee for, in Enver's words, "shamefully delivering the country to the enemy" (Britain) after agreeing to the demands to give up Edirne.

Modern Middle East

Final years of the Ottoman Empire

In 1878, as the result of the Cyprus Convention, the United Kingdom took over the government of Cyprus as a protectorate from the Ottoman Empire. While the Cypriots at first welcomed British rule, hoping that they would gradually achieve prosperity, democracy and national liberation, they soon became disillusioned. The British imposed heavy taxes to cover the compensation they paid to the Sultan for conceding Cyprus to them. Moreover, the people were not given the right to participate in the administration of the island, since all powers were reserved to the High Commissioner and to London.

Meanwhile, the fall of the Ottomans and the partitioning of Anatolia by the Allies led to resistance by the Turkish population, under the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Turkish victory against the invading powers during the Turkish War of Independence, and the founding of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923. As the first President of Turkey, Atatürk embarked on a program of modernisation and secularisation. He abolished the caliphate, emancipated women, enforced western dress and the use of a new Turkish alphabet based on Latin script in place of the Arabic alphabet, and abolished the jurisdiction of the Islamic courts. In effect, Turkey, having given up rule over the Arab world, was now determined to secede from the Middle East and become culturally part of Europe.

Another turning point came when oil was discovered, first in Persia (1908) and later in Saudi Arabia (1938) as well as the other Persian Gulf states, Libya, and Algeria. The Middle East, it turned out, possessed the world's largest easily untapped reserves of crude oil, the most important commodity in the 20th century. The kings and emirs of these oil states became immensely wealthy exporting petroleum to the west, allowing them to consolidate their hold on power and giving them a stake in preserving western hegemony over the region.

A Western dependence on Middle Eastern oil and the decline of British influence led to a growing American interest in the region. Initially, the Western oil companies established a dominance over oil production and extraction. However, indigenous movements towards nationalizing oil assets, oil sharing, and the advent of OPEC ensured a shift in the balance of power towards the Arab oil states. Oil wealth also had the effect of suffocating whatever economic, political, or social reform might have emerged in the Arab world under the influence of the Kemalist revolution in Turkey.

World War I

In 1914, Enver Pasha's alliance with Germany led the Ottoman Empire into the fatal step of joining Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I, against Britain and France. The British saw the Ottomans as the weak link in the enemy alliance, and concentrated on knocking them out of the war. When a direct assault failed at Gallipoli in 1915, they turned to fomenting revolution in the Ottoman domains, exploiting the awakening force of Arab, Armenian, and Assyrian nationalism against the Ottomans.

The British found an ally in Sharif Hussein, the hereditary ruler of Mecca (and believed by Muslims to be a descendant of Muhammad), who led an Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule, after being promised independence.

The Allies, led by Britain, won the war and seized most of the Ottoman territories; Turkey just managed to survive. The war transformed the region in terms of increased British and French involvement; the creation of the Middle Eastern state system as seen in Turkey and Saudi Arabia; the emergence of explicitly more nationalist politics, as seen in Turkey and Egypt; and the rapid growth of the Middle Eastern oil industry.

Ottoman defeat and partition (1918–22)

When the Ottoman Empire was defeated by an Arab uprising and the British forces after the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in 1918, the Arab population did not get what it wanted. Islamic activists of more recent times have described it as an Anglo-French betrayal. British and French governments concluded a secret treaty (the Sykes–Picot Agreement) to partition the Middle East between them. The British in 1917 announced the Balfour Declaration promised the international Zionist movement their support in re-creating the historic Jewish homeland in Palestine.

When the Ottomans departed, the Arabs proclaimed an independent state in Damascus, but were too weak, militarily and economically, to resist the European powers for long, and Britain and France soon established control and re-arranged the Middle East to suit themselves.

Syria became a French protectorate as a League of Nations mandate. The Christian coastal areas were split off to become Lebanon, another French protectorate. Iraq and Palestine became British mandated territories. Iraq became the "Kingdom of Iraq" and one of Sharif Hussein's sons, Faisal, was installed as the King of Iraq. Iraq incorporated large populations of Kurds, Assyrians and Turkmens, many of whom had been promised independent states of their own.

Britain was granted a Mandate for Palestine on 25 April 1920 at the San Remo Conference, and, on 24 July 1922, this mandate was approved by the League of Nations. Palestine became the "British Mandate of Palestine" and was placed under direct British administration. The Jewish population of Palestine which numbered less than 8 percent in 1918 was given free rein to immigrate, buy land from absentee landlords, set up a shadow government in waiting and establish the nucleus of a state under the protection of the British Army which suppressed a Palestinian revolt in 1936. The Territory East of the Jordan River was added to the British Mandate by the Transjordan Memorandum, which was a British memorandum passed by the Council of the League of Nations on 16 September 1922. Most of the Arabian peninsula fell to another British ally, Ibn Saud. Saud created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932.

1920–1945

During the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Syria and Egypt made moves towards independence. In 1919, Egypt's Saad Zaghloul orchestrated mass demonstrations in Egypt known as the First Revolution. While Zaghloul would later become Prime Minister, the British repression of the anticolonial riots led to around 800 deaths. In 1920, Syrian forces were defeated by the French in the Battle of Maysalun and Iraqi forces were defeated by the British when they revolted. In 1922, the (nominally) independent Kingdom of Egypt was created following the British government's issuance of the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence.

Although the Kingdom of Egypt was technically "neutral" during World War II, Cairo soon became a major military base for the British and the country was occupied. The British cited the 1936 treaty that allowed it to station troops on Egyptian soil to protect the Suez Canal. In 1941, the Rashīd `Alī al-Gaylānī coup in Iraq led to the British to invade, leading to the Anglo-Iraqi War. This was followed by the Allied invasion of Syria–Lebanon and the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran.

In Palestine, conflicting forces of Arab nationalism and Zionism created a situation the British could neither resolve nor extricate themselves from. The rise of German dictator Adolf Hitler had created a new urgency in the Zionist quest to immigrate to Palestine and create a Jewish state. A Palestinian state was also an attractive alternative to the Arab and Persian leaders, instead of the de facto British, French, and perceived Jewish colonialism or imperialism, under the logic of "the enemy of my enemy is my friend".

New states after World War II

The British, French, and Soviets departed from many parts of the Middle East during and after World War II. Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the states in the Arabian Peninsula generally kept their boundaries. After the war, however, seven Middle East states gained (or regained) their independence:

- 22 November 1943 – Lebanon

- 1 January 1944 – Syria

- 22 May 1946 – Jordan (British mandate ended)

- 1947 – Iraq (forces of the United Kingdom withdrawn)

- 1947 – Egypt (forces of the United Kingdom withdrawn to the Suez Canal area)

- 1948 – Israel (forces of the United Kingdom withdrawn)

- August 16, 1960 – Cyprus

The struggle between the Arabs and the Jews in Palestine culminated in the 1947 United Nations plan to partition Palestine. This plan sought to create an Arab state and a separate Jewish state in the narrow space between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean. The Jewish leaders accepted it, but the Arab leaders rejected this plan.

On 14 May 1948, when the British Mandate expired, the Zionist leadership declared the State of Israel. In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War which immediately followed, the armies of Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia intervened and were defeated by Israel. About 800,000 Palestinians fled from areas annexed by Israel and became refugees in neighbouring countries, thus creating the "Palestinian problem", which has troubled the region ever since. Approximately two-thirds of 758,000–866,000 of the Jews expelled or who fled from Arab lands after 1948 were absorbed and naturalized by the State of Israel.

On August 16, 1960, Cyprus gained its independence from the United Kingdom. Archbishop Makarios III, a charismatic religious and political leader, was elected its first independent president, and in 1961 it became the 99th member of the United Nations.

Modern states

The modern Middle East was shaped by three things: departure of European powers, the founding of Israel, and the growing importance of the oil industry. These developments eventually led to increased U.S. involvement in the region. The United States was the ultimate guarantor of the region's stability as well as the dominant force in the oil industry after the 1950s. When revolutions brought radical anti-Western regimes to power in Egypt (1954), Syria (1963), Iraq (1968), and Libya (1969), the Soviet Union, seeking to open a new arena of the Cold War, allied itself with Arab socialist rulers like Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt and Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

These regimes gained popular support with promises to destroy the state of Israel and other "western imperialists", and to bring prosperity to the Arab masses. When the Six-Day War of 1967 ended with an overwhelming Israeli victory, many viewed the defeat as the failure of Arab socialism. This represents a turning point when "fundamental and militant Islam began to fill the political vacuum created".

The United States, in response, felt obliged to defend its remaining allies, the monarchies of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iran, and the Persian Gulf emirates, whose methods of rule were often almost as unattractive in western eyes as those of the anti-western regimes. Iran in particular became a key U.S. ally, until a revolution led by the Shi'a clergy overthrew the monarchy in 1979 and established a theocratic state that proved to be far more anti-western than the secular regimes in Iraq or Syria. The list of Arab-Israeli wars includes a great number of major wars such as 1948 Arab–Israeli War, 1956 Suez War, 1967 Six-Day War, 1967-1970 War of Attrition, 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1982 Lebanon War, as well as a number of lesser conflicts of lower intensity.

In Cyprus between 1955 and 1974, conflict arising between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots led to Cypriot intercommunal violence and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. The Cyprus dispute remains unresolved.

In the mid-to-late 1960s, the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party led by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar took power in both Iraq and Syria. Iraq was first ruled by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, but was succeeded by Saddam Hussein in 1979, and Syria was ruled first by a Military Committee led by Salah Jadid, and later Hafez al-Assad until 2000, when he was succeeded by his son, Bashar al-Assad.

In 1979, Egypt under Nasser's successor, Anwar Sadat, concluded a peace treaty with Israel, ending the prospects of a united Arab military front. From the 1970s the Palestinians, led by Yasser Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization, resorted to a prolonged campaign of violence against Israel and against American, Jewish, and western targets generally, as a means of weakening Israeli resolve and undermining western support for Israel. The Palestinians were supported in this, to varying degrees, by the regimes in Syria, Libya, Iran, and Iraq. The high point of this campaign came in the 1975 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 condemning Zionism as a form of racism and the reception given to Arafat by the United Nations General Assembly. Resolution 3379 was revoked in 1991 by the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 4686.

Due to many of the frantic events of the late 1970s in the Middle East it culminated in the Iran–Iraq War between neighbouring Iran and Iraq. The war, started by Iraq, who invaded Iranian Khuzestan in 1980 at the behest of the latter's chaotic state of country due to the 1979 Islamic Revolution, eventually turned into a stalemate with hundreds of thousands of dead on both sides.

The fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of communism in the early 1990s had several consequences for the Middle East. It allowed large numbers of Soviet Jews to emigrate from Russia and Ukraine to Israel, further strengthening the Jewish state. It cut off the easiest source of credit, armaments, and diplomatic support to the anti-western Arab regimes, weakening their position. It opened up the prospect of cheap oil from Russia, driving down the price of oil and reducing the west's dependence on oil from the Arab states. It discredited the model of development through authoritarian state socialism, which Egypt (under Nasser), Algeria, Syria, and Iraq had followed since the 1960s, leaving these regimes politically and economically stranded. Rulers such as Iraq's Saddam Hussein increasingly relied on Arab nationalism as a substitute for socialism.

Saddam Hussein led Iraq into a prolonged and costly war with Iran from 1980 to 1988, and then into its fateful invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Kuwait had been part of the Ottoman province of Basra before 1918, and thus in a sense part of Iraq, even though Iraq had recognized its independence in 1961. In response, the United States formed a coalition of allies with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Syria, gained UN approval, and evicted Iraq from Kuwait by force in the Gulf War. President George H. W. Bush did not, however, attempt to overthrow Saddam Hussein, which the United States later came to regret. The Gulf War led to a permanent U.S. military presence in the Persian Gulf, particularly in Saudi Arabia, which offended many Muslims, and was a reason often cited by Osama bin Laden as justification for the September 11 attacks.

1990s–present

The worldwide change of governance in Eastern Europe, Latin America, East Asia, and parts of Africa following the dissolution of the Soviet Union did not occur in the Middle East. In the whole region, only Israel, Turkey and to some extent Lebanon and the Palestinian territories were considered to be democracies. Some countries had legislative bodies, but these were said to have little power. In the Persian Gulf states the majority of the population could not vote because they were guest workers rather than citizens.

In most Middle Eastern countries, the growth of market economies was said to be limited by political restrictions, corruption, and cronyism, overspending on arms and prestige projects and over-dependence on oil revenues. The successful economies were countries that had oil wealth and low populations, such as Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, where the ruling emirs allowed some political and social liberalization, but without giving up any of their own power. Lebanon also rebuilt a fairly successful economy after a prolonged civil war in the 1980s.

At the beginning of the 21st century, all these factors intensified conflict in the Middle East, which affected the entire world. Bill Clinton's failed attempt to broker a peace deal between Israel and Palestine at the Camp David Summit in 2000 led directly to the election of Ariel Sharon as Prime Minister of Israel and to the Second Intifada, which conducted suicide bombings on Israeli civilians. This was the first major outbreak of violence since the Oslo Peace Accords of 1993.

At the same time, the failures of most of the Arab governments and the bankruptcy of secular Arab radicalism led a section of educated Arabs (and other Muslims) to embrace Islamism, promoted both by Iran's Shi'a clerics as well as by Saudi Arabia's powerful Wahhabist sect. Many of the militant Islamists gained their military training while fighting Soviet forces in Afghanistan.[dubious ] Many of the Afghan jihadists, though supposedly none of the Arab volunteers, were funded by the United States under Operation Cyclone as part of the Reagan Doctrine, one of the longest and most expensive CIA covert operations ever.

One of these Arab militants was a wealthy Saudi Arabian named Osama bin Laden. After fighting against the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, he formed the al-Qaida organization, which was responsible for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, the USS Cole bombing and the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States. The September 11 attacks led the George W. Bush administration to invade Afghanistan in 2001 to overthrow the Taliban regime, which had been harbouring Bin Laden and al-Qaida. The United States and its allies described this operation as part of a global "War on Terror".

In 2002, U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld developed a plan to invade Iraq, remove Saddam from power, and turn Iraq into a democratic state with a free-market economy, which they hoped would serve as a model for the rest of the Middle East. The United States and its principal allies—Britain, Italy, Spain, and Australia—could not secure United Nations approval for the execution of the numerous UN resolutions, so they launched an invasion of Iraq and deposed Saddam without much difficulty in April 2003.

The advent of a new western army of occupation in a Middle Eastern capital marked a turning point in the history of the region. Despite successful elections (although boycotted by large portions of Iraq's Sunni population) held in January 2005, much of Iraq had all but disintegrated, due to a post-war insurgency which morphed into persistent ethnic violence that the American army was initially unable to quell. Many of Iraq's intellectual and business elite fled the country, and many Iraqi refugees left as a result of the insurgency, further destabilizing the region. A responsive surge in U.S. forces in Iraq was largely successful in controlling the insurgency and stabilizing the country. U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq by December 2011.

By 2005, President George W. Bush's Road map for peace between Israel and the Palestinians was stalled, although this situation had begun to change with Yasser Arafat's death in 2004. In response, Israel moved towards a unilateral solution, pushing ahead with the Israeli West Bank barrier to protect Israel from Palestinian suicide bombers and proposed unilateral withdrawal from Gaza. In 2006 a new conflict erupted between Israel and Hezbollah Shi'a militia in southern Lebanon, further setting back any "prospects for peace".

In the early 2010s, a revolutionary wave popularly known as the Arab Spring brought major protests, uprisings, and revolutions to several Middle Eastern countries, followed by prolonged civil wars in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. In 2014, a terrorist group and self-proclaimed caliphate calling itself the Islamic State made rapid territorial gains in western Iraq and eastern Syria, prompting international military intervention. At its peak, the group controlled an area containing an estimated 2.8 to 8 million people, 98% of which was lost by December 2017.