Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were public displays of people, usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state. They were most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries. These displays sometimes emphasized the supposed inferiority of the exhibits' culture, and implied the superiority of "Western society", through tropes that purported marginalized groups as "savage". The idea of a "savage" derives from Columbus's voyages that deemed European culture remained pure, while other cultures were titled impure or "wild", and this stereotype relies heavily on the idea that different ways of living were "cast out by God", as other cultures do not recognize Christianity in relation to Creation. Throughout their existence such exhibitions garnered controversy over their demeaning, derogatory, and dehumanizing nature. They began as a part of circuses and "freak shows" which displayed exotic humans in a manner akin to a caricature which exaggerated their differences. They then developed into independent displays emphasizing the exhibits' inferiority to western culture and providing further justification for their subjugation. Such displays featured in multiple world's fairs and at temporary exhibitions in animal zoos.

One imperialist view of the whole non-Western world portrayed it as a vast animal park in which Whites could function as zookeepers—managers of the indigenous human and non-human inhabitants.

Animal zoos provide many controversies spanning to the modern day, as human expositions diminished in prominence in the 20th century.

Circuses and freak shows

The notion of the human curiosity has a history at least as long as colonialism. In the Western Hemisphere, one of the earliest-known zoos, that of Moctezuma in Mexico, consisted not only of a vast collection of animals, but also exhibited humans, for example, dwarves, albinos and hunchbacks.

During the Renaissance, the Medici developed a large menagerie in the Vatican. In the 16th century, Cardinal Hippolytus Medici had a collection of people of different races as well as exotic animals. He is reported as having a troupe of so-called Savages, speaking over twenty languages; there were also Moors, Tartars, Indians, Turks and Africans. In 1691, Englishman William Dampier exhibited a tattooed native of Miangas whom he bought when he was in Mindanao. He also intended to exhibit the man's mother to earn more profit, but the mother died at sea. The man was named Jeoly, falsely branded as "Prince Giolo" to attract more audience, and was exhibited for three months straight until he died of smallpox in London.

One of the first modern public human exhibitions was P.T. Barnum's exhibition of Joice Heth on 25 February 1835 and, subsequently, the Siamese twins Chang and Eng Bunker. These exhibitions were common in freak shows. Another famous example was that of Saartjie Baartman of the Namaqua, often referred to as the Hottentot Venus, who was displayed in London and France until her death in 1815.

During the 1850s, Maximo and Bartola, two microcephalic children from El Salvador, were exhibited in the US and Europe under the names Aztec Children and Aztec Lilliputians. However, human zoos would become common only in the 1870s in the midst of the New Imperialism period.

Start of human exhibits

In the 1870s, exhibitions of so-called "exotic populations" became popular throughout the western world. Human zoos could be seen in many of Europe's largest cities, such as Paris, Hamburg, London, Milan as well as American cities such as New York City and Chicago. Carl Hagenbeck, an animal trader, was one of the early proponents of this trend, when in 1874, at the suggestion of Heinrich Leutemann, he decided to exhibit Sami people with the 'Laplander Exhibition'. What differentiated Hagenbeck's exhibit from others, was the fact that he showed these people, with animals and plants, to "re-create", their "natural environment." He sold people the feeling of having travelled to these areas by witnessing his exhibits. These exhibits were a massive success, and only became larger and more elaborate. From this point forward human exhibitions would lean towards stereotyping, and projecting western superiority. Greater feeding into the Imperialist narrative, that these people's culture merited subjugation. It also promoted scientific racism, where they were classified as more or less 'civilized' on a scale, from great apes to western Europeans.

Hagenbeck would go on to launch a Nubian Exhibit in 1876, and an Inuit exhibit in 1880. These were also massively successful.

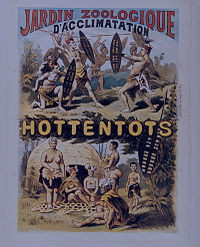

Aside from Hagenbeck, the Jardin d'Acclimatation was also a hotspot of ethnological exhibits. Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Jardin d'Acclimatation, decided in 1877 to organize two ethnological exhibits that also presented Nubians and Inuit. That year, the audience of the Jardin d'acclimatation' doubled to one million. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty ethnological exhibitions were presented at the Jardin zoologique d'acclimatation.

These displays were so successful they were incorporated into both the 1878 and the 1889 Parisian World's Fair, which presented a 'Negro Village'. Visited by 28 million people, the 1889 World's Fair displayed 400 indigenous people as the major attraction.

In Amsterdam the International Colonial and Export Exhibition had a display of people native to Suriname, in 1883.

In 1886, the Spanish displayed natives of the Philippines in an exhibition, as people whom they "civilized". This event added flame to the 1896 Philippine revolution. Queen Consort of Spain, Maria Cristina of Austria, afterwards institutionalized the business of human zoos. By 1887, indigenous Igorot people & animals were sent to Madrid and were exhibited in a human zoo at the newly constructed Palacio de Cristal del Retiro.

At both the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition Little Egypt a bellydancer, was photographed as a catalogued "type" by Charles Dudley Arnold and Harlow Higginbotha.

At the 1895 African Exhibition in The Crystal Palace, around eighty people from Somalia were displayed in an "exotic" setting.

German ethnographs

Ethnology studies in Germany took a new approach in the 1870s as human displays were incorporated into zoos. These exhibits were lauded as 'educational' to the general population by the scientific community. Very quickly, the exhibits were used as a way to show that Europeans had "evolved" into a 'superior', 'cosmopolitan' life.

In the late 19th century, German ethnographic museums were seen as an empirical study of human culture. They contained artifacts from cultures around the world organized by continent allowing visitors to see the similarities and differences between the groups and "form their own ideas".

Objectification in human zoos

Within the history of human zoos, there are patterns of overt sexual representation of displayed peoples, most frequently women. These objectifications often lead to treatment that reflect a lack of privacy and respect, including the dissection and display of bodies after death without consent.

An example of the sexualization of ethnically diverse women in Europe is Saartje Baartman, often referred to as her anglicized name Sarah Bartmann. Bartmann was displayed both when she was alive throughout England and Ireland and after her death in The Musée de l'Homme. While alive, she participated in a traveling show depicting her as a "savage female" with a large focus on her body. The clothes she was put in were tight and close to her skin color, and spectators were encouraged to "see for themselves" if Bartmann's body, particularly her buttocks, were real through "poking and pushing". Her living display was financially compensated but there is no record of her consenting to be examined and displayed after death.

Dominika Czarnecka theorizes of the relationship between the radicalization and sexualization of black female bodies in her journal article, "Black Female Bodies and the 'White' View." Czarnecka focuses on ethnographic shows that were prominent in Polish territory in the late 19th century. She argues that an essential part of why these shows were so popular is the display of the black female body. Although the women in the shows were meant to be depicting Amazon warriors, their wardrobe was not similar to amazonian dress, and there are several documentations of comments from spectators about their revealing clothes and their bodies.

Although women were most frequently objectified, there are a few instances of "exotic" men being displayed due to their favorable appearance. Angelo Solimann was brought to Italy as a slave from Central Africa in the 18th century, but ended up gaining a reputation in Viennese society for his fighting skills and vast knowledge about language and history. Upon his death in 1796, this positive association did not prevent his body being "stuffed and exhibited in the Viennese Natural History Museum" for almost a decade.

Around the turn of the century

In 1896, to increase the number of visitors, the Cincinnati Zoo invited one hundred Sioux Native Americans to establish a village at the site. The Sioux lived at the zoo for three months.

The 1900 World's Fair presented the famous diorama living in Madagascar, while the Colonial exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) also displayed humans in cages, often nude or semi-nude. The 1931 exhibition in Paris was so successful that 34 million people attended it in six months, while a smaller counter-exhibition entitled The Truth on the Colonies, organized by the Communist Party, attracted very few visitors—in the first room, it recalled Albert Londres and André Gide's critiques of forced labour in the colonies. Nomadic Senegalese Villages were also presented.

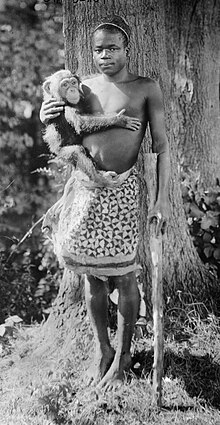

In 1906, Madison Grant—socialite, eugenicist, amateur anthropologist, and head of the New York Zoological Society—had Congolese pygmy Ota Benga put on display at the Bronx Zoo in New York City alongside apes and other animals. At the behest of Grant, the zoo director William Hornaday placed Benga displayed in a cage with the chimpanzees, then with an orangutan named Dohong, and a parrot, and labeled him The Missing Link, suggesting that in evolutionary terms Africans like Benga were closer to apes than were Europeans. It triggered protests from the city's clergymen, but the public reportedly flocked to see it.

On Monday, 8 September 1906, after just two days, Hornaday decided to close the exhibition, and Benga could be found walking the zoo grounds, often followed by a crowd "howling, jeering and yelling."

First organized backlash

According to The New York Times, although "few expressed audible objection to the sight of a human being in a cage with monkeys as companions", controversy erupted as black clergymen in the city took great offense. "Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes", said the Reverend James H. Gordon, superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn. "We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls."

New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. refused to meet with the clergymen, drawing the praise of Hornaday, who wrote to him: "When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage."

As the controversy continued, Hornaday remained unapologetic, insisting that his only intention was to put on an ethnological exhibition. In another letter, he said that he and Grant—who ten years later would publish the racist tract The Passing of the Great Race—considered it "imperative that the society should not even seem to be dictated to" by the black clergymen.

1903 saw one of the first widespread protests against human zoos, at the "Human Pavilion" of an exposition in Osaka, Japan. The exhibition of Koreans and Okinawans in "primitive" housing incurred protests from the governments of Korea and Okinawa, and a Formosan woman wearing Chinese dress angered a group of Chinese students studying abroad in Tokyo. An Ainu schoolteacher was made to exhibit himself in the zoo to raise money for his schoolhouse, as the Japanese government refused to pay. The fact that the schoolteacher made eloquent speeches and fundraised for his school while wearing traditional dress confused the spectators. An anonymous front-page column in a Japanese magazine condemned these examples and the "Human Pavilion" in total, calling it inhumane to exhibit people as spectacles.

St. Louis World's Fair

In 1904, over 1,100 Filipinos were displayed at the St. Louis World's Fair in association with the 1904 Summer Olympics. Following the Spanish-American War, the United States had just acquired new territories such as Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. William H. Taft was the civil governor of the Philippines at the time and allowed the U.S. to put together a Philippines exhibition in an attempt to "showcase the new colony." Filipinos were put into villages, known generally by fair attendees as the "Igorrote Village," despite the variety of ethnic groups represented. While the exhibit was promoted as a display of U.S. power and growth, it is believed that to achieve this perspective, the Filipinos themselves were construed as "racially inferior and incapable of national self-determination in the near future." This was done by encouraging the performance of tribal customs that were seen as bizarre and 'savage' by Americans, such as eating dog. The villages also took part in western-influenced demonstrations, such as attending model school and participating in police drill teams.

One of the activities the indigenous people held in the zoo had to participate in were the "Special Olympics." This was an activity decided by the organizers of the zoos at the 1904 world's fair. The people that were kept in the zoos were a symbol for the U.S. latest victory, keeping groups of people in the zoo to look at and showcase their newest territories. Igorot, Negrito, Visayan, and Moro were the four tribes that were brought over from the Philippines to show the diversity of the Filipino people. When originally transported to St. Louis people put in the zoos were originally only given rations of rice, some hardtack, and canned goods. A lot of the Filipinos who arrived came coughing and ill from their travels on the train to St. Louis. They were given temporary live quarters while their traditional huts were being built in the zoo for them to live in during the fair. While being a part of the fair the members of the tribes that were brought to the zoo were made to showcase their unique traditions during the fair to entertain. There was also a school made for the children in these tribes, where visitors could observe from an elevated balcony and view the children learning.

France and Great Britain

Between 1 May and 31 October 1908 the Scottish National Exhibition, opened by one of Queen Victoria's grandsons, Prince Arthur of Connaught, was held in Saughton Park, Edinburgh. One of the attractions was the Senegal Village with its French-speaking Senegalese residents, on show demonstrating their way of life, art and craft while living in beehive huts.

In 1909, the infrastructure of the 1908 Scottish National Exhibition in Edinburgh was used to construct the new Marine Gardens to the coast near Edinburgh at Portobello. A group of Somali men, women and children were shipped over to be part of the exhibition, living in thatched huts.

In 1925, a display at Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester, England, was entitled "Cannibals" and featured black Africans in supposedly native dress.

In 1931, around 100 other New Caledonian Kanaks, were put on display at the Jardin d'Acclimatation in Paris.

United States (1930s)

By the 1930s, a new kind of human zoo appeared in America, nude shows masquerading as education. These included the Zoro Garden Nudist Colony at the Pacific International Exposition in San Diego, California (1935–36) and the Sally Rand Nude Ranch at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco (1939). The former was supposedly a real nudist colony, which used hired performers instead of actual nudists. The latter featured nude women performing in western attire. The Golden Gate fair also featured a "Greenwich Village" show, described in the Official Guide Book as "Model artists' colony and revue theatre."

Ethnological expositions during Nazi Germany

As ethnogenic expositions were discontinued in Germany around 1931, there were many repercussions for the performers. Many of the people brought from their homelands to work in the exhibits had created families in Germany, and there were many children that had been born in Germany. Once they no longer worked in the zoos or for performance acts, these people were stuck living in Germany where they had no rights and were harshly discriminated against. During the rise of the Nazi party, the foreign actors in these stage shows were typically able to stay out of concentration camps because there were so few of them that the Nazis did not see them as a real threat. Although they were able to avoid concentration camps, they were not able to participate in German life as citizens of ethnically German origin could. The Hitler Youth did not allow children of foreign parents to participate, and adults were rejected as German soldiers. Many ended up working in war industry factories or foreign laborer camps. After World War II ended, racism in Germany became more concealed or invisible, but it did not go away. Many people of foreign descent intended to leave after the war, but because of their German nationality, it was difficult for them to emigrate.

Modern exhibitions

As part of the Portuguese World Exhibition in 1940, members of a tribe from the Bissagos Islands of Guinea-Bissau were displayed on an island in a lake in the Lisbon Tropical Botanical Garden.

A Congolese village was displayed at the Brussels 1958 World's Fair.

In April 1994, an example of an Ivory Coast village was presented as part of an African safari in Port-Saint-Père, near Nantes, in France, later called Planète Sauvage.

In July 2005, the Augsburg Zoo in Germany hosted an "African village" featuring African crafts and African cultural performances. The event was subject to widespread criticism. Defenders of the event argued that it was not racist since it did not involve exhibiting Africans in a debasing way, as had been done at zoos in the past. Critics argued that presenting African culture in the context of a zoo contributed to exoticizing and stereotyping Africans, thus laying the ground work for racial discrimination.

In August 2005, London Zoo displayed four human volunteers wearing fig leaves (and bathing suits) for four days.

In 2007, Adelaide Zoo ran a Human Zoo exhibition which consisted of a group of people who, as part of a study exercise, had applied to be housed in the former ape enclosure by day, but then returned home by night. The inhabitants took part in several exercises, and spectators were asked for donations towards a new ape enclosure.

Also in 2007, pygmy performers at the Festival of Pan-African Music (Fespam) were housed at a zoo in Brazzaville, Congo. Although members of the group of 20 people—among them an infant, age three months—were not officially on display, it was necessary for them to "collect firewood in the zoo to cook their food, and [they] were being stared at and filmed by tourists and passers-by".

In 2012, a video surfaced showing a safari trip to the Bay of Bengal. The safari trip included showcasing the Jarawa tribe of the Andaman Islands in their own home. This indigenous tribe had not had much contact with outsiders, and some were asked to perform dances for the tourists. At the beginning of the safari trip there were signs stating not to "feed" the tribespeople, but tourists still brought food to give to the tribespeople. In 2013, the Indian Supreme Court banned these safari trips.

In August 2014, as part of the Edinburgh International Festival, South African theatre-maker Brett Bailey's show Exhibit B was performed in the Playfair Library Hall, University of Edinburgh; then in September at The Barbican in London. This explored the nature of Human Zoos and raised much controversy both amongst the performers and the audiences.

With a view to tackling the morality of Human Zoo exhibits, 2018 saw the poster exhibition, Putting People on Display, tour Glasgow School of Art, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Stirling, the University of St Andrews and the University of Aberdeen. Additional posters were added to a selection from the French ACHAC's exhibition, Human Zoos: the Invention of the Savage, in relation to the Scottish dimension in hosting such shows.

Human safari

The threatening, exploitative and degrading practice of "human safari" tourism has been a prevalent problem particularly for indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation, such as the Sentinelese.