Generative grammar, or generativism /ˈdʒɛnərətɪvɪzəm/, is a linguistic theory that regards linguistics as the study of a hypothesised innate grammatical structure. It is a biological or biologistic modification of earlier structuralist theories of linguistics, deriving from logical syntax and glossematics. Generative grammar considers grammar as a system of rules that generates exactly those combinations of words that form grammatical sentences in a given language. It is a system of explicit rules that may apply repeatedly to generate an indefinite number of sentences which can be as long as one wants them to be. The difference from structural and functional models is that the object is base-generated within the verb phrase in generative grammar. This purportedly cognitive structure is thought of as being a part of a universal grammar, a syntactic structure which is caused by a genetic mutation in humans.

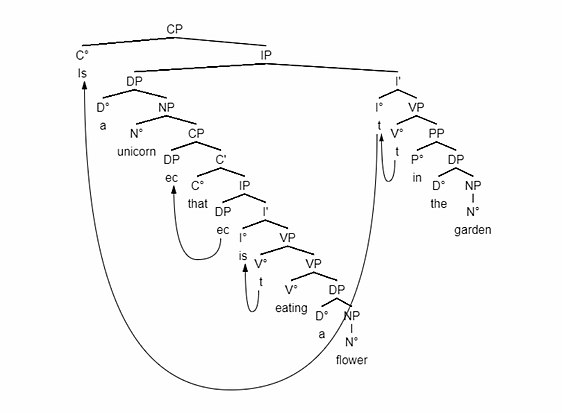

Generativists have created numerous theories to make the NP VP (NP) analysis work in natural language description. That is, the subject and the verb phrase appearing as independent constituents, and the object placed within the verb phrase. A main point of interest remains in how to appropriately analyse Wh-movement and other cases where the subject appears to separate the verb from the object. Although claimed by generativists as a cognitively real structure, neuroscience has found no evidence for it. In other words, generative grammar encompasses proposed models of linguistic cognition; but there is still no specific indication that these are quite correct. Recent arguments have been made that the success of large language models undermine key claims of generative syntax because they are based on markedly different assumptions, including gradient probability and memorized constructions, and out-perform generative theories both in syntactic structure and in integration with cognition and neuroscience.

Frameworks

There are a number of different approaches to generative grammar. Common to all is the effort to come up with a set of rules or principles that formally defines each and every one of the members of the set of well-formed expressions of a natural language. The term generative grammar has been associated with at least the following schools of linguistics:

- Transformational grammar (TG)

- Standard theory (ST)

- Extended standard theory (EST)

- Revised extended standard theory (REST)

- Principles and parameters theory (P&P)

- Monostratal (or non-transformational) grammars

Historical development of models of transformational grammar

Leonard Bloomfield, an influential linguist in the American Structuralist tradition, saw the ancient Indian grammarian Pāṇini as an antecedent of structuralism. However, in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, Chomsky writes that "even Panini's grammar can be interpreted as a fragment of such a 'generative grammar'", a view that he reiterated in an award acceptance speech delivered in India in 2001, where he claimed that "the first 'generative grammar' in something like the modern sense is Panini's grammar of Sanskrit".

Military funding to generativist research was influential to its early success in the 1960s.

Generative grammar has been under development since the mid 1950s, and has undergone many changes in the types of rules and representations that are used to predict grammaticality. In tracing the historical development of ideas within generative grammar, it is useful to refer to the various stages in the development of the theory:

Standard theory (1956–1965)

The so-called standard theory corresponds to the original model of generative grammar laid out by Chomsky in 1965.

A core aspect of standard theory is the distinction between two different representations of a sentence, called deep structure and surface structure. The two representations are linked to each other by transformational grammar.

Extended standard theory (1965–1973)

The so-called extended standard theory was formulated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Features are:

- syntactic constraints

- generalized phrase structures (X-bar theory)

Revised extended standard theory (1973–1976)

The so-called revised extended standard theory was formulated between 1973 and 1976. It contains

- restrictions upon X-bar theory (Jackendoff (1977)).

- assumption of the complementizer position.

- Move α

Relational grammar (ca. 1975–1990)

An alternative model of syntax based on the idea that notions like subject, direct object, and indirect object play a primary role in grammar.

Government and binding/principles and parameters theory (1981–1990)

Chomsky's Lectures on Government and Binding (1981) and Barriers (1986).

Minimalist program (1990–present)

The minimalist program is a line of inquiry that hypothesizes that the human language faculty is optimal, containing only what is necessary to meet humans' physical and communicative needs, and seeks to identify the necessary properties of such a system. It was proposed by Chomsky in 1993.

Context-free grammars

Generative grammars can be described and compared with the aid of the Chomsky hierarchy (proposed by Chomsky in the 1950s). This sets out a series of types of formal grammars with increasing expressive power. Among the simplest types are the regular grammars (type 3); Chomsky argues that these are not adequate as models for human language, because of the allowance of the center-embedding of strings within strings, in all natural human languages.

At a higher level of complexity are the context-free grammars (type 2). The derivation of a sentence by such a grammar can be depicted as a derivation tree. Linguists working within generative grammar often view such trees as a primary object of study. According to this view, a sentence is not merely a string of words. Instead, adjacent words are combined into constituents, which can then be further combined with other words or constituents to create a hierarchical tree-structure.

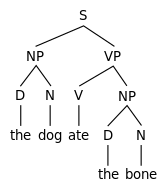

The derivation of a simple tree-structure for the sentence "the dog ate the bone" proceeds as follows. The determiner the and noun dog combine to create the noun phrase the dog. A second noun phrase the bone is created with determiner the and noun bone. The verb ate combines with the second noun phrase, the bone, to create the verb phrase ate the bone. Finally, the first noun phrase, the dog, combines with the verb phrase, ate the bone, to complete the sentence: the dog ate the bone. The following tree diagram illustrates this derivation and the resulting structure:

Such a tree diagram is also called a phrase marker.

They can be represented more conveniently in text form, (though the

result is less easy to read); in this format the above sentence would be

rendered as:

[S [NP [D The ] [N dog ] ] [VP [V ate ] [NP [D the ] [N bone ] ] ] ]

Chomsky has argued that phrase structure grammars are also inadequate for describing natural languages, and formulated the more complex system of transformational grammar.

Evidentiality

Noam Chomsky, the main proponent of generative grammar, believed he had found linguistic evidence that syntactic structures are not learned but "acquired" by the child from universal grammar. This led to the establishment of the poverty of the stimulus argument in the 1980s. However, critics claimed Chomsky's linguistic analysis had been inadequate. Linguistic studies had been made to prove that children have innate knowledge of grammar that they could not have learned. For example, it was shown that a child acquiring English knows how to differentiate between the place of the verb in main clauses from the place of the verb in relative clauses. In the experiment, children were asked to turn a declarative sentence with a relative clause into an interrogative sentence. Against the expectations of the researchers, the children did not move the verb in the relative clause to its sentence initial position, but to the main clause initial position, as is grammatical. Critics however pointed out that this was not evidence for the poverty of the stimulus because the underlying structures that children were proved to be able to manipulate were actually highly common in children's literature and everyday language. This led to a heated debate which resulted in the rejection of generative grammar from mainstream psycholinguistics and applied linguistics around 2000. In the aftermath, some professionals argued that decades of research had been wasted due to generative grammar, an approach which has failed to make a lasting impact on the field.

There is no evidence that syntactic structures are innate. While some hopes were raised at the discovery of the FOXP2 gene, there is not enough support for the idea that it is 'the grammar gene' or that it had much to do with the relatively recent emergence of syntactical speech.

Neuroscientific studies using ERPs have found no scientific evidence for the claim that human mind processes grammatical objects as if they were placed inside the verb phrase. Instead, brain research has shown that sentence processing is based on the interaction of semantic and syntactic processing. However, since generative grammar is not a theory of neurology, but a theory of psychology, it is completely normal in the field of neurology to find no concreteness of the verb phrase in the brain. In fact, these rules do not exist in our brains, but they do model the external behaviour of the mind. This is why GG claims to be a theory of psychology and is considered to be real cognitively.

Generativists also claim that language is placed inside its own mind module and that there is no interaction between first-language processing and other types of information processing, such as mathematics. This claim is not based on research or the general scientific understanding of how the brain works.

Chomsky has answered the criticism by emphasising that his theories are actually counter-evidential. He however believes it to be a case where the real value of the research is only understood later on, as it was with Galileo.