| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tantalum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈtæntələm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | gray blue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Ta) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tantalum in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 73 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d3 6s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 11, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 3290 K (3017 °C, 5463 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 5731 K (5458 °C, 9856 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 16.678 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 15 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 36.57 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 753 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.36 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +5 −3, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 146 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 170±8 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc) (cI2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 330.29 pm (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 6.3 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 57.5 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 131 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +154.0×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 186 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 69 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 200 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 3400 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 6.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 870–1200 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 440–3430 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-25-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Anders Gustaf Ekeberg (1802) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized as a distinct element by | Heinrich Rose (1844) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

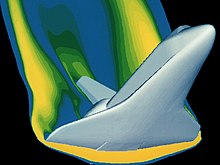

Tantalum is a chemical element; it has symbol Ta and atomic number 73. It is named after Tantalus, a figure in Greek mythology. Tantalum is a very hard, ductile, lustrous, blue-gray transition metal that is highly corrosion-resistant. It is part of the refractory metals group, which are widely used as components of strong high-melting-point alloys. It is a group 5 element, along with vanadium and niobium, and it always occurs in geologic sources together with the chemically similar niobium, mainly in the mineral groups tantalite, columbite and coltan.

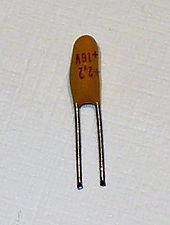

The chemical inertness and very high melting point of tantalum make it valuable for laboratory and industrial equipment such as reaction vessels and vacuum furnaces. It is used in tantalum capacitors for electronic equipment such as computers. It is being investigated for use as a material for high-quality superconducting resonators in quantum processors.

History

Tantalum was discovered in Sweden in 1802 by Anders Ekeberg, in two mineral samples – one from Sweden and the other from Finland. One year earlier, Charles Hatchett had discovered columbium (now niobium). In 1809, the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston compared the oxides of columbium and tantalum, columbite and tantalite. Although the two oxides had different measured densities of 5.918 g/cm3 and 7.935 g/cm3, he concluded that they were identical and kept the name tantalum. After Friedrich Wöhler confirmed these results, it was thought that columbium and tantalum were the same element. This conclusion was disputed in 1846 by the German chemist Heinrich Rose, who argued that there were two additional elements in the tantalite sample, and he named them after the children of Tantalus: niobium (from Niobe), and pelopium (from Pelops). The supposed element "pelopium" was later identified as a mixture of tantalum and niobium, and it was found that the niobium was identical to the columbium already discovered in 1801 by Hatchett.

The differences between tantalum and niobium were demonstrated unequivocally in 1864 by Christian Wilhelm Blomstrand, and Henri Etienne Sainte-Claire Deville, as well as by Louis J. Troost, who determined the empirical formulas of some of their compounds in 1865. Further confirmation came from the Swiss chemist Jean Charles Galissard de Marignac, in 1866, who proved that there were only two elements. These discoveries did not stop scientists from publishing articles about the so-called ilmenium until 1871. De Marignac was the first to produce the metallic form of tantalum in 1864, when he reduced tantalum chloride by heating it in an atmosphere of hydrogen. Early investigators had only been able to produce impure tantalum, and the first relatively pure ductile metal was produced by Werner von Bolton in Charlottenburg in 1903. Wires made with metallic tantalum were used for light bulb filaments until tungsten replaced it in widespread use.

The name tantalum was derived from the name of the mythological Tantalus, the father of Niobe in Greek mythology. In the story, he had been punished after death by being condemned to stand knee-deep in water with perfect fruit growing above his head, both of which eternally tantalized him. (If he bent to drink the water, it drained below the level he could reach, and if he reached for the fruit, the branches moved out of his grasp.) Anders Ekeberg wrote "This metal I call tantalum ... partly in allusion to its incapacity, when immersed in acid, to absorb any and be saturated."

For decades, the commercial technology for separating tantalum from niobium involved the fractional crystallization of potassium heptafluorotantalate away from potassium oxypentafluoroniobate monohydrate, a process that was discovered by Jean Charles Galissard de Marignac in 1866. This method has been supplanted by solvent extraction from fluoride-containing solutions of tantalum.

Characteristics

Physical properties

Tantalum is dark (blue-gray), dense, ductile, very hard, easily fabricated, and highly conductive of heat and electricity. The metal is highly resistant to corrosion by acids: at temperatures below 150 °C tantalum is almost completely immune to attack by the normally aggressive aqua regia. It can be dissolved with hydrofluoric acid or acidic solutions containing the fluoride ion and sulfur trioxide, as well as with molten potassium hydroxide. Tantalum's high melting point of 3017 °C (boiling point 5458 °C) is exceeded among the elements only by tungsten, rhenium and osmium for metals, and carbon.

Tantalum exists in two crystalline phases, alpha and beta. The alpha phase is stable at all temperatures up to the melting point and has body-centered cubic structure with lattice constant a = 0.33029 nm at 20 °C. It is relatively ductile, has Knoop hardness 200–400 HN and electrical resistivity 15–60 μΩ⋅cm. The beta phase is hard and brittle; its crystal symmetry is tetragonal (space group P42/mnm, a = 1.0194 nm, c = 0.5313 nm), Knoop hardness is 1000–1300 HN and electrical resistivity is relatively high at 170–210 μΩ⋅cm. The beta phase is metastable and converts to the alpha phase upon heating to 750–775 °C. Bulk tantalum is almost entirely alpha phase, and the beta phase usually exists as thin films obtained by magnetron sputtering, chemical vapor deposition or electrochemical deposition from a eutectic molten salt solution.

Isotopes

Natural tantalum consists of two stable isotopes: 180mTa (0.012%) and 181Ta (99.988%). 180mTa (m denotes a metastable state) is predicted to decay in three ways: isomeric transition to the ground state of 180Ta, beta decay to 180W, or electron capture to 180Hf. However, radioactivity of this nuclear isomer has never been observed, and only a lower limit on its half-life of 2.9×1017 years has been set. The ground state of 180Ta has a half-life of only 8 hours. 180mTa is the only naturally occurring nuclear isomer (excluding radiogenic and cosmogenic short-lived nuclides). It is also the rarest primordial isotope in the Universe, taking into account the elemental abundance of tantalum and isotopic abundance of 180mTa in the natural mixture of isotopes (and again excluding radiogenic and cosmogenic short-lived nuclides).

Tantalum has been examined theoretically as a "salting" material for nuclear weapons (cobalt is the better-known hypothetical salting material). An external shell of 181Ta would be irradiated by the intensive high-energy neutron flux from a hypothetical exploding nuclear weapon. This would transmute the tantalum into the radioactive isotope 182Ta, which has a half-life of 114.4 days and produces gamma rays with approximately 1.12 million electron-volts (MeV) of energy apiece, which would significantly increase the radioactivity of the nuclear fallout from the explosion for several months. Such "salted" weapons have never been built or tested, as far as is publicly known, and certainly never used as weapons.

Tantalum can be used as a target material for accelerated proton beams for the production of various short-lived isotopes including 8Li, 80Rb, and 160Yb.

Chemical compounds

Tantalum forms compounds in oxidation states −III to +V. Most commonly encountered are oxides of Ta(V), which includes all minerals. The chemical properties of Ta and Nb are very similar. In aqueous media, Ta only exhibit the +V oxidation state. Like niobium, tantalum is barely soluble in dilute solutions of hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric and phosphoric acids due to the precipitation of hydrous Ta(V) oxide. In basic media, Ta can be solubilized due to the formation of polyoxotantalate species.

Oxides, nitrides, carbides, sulfides

Tantalum pentoxide (Ta2O5) is the most important compound from the perspective of applications. Oxides of tantalum in lower oxidation states are numerous, including many defect structures, and are lightly studied or poorly characterized.

Tantalates, compounds containing [TaO4]3− or [TaO3]− are numerous. Lithium tantalate (LiTaO3) adopts a perovskite structure. Lanthanum tantalate (LaTaO4) contains isolated TaO3−

4 tetrahedra.

As in the cases of other refractory metals, the hardest known compounds of tantalum are nitrides and carbides. Tantalum carbide, TaC, like the more commonly used tungsten carbide, is a hard ceramic that is used in cutting tools. Tantalum(III) nitride is used as a thin film insulator in some microelectronic fabrication processes.

The best studied chalcogenide is Tantalum sulfide (TaS2), a layered semiconductor, as seen for other transition metal dichalcogenides. A tantalum-tellurium alloy forms quasicrystals.

Halides

Tantalum halides span the oxidation states of +5, +4, and +3. Tantalum pentafluoride (TaF5) is a white solid with a melting point of 97.0 °C. The anion [TaF7]2- is used for its separation from niobium. The chloride TaCl

5, which exists as a dimer, is the main reagent in synthesis of new Ta compounds. It hydrolyzes readily to an oxychloride. The lower halides TaX

4 and TaX

3, feature Ta-Ta bonds.

Organotantalum compounds

Organotantalum compounds include pentamethyltantalum, mixed alkyltantalum chlorides, alkyltantalum hydrides, alkylidene complexes as well as cyclopentadienyl derivatives of the same. Diverse salts and substituted derivatives are known for the hexacarbonyl [Ta(CO)6]− and related isocyanides.

Occurrence

Tantalum is estimated to make up about 1 ppm or 2 ppm of the Earth's crust by weight. There are many species of tantalum minerals, only some of which are so far being used by industry as raw materials: tantalite (a series consisting of tantalite-(Fe), tantalite-(Mn) and tantalite-(Mg)), microlite (now a group name), wodginite, euxenite (actually euxenite-(Y)), and polycrase (actually polycrase-(Y)). Tantalite (Fe, Mn)Ta2O6 is the most important mineral for tantalum extraction. Tantalite has the same mineral structure as columbite (Fe, Mn) (Ta, Nb)2O6; when there is more tantalum than niobium it is called tantalite and when there is more niobium than tantalum is it called columbite (or niobite). The high density of tantalite and other tantalum containing minerals makes the use of gravitational separation the best method. Other minerals include samarskite and fergusonite.

Australia was the main producer of tantalum prior to the 2010s, with Global Advanced Metals (formerly known as Talison Minerals) being the largest tantalum mining company in that country. They operate two mines in Western Australia, Greenbushes in the southwest and Wodgina in the Pilbara region. The Wodgina mine was reopened in January 2011 after mining at the site was suspended in late 2008 due to the global financial crisis. Less than a year after it reopened, Global Advanced Metals announced that due to again "... softening tantalum demand ...", and other factors, tantalum mining operations were to cease at the end of February 2012. Wodgina produces a primary tantalum concentrate which is further upgraded at the Greenbushes operation before being sold to customers. Whereas the large-scale producers of niobium are in Brazil and Canada, the ore there also yields a small percentage of tantalum. Some other countries such as China, Ethiopia, and Mozambique mine ores with a higher percentage of tantalum, and they produce a significant percentage of the world's output of it. Tantalum is also produced in Thailand and Malaysia as a by-product of the tin mining there. During gravitational separation of the ores from placer deposits, not only is cassiterite (SnO2) found, but a small percentage of tantalite also included. The slag from the tin smelters then contains economically useful amounts of tantalum, which is leached from the slag.

World tantalum mine production has undergone an important geographic shift since the start of the 21st century when production was predominantly from Australia and Brazil. Beginning in 2007 and through 2014, the major sources of tantalum production from mines dramatically shifted to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, and some other African countries. Future sources of supply of tantalum, in order of estimated size, are being explored in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Greenland, China, Mozambique, Canada, Australia, the United States, Finland, and Brazil.

Status as a conflict resource

Tantalum is considered a conflict resource. Coltan, the industrial name for a columbite–tantalite mineral from which niobium and tantalum are extracted, can also be found in Central Africa, which is why tantalum is being linked to warfare in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). According to an October 23, 2003 United Nations report, the smuggling and exportation of coltan has helped fuel the war in the Congo, a crisis that has resulted in approximately 5.4 million deaths since 1998 – making it the world's deadliest documented conflict since World War II. Ethical questions have been raised about responsible corporate behavior, human rights, and endangering wildlife, due to the exploitation of resources such as coltan in the armed conflict regions of the Congo Basin. The United States Geological Survey reports in its yearbook that this region produced a little less than 1% of the world's tantalum output in 2002–2006, peaking at 10% in 2000 and 2008. USGS data published in January 2021 indicated that close to 40% of the world's tantalum mine production came from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with another 18% coming from neighboring Rwanda and Burundi.

Production and fabrication

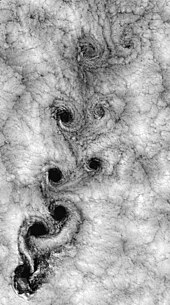

Several steps are involved in the extraction of tantalum from tantalite. First, the mineral is crushed and concentrated by gravity separation. This is generally carried out near the mine site.

Refining

The refining of tantalum from its ores is one of the more demanding separation processes in industrial metallurgy. The chief problem is that tantalum ores contain significant amounts of niobium, which has chemical properties almost identical to those of Ta. A large number of procedures have been developed to address this challenge.

In modern times, the separation is achieved by hydrometallurgy. Extraction begins with leaching the ore with hydrofluoric acid together with sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid. This step allows the tantalum and niobium to be separated from the various non-metallic impurities in the rock. Although Ta occurs as various minerals, it is conveniently represented as the pentoxide, since most oxides of tantalum(V) behave similarly under these conditions. A simplified equation for its extraction is thus:

- Ta2O5 + 14 HF → 2 H2[TaF7] + 5 H2O

Completely analogous reactions occur for the niobium component, but the hexafluoride is typically predominant under the conditions of the extraction.

- Nb2O5 + 12 HF → 2 H[NbF6] + 5 H2O

These equations are simplified: it is suspected that bisulfate (HSO4−) and chloride compete as ligands for the Nb(V) and Ta(V) ions, when sulfuric and hydrochloric acids are used, respectively. The tantalum and niobium fluoride complexes are then removed from the aqueous solution by liquid-liquid extraction into organic solvents, such as cyclohexanone, octanol, and methyl isobutyl ketone. This simple procedure allows the removal of most metal-containing impurities (e.g. iron, manganese, titanium, zirconium), which remain in the aqueous phase in the form of their fluorides and other complexes.

Separation of the tantalum from niobium is then achieved by lowering the ionic strength of the acid mixture, which causes the niobium to dissolve in the aqueous phase. It is proposed that oxyfluoride H2[NbOF5] is formed under these conditions. Subsequent to removal of the niobium, the solution of purified H2[TaF7] is neutralised with aqueous ammonia to precipitate hydrated tantalum oxide as a solid, which can be calcined to tantalum pentoxide (Ta2O5).

Instead of hydrolysis, the H2[TaF7] can be treated with potassium fluoride to produce potassium heptafluorotantalate:

- H2[TaF7] + 2 KF → K2[TaF7] + 2 HF

Unlike H2[TaF7], the potassium salt is readily crystallized and handled as a solid.

K2[TaF7] can be converted to metallic tantalum by reduction with sodium, at approximately 800 °C in molten salt.

- K2[TaF7] + 5 Na → Ta + 5 NaF + 2 KF

In an older method, called the Marignac process, the mixture of H2[TaF7] and H2[NbOF5] was converted to a mixture of K2[TaF7] and K2[NbOF5], which was then separated by fractional crystallization, exploiting their different water solubilities.

Electrolysis

Tantalum can also be refined by electrolysis, using a modified version of the Hall–Héroult process. Instead of requiring the input oxide and output metal to be in liquid form, tantalum electrolysis operates on non-liquid powdered oxides. The initial discovery came in 1997 when Cambridge University researchers immersed small samples of certain oxides in baths of molten salt and reduced the oxide with electric current. The cathode uses powdered metal oxide. The anode is made of carbon. The molten salt at 1,000 °C (1,830 °F) is the electrolyte. The first refinery has enough capacity to supply 3–4% of annual global demand.

Fabrication and metalworking

All welding of tantalum must be done in an inert atmosphere of argon or helium in order to shield it from contamination with atmospheric gases. Tantalum is not solderable. Grinding tantalum is difficult, especially so for annealed tantalum. In the annealed condition, tantalum is extremely ductile and can be readily formed as metal sheets.

Applications

Electronics

The major use for tantalum, as the metal powder, is in the production of electronic components, mainly capacitors and some high-power resistors. Tantalum electrolytic capacitors exploit the tendency of tantalum to form a protective oxide surface layer, using tantalum powder, pressed into a pellet shape, as one "plate" of the capacitor, the oxide as the dielectric, and an electrolytic solution or conductive solid as the other "plate". Because the dielectric layer can be very thin (thinner than the similar layer in, for instance, an aluminium electrolytic capacitor), a high capacitance can be achieved in a small volume. Because of the size and weight advantages, tantalum capacitors are attractive for portable telephones, personal computers, automotive electronics and cameras.

Alloys

Tantalum is also used to produce a variety of alloys that have high melting points, strength, and ductility. Alloyed with other metals, it is also used in making carbide tools for metalworking equipment and in the production of superalloys for jet engine components, chemical process equipment, nuclear reactors, missile parts, heat exchangers, tanks, and vessels. Because of its ductility, tantalum can be drawn into fine wires or filaments, which are used for evaporating metals such as aluminium.

Tantalum is inert against most acids except hydrofluoric acid and hot sulfuric acid, and hot alkaline solutions also cause tantalum to corrode. This property makes it a useful metal for chemical reaction vessels and pipes for corrosive liquids. Heat exchanging coils for the steam heating of hydrochloric acid are made from tantalum. Tantalum was extensively used in the production of ultra high frequency electron tubes for radio transmitters. Tantalum is capable of capturing oxygen and nitrogen by forming nitrides and oxides and therefore helped to sustain the high vacuum needed for the tubes when used for internal parts such as grids and plates.

Surgical uses

Medical researcher Gerald L. Burke at the Los Angeles Orthopaedic Hospital first discovered in 1938 that tantalum is bio-inert in human tissue and could be used safely as an orthopaedic implant material. Burke also demonstrated perhaps the other most appreciated characteristic of tantalum in surgical procedures: tantalum would permanently bond to bone with no degradation of the surrounding bone. Later, Burke's team working with a team from the California Institute of Technology led by John Norton Wilson showed that tantalum, while hard enough to be fabricated into surgical tools, could also be fabricated in a form sufficiently ductile, yet still sufficiently strong to be drawn into fine threads that could be used for non-scarring sutures. Burke's team in 1940 was the first to propose the use of tantalum for arthroplasty procedures, the repair of intertrochanteric fractures, and for jaw repairs and dental implants. Burke's initial biological research results were confirmed and credited in greater detail by the Harvard Medical School in a series of neurological experiments using powdered tantalum implants. More than 50 years later, researchers were still refining and documenting their understanding of the basic surgical procedures developed by Burke after his pioneering discoveries.

Nowadays, in spite of the cost, tantalum is still widely used in making surgical instruments and implants, and new procedures continue to be developed. For example, porous tantalum coatings are used in the construction of titanium implants due to tantalum's exceptional ability to form a direct bond to hard tissue. Because tantalum is a non-ferrous, non-magnetic metal, tantalum implants are considered to be acceptable for patients undergoing MRI procedures.

Other uses

Tantalum was used by NASA to shield components of spacecraft, such as Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, from radiation. The high melting point and oxidation resistance led to the use of the metal in the production of vacuum furnace parts. Tantalum is extremely inert and is therefore formed into a variety of corrosion resistant parts, such as thermowells, valve bodies, and tantalum fasteners. Due to its high density, shaped charge and explosively formed penetrator liners have been constructed from tantalum. Tantalum greatly increases the armor penetration capabilities of a shaped charge due to its high density and high melting point. It is also occasionally used in precious watches e.g. from Audemars Piguet, F.P. Journe, Hublot, Montblanc, Omega, and Panerai. Tantalum oxide is used to make special high refractive index glass for camera lenses. Spherical tantalum powder, produced by atomizing molten tantalum using gas or liquid, is commonly used in additive manufacturing due to its uniform shape, excellent flowability, and high melting point.

Environmental issues

Tantalum receives far less attention in the environmental field than it does in other geosciences. Upper Crust Concentration (UCC) and the Nb/Ta ratio in the upper crust and in minerals are available because these measurements are useful as a geochemical tool. The latest value for upper crust concentration is 0.92 ppm, and the Nb/Ta(w/w) ratio stands at 12.7.

Little data is available on tantalum concentrations in the different environmental compartments, especially in natural waters where reliable estimates of ‘dissolved’ tantalum concentrations in seawater and freshwaters have not even been produced. Some values on dissolved concentrations in oceans have been published, but they are contradictory. Values in freshwaters fare little better, but, in all cases, they are probably below 1 ng L−1, since ‘dissolved’ concentrations in natural waters are well below most current analytical capabilities. Analysis requires pre-concentration procedures that, for the moment, do not give consistent results. And in any case, tantalum appears to be present in natural waters mostly as particulate matter rather than dissolved.

Values for concentrations in soils, bed sediments and atmospheric aerosols are easier to come by. Values in soils are close to 1 ppm and thus to UCC values. This indicates detrital origin. For atmospheric aerosols the values available are scattered and limited. When tantalum enrichment is observed, it is probably due to loss of more water-soluble elements in aerosols in the clouds.

Pollution linked to human use of the element has not been detected. Tantalum appears to be a very conservative element in biogeochemical terms, but its cycling and reactivity are still not fully understood.

Precautions

Compounds containing tantalum are rarely encountered in the laboratory. The metal is highly biocompatible and is used for body implants and coatings, therefore attention may be focused on other elements or the physical nature of the chemical compound.

People can be exposed to tantalum in the workplace by breathing it in, skin contact, or eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for tantalum exposure in the workplace as 5 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 5 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday and a short-term limit of 10 mg/m3. At levels of 2500 mg/m3, tantalum dust is immediately dangerous to life and health.