From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Human–wildlife conflict (HWC) refers to the negative interactions between human and wild animals,

with undesirable consequences both for people and their resources, on

the one hand, and wildlife and their habitats on the other (IUCN 2020). HWC, caused by competition for natural resources between human and wildlife, influences human food security

and the well-being of both humans and animals. In many regions, the

number of these conflicts has increased in recent decades as a result of

human population growth and the transformation of land use.

HWC is a serious global threat to sustainable development, food security and conservation in urban and rural landscapes alike. In general, the consequences of HWC include: crop destruction, reduced agricultural productivity, competition for grazing lands and water supply, livestock predation, injury and death to human, damage to infrastructure, and increased risk of disease transmission among wildlife and livestock.

With specific reference to forests, a high density of large ungulates such as deer, can cause severe damage to the vegetation and can threaten regeneration by trampling or browsing small trees, rubbing themselves on trees or stripping tree bark. This behavior can have important economic implications and can lead to polarization between forest and wildlife managers (CPW, 2016).

Previously, conflict mitigation strategies utilized lethal control, translocation, population size regulation and endangered species preservation. Recent management now uses an interdisciplinary set of approaches to solving conflicts. These include applying scientific research, sociological studies and the arts

to reducing conflicts. As human-wildlife conflict inflicts direct and

indirect consequences on people and animals, its mitigation is an

important priority for the management of biodiversity and protected areas.

Resolving human-wildlife conflicts and fostering coexistence requires

well-informed, holistic and collaborative processes that take into

account underlying social, cultural and economic contexts.

Many countries are starting to explicitly include human-wildlife

conflict in national policies and strategies for wildlife management,

development and poverty alleviation. At the national level,

cross-sectoral collaboration between forestry, wildlife, agriculture,

livestock and other relevant sectors is key.

Meaning

Human–wildlife conflict is defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature

(WWF) as "any interaction between humans and wildlife that results in

negative impacts of human social, economic or cultural life, on the

conservation of wildlife populations, or on the environment. The Creating Co-existence

workshop at the 5th Annual World Parks Congress (8–17 September 2003,

Montreal) defined human-wildlife conflict in the context of human goals

and animal needs as follows: “Human-wildlife conflict occurs when the

needs and behavior of wildlife impact negatively on the goals of humans

or when the goals of humans negatively impact the needs of wildlife."

A 2007 review by the United States Geological Survey

defines human-wildlife conflict in two contexts; firstly, actions by

wildlife conflict with human goals i.e. life, livelihood and life-style,

and secondly, human activities that threaten the safety and survival of

wildlife. However, in both cases outcomes are decided by human

responses to the interactions.

The Government of Yukon

defines human-wildlife conflict simply, but through the lens of damage

to property, i.e. "any interaction between wildlife and humans which

causes harm, whether it’s to the human, the wild animal, or property." Here, property includes buildings, equipment and camps, livestock and pets, but does not include crops, fields or fences.

The IUCN SSC Human-Wildlife Conflict Task Force

describes human-wildlife conflict as "struggles that emerge when the

presence or behaviour of wildlife poses actual or perceived, direct and

recurring threat to human interests or needs, leading to disagreements

between groups of people and negative impacts on people and/or

wildlife".

History

Human-wildlife

interactions have occurred throughout man's prehistory and recorded

history. Among the early forms of human-wildlife conflict is the

depredation of the ancestors of prehistoric man by a number of predators

of the Miocene such as saber-toothed cats, leopards, and spotted hyenas.

Fossil remains of early hominids show evidence of depredation; the Taung Child, the fossilized skull of a young Australopithecus africanus,

is thought to have been killed by an eagle from the distinct marks on

its skull and the fossil having been found among egg shells and remains

of small animals.

A Plio-Pleistocene horned crocodile, Crocodylus anthropophagus, whose fossil remains have been recorded from Olduvai Gorge, was the largest predator encountered by prehistoric man, as indicated by hominid specimens preserving crocodile bite marks from these sites.

Examples

Simultaneous use of water resources by humans and crocodiles sets up occasions for human-wildlife conflict

Asian elephant damage to houses

Africa

As a tropical continent with substantial anthropogenic development, Africa is a hotspot for biodiversity and therefore, for human-wildlife conflict. Two of the primary examples of conflict in Africa are human-predator (lions, leopards, cheetahs, etc.) and human-elephant conflict. Depredation of livestock by African predators is well documented in Kenya, Namibia, Botswana, and more. African elephants

frequently clash with humans, as their long-distance migrations often

intersect with farms. The resulting damage to crops, infrastructure, and

at times, people, can lead to the retaliatory killing of elephants by

locals.

In 2017, more than 8 000 human-wildlife conflict incidents were

reported in Namibia alone (World Bank, 2019). Hyenas killed more than

600 cattle in the Zambezi Region of Namibia between 2011 and 2016 and

there were more than 4 000 incidents of crop damage, mostly caused by

elephants moving through the region (NACSO, 2017a).

Asia

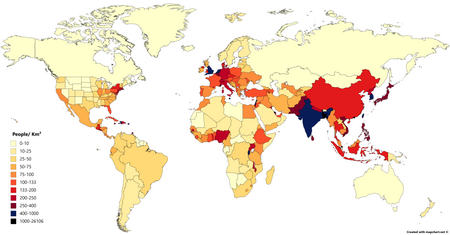

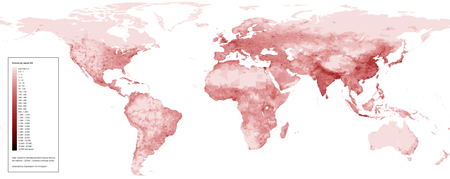

With a rapidly increasing human population and high biodiversity,

interactions between people and wild animals are becoming more and more

prevalent. Like human-predator in Africa, encounters between tigers,

people, and their livestock is a prominent issue on the Asian continent.

Attacks on humans and livestock have exacerbated major threats to tiger conservation such as mortality, removal of individuals from the wild, and negative perceptions of the animals from locals. Even non-predator conflicts are common, with crop-raiding by elephants and macaques

persisting in both rural and urban environments, respectively. Poor

disposal of hotel waste in tourism-dominated towns have altered

behaviours of carnivores such as sloth bears that usually avoid human

habitation and human-generated garbage.

In Sri Lanka, for example, each year as many as 80 people are

killed by elephants and more than 230 elephants are killed by farmers.

The Sri Lankan elephant is listed as endangered, and only 2 500–4 000

individuals remain in the wild (IIED, 2019).

In India the conflict is exceedingly acute because of the country's Wildlife Protection Act.

Antarctica

The first instance of death due to human-wildlife conflict in Antarctica occurred in 2003 when a leopard seal dragged a snorkelling British marine biologist underwater where she drowned.

Europe

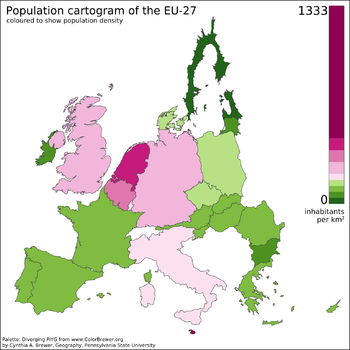

Human–wildlife

conflict in Europe includes interactions between people and both

carnivores and herbivores. A variety of non-predators such as deer, wild boar, rodents, and starlings have been shown to damage crops and forests. Carnivores like raptors and bears create conflict with humans by eating both farmed and wild fish, while others like lynxes and wolves prey upon livestock.

Even less apparent cases of human-wildlife conflict can cause

substantial losses; 500,000 deer-vehicle collisions in Europe (and 1-1.5

million in North America) led to 30,000 injuries and 200 deaths.

North America

Instances of human-wildlife conflict are widespread in North America. In

Wisconsin, United States wolf depredation of livestock is a prominent

issue that resulted in the injury or death of 377 domestic animals over a

24-year span. Similar incidents were reported in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem, with reports of wolves killing pets and livestock.

Expanding urban centers have created increasing human-wildlife

conflicts, with interactions between human and coyotes and mountain

lions documented in cities in Colorado and California, respectively,

among others. Big cats are a similar source of conflict in Central Mexico, where reports of livestock depredation are widespread, while interactions between humans and coyotes were observed in Canadian cities as well.

Diagram of Human Wildlife Conflict in Expanding American Cities

Oceania

On K'gari-Fraser Island in Australia, attacks by wild dingoes on humans (including the well-publicized death of a child) created a human-wildlife crisis that required scientific intervention to manage. In New Zealand, distrust and dislike of introducing predatory birds (such as the New Zealand falcon) to vineyard landscapes led to tensions between people and the surrounding wildlife. In extreme cases large birds have been reported to attack people who approach their nests, with human-magpie conflict in Australia a well-known example. Even conflict in urban environments has been documented, with development increasing the frequency of human-possum interactions in Sydney.

The Emu War

is another example of oceanic human-wildlife conflict where the

Australian government famously sent two soldier into south Australia to

hunt and kill Emu's.

South America

As

with most continents, the depredation of livestock by wild animals is a

primary source of human-wildlife conflict in South America. The

killings of guanacos

by predators in Patagonia, Chile – which possess both economic and

cultural value in the region – have created tensions between ranchers

and wildlife. South America's only species of bear, the Andean Bear, faces population declines due to similar conflict with livestock owners in countries like Ecuador.

Marine ecosystems

Human–wildlife

conflict is not limited to terrestrial ecosystems, but is prevalent in

the world's oceans as well. As with terrestrial conflict, human-wildlife

conflict in aquatic environments is incredibly diverse and extends

across the globe. In Hawaii, for example, an increase in monk seals around the islands has created a conflict between locals who believe that seals “belong” and those who do not. Marine predators such as killer whales and fur seals compete with fisheries for food and resources, while others like great white sharks have a history of injuring humans.

While many of the causes of human-wildlife conflict are the same

between terrestrial and marine ecosystems (depredation, competition,

human injury, etc.), ocean environments are less studied and management

approaches often differ.

Mitigation strategies

A

traditional livestock corral surrounded by a predator-proof corral in

South Gobi desert, Mongolia, to protect livestock from predators like

snow leopard and wolf.

Mitigation strategies for

managing human-wildlife conflict vary significantly depending on

location and type of conflict. The preference is always for passive,

non-intrusive prevention measures but often active intervention is

required to be carried out in conjunction.

Regardless of approach, the most successful solutions are those that

include local communities in the planning, implementation, and

maintenance. Resolving conflicts, therefore, often requires a regional plan of attack with a response tailored to the specific crisis. Still, there are a variety of management techniques that are frequently employed to mitigate conflicts. Examples include:

- Translocation of problematic animals:

Relocating so-called "problem" animals from a site of conflict to a new

place is a mitigation technique used in the past, although recent

research has shown that this approach can have detrimental impacts on

species and is largely ineffective.

Translocation can decrease survival rates and lead to extreme dispersal

movements for a species, and often "problem" animals will resume

conflict behaviors in their new location.

- Erection of fences or other barriers: Building barriers around cattle bomas, creating distinct wildlife corridors, and erecting beehive fences around farms to deter elephants have all demonstrated the ability to be successful and cost-effective strategies for mitigating human-wildlife conflict.

- Improving community education and perception of animals:

Various cultures have myriad views and values associated with the

natural world, and how wildlife is perceived can play a role in

exacerbating or alleviating human-wildlife conflict. In one Masaai

community where young men once obtained status by killing lions,

conservationists worked with community leaders to shift perceptions and

allow those young men to achieve the same social status by protecting

lions instead.

- Effective land use planning: altering land use practices can help mitigate conflict between humans and crop-raiding animals. For example, in Mozambique, communities started to grow more chili pepper plants after making the discovery that elephants dislike and avoid plants containing capsaicin.

This creative and effective method discourages elephants from trampling

community farmers' fields as well as protects the species.

- Compensation: in some cases, governmental systems have been

established to offer monetary compensation for losses sustained due to

human-wildlife conflict. These systems hope to deter the need for

retaliatory killings of animals, and to financially incentivize the

co-existing of humans and wildlife. Compensation strategies have been employed in India, Italy, and South Africa,

to name a few. The success of compensation in managing human-wildlife

conflict has varied greatly due to under-compensation, a lack of local

participation, or a failure by the government to provide timely

payments.

- Spatial analyses and mapping conflict hotspots: mapping interactions and creating spatial models has been successful in mitigating human-carnivore conflict and human-elephant conflict,

among others. In Kenya, for example, using grid-based geographical

information systems in collaboration with simple statistical analyses

allowed conservationists to establish an effective predictor for

human-elephant conflict.

- Predator-deterring guard dogs:

The use of guard dogs to protect livestock from depredation has been

effective in mitigating human-carnivore conflict around the globe. A

recent review found that 15.4% of study cases researching

human-carnivore conflict used livestock-guarding dogs as a management

technique, with animal losses on average 60 times lower than the norm.

- Managing garbage and artificial feeding to prevent attraction of wildlife:

Many wildlife species are attracted to garbage, especially including

food wastes, leading to negative interactions with people.

Poor disposal of garbage such as hotel waste is rapidly emerging as an

important aspect that heightens human-carnivore conflicts in countries

such as India.

Urgent research to increase knowledge of the impact of easily available

garbage is needed, and improving management of garbage in areas where

carnivores reside is essential. Managing garbage disposal and artificial

feeding of primates can also reduce conflicts and opportunities for

disease transmission. One study found that prohibiting tourists from

feeding Japanese macaques reduced aggressive interactions between

macaques and people.

- Use of technology: Rapid technology development (especially Information Technology)

can play a vital role in the prevention of Human–wildlife conflict.

Drones and mobile applications can be used to detect the movements of

animals and warn highways and railways authorities to prevent collisions

of animals with vehicles and trains. SMS or WhatsApp messaging systems have also been used to alert people about the presence of animals in nearby areas. Early warning wireless systems have been successfully used in undulating and flat terrain to mitigate human-elephant conflict in Tamil Nadu, India.

Livestock guardian dogs can be an effective and popular way of deterring predators and reducing human-carnivore conflicts.

Hidden dimensions of the conflict

Human

wildlife conflict also has a range of hidden dimensions that are not

typically considered when the focus is on visible consequences. These

can include health impacts, opportunity costs, and transaction costs.

Case studies include work on elephants in northeast India, where

human-elephant interactions are correlated with increased imbibing of

alcohol by crop guardians with resultant enhanced mortality in

interactions, and issues related to gender in northern India.

In addition, research has shown that the fear caused by the presence of

predators can aggravate human-wildlife conflict more than the actual

damage produced by encounters.