From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Writing

Writing is a cognitive and social activity involving neuropsychological and physical processes and the use of writing systems to create persistent representations of human language. A system of writing relies on many of the same semantic structures as the language it represents, such as lexicon and syntax, with the added dependency of a system of symbols representing that language's phonology and morphology. Nevertheless, written language may take on characteristics distinctive from any available in spoken language.

The outcome of this activity, also called "writing", and sometimes a "text", is a series of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented linguistic symbols. The interpreter or activator of a text is called a "reader".

Writing systems do not themselves constitute languages (with the debatable exception of computer languages); they are a means of rendering language into a form that can be read and reconstructed by other humans separated by time and/or space. While not all languages use a writing system, those that do can complement and extend the capacities of spoken language by creating durable forms of language that can be transmitted across space (e.g. written correspondence) and stored over time (e.g. libraries or other public records). Writing can also have knowledge-transforming effects, since it allows humans to externalize their thinking in forms that are easier to reflect on, elaborate on, reconsider, and revise.

Tools, materials, and motivations to write

Any instance of writing involves a complex interaction among available tools, intentions, cultural customs, cognitive routines, genres, tacit and explicit knowledge, and the constraints and limitations of the writing system(s) deployed. Inscriptions have been made with fingers, styluses, quills, ink brushes, pencils, pens, and many styles of lithography; surfaces used for these inscriptions include stone tablets, clay tablets, bamboo slats, papyrus, wax tablets, vellum, parchment, paper, copperplate, slate, porcelain, and other enameled surfaces. The Incas used knotted cords known as quipu (or khipu) for keeping records. Countless writing tools and surfaces have been improvised throughout history (as the cases of graffiti, tattooing, and impromptu aides-memoire illustrate).

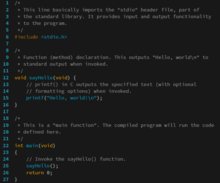

The typewriter and subsequently various digital word processors have recently become widespread writing tools, and studies have compared the ways in which writers have framed the experience of writing with such tools as compared with the pen or pencil. Word processors include, often multi-document, text editors or note-taking apps, Web systems (search engines, Wikis, etc.), messaging software (chat apps, e-mail UIs, etc.), or their underlying operating systems' code supporting the text input device(s).

Advancements in natural language processing and natural language generation allow certain tools (in the form of software) to produce certain kinds of highly formulaic writing (e.g., weather forecasts and brief sports reporting) without the direct involvement of humans after initial configuration or, more commonly, to be used to support writing processes such as generating initial drafts, producing feedback with the help of a rubric, copy-editing, and helping translation.

Writing technologies from different eras coexist easily in many homes and workplaces. During the course of a day or even a single episode of writing, for example, a writer might instinctively switch among a pencil, a touchscreen, a text-editor, a whiteboard, a legal pad, and adhesive notes as different purposes arise.

Motivations and purposes

As human societies emerged, collective motivations for the development of writing were driven by pragmatic exigencies like keeping track of produce and other wealth, recording history, maintaining culture, codifying knowledge through curricula and lists of texts deemed to contain foundational knowledge (e.g., The Canon of Medicine) or to be artistically exceptional (e.g., a literary canon), organizing and governing societies through the formation of legal systems, census records, contracts, deeds of ownership, taxation, trade agreements, treaties, and so on. Amateur historians, including H.G. Wells, had speculated since the early 20th century on the likely correspondence between the emergence of systems of writing and the development of city-states into empires. As Charles Bazerman explains, the "marking of signs on stones, clay, paper, and now digital memories—each more portable and rapidly traveling than the previous—provided means for increasingly coordinated and extended action as well as memory across larger groups of people over time and space." For example, around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration in Mesopotamia outgrew human memory, and writing became a more dependable method for the permanent recording and presentation of transactions. In both ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica, on the other hand, writing may have evolved through calendric and political necessities for recording historical and environmental events. Further innovations included more uniform, predictable, and widely dispersed legal systems, the distribution of accessible versions of sacred texts, and furthering practices of scientific inquiry and knowledge consolidation, all of which were largely reliant on portable and easily reproducible forms of inscribed language. The history of writing is co-extensive with the history of uses of writing and the elaboration of activity systems that give rise to and circulate writing.

Individual, as opposed to collective, motivations for writing include improvised additional capacity for the limitations of human memory (e.g., to-do lists, recipes, reminders, logbooks, maps, the proper sequence for a complicated task or important ritual), dissemination of ideas and coordination (as in an essay, monograph, broadside, plans, (code) issues, petition, or manifesto), imaginative narratives and other forms of storytelling, maintaining kinship and other social networks, negotiating household matters with providers of goods and services and with local and regional governing bodies, and lifewriting (e.g., a diary or journal).

The nearly global spread of digital communication systems such as e-mail and social media has made writing an increasingly important feature of daily life, where these systems mix with older technologies like paper, pencils, whiteboards, printers, and copiers. Substantial amounts of everyday writing characterize most workplaces in developed countries. In many occupations (e.g., law, accounting, software design, human resources, etc.), written documentation is not only the main deliverable but also the mode of work itself. Even in occupations not typically associated with writing, routine workflows (maintaining records, reporting incidents, record-keeping, inventory-tracking, documenting sales, accounting for time, fielding inquiries from clients, etc.) have most employees writing at least some of the time.

The following section offers examples of how writing constitutes much of the labor of many modern careers.

Contemporary uses of writing

Some professions are typically associated with writing, such as literary authors, journalists, and technical writers, but writing is pervasive in most modern forms of work, civic participation, household management, and leisure activities. The following are examples of this pervasiveness, but they are far from encompassing all the uses of writing.

Business and finance

Writing permeates everyday commerce. For example, in the course of an afternoon, a wholesaler might receive a written inquiry about the availability of a product line, then communicate with suppliers and fabricators through work orders and purchase agreements, correspond via email to affirm shipping availability with a drayage company, write an invoice, and request proof of receipt in the form of a written signature. At a much larger scale, modern systems of finances, banking, and business rest on many forms of written documents—including written regulations, policies, and procedures; the creation of reports and other monitoring documents to make, evaluate, and provide accountability for decisions and operations; the creation and maintenance of records; internal written communications within departments to coordinate work; written communications that comprise work products presented to other departments and to clients; and external communications to clients and the public. Business and financial organizations also rely on many written legal documents, such as contracts, reports to government agencies, tax records, and accounting reports. Financial institutions and markets that hold, transmit, trade, insure, or regulate holdings for clients or other institutions are particularly dependent on written records (though now often in digital form) to maintain the integrity of their roles.

Governance and law

Many modern systems of government are organized and sanctified through written constitutions at the national and sometimes state or other organizational levels. Written rules and procedures typically guide the operations of the various branches, departments, and other bodies of government, which regularly produce reports and other documents as work products and to account for their actions. In addition to legislative branches that draft and pass laws, these laws are administered by an executive branch, which can present further written regulations specifying the laws and how they are carried out. Governments at different levels also typically maintain written records on citizens concerning identities, life events such as births, deaths, marriages, and divorces, the granting of licenses for controlled activities, criminal charges, traffic offenses, and other penalties small and large, and tax liability and payments.

Governance systems also produce policies to shape society's activities, sometimes also at the international level, e.g., allocating budgets and regulating or actuating economic mechanisms, ideally towards collective goals and values such as safety and health or addressing identified problems. These also include systems at subnational levels, such as cities and multinational corporations (e.g., corporate governance and Web platform governance).

Written legal codes in modern governments are typically produced by legislative branches and provide standardized rules for commercial, civil, and lawful activity. The legal codes also provide remedies and penalties for violations of the rules, as well as procedures for their enforcement. In the United States, legal proceedings in courts produce written records, which can be appealed based on the written records to higher courts. Written records carry particular evidentiary weight in court proceedings. Lawyers also offer written briefs for initial proceedings, subsequent appeals, and other points at issue; maintain files on the cases they are engaged with; and negotiate written agreements that might resolve cases. Judges produce written opinions that may then be treated as precedent for subsequent cases.

Police departments and other bodies charged with the enforcement of laws and maintenance of civil, commercial, or criminal order regularly must produce reports of the interactions with community members, actions taken, the process and results of inquiries, and the disposition of cases. Such cases are often initiated by written complaints by those alleging injury, thereby opening a file on the case, which then aggregates all the related documents and reports to follow. These files serve as the basis for processing the case, as potential evidence in legal proceedings, and for monitoring and making accountable the working of these departments.

Scientific and scholarly knowledge production

Knowledge produced in research disciplines of the sciences, social sciences, and humanities arises primarily in the form of journal articles and book monographs. Experiments, observational data, archival documents, and other evidence collected as part of research inquiries are then represented within the written contribution and serve as the basis for arguments for new claims intended to be published in specialized academic journals and university presses.

Such data collection and drafting of manuscripts may be supported by grants, which usually require proposals establishing the value of such work and the need for funding. The data and procedures are also typically collected in lab notebooks or other preliminary files. Early versions of the possible publications may also be presented at academic or disciplinary conferences or on publicly accessible web servers to gain peer feedback and build interest in the work. Prior to official publication, these documents are typically read and evaluated by referees from the appropriate research specialties, who, in their written evaluations, determine whether the work is of sufficient value and quality to be published. Referees may also recommend certain improvements be made or that the work not be published.

Publication in such a disciplinary forum does not establish the claims or findings of such work as authoritatively true, only that they are worth the attention of other specialists. Only over time, as others may cite the work (see intertextuality) and use it to advance further claims and the work appears in review articles, handbooks, textbooks, or other aggregations, does it become codified as contingently reliable knowledge.

Scientific or scholarly work written for more popular audiences relies on the published work of the scientific literature for its authority but does not in itself directly contribute to the scientific literature.

Journalism

News and news reporting are central to citizen engagement and knowledge of many spheres of activity people may be interested in about the state of their community, including the actions and integrity of their governments and government officials, economic trends, natural disasters and responses to them, international geopolitical events, including conflicts, but also sports, entertainment, books, and other leisure activities. While news and newspapers have grown rapidly from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, the changing economics and ability to produce and distribute news have brought about radical and rapid challenges to journalism and the consequent organization of citizen knowledge and engagement. These changes have also created challenges for journalism ethics that have been developed over the past century.

Technical and medical writing

Technical and medical writing are recognized writing specialties that, address the needs of scientifically and technologically based professions for precise, accurate, and timely communications, internally and externally, for the audiences the professions serve. Internally, these specialized writers ensure that communications present the necessary information in clear and precise terms to people in various roles. Both in the writing they do, and with the support they provide other professionals within their organizations, they make sure that each person within the organization has the information they need and that the work of the organization is coordinated by making sure all necessary tasks are assigned, and carried out, in a timely and accurate way. Through various media and genres, technical and medical writers elicit the goodwill and cooperation of the public served, while informing the public of the services and products offered, instructions needed for best outcomes, and other information. Technical and medical writers make sure appropriate and accurate records are kept for internal and external accountability and regulation. An important part of their roles is to prepare reports for government approval and monitoring.

Literature and the leisure book market

Works of literature encompass written fiction, poetry, autobiography and memoir, non-fiction, and scripts of dramatic, cinematic or video performance, and hybridized forms of some or all of those previously listed. Works of literature sell widely and encompass a wide substantial market provided by large corporate publishers, self-published writers, and everything in-between. A certain subset of these works gain scholarly attention and are taught in literature classes at schools at all levels, including children's literature, young adult literature, and canonical literature taught at universities; these works typically become the subject of another form of writing: academic scholarship. Other forms of literature that are widely circulated but have only limited scholarly attention include historical fiction, science fiction, romance, fan fiction, western fiction, dystopic and apocalyptic fiction, mystery fiction, fantasy and myth. Other segments of the book market include non-fictional works that some may not characterize as literature but exist within the same marketing space, such as popular history, biography and autobiography, political and celebrity memoirs, self-help and educational books, popular science and technology, accounts of social problems, and futuristic projections.

Authors and publishers' agents produce considerable documentation preparatory and subsequent to the successful publication of literature: prospectuses, developmental editing notes, contracts, correspondence with potential reviewers, press-releases, marketing plans, etc.

Writing within education and educational institutions

Formal education is the social context most strongly associated with the learning of writing, and students may carry these particular associations long after leaving school. Alongside the writing that students read (in the forms of textbooks, assigned books, and other instructional materials as well as self-selected books) students do much writing within schools at all levels, on subject exams, in essays, in taking notes, in doing homework, and in formative and summative assessments. Some of this is explicitly directed toward the learning of writing, but much is focused more on subject learning. Students receive much writing from their teachers as well in the forms of assignments and syllabi, directions for activities, worksheets, corrections on work, or information about subjects or exams. Students also receive institutional notices and regulations, sometimes to be shared with families. Students also may write teacher evaluations for use by teachers to improve instruction or by others reviewing quality of teacher instruction, particularly within higher education.

Writing also pervades schools and educational institutions in less visible and memorable ways. Since schools are typically hierarchically arranged bureaucracies, writing also circulates in the forms of notices and regulations that teachers receive from their supervisors and arrange their instruction according to district and state syllabi and regulations. Teachers often must produce and submit lesson plans or other information about their teaching. In primary and secondary education teachers may need to write notices or letters to parents about matters relating to their children's learning, school activities, or regulations. Within school hierarchies many memos, notices, or other documents may flow. National policies and regulations as elaborated by ministries or departments of education may also be of consequence. Additionally, research in the various subject areas and in educational studies may be attended to by educators in the classroom and higher bureaucratic levels. And of course, subject learning draws on the knowledge produced and authorized by disciplines.

Software code

Hypertext

Other

- Written personal and group communication, using letters, signed texts such as open letters, e-mails, social media and chat software

- Unoriginal writing such as translation of texts and transcription of spoken language

- Screenplay writing for film and other audiovisual scenes.

Writing systems

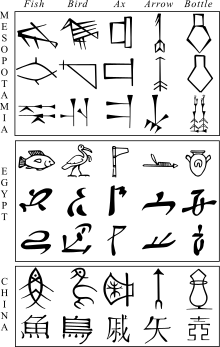

The major writing systems broadly fall into four categories: logographic, syllabic, alphabetic, and featural. As pictograms do not represent a language's sounds, they have been argued not to constitute a writing system.

Logographies

A logography (also called a logosyllabary) is written using logograms—written characters which represent individual words, morphemes or certain syllables. For example, in Mayan, the glyph for "fin", pronounced ka, was also used to represent the syllable ka whenever the pronunciation of a logogram needed to be indicated. Many logograms have an ideographic component (Chinese "radicals", hieroglyphic "determiners"). In Chinese, about 90% of characters are compounds of a semantic (meaning) element called a radical with an existing character to indicate the pronunciation, called a phonetic. However, such phonetic elements complement the logographic elements, rather than vice versa.

The main logographic system in use today is Chinese characters, used with some modification for the various languages or dialects of China, Japan, and sometimes in Korean, although in South and North Korea, the phonetic Hangul system is mainly used. Older logographic systems include cuneiform, and Mayan.

Syllabaries

A syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent syllables, typically a consonant followed by a vowel, or just a vowel alone. In some scripts more complex syllables (such as consonant-vowel-consonant, or consonant-consonant-vowel) may have dedicated glyphs. Phonetically similar syllables are not written similarly. For instance, the syllable "ka" may look nothing like the syllable "ki", nor will syllables with the same vowels be similar.

Syllabaries are best suited to languages with a relatively simple syllable structure, such as Japanese. Other languages that use syllabic writing include the Linear B script for Mycenaean Greek; Cherokee, Ndjuka, an English-based creole language of Suriname; and the Vai script of Liberia.

Alphabets

An alphabet is a set of written symbols that represent consonants and vowels. In a perfectly phonological alphabet, the letters would correspond perfectly to the language's phonemes. Thus, a writer could predict the spelling of a word given its pronunciation, and a speaker could predict the pronunciation of a word given its spelling. However, as languages often evolve independently of their writing systems, and writing systems have been borrowed for languages they were not designed for, the degree to which letters of an alphabet correspond to phonemes of a language varies greatly from one language to another and even within a single language.

Sometimes the term "alphabet" is restricted to systems with separate letters for consonants and vowels, such as the Latin alphabet, although abugidas and abjads may also be accepted as alphabets. Because of this use, Greek is often considered to be the first alphabet.

Abjads

In most of the alphabets of the Middle East, it is usually only the consonants of a word that are written, although vowels may be indicated by the addition of various diacritical marks. Writing systems based primarily on writing just consonants phonemes date back to the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt. Such systems are called abjads, derived from the Arabic word for "alphabet", or consonantaries.

Abugidas

In most of the alphabets of India and Southeast Asia, vowels are indicated through diacritics or modification of the shape of the consonant. These are called abugidas. Some abugidas, such as Ethiopic and Cree, are learned by children as syllabaries, and so are often called "syllabics". However, unlike true syllabaries, there is not an independent glyph for each syllable.

Featural scripts

A featural script represents the features of the phonemes of the language in consistent ways. An example of such a system is Korean hangul. For instance, all labial sounds (pronounced with the lips) may have some element in common. In the Latin alphabet, this is accidentally the case with the letters "b" and "p"; however, labial "m" is completely dissimilar, and the similar-looking "q" and "d" are not labial. In Korean hangul, however, all four labial consonants are based on the same basic element, but in practice, Korean is learned by children as an ordinary alphabet, and the featural elements tend to pass unnoticed.

Another featural script is SignWriting, the most popular writing system for many sign languages, where the shapes and movements of the hands and face are represented iconically. Featural scripts are also common in fictional or invented systems, such as J.R.R. Tolkien's Tengwar.

History and origins

Mesoamerica

A stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing, known as the Cascajal Block, was discovered in the Mexican state of Veracruz and is an example of the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing by approximately 500 years. It is thought to be Olmec.

Of several pre-Columbian scripts in Mesoamerica, the one that appears to have been best developed, and the only one to be deciphered, is the Maya script. The earliest inscription identified as Maya dates to the 3rd century BC. Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing.

Central Asia

In 2001, archaeologists discovered that there was a civilization in Central Asia that used writing c. 2000 BC. An excavation near Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, revealed an inscription on a piece of stone that was used as a stamp seal.

China

The earliest surviving examples of writing in China—inscriptions on so-called "oracle bones", tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae used for divination—date from around 1200 BC in the late Shang dynasty. A small number of bronze inscriptions from the same period have also survived.

In 2003, archaeologists reported discoveries of isolated tortoise-shell carvings dating back to the 7th millennium BC, but whether or not these symbols are related to the characters of the later oracle-bone script is disputed.

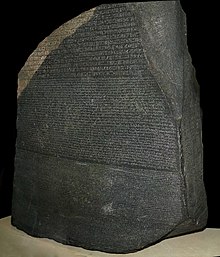

Egypt

The earliest known hieroglyphs are about 5,200 years old, such as the clay labels of a Predynastic ruler called "Scorpion I" (Naqada IIIA period, c. 32nd century BC) recovered at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa'ab) in 1998 or the Narmer Palette, dating to c. 3100 BC, and several recent discoveries that may be slightly older, though these glyphs were based on a much older artistic rather than written tradition. The hieroglyphic script was logographic with phonetic adjuncts that included an effective alphabet. The world's oldest deciphered sentence was found on a seal impression found in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa'ab, which dates from the Second Dynasty (28th or 27th century BC). There are around 800 hieroglyphs dating back to the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom Eras. By the Greco-Roman period, there are more than 5,000.

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this preserved the scribes' status.

The world's oldest known alphabet appears to have been developed by Canaanite turquoise miners in the Sinai desert around the mid-19th century BC. Around 30 crude inscriptions have been found at a mountainous Egyptian mining site known as Serabit el-Khadem. This site was also home to a temple of Hathor, the "Mistress of turquoise". A later, two line inscription has also been found at Wadi el-Hol in Central Egypt. Based on hieroglyphic prototypes, but also including entirely new symbols, each sign apparently stood for a consonant rather than a word: the basis of an alphabetic system. It was not until the 12th to 9th centuries, however, that the alphabet took hold and became widely used.

Elamite scripts

Over the centuries, three distinct Elamite scripts developed. Proto-Elamite is the oldest known writing system from Iran. In use only for a brief time (c. 3200–2900 BC), clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran, with the majority having been excavated at Susa, an ancient city located east of the Tigris and between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers. The Proto-Elamite script is thought to have developed from early cuneiform (proto-cuneiform). The Proto-Elamite script consists of more than 1,000 signs and is thought to be partly logographic.

Linear Elamite is a writing system attested in a few monumental inscriptions in Iran. It was used for a very brief period during the last quarter of the 3rd millennium BC. It is often claimed that Linear Elamite is a syllabic writing system derived from Proto-Elamite, although this cannot be proven since Linear-Elamite has not been deciphered. Several scholars have attempted to decipher the script, most notably Walther Hinz and Piero Meriggi.

The Elamite cuneiform script was used from about 2500 to 331 BC, and was adapted from the Akkadian cuneiform. The Elamite cuneiform script consisted of about 130 symbols, far fewer than most other cuneiform scripts.

Europe

Notational signs from ~37,000 years ago in caves, apparently convey calendaric meaning about the behaviour of animal species drawn next to them, and are considered the first known (proto-)writing in history.

Cretan and Greek scripts

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on artifacts of Crete (early-to-mid-2nd millennium BC, MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). Linear B, the writing system of the Mycenaean Greeks, has been deciphered while Linear A has yet to be deciphered. The sequence and the geographical spread of the three overlapping, but distinct writing systems can be summarized as follows (beginning date refers to first attestations, the assumed origins of all scripts lie further back in the past): Cretan hieroglyphs were used in Crete from c. 1625 to 1500 BC; Linear A was used in the Aegean Islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), and the Greek mainland (Laconia) from c. 18th century to 1450 BC; and Linear B was used in Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) from c. 1375 to 1200 BC.

Indus Valley

Indus script refers to short strings of symbols associated with the Indus Valley Civilization (which spanned modern-day Pakistan and North India) used between 2600-1900 BC. Despite attempts at decipherments and claims, it is as yet undeciphered. The term 'Indus script' is mainly applied to that used in the mature Harappan phase, which perhaps evolved from a few signs found in early Harappa after 3500 BC. The script is written from right to left, and sometimes follows a boustrophedonic style. In 2015, the epigrapher Bryan Wells estimated there were around 694 distinct signs. This is above 400, so scholars accept the script to be logo-syllabic (typically syllabic scripts have about 50–100 signs whereas logographic scripts have a very large number of principal signs). Several scholars maintain that structural analysis indicates an agglutinative language underlies the script.

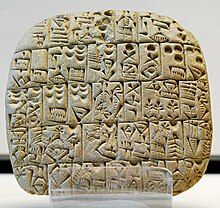

Mesopotamia

While research into the development of writing during the late Stone Age is ongoing, the current consensus is that it first evolved from economic necessity in the ancient Near East. Writing most likely began as a consequence of political expansion in ancient cultures, which needed reliable means for transmitting information, maintaining financial accounts, keeping historical records, and similar activities. Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration outgrew the power of memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form.

The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the emergence of civilisations and the beginning of the Bronze Age of the late 4th millennium BC. The Sumerian archaic cuneiform script and the Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally considered the earliest writing systems, both emerging out of their ancestral proto-literate symbol systems from 3400 to 3300 BC with earliest coherent texts from about 2600 BC. It is generally agreed that Sumerian writing was an independent invention; however, it is debated whether Egyptian writing was developed completely independently of Sumerian, or was a case of cultural diffusion.

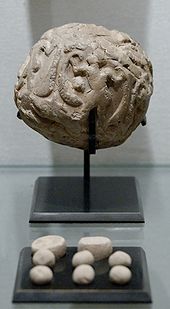

Archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat determined the link between previously uncategorized clay "tokens", the oldest of which have been found in the Zagros region of Iran, and the first known writing, Mesopotamian cuneiform. In approximately 8000 BC, the Mesopotamians began using clay tokens to count their agricultural and manufactured goods. Later they began placing these tokens inside large, hollow clay containers (bulla, or globular envelopes) which were then sealed. The quantity of tokens in each container came to be expressed by impressing, on the container's surface, one picture for each instance of the token inside. They next dispensed with the tokens, relying solely on symbols for the tokens, drawn on clay surfaces. To avoid making a picture for each instance of the same object (for example: 100 pictures of a hat to represent 100 hats), they 'counted' the objects by using various small marks. In this way the Sumerians added "a system for enumerating objects to their incipient system of symbols".

The original Mesopotamian writing system was derived around 3200 BC from this method of keeping accounts. By the end of the 4th millennium BC, the Mesopotamians were using a triangular-shaped stylus pressed into soft clay to record numbers. This system was gradually augmented with using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted by means of pictographs. Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing was gradually replaced by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms, but by the 29th century BC also for phonetic elements. Around 2700 BC, cuneiform began to represent syllables of spoken Sumerian. About that time, Mesopotamian cuneiform became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers. This script was adapted to another Mesopotamian language, the East Semitic Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian) around 2600 BC, and then to others such as Elamite, Hattian, Hurrian and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian. With the adoption of Aramaic as the 'lingua franca' of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC), Old Aramaic was also adapted to Mesopotamian cuneiform. The last cuneiform scripts in Akkadian discovered thus far date from the 1st century AD.

Phoenician writing system and descendants

The Proto-Sinaitic script, in which Proto-Canaanite is believed to have been first written, is attested as far back as the 19th century BC. The Phoenician writing system was adapted from the Proto-Canaanite script sometime before the 14th century BC, which in turn borrowed principles of representing phonetic information from Egyptian hieroglyphs. This writing system was an odd sort of syllabary in which only consonants are represented. This script was adapted by the Greeks, who adapted certain consonantal signs to represent their vowels. The Cumae alphabet, a variant of the early Greek alphabet, gave rise to the Etruscan alphabet and its own descendants, such as the Latin alphabet and Runes. Other descendants from the Greek alphabet include Cyrillic, used to write Bulgarian, Russian and Serbian, among others. The Phoenician system was also adapted into the Aramaic script, from which the Hebrew and the Arabic scripts are descended.

The Tifinagh script (Berber languages) is descended from the Libyco-Berber script, which is assumed to be of Phoenician origin.

Religious texts

In the history of writing, religious texts or writing have played a special role. For example, some religious text compilations have been some of the earliest popular texts, or even the only written texts in some languages, and in some cases are still highly popular around the world. The first books printed widely using the printing press were bibles. Such texts enabled rapid spread and maintenance of societal cohesion, collective identity, motivations, justifications and beliefs that e.g. notably historically supported or enabled large-scale warfare between modern humans.

Contemporary efforts to foster writing acquisition

Multiple programs are in place to aid both children and adults in improving their literacy skills. For example, the emergence of the writing center and community-wide literacy councils aim to help students and community members sharpen their writing skills. These resources, and many more, span across different age groups in order to offer each individual a better understanding of their language and how to express themselves via writing in order to perhaps improve their socioeconomic status. As William J. Farrell puts it: "Did you ever notice that, when people become serious about communication, they want it in writing?"

Other parts of the world have seen an increase in writing abilities as a result of programs such as the World Literacy Foundation and International Literacy Foundation, as well as a general push for increased global communication.