Space policy process

United States space policy is drafted by the Executive branch at the direction of the President of the United States, and submitted for approval and establishment of funding to the legislative process of the United States Congress.

Space advocacy organizations may provide advice to the government and lobby for space goals. These include advocacy groups such as the Space Science Institute, National Space Society, and the Space Generation Advisory Council, the last of which among other things runs the annual Yuri's Night event; learned societies such as the American Astronomical Society and the American Astronautical Society; and policy organizations such as the National Academies.

Drafting

In drafting space policy, the President consults with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), responsible for civilian and scientific space programs, and with the Department of Defense,

responsible for military space activities, which include

communications, reconnaissance, intelligence, mapping, and missile

defense. The President is legally responsible for deciding which space activities fall under the civilian and military areas. The President also consults with the National Security Council, the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the Office of Management and Budget.

The 1958 National Aeronautics and Space Act, which created NASA, created a National Aeronautics and Space Council chaired by the President to help advise him, which included the Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, NASA Administrator, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission,

plus up to one member of the federal government, and up to three

private individuals "eminent in science, engineering, technology,

education, administration, or public affairs" appointed by the

President. Before taking office as President, John F. Kennedy

persuaded Congress to amend the Act to allow him to set the precedent

of delegating chairmanship of this council to his Vice President (Lyndon B. Johnson). The Council was discontinued in 1973 during the presidency of Richard M. Nixon. In 1989, President George H. W. Bush re-established a differently constituted National Space Council by executive order, which was discontinued in 1993 by President Bill Clinton. President Donald Trump reestablished the Council by executive order in 2017.

International aspects of US space policy may involve diplomatic negotiation with other countries, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. In these cases, the President negotiates and signs the treaty on behalf of the United States according to his constitutional authority, then presents it to the Congress for ratification.

Legislation

Once

a request is submitted, the Congress exercises due diligence to approve

the policy and authorize a budgetary expenditure for its

implementation. In support of this, civilian policies are reviewed by

the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics and the Senate Subcommittee on Science and Space.

These committees may exercise oversight of NASA's implementation of

established space policies, monitoring progress of large space programs

such as the Apollo program, and in special cases such as serious space accidents like the Apollo 1 fire, where Congress oversees NASA's investigation of the accident.

Military policies are reviewed and overseen by the House Subcommittee on Strategic Forces and the Senate Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, as well as the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee

conducts hearings on proposed space treaties, and the various

appropriations committees have power over the budgets for space-related

agencies. Space policy efforts are supported by Congressional agencies

such as the Congressional Research Service and, until it was disbanded in 1995, the Office of Technology Assessment, as well as the Congressional Budget Office and Government Accountability Office.

Congress' final space policy product is, in the case of domestic

policy a bill explicitly stating the policy objectives and the budget

appropriation for their implementation to be submitted to the President

for signature into law, or else a ratified treaty with other nations.

Implementation

Civilian

space activities have traditionally been implemented exclusively by

NASA, but the nation is transitioning into a model where more activities

are implemented by private companies under NASA's advisement and launch

site support. In addition, the Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration operates various services with space components, such as the Landsat program.

Military space activities are implemented by the Air Force Space Command, Naval Space Command, and Army Space and Missile Defense Command.

Licensing

Any

activities "which are intended to conduct in the United States a launch

of a launch vehicle, operation of a launch or re-entry site, re-entry

of a re-entry vehicle" needs a license to operate in outer space. This

license needs to by applied for by "any citizen of or entity organized

under the laws of the United States, as well as other entities, as

defined by space-related regulations, which are intended to conduct in

the United States… should obtain a license form the Secretary of Transportation" compliance is monitored by the FAA, FCC and the Secretary of Commerce.

Space programs in the budget

Funding for space programs occurs through the federal budget process, where it is mainly considered to be part of the nation's science policy. In the Obama administration's budget request for fiscal year 2011, NASA would receive $11.0 billion, out of a total research and development budget of $148.1 billion. Other space activities are funded out of the research and development budget of the Department of Defense, and from the budgets of the other regulatory agencies involved with space issues.

International law

The United States is a party to four of the five space law treaties ratified by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The United States has ratified the Outer Space Treaty, Rescue Agreement, Space Liability Convention, and the Registration Convention, but not the Moon Treaty.

The five treaties and agreements of international space law cover

"non-appropriation of outer space by any one country, arms control, the

freedom of exploration, liability for damage caused by space objects,

the safety and rescue of spacecraft and astronauts, the prevention of

harmful interference with space activities and the environment, the

notification and registration of space activities, scientific

investigation and the exploitation of natural resources in outer space

and the settlement of disputes."

The United Nations General Assembly

adopted five declarations and legal principles which encourage

exercising the international laws, as well as unified communication

between countries. The five declarations and principles are:

- The Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Uses of Outer Space (1963)

- All space exploration will be done with good intentions and is equally open to all States that comply with international law. No one nation may claim ownership of outer space or any celestial body. Activities carried out in space must abide by the international law and the nations undergoing these said activities must accept responsibility for the governmental or non-governmental agency involved. Objects launched into space are subject to their nation of belonging, including people. Objects, parts, and components discovered outside the jurisdiction of a nation will be returned upon identification. If a nation launches an object into space, they are responsible for any damages that occur internationally.

- The Principles Governing the Use by States of Artificial Earth Satellites for International Direct Television Broadcasting (1982)

- The Principles Relating to Remote Sensing of the Earth from Outer Space (1986)

- The Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space (1992)

- The Declaration on International Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for the Benefit and in the Interest of All States, Taking into Particular Account the Needs of Developing Countries (1996)

History

Eisenhower administration

President Dwight Eisenhower was skeptical about human spaceflight, but sought to advance the commercial and military applications of satellite technology. Prior to the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik 1, Eisenhower had already authorized Project Vanguard, a scientific satellite program associated with the International Geophysical Year. As a supporter of small government, he sought to avoid a space race which would require an expensive bureaucracy to conduct, and was surprised by, and sought to downplay, the public response to the Soviet launch of Sputnik. In an effort to prevent similar technological surprises by the Soviets, Eisenhower authorized the creation in 1958 of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), responsible for the development of advanced military technologies.

Space programs such as the Explorer satellite were proposed by the Army Ballistic Missile Agency

(ABMA), but Eisenhower, seeking to avoid giving the US space program

the militaristic image Americans had of the Soviet program, had rejected

Explorer in favor of the Vanguard, but after numerous embarrassing

Vanguard failures, was forced to give the go-ahead to the Army's launch.

Later in 1958, Eisenhower asked Congress to create an agency for

civilian control of non-military space activities. At the suggestion of

Eisenhower's science advisor James R. Killian, the drafted bill called for creation of the new agency out of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. The result was the National Aeronautics and Space Act passed in July 1958, which created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Eisenhower appointed T. Keith Glennan as NASA's first Administrator, with the last NACA Director Hugh Dryden serving as his Deputy.

NASA as created in the act passed by Congress was substantially

stronger than the Eisenhower administration's original proposal. NASA

took over the space technology research started by DARPA. NASA also took over the US manned satellite program, Man In Space Soonest, from the Air Force, as Project Mercury.

Kennedy administration

Early in John F. Kennedy's presidency, he was inclined to dismantle plans for the Apollo program,

which he had opposed as a senator, but postponed any decision out of

deference to his vice president whom he had appointed chairman of the National Advisory Space Council and who strongly supported NASA due to its Texas location. This changed with his January 1961 State of the Union address, when he suggested international cooperation in space.

In response to the flight of Yuri Gagarin as the first man in space, Kennedy in 1961 committed the United States to landing a man on the Moon

by the end of the decade. At the time, the administration believed

that the Soviet Union would be able to land a man on the Moon by 1967,

and Kennedy saw an American Moon landing as critical to the nation's

global prestige and status. His pick for NASA administrator, James E. Webb,

however pursued a broader program incorporating space applications such

as weather and communications satellites. During this time the

Department of Defense pursued military space applications such as the Dyna-Soar spaceplane program and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory. Kennedy also had elevated the status of the National Advisory Space Council by assigning the Vice President as its chair.

Johnson administration

President Lyndon Johnson was committed to space efforts, and as Senate majority leader

and Vice President, he had contributed much to setting up the

organizational infrastructure for the space program. However, the costs

of the Vietnam War and the programs of the Great Society forced cuts to NASA's budget as early as 1965. However, the Apollo 8 mission carrying the first men into lunar orbit occurred just before the end of his term in 1968.

Nixon administration

President Nixon visits the Apollo 11 astronauts in quarantine after observing their landing in the ocean from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.

Apollo 11, the first Moon landing, occurred early in Richard Nixon's presidency, but NASA's budget continued to decline and three of the planned Apollo Moon landings were cancelled. The Nixon administration approved the beginning of the Space Shuttle program, but did not support funding of other projects such as a Mars landing, colonization of the Moon, or a permanent space station.

On January 5, 1972, Nixon approved the development of NASA's Space Shuttle program,

a decision that profoundly influenced American efforts to explore and

develop space for several decades thereafter. Under the Nixon

administration, however, NASA's budget declined. NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine was drawing up ambitious plans for the establishment of a permanent base on the Moon by the end of the 1970s and the launch of a manned expedition to Mars as early as 1981. Nixon, however, rejected this proposal. On May 24, 1972, Nixon approved a five-year cooperative program between NASA and the Soviet space program, which would culminate in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, a joint-mission of an American Apollo and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft, during Gerald Ford's presidency in 1975.

Ford administration

Space policy had little momentum during the presidency of Gerald Ford. NASA funding improved somewhat, the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project occurred and the Shuttle program continued, and the Office of Science and Technology Policy was formed.

Carter administration

The Jimmy Carter administration

was also fairly inactive on space issues, stating that it was "neither

feasible nor necessary" to commit to an Apollo-style space program, and

his space policy included only limited, short-range goals.

With regard to military space policy, the Carter space policy stated,

without much specification in the unclassified version, that "The United

States will pursue Activities in space in support of its right of

self-defense."

Reagan administration

President Reagan delivering the March 23, 1983 speech initiating the Strategic Defense Initiative.

The first flight of the Space Shuttle occurred in April 1981, early in President Ronald Reagan's first term. Reagan in 1982 announced a renewed active space effort, which included initiatives such as privatization of the Landsat program, a new commercialization policy for NASA, the construction of Space Station Freedom, and the military Strategic Defense Initiative. Late in his term as president, Reagan sought to increase NASA's budget by 30 percent. However, many of these initiatives would not be completed as planned.

The January 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster led to the Rogers Commission Report on the causes of the disaster, and the National Commission on Space report and Ride Report on the future of the national space program.

George H. W. Bush administration

President George H. W. Bush continued to support space development, announcing the bold Space Exploration Initiative, and ordering a 20 percent increase in NASA's budget in a tight budget era. The Bush administration also commissioned another report on the future of NASA, the Advisory Committee on the Future of the United States Space Program, also known as the Augustine Report.

Clinton administration

During the Clinton administration, Space Shuttle flights continued, and the construction of the International Space Station began.

The Clinton administration's National Space Policy (Presidential

Decision Directive/NSC-49/NSTC-8) was released on September 14, 1996.

Clinton's top goals were to "enhance knowledge of the Earth, the solar

system and the universe through human and robotic exploration" and to

"strengthen and maintain the national security of the United States."

The Clinton space policy, like the space policies of Carter and

Reagan, also stated that "The United States will conduct those space

activities necessary for national security." These activities included

"providing support for the United States' inherent right of self-defense

and our defense commitments to allies and friends; deterring, warning,

and if necessary, defending against enemy attack; assuring that hostile

forces cannot prevent our own use of space; and countering, if

necessary, space systems and services used for hostile purposes."

The Clinton policy also said the United States would develop and

operate "space control capabilities to ensure freedom of action in

space" only when such steps would be "consistent with treaty

obligations."

George W. Bush administration

The launch of the Ares I-X prototype on October 28, 2009 was the only flight performed under the Bush administration's Constellation program.

The Space Shuttle Columbia disaster occurred early in George W. Bush's term, leading to the report of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board being released in August 2003. The Vision for Space Exploration, announced on January 14, 2004 by President George W. Bush, was seen as a response to the Columbia disaster and the general state of human spaceflight at NASA, as well as a way to regain public enthusiasm for space exploration.

The Vision for Space Exploration sought to implement a sustained and

affordable human and robotic program to explore the solar system and

beyond; extend human presence across the solar system, starting with a

human return to the Moon by the year 2020, in preparation for human

exploration of Mars and other destinations; develop the innovative

technologies, knowledge, and infrastructures both to explore and to

support decisions about the destinations for human exploration; and to

promote international and commercial participation in exploration to

further U.S. scientific, security, and economic interests.

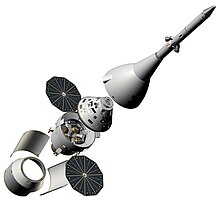

To this end, the President's Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy was formed by President Bush on January 27, 2004. Its final report was submitted on June 4, 2004. This led to the NASA Exploration Systems Architecture Study

in mid-2005, which developed technical plans for carrying out the

programs specified in the Vision for Space Exploration. This led to the

beginning of execution of Constellation program, including the Orion crew module, the Altair lunar lander, and the Ares I and Ares V rockets. The Ares I-X mission, a test launch of a prototype Ares I rocket, was successfully completed in October 2009.

A new National Space Policy was released on August 31, 2006 that

established overarching national policy that governs the conduct of U.S.

space activities. The document, the first full revision of overall

space policy in 10 years, emphasized security issues, encouraged private

enterprise in space, and characterized the role of U.S. space diplomacy

largely in terms of persuading other nations to support U.S. policy.

The United States National Security Council

said in written comments that an update was needed to "reflect the fact

that space has become an even more important component of U.S. Economic security, National security, and homeland security."

The Bush policy accepted current international agreements, but stated

that it "rejects any limitations on the fundamental right of the United

States to operate in and acquire data from space,"

and that "The United States will oppose the development of new legal

regimes or other restrictions that seek to prohibit or limit U.S. access

to or use of space."

Obama administration

The Obama administration commissioned the Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee in 2009 to review the human spaceflight

plans of the United States and to ensure the nation is on "a vigorous

and sustainable path to achieving its boldest aspirations in space,"

covering human spaceflight options after the time NASA plans to retire the Space Shuttle.

On April 15, 2010, President Obama spoke at the Kennedy Space Center announcing the administration's plans for NASA. None of the 3 plans outlined in the Committee's final report were completely selected. The President cancelled the Constellation program

and rejected immediate plans to return to the Moon on the premise that

the current plan had become nonviable. He instead promised $6 billion

in additional funding and called for development of a new heavy lift

rocket program to be ready for construction by 2015 with manned missions

to Mars orbit by the mid-2030s.

The Obama administration released its new formal space policy on June

28, 2010, in which it also reversed the Bush policy's rejection of

international agreements to curb the militarization of space, saying

that it would "consider proposals and concepts for arms control measures

if they are equitable, effectively verifiable and enhance the national

security of the United States and its allies."

The NASA Authorization Act of 2010, passed on October 11, 2010, enacted many of these space policy goals.

Trump administration

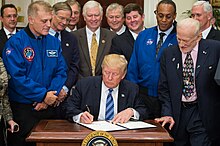

President

Trump signs an executive order re-establishing the National Space

Council, with astronauts Dave Wolf and Al Drew, and Apollo 11 astronaut

Buzz Aldrin (left-to-right) looking on.

On June 30, 2017, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to re-establish the National Space Council, chaired by Vice President Mike Pence.

The Trump administration's first budget request keeps Obama-era human

spaceflight programs in place: commercial spacecraft to ferry astronauts

to and from the International Space Station, the government-owned Space Launch System, and the Orion crew capsule for deep space missions, while reducing Earth science research and calling for the elimination of NASA's education office.

On December 11, 2017, President Trump signed Space Policy

Directive 1, a change in national space policy that provides for a

U.S.-led, integrated program with private sector partners for a human

return to the Moon, followed by missions to Mars and beyond. The

policy calls for the NASA administrator to "lead an innovative and

sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international

partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring

back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities." The effort will more

effectively organize government, private industry, and international

efforts toward returning humans on the Moon, and will lay the foundation

that will eventually enable human exploration of Mars.

The President stated "The directive I am signing today will

refocus America's space program on human exploration and discovery." "It

marks a first step in returning American astronauts to the Moon for the

first time since 1972, for long-term exploration and use. This time,

we will not only plant our flag and leave our footprints -- we will

establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars, and perhaps

someday, to many worlds beyond."

"Under President Trump's leadership, America will lead in space

once again on all fronts," said Vice President Pence. "As the President

has said, space is the 'next great American frontier' – and it is our

duty – and our destiny – to settle that frontier with American

leadership, courage, and values. The signing of this new directive is

yet another promise kept by President Trump."

Among other dignitaries on hand for the signing, were NASA astronauts Sen. Harrison "Jack" Schmitt, Buzz Aldrin, Peggy Whitson, and Christina Koch.

Schmitt landed on the Moon 45 years to the minute that the policy

directive was signed as part of NASA's Apollo 17 mission, and is the

most recent living person to have set foot on our lunar neighbor. Aldrin

was the second person to walk on the Moon during the Apollo 11 mission.

Whitson spoke to the president from space in April aboard the

International Space Station and while flying back home after breaking

the record for most time in space by a U.S. astronaut in September. Koch

is a member of NASA's astronaut class of 2013.