In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal device to indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of the Germanic languages, where scholars use the term 'alliterative poetry' rather broadly to indicate a tradition which not only shares alliteration as its primary ornament but also certain metrical characteristics. The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, the Old Norse Poetic Edda, and many Middle English poems such as Piers Plowman, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Layamon's Brut and the Alliterative Morte Arthur all use alliterative verse.

While alliteration is common in many poetic traditions, it is 'relatively infrequent' as a structured characteristic of poetic form. However, structural alliteration appears in a variety of poetic traditions, including Old Irish, Welsh, Somali and Mongol poetry. The extensive use of alliteration in the so-called Kalevala meter, or runic song, of the Finnic languages provides a close comparison, and may derive directly from Germanic-language alliterative verse.

Unlike in other Germanic languages, where alliterative verse has largely fallen out of use (except for deliberate revivals, like Richard Wagner's 19th-century German Ring Cycle), alliteration has remained a vital feature of Icelandic poetry. After the 14th Century, Icelandic alliterative poetry mostly consisted of rímur, a verse form which combines alliteration with rhyme. The most common alliterative ríma form is ferskeytt, a kind of quatrain. Examples of rimur include Disneyrímur by Þórarinn Eldjárn, ''Unndórs rímur'' by an anonymous author, and the rimur transformed to post-rock anthems by Sigur Ros. From 19th century poets like Jonas Halgrimsson to 21st-century poets like Valdimar Tómasson, alliteration has remained a prominent feature of modern Icelandic literature, though contemporary Icelandic poets vary in their adherence to traditional forms.

By the early 19th century, alliterative verse in Finnish was largely restricted to traditional, largely rural folksongs, until Elias Lönnrot and his compatriots collected them and published them as the Kalevala, which rapidly became the national epic of Finland and contributed to the Finnish independence movement. This led to poems in Kalevala meter becoming a significant element in Finnish literature and popular culture.

Alliterative verse has also been revived in Modern English. Many modern authors include alliterative verse among their compositions, including Poul Anderson, W.H. Auden, Fred Chappell, Richard Eberhart, John Heath-Stubbs, C. Day-Lewis, C. S. Lewis, Ezra Pound, John Myers Myers, Patrick Rothfuss, L. Sprague de Camp, J. R. R. Tolkien and Richard Wilbur. Modern English alliterative verse covers a wide range of styles and forms, ranging from poems in strict Old English or Old Norse meters, to highly alliterative free verse that uses strong-stress alliteration to connect adjacent phrases without strictly linking alliteration to line structure. While alliterative verse is relatively popular in the speculative fiction (specifically, the speculative poetry) community, and is regularly featured at events sponsored by the Society for Creative Anachronism, it also appears in poetry collections published by a wide range of practicing poets.

Common Germanic origins

The poetic forms found in the various Germanic languages are not identical, but there is still sufficient similarity to make it clear that they are closely related traditions, stemming from a common Germanic source. Knowledge about that common tradition, however, is based almost entirely on inference from later poetry.

Originally all alliterative poetry was composed and transmitted orally, and much went unrecorded. The degree to which writing may have altered this oral art form remains much in dispute. Nevertheless, there is a broad consensus among scholars that the written verse retains many (and some would argue almost all) of the features of the spoken language.

One statement we have about the nature of alliterative verse from a practicing alliterative poet is that of Snorri Sturluson in the Prose Edda. He describes metrical patterns and poetic devices used by skaldic poets around the year 1200. Snorri's description has served as the starting point for scholars to reconstruct alliterative meters beyond those of Old Norse.

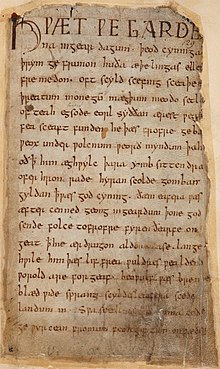

Alliterative verse has been found in some of the earliest monuments of Germanic literature. The Golden Horns of Gallehus, discovered in Denmark and likely dating to the 4th century, bear this Runic inscription in Proto-Norse:

x / x x x / x x / x / x x ek hlewagastiʀ holtijaʀ || horna tawidō (I, Hlewagastiʀ [son?] of Holt, made the horn.)

This inscription contains four strongly stressed syllables, the first three of which alliterate on ⟨h⟩ /x/ and the last of which does not alliterate, essentially the same pattern found in much later verse.

Formal Features

Meter and Rhythm

The core metrical features of traditional Germanic alliterative verse are as follows; they can be seen in the Gallehus inscription above:

- A long line is divided into two half-lines. Half-lines are also known as 'verses', 'hemistiches', or 'distiches'; the first is called the 'a-verse' (or 'on-verse'), the second the 'b-verse' (or 'off-verse'). The rhythm of the b-verse is generally more regular than that of the a-verse, helping listeners to perceive where the end of the line falls.

- A heavy pause, or 'cæsura', separates the verses.

- Each verse usually has two heavily stressed syllables, referred to as 'lifts' or 'beats' (other, less heavily stressed syllables, are called 'dips').

- The first and/or second lift in the a-verse alliterates with the first lift in the b-verse.

- The second lift in the b-verse does not alliterate with the first lifts.

Some of these fundamental rules varied in certain traditions over time. For example, in Old English alliterative verse, in some lines the second but not the first lift in the a-verse alliterated with the first lift in the b-verse, for instance line 38 of Beowulf (ne hyrde ic cymlicor ceol gegyrwan).

Unlike in post-medieval English accentual verse, in which a syllable is either stressed or unstressed, Germanic poets were sensitive to degrees of stress. These can be thought of at three levels:

- most stressed ('stress-words'): root syllables of nouns, adjectives, participles, infinitives

- less stressed ('particles'): root syllables of most finite verbs (i.e. tensed verbs) and adverbs

- even less stressed ('proclitics'): most pronouns, weakly stressed adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, parts of the verb to be, word-endings

If a half-line contains one or more stress-words, their root syllables will be the lifts. (This is the case in the Gallehus Horn inscription above, where all the lifts are nouns.) If it contains no stress-words, the root syllables of any particles will be the lift. Rarely, even a proclitic can be the lift, either because there are no more heavily stressed syllables or because it is given extra stress for some particular reason.

Lifts also have to meet an additional requirement, involving what linguists term quantity, which is related to vowel length. A syllable like the li in little, which ends in a short vowel, takes less time to say than a syllable like the ow in growing, which ends in a long vowel or a diphthong. A closed syllable, which ends with one or more consonants, like bird, takes about the same amount of time as a long vowel. In the older Germanic languages, a syllable ending with a short vowel could not be one of the three potentially alliterating lifts by itself. Instead, if a lift was occupied by word with a short root vowel followed by only one consonant followed by an unstressed vowel (i.e. '(-)CVCV(-)) these two syllables were in most circumstances counted as only one syllable. This is called resolution.

The patterns of unstressed syllables vary significantly in the alliterative traditions of different Germanic languages. The rules for these patterns remain imperfectly understood and subject to debate.

Rules for alliteration

Alliteration fits naturally with the prosodic patterns of early Germanic languages. Alliteration essentially involves matching the left edges of stressed syllables. Early Germanic languages share a left-prominent prosodic pattern. In other words, stress falls on the root syllable of a word, which is normally the initial syllable (except where the root is preceded by an unstressed prefix, as in past participles, for example). This means that the first sound of a word was particularly salient to listeners. Traditional Germanic verse had two particular rules about alliteration:

- All vowels alliterate with each other. The precise reasons for this are debated. The most common, but not uniformly accepted, theory for vowel-alliteration is that words beginning with vowels all actually began with a glottal stop (as is still the case in some modern Germanic languages).

- The consonant clusters st-, sp- and sc- are treated as separate sounds (so st- only alliterates with st-, not with s- or sp-).

Diction

The need to find an appropriate alliterating word gave certain other distinctive features to alliterative verse as well. Alliterative poets drew on a specialized vocabulary of poetic synonyms rarely used in prose texts and used standard images and metaphors called kennings.

Old Saxon and medieval English attest to the word fitt with the sense of 'a section in a longer poem', and this term is sometimes used today by scholars to refer to sections of alliterative poems.

Relationship with Kalevala meter

The trochaic tetrametrical meter that characterises the traditional poetry of most Finnic-language cultures, known as Kalevala meter, does not deploy alliteration with the structural regularity of Germanic-language alliterative verse, but Kalevala meter does have a very strong convention that, in each line, two lexically stressed syllables should alliterate. In view of the profound influence of the Germanic languages on other aspects of the Finnic languages and the unusualness of such regular requirements for alliteration, it has been argued that Kalevala meter borrowed both its use of alliteration and possibly other metrical features from Germanic.

Comparison to Other Alliterative Traditions

Germanic alliterative verse is not the only alliterative verse tradition. It is thus worthwhile briefly to compare Germanic alliterative verse with other alliterative verse traditions, such as Somali and Mongol poetry. Like German alliterative verse, Somali alliterative verse is built around short lines (phrasal units, roughly equal in size to the Germanic half-line) whose strongest stress must alliterate with the strongest stress in another phrase. However, in traditional Somali alliterative verse, alliterating consonants are always word-initial, and the same alliterating consonant must carry through across multiple successive lines within a poem. In Mongol alliterative verse, individual lines are also phrases, with strongest stress on the first word of the phrase. Lines are grouped into pairs, often parallel in structure, which must alliterate with one another, though alliteration between the head-stress and later words in the line is also allowed, and non-identical alliteration (for example, of voiced and voiceless consonants) is also accepted. Like Germanic alliterative verse, Somali and Mongol verse both emerge from oral traditions. Mongol poetry, but not Somali poetry, resembles Germanic verse in its emphasis on heroic epic.

Old High German and Old Saxon

Available Texts

The Old High German and Old Saxon corpus of Stabreim or alliterative verse is small. Fewer than 200 Old High German lines survive, in four works: the Hildebrandslied, Muspilli, the Merseburg Charms and the Wessobrunn Prayer. All four are preserved in forms that are clearly to some extent corrupt, suggesting that the scribes may themselves not have been entirely familiar with the poetic tradition. Two Old Saxon alliterative poems survive. One is the reworking of the four gospels into the epic Heliand (nearly 6000 lines), where Jesus and his disciples are portrayed in a Saxon warrior culture. The other is the fragmentary Genesis (337 lines in 3 unconnected fragments), created as a reworking of Biblical content based on Latin sources.

In more recent times, Richard Wagner sought to evoke these old German models and what he considered a more natural and less over-civilised style by writing his Ring poems in Stabreim.

Formal Features

Both German traditions show one common feature which is much less common elsewhere: a proliferation of unaccented syllables. Generally these are parts of speech which would naturally be unstressed — pronouns, prepositions, articles, modal auxiliaries — but in the Old Saxon works there are also adjectives and lexical verbs. The unaccented syllables typically occur before the first stress in the half-line, and most often in the b-verse.

The Hildebrandslied, lines 4–5:

Garutun se iro guðhamun, gurtun sih iro suert ana, |

They prepared their fighting outfits, girded their swords on, |

The Heliand, line 3062: Sâlig bist thu Sîmon, quað he, sunu Ionases; ni mahtes thu that selbo gehuggean blessed are you Simon, he said, son of Jonah; for you did not see that yourself (Matthew 16, 17)

This leads to a less dense style, no doubt closer to everyday language, which has been interpreted both as a sign of decadent technique from ill-tutored poets and as an artistic innovation giving scope for additional poetic effects. Either way, it signifies a break with the strict Sievers typology.

Old Norse and Icelandic

Types of Old Norse Alliterative Verse

Essentially all Old Norse poetry was written in some form of alliterative verse. It falls into two main categories: Eddaic and Skaldic poetry. Eddaic poetry was anonymous, originally orally transmitted, and mostly consisted or legends, mythological stories, wise sayings and proverbs. A majority of the Eddaic poetry appears in the Poetic Edda, a manuscript traditionally attributed to Snorri Sturlison. Skaldic poetry was associated with individual poets or skalds, typically employed by a king or other ruler, who primarily wrote poems praising their patron or criticizing their patron's enemies. It thus tends to be more elaborate and poetically ambitious than Eddaic poetry.

Formal Features

The inherited form of alliterative verse was modified somewhat in Old Norse poetry. In Old Norse, as a result of phonetic changes from the original common Germanic language, many unstressed syllables were lost. This lent Old Norse verse a characteristic terseness; the lifts tended to be crowded together at the expense of the weak syllables. In some lines, the weak syllables have been entirely suppressed. As a result, while we still have the base pattern of paired half-lines joined by alliteration, it is very rare to have multiple-syllable dips. The following example from the Hávamál illustrates this basic pattern:

Deyr fé |

Cattle die; |

Meter and Rhythm

The terseness of the Norse form may be linked to another feature of Norse poetry that differentiates it from common Germanic patterns: In Old Norse poetry, syllable count sometimes matters, and not just the number of lifts and dips. That depends upon the specific verse form used, of which Old Norse poetry had many. The base, Common Germanic alliterative meter is what Old Norse poets termed fornyrðislag ("old story meter"). More complex verse forms imposed an extra layer of structure in which syllable count, stress, alliteration (and sometimes, assonance and rhyme) worked together to define line or stanza structures. For example, in kviðuhattr ("lay form"), the first half line had to contain four, and the second half-line, three syllables, while in ljóðaháttr ("song" or "ballad" meter), there were no specific syllable counts, but the lines were arranged into four-line stanzas alternating between four- and three-lift lines. More complex stanza forms imposed additional constraints. The various names of the Old Norse verse forms are given in the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. The Háttatal, or "list of verse forms", contains the names and characteristics of each of the fixed forms of Norse poetry.

Rules for Alliteration

Old Norse followed the general Germanic rules for alliteration, but imposed specific alliteration patterns on specific verse forms, and sometimes rules for assonance and internal rhyme. For example, drottkvætt ("courtly meter") not only required alliteration between adjacent half-lines, but imposed requirements for consonance and internal rhyme at specific points in each stanza.

Diction

Old Norse was rich in poetic synonyms and kennings, where it closely resembled Old English. Norse poets were sometimes described as creating "riddling" kennings whose meaning was not necessarily self-evident to the audience, perhaps reflecting competition among skalds.

An Example

The following poem from Egil's Saga illustrates the basic principles of Old Norse alliterative verse. For convenience, the 'b' verses (the lines containing the critical last alliteration in the line, or headstave) are indented and alliterating consonants are bolded and underlined.

Nús hersis hefnd |

'For a noble warrior slain |

Further details about Old Norse versification can be found in the companion article, Old Norse Poetry.

Icelandic

Icelandic is not only descended from Old Norse, it is so conservative that Old Norse literature is still read in Iceland. Traditional Icelandic poetry, however, follows somewhat different rules than Old Norse, both for rhythm and alliteration. The following brief description captures the basic rules of modern Icelandic alliterative verse, which was the dominant form of Icelandic poetry until recent decades, and is still a living cultural tradition.

Formal Features

Meter, Rhythm, and Alliteration

Icelandic alliterative verse contains lines that typically contain eight to ten syllables. They are traditionally analyzed into feet, one per stress, with typically falling rhythm. The first foot in a line is considered a heavy foot, the second, a light foot, and so on, with the third and fifth foot counting as heavy, and the second and fourth as light. Icelandic lines are basically Germanic half-lines; they come in pairs. The head-stave is the first stressed syllable in the second line in each pair, which must alliterate with at least one stress in the preceding line. The alliterating stresses in the first line in each pair are called props, or studlar, following the usual Germanic rules about which consonants alliterate. They are subject to the following rules:

- at least one prop must stand in a heavy foot

- if both props are in heavy feet, no more than one light foot can separate them.

- A prop can only appear in a light foot if it is immediately adjacent to a prop in a heavy foot.

- If the second prop appears in a light foot, only one foot can separate it from the head-stave in the next line

- If the second prop appears in a heavy foot, one or two feet can separate it from the head-stave in the next line.

This system allows considerable rhythmic flexibility.

Icelandic keeps some Old Norse forms, such as fornyrðislag, ljóðaháttur, and dróttkvætt. It also has a wide variety of stanzaic forms that combine the alliterative structure described above with rhyme (rimur), including quatrain structures like ferskeytla that rhyme ABAB, couplet structures (stafhenduætt), tercet structures like baksneidd braghenda, and longer patterns, in which rhyming and alliteration patterns run either in parallel or in counterpoint.

Diction

Traditional poetic synonyms and kennings persisted in Icelandic rimur as late as the 18th Century, but were criticized by modernizing poets such as Jonas Hallgrimsson, and dropped out of later usage.

An Example

The following poem in kviðuhattr meter by Jónas Hallgrímsson with translation by Dick Ringler illustrates how the rules for Icelandic alliterative verse work. For convenience, lines starting with a head stave are indented and both props and headstave are bolded and underlined.

Íslands minni |

A Toast to Iceland |

Recent Developments

Alliterative verse appears to have been the dominant poetic tradition in Iceland until well after World War II. In the last generation, or so, a split appears to have developed between avant garde and traditionalist approaches to Icelandic poetry, with alliteration remaining frequent in all forms of Icelandic poetry, but playing a structural, defining role only in more traditional forms.

Old English

Old English classical poetry, epitomised by Beowulf, follows the rules of traditional Germanic poetry outlined above, and is indeed a major source for reconstructing them. J.R.R. Tolkien's essay "On Translating Beowulf" analyses the rules as used in the poem. Old English poetry, even after the introduction of Christianity, was uniformly written in alliterative verse, and much of the literature written in Old English, such as the Dream of the Rood, is explicitly Christian, though poems like Beowulf demonstrate continuing cultural memory for the Pagan past. Alliterative verse was so strongly entrenched in Old English society that English monks, writing in Latin, would sometimes create Latin approximations to alliterative verse.

Types of Old English Alliterative Verse

Old English alliterative verse comes in a variety of forms. It includes heroic poetry like Beowulf, The Battle of Brunanburh, or The Battle of Maldon; elegiac or "wisdom" Poetry like The Ruin or The Wanderer, riddles, translations of classical and Latin poetry, saints' lives, poetic Biblical paraphrases, original Christian poems, charms, mnemonic poems used to memorize information, and the like.

Formal Features

Meter and Rhythm

As described above for the Germanic tradition as a whole, each line of poetry in Old English consists of two half-lines or verses with a pause or caesura in the middle of the line. Each half-line usually has two accented syllables, although the first may only have one. The following example from the poem The Battle of Maldon, spoken by the warrior Beorhtwold, shows the usual pattern:

Hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cēnre, |

Will must be the harder, courage the bolder, |

Note the single alliteration per half-line in the third line. Clear indications of Modern English meanings can be heard in the original, using phonetic approximations of the Old English sound-letter system:

- High [courage] shall the harder, heart the keener,

- mood shall the more, as our main [might] littleth

- here lies our elder all for-heaved

Single 'half-lines' are sometimes found in Old English verse; scholars debate how far these were a characteristic of Old English poetic tradition and how far they arise from defective copying of poems by scribes.

Rules for alliteration

Old English follows the general rules for Germanic alliteration. The first stressed syllable of the off-verse, or second half-line, usually alliterates with one or both of the stressed syllables of the on-verse, or first half-line. The second stressed syllable of the off-verse does not usually alliterate with the others. Note that Old English only requires one alliteration in each half-line, unlike Middle English, which normally requires both lifts in the on-verse to be alliterated.

Diction

Old English was rich in poetic synonyms and kennings. For instance, the Old English poet could deploy a wide array of synonyms and kennings to refer to the sea: sæ, mere, deop wæter, seat wæter, hæf, geofon, windgeard, yða ful, wæteres hrycg, garsecg, holm, wægholm, brim, sund, floð, ganotes bæð, swanrad, seglrad, among others. This ranges from synonyms surviving in English, like sea and mere, to rarer poetic words and compounds, to full-on kennings like "gannet's bath", "whale-road", or "seal-road".

Further details about Old English versification can be found in the companion article, Old English Meter.

The Middle English "Alliterative Revival"

Just as rhyme was seen in some Anglo-Saxon poems (e.g. The Rhyming Poem, and, to some degree, The Proverbs of Alfred), the use of alliterative verse continued (or was revived) in Middle English, though which it was—continuation, or revival—is a matter of some debate. Layamon's Brut, written in about 1215, uses what seems like a loose alliterative meter in comparison with pre-Conquest alliterative verse. Starting in the mid-14th century, alliterative verse became popular in the English North, the West Midlands, and a little later in Scotland. The Pearl Poet uses a complex scheme of alliteration, rhyme, and iambic metre in his Pearl; a more conventional alliterative metre in Cleanness and Patience, and alliterative verse alternating with rhymed quatrains in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. William Langland's Piers Plowman is another important English alliterative poem; it was written between c. 1370 and 1390.

Historical Context

The survival—or revival—of alliterative verse in 14th Century England makes it, like Iceland, an outlier in medieval Christian culture, which came to be dominated by Latin and Romance verse forms and literary traditions. Alliterative verse in post-Conquest England had to compete with imported, often French-derived forms in rhyming stanzas, reflecting what must have seemed like the common practice of the rest of Christendom. Despite these disadvantages, alliterative verse became the preferred English meter for historical romances, especially those concerned with the so-called Arthurian "Matter of Britain", and to be a common mode for political protest, through Piers Plowman and a variety of allegories, satires, and political prophesies. However, as with Icelandic rimur, many 14th-Century poems combine alliteration with rhyming stanzas. Increasingly, however, the alliterative verse tradition was marginalized relative to other English verse traditions, most notably the metrical, rhyming tradition associated with Geoffrey Chaucer.

Types of Middle English Alliterative Verse

Middle English (and Scots) alliterative verse fell into several typical categories. There were the Arthurian romances, such as Layamon's Brut, the Alliterative Morte Arthur, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Awyntyrs off Arthure, The Avowing of Arthur, Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle, The Knightly Tale of Gologras and Gawain, and Charlemagne and Ralph the Collier. There were accounts of warfare, like the Siege of Jerusalem and Scotish Feilde. There were poems devoted to Biblical stories, Christian virtues, and religious allegory, and religious instruction, like Cleanness, Patience, Pearl, The Three Dead Kings, The Castle of Perseverance, the York, Chester, and other municipal mystery plays, St. Erkenwald, the Pistil of Swete Susan, or Pater Noster. And there were a variety of poems falling in a space that ranged from allegory to satire to political commentary, including Piers Plowman, Winnere and Wastoure, Mum and the Sothsegger, The Parlement of Three Ages, The Buke of the Howlat, Richard the Redeless, Jack Upland, Friar Daw's Reply, Jack Uplands Rejoinder, The Blacksmiths, The Tournament of Tottenham, Sum Practysis of Medecyne, and The Tretis of the Twa Mariit Women and the Wedo.

Formal Features

Meter and Rhythm

The form of alliterative verse changed gradually over time. Layamon's Brut retained many features of Old English verse, along with significant changes in meter. By the 14th Century, the Middle English alliterative long line had emerged, which was rhythmically very different from the Old English meter. In Old English, the first half-line (the on-verse, or a-verse) was not very different rhythmically from the second half-line (the off-verse, or b-verse). In Middle English, the a-verse had great rhythmic flexibility (so long as it contained two clear strong stresses), whereas the b-verse could only contain one "long dip" (sequence of two or more unstressed or weakly stressed syllables). These rules applied to unrhymed alliterative long lines, typical of longer alliterative poems. Rhyming alliterative poems, such as Pearl and the densely structured poem The Three Dead Kings, were generally built, like later English rhyming verse, on patterns of alternating stresses.

The following lines Piers Plowman illustrate the basic rhythmic patterns of the Middle English alliterative long line:

A feir feld full of folk fond I þer bitwene,

Of alle maner of men, þe mene and þe riche,

Worchinge and wandringe as þe world askeþ.

In modern spelling:

A fair field full of folk found I there between,

Of all manner of men the mean and the rich,

Working and wandering as the world asketh.

In modern translation:

Among them I found a fair field full of people

All manner of men, the poor and the rich

Working and wandering as the world requires.

The 'a' verses contain multiple unstressed or weakly stressed syllables before, between, and after the two main stresses. In the 'b' verses, the long dip falls immediately before or after the first strong stress in that half-line.

Rules for Alliteration

In the Middle-English 'a'-verse, the two main stresses alliterate with one another and with the first stressed syllable in the 'b'-verse. There are thus a minimum of three alliterations in the Middle English long line, a fact that is implicitly recognized by the comment made by the parson in the Parson's Prologue in the Canterbury Tales that he did not know how to "rum, ram, ruf, by letter". In the 'a'-verse, additional, secondary stresses can also alliterate, as seen in the line quoted above from Piers Plowman ('a fair field full of folk', with four alliterations in the 'a'-verse), or in Sir Gawain l.2, "the borgh brittened and brent" with three alliterations in the 'a'-verse). Only the first stress in the 'b'-verse normally alliterates,in line with the general Germanic rule that the last stress in the line does not alliterate. However, in Middle English alliterative poems, the final stress occasionally alliterates with other strong stresses in the line (as in the first line of Piers Plowman: "In a somer seson, whan softe was þe sonne,").

Diction

Middle English alliterative verse maintained a stock of poetic synonyms, many of them inherited from Old English, though it was no longer characterized by the rich use of kennings. For example, a Middle English alliterative poem could refer to men by such a variety of terms as were, churl, shalk, gome, here, rink, segge, freke, man, carman, mother's son, heme, hind, piece, buck, bourne, groom, sire, harlot, guest, tailard, tulk, sergeant, fellow, or horse.

The Death of the Alliterative Tradition

After the fifteenth century, alliterative verse became fairly uncommon; possibly the last major poem in the tradition is William Dunbar's Tretis of the Tua Marriit Wemen and the Wedo (c. 1500). By the middle of the sixteenth century, the four-beat alliterative line had completely vanished, at least from the written tradition: the last poem using the form that has survived, Scotish Feilde, was written in or soon after 1515 for the circle of Thomas Stanley, 2nd Earl of Derby in commemoration of the Battle of Flodden.

The Modern Revival (alliterative verse in contemporary English)

The late 18th and early 19th century rediscovery of the deep past set the stage for the revival of English alliterative verse. In 1786, Sir William, in a speech to the Asiatic Society of Calcutta, demonstrated that Sanskrit, the holy language of India, was related to Latin, Greek, and most of the European languages, which must therefore all be descended from a common ancestor. Between 1780 and 1840, scholars rediscovered long-forgotten manuscripts in monasteries and private libraries, leading to the rediscovery of forgotten literatures and the worlds they were associated with—for example, Beowulf, the Poetic Edda, the Nibelungenlied, and the oral traditions compiled in the Kalevala. These discoveries had a huge impact, not only literary, but political, as the recovery of national literatures helped to support emergent nationalism, in Germany, Finland, and elsewhere. This led, in turn, to the self-conscious revival of ancient forms, most notably in William Morris' romantic fantasies and Wagner's use of stabreim, or alliterative verse, in the libretto for his opera series, the Ring of the Nibelungs. Wagner's Ring electrified a generation—including budding scholars like C. S. Lewis. The romantic view of the ancient North, expressed not only by Wagner but by Morris and other English romantics, led to an increasing interest in alliterative verse.

Alliterative Verse in Modernist Poetics

The rediscovery of alliterative verse played a role in the modernist rebellion against traditional poetic forms, most notably in Ezra Pound's Cantos (e.g., Canto I). Multiple modernist poets experimented with alliterative verse, including W.H. Auden in The Age of Anxiety, Richard Eberhart in Brotherhood of Men, and later, Richard Wilbur and Ted Hughes. However, these experiments are experiments more with the idea of alliterative verse than with traditional alliterative meters. For instance, many of the following lines from The Age of Anxiety violate basic principles of alliterative meter, such as placing stress and alliteration on grammatical function words like "yes" and "you":

Deep in my dark. the dream shines

Yes, of you you dear always;

My cause to cry, cold but my

Story still, still my music.

Mild rose the moon, moving through our

Naked nights: tonight it rains;

Black umbrellas: blossom out;

Gone the gold, my golden ball.

…

Richard Wilbur's Junk comes closer to matching alliterative rhythms, but freely alliterates on the fourth stress, sometimes alliterating all four stresses in the same line (which an Old English poet would not, and a Middle English poet only rarely do), as in the poem's opening lines:

An axe angles from my neighbor's ashcan;

It is hell's handiwork, the wood not hickory.

The flow of the grain not faithfully followed.

The shivered shaft rises from a shellheap

Of plastic playthings, paper plates.

...

In his 1978 article on the potential of alliterative meter as a form in modern English, John D. Niles characterizes these experiments as essentially one-offs, rather than as part of an ongoing tradition.

The Inklings as Alliterative Poets

A rather different approach to reviving alliterative verse appears in the work of the so-called Inklings, specifically, J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. Both were medievalist scholars, and as such, were familiar with alliterative metrics. Both of them made serious attempts to use and advocate the use of traditional alliterative forms in modern English (though many of Tolkien's alliterative poems were not published until long after his death).

J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973) was a scholar of Old and Middle English as well as a fantasy author and used alliterative verse extensively in both translations and original poetry; some of his poems are embedded in the text of his fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings. Most of his alliterative verse is in modern English, in a variety of styles. Tolkien's longest modern English works in Old English alliterative meter are an alliterative verse play, The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son describing the aftermath of the Battle of Maldon, published in 1953, his 2276-line The Lay of the Children of Húrin (c. 1918–1925), published in 1985, and his thousand-line fragment on the Matter of Britain, The Fall of Arthur, published in 2013. He also experimented with alliterative verse based on the Poetic Edda (e.g., the Völsungasaga and Atlakviða) in The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun (2009). His Gothic poem Bagme Bloma ("Flower of the Trees") uses a trochaic metre, with irregular end-rhymes and irregular alliteration in each line; it was published in the 1936 Songs for the Philologists.[144] He also wrote a variety of alliterative poems in Old English. A version of these appears in "The Notion Club Papers". His alliterative verse translations of Old English and Middle English alliterative poems include some 600 lines of Beowulf, portions of The Seafarer, and a complete translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Tolkien's original alliterative verse follows the rules for Old English alliterative verse, as can be seen in the following lines from The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son:

To the left yonder

There's a shade creeping, a shadow darker

than the western sky, there walking crouched!

Two now together! Troll-shapes, I guess

or hell-walkers. They've a halting gait,

groping groundwards with grisly arms.

C. S. Lewis

Like Tolkien, C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) taught at Oxford University, where he was Fellow and Tutor in English Literature at Magdalen College. He was later a full Professor at Cambridge University. He is best known for his work as a literary critic and Christian apologist, but he also wrote a variety of modern English poems in Old English alliterative meter. His alliterative poetry includes "Sweet Desire" and "The Planets" in his collected Poems and the 742-line poem "The Nameless Isle" in his Narrative Poems. He also wrote an article on the use of alliterative meter in modern English. Like Tolkien, his poems follow the rules of Old English alliterative verse, while maintaining modern English diction and syntax, as can be seen from lines 562-67 of The Nameless Isle:

The marble maid, under mask of stone

shook and shuddered. As a shadow streams

Over the wheat waving, over the woman's face

Life came lingering. Nor was it long after

Down its blue pathways, blood returning

Moved, and mounted to her maiden cheek.

Alliterative Translations of Alliterative Verse

The late twentieth and early 21st century saw multiple serious efforts by renowned poets to render prominent Old and Middle English poems in modern English alliterative verse. These include Allan Sullivan and Timothy Murphy's translations of Beowulf, Simon Armitage's translations of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Pearl, and Tony Harrison's translation of the York Mystery Plays. In combination with the posthumous publication of J.R.R. Tolkien's alliterative poems, this has resulted in modern alliterative renderings of alliterative verse becoming much more accessible to the general public.

The Speculative Alliterative Revival

During the latter part of the 20th and early 21st Century, alliterative verse enjoyed a revival in speculative fiction and associated social spaces, including historical reenactment, fan fiction, and related social movements. This revival was associated with the American fantasy and science fiction author Poul Anderson, who embedded alliterative verse in many of his science fiction and fantasy novels, and with younger authors like Paul Edwin Zimmer who belonged to the same social circles. Their work largely circulated in fanzines and small speculative poetry journals like Star*Line, though after the foundation of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA) in the 1960s, it found a new home in occasional verse written for SCA events, where fantasy and science fiction authors and fans were likely to rub shoulders with medievalist scholars and neopagan devotees of the old Germanic gods. Alliterative verse can be found wherever speculative fiction fans gather, including fanfiction sites and even in materials written for roleplaying games (RPGs).