From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

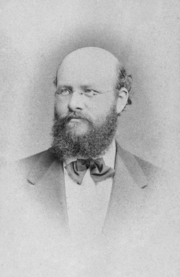

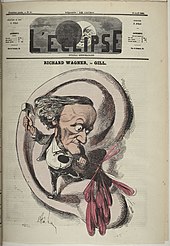

Richard Wagner in 1871

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (

VAHG-nər,

German: [ˈʁɪçaʁt ˈvaːɡnɐ] ( listen)

listen); 22 May 1813 – 13 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director,

polemicist,

and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his

mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most opera

composers, Wagner wrote both the

libretto and the music for each of his stage works. Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works in the

romantic vein of

Carl Maria von Weber and

Giacomo Meyerbeer, Wagner revolutionised opera through his concept of the

Gesamtkunstwerk

("total work of art"), by which he sought to synthesise the poetic,

visual, musical and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama. He

described this vision in a series of essays published between 1849 and

1852. Wagner realised these ideas most fully in the first half of the

four-opera cycle

Der Ring des Nibelungen (

The Ring of the Nibelung).

His compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex

textures, rich

harmonies and

orchestration, and the elaborate use of

leitmotifs—musical

phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot

elements. His advances in musical language, such as extreme

chromaticism and quickly shifting

tonal centres, greatly influenced the development of classical music. His

Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music.

Until his final years, Wagner's life was characterised by

political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty and repeated flight

from his creditors. His controversial writings on music, drama and

politics have attracted extensive comment, notably, since the late 20th

century, where they express

antisemitic

sentiments. The effect of his ideas can be traced in many of the arts

throughout the 20th century; his influence spread beyond composition

into conducting, philosophy, literature, the

visual arts and theatre.

Biography

Early years

Wagner's birthplace, at 3,

the Brühl, Leipzig

Richard Wagner was born to an

ethnic German family in

Leipzig, who lived at No 3, the

Brühl (

The House of the Red and White Lions) in the

Jewish quarter.He was

baptized at

St. Thomas Church.

He was the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, who was a clerk in the

Leipzig police service, and his wife, Johanna Rosine (née Paetz), the

daughter of a baker. Wagner's father Carl died of

typhus six months after Richard's birth. Afterwards, his mother Johanna lived with Carl's friend, the actor and playwright

Ludwig Geyer.

In August 1814 Johanna and Geyer probably married—although no

documentation of this has been found in the Leipzig church registers. She and her family moved to Geyer's residence in

Dresden.

Until he was fourteen, Wagner was known as Wilhelm Richard Geyer. He

almost certainly thought that Geyer was his biological father.

Geyer's love of the theatre came to be shared by his stepson, and Wagner took part in his performances. In his autobiography

Mein Leben Wagner recalled once playing the part of an angel.

In late 1820, Wagner was enrolled at Pastor Wetzel's school at

Possendorf, near Dresden, where he received some piano instruction from

his Latin teacher. He struggled to play a proper

scale at the keyboard and preferred playing theatre overtures

by ear. Following Geyer's death in 1821, Richard was sent to the

Kreuzschule, the boarding school of the

Dresdner Kreuzchor, at the expense of Geyer's brother. At the age of nine he was hugely impressed by the

Gothic elements of

Carl Maria von Weber's opera

Der Freischütz, which he saw Weber conduct. At this period Wagner entertained ambitions as a playwright. His first creative effort, listed in the

Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis (the standard listing of Wagner's works) as WWV 1, was a tragedy called

Leubald. Begun when he was in school in 1826, the play was strongly influenced by

Shakespeare and

Goethe. Wagner was determined to set it to music and persuaded his family to allow him music lessons.

By 1827, the family had returned to Leipzig. Wagner's first lessons in

harmony were taken during 1828–31 with Christian Gottlieb Müller. In January 1828 he first heard

Beethoven's

7th Symphony and then, in March, the same composer's

9th Symphony (both at the

Gewandhaus). Beethoven became a major inspiration, and Wagner wrote a piano transcription of the 9th Symphony. He was also greatly impressed by a performance of

Mozart's

Requiem. Wagner's early

piano sonatas and his first attempts at orchestral

overtures date from this period.

In 1829 he saw a performance by

dramatic soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, and she became his ideal of the fusion of drama and music in opera. In

Mein Leben,

Wagner wrote, "When I look back across my entire life I find no event

to place beside this in the impression it produced on me," and claimed

that the "profoundly human and ecstatic performance of this incomparable

artist" kindled in him an "almost demonic fire."

In 1831, Wagner enrolled at the

Leipzig University, where he became a member of the Saxon

student fraternity. He took composition lessons with the

Thomaskantor Theodor Weinlig.

Weinlig was so impressed with Wagner's musical ability that he refused

any payment for his lessons. He arranged for his pupil's Piano Sonata in

B-flat major (which was consequently dedicated to him) to be published

as Wagner's Op. 1. A year later, Wagner composed his

Symphony in C major, a Beethovenesque work performed in Prague in 1832

[20] and at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1833. He then began to work on an opera,

Die Hochzeit (

The Wedding), which he never completed.

Early career and marriage (1833–1842)

In 1833, Wagner's brother Albert managed to obtain for him a position as choirmaster at the theatre in

Würzburg. In the same year, at the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera,

Die Feen (

The Fairies). This work, which imitated the style of Weber, went unproduced until half a century later, when it was premiered in

Munich shortly after the composer's death in 1883.

Having returned to Leipzig in 1834, Wagner held a brief appointment as musical director at the opera house in

Magdeburg during which he wrote

Das Liebesverbot (

The Ban on Love), based on Shakespeare's

Measure for Measure.

This was staged at Magdeburg in 1836 but closed before the second

performance; this, together with the financial collapse of the theatre

company employing him, left the composer in bankruptcy. Wagner had fallen for one of the leading ladies at Magdeburg, the actress

Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer and after the disaster of

Das Liebesverbot he followed her to

Königsberg, where she helped him to get an engagement at the theatre. The two married in

Tragheim Church on 24 November 1836. In May 1837, Minna left Wagner for another man, and this was but only the first débâcle of a tempestuous marriage. In June 1837, Wagner moved to

Riga (then in the

Russian Empire), where he became music director of the local opera;

having in this capacity engaged Minna's sister Amalie (also a singer)

for the theatre, he presently resumed relations with Minna during 1838.

By 1839, the couple had amassed such large debts that they fled Riga on the run from creditors. Debts would plague Wagner for most of his life. Initially they took a stormy sea passage to London,

[36] from which Wagner drew the inspiration for his opera

Der fliegende Holländer (

The Flying Dutchman), with a plot based on a sketch by

Heinrich Heine. The Wagners settled in Paris in September 1839 and stayed there until 1842. Wagner made a scant living by writing articles and short novelettes such as

A pilgrimage to Beethoven, which sketched his growing concept of "music drama", and

An end in Paris, where he depicts his own miseries as a German musician in the French metropolis. He also provided arrangements of operas by other composers, largely on behalf of the

Schlesinger publishing house. During this stay he completed his third and fourth operas

Rienzi and

Der fliegende Holländer.

Dresden (1842–1849)

Wagner c. 1840, by Ernest Benedikt Kietz

Wagner had completed

Rienzi in 1840. With the strong support of

Giacomo Meyerbeer, it was accepted for performance by the Dresden

Court Theatre (

Hofoper) in the

Kingdom of Saxony and in 1842, Wagner moved to Dresden. His relief at returning to Germany was recorded in his "

Autobiographic Sketch" of 1842, where he wrote that, en route from Paris, "For the first time I saw the

Rhine—with hot tears in my eyes, I, poor artist, swore eternal fidelity to my German fatherland."

Rienzi was staged to considerable acclaim on 20 October.

Wagner lived in Dresden for the next six years, eventually being appointed the Royal Saxon Court Conductor. During this period, he staged there

Der fliegende Holländer (2 January 1843) and

Tannhäuser (19 October 1845), the first two of his three middle-period operas. Wagner also mixed with artistic circles in Dresden, including the composer

Ferdinand Hiller and the architect

Gottfried Semper.

In exile: Switzerland (1849–1858)

Warrant for the arrest of Richard Wagner, issued on 16 May 1849

Wagner was to spend the next twelve years in exile from Germany. He had completed

Lohengrin, the last of his middle-period operas, before the Dresden uprising, and now wrote desperately to his friend

Franz Liszt to have it staged in his absence. Liszt conducted the premiere in

Weimar in August 1850.

Nevertheless, Wagner was in grim personal straits, isolated from

the German musical world and without any regular income. In 1850, Julie,

the wife of his friend Karl Ritter, began to pay him a small pension

which she maintained until 1859. With help from her friend Jessie

Laussot, this was to have been augmented to an annual sum of 3,000

Thalers

per year; but this plan was abandoned when Wagner began an affair with

Mme. Laussot. Wagner even planned an elopement with her in 1850, which

her husband prevented. Meanwhile, Wagner's wife Minna, who had disliked the operas he had written after

Rienzi, was falling into a deepening

depression. Wagner fell victim to ill-health, according to

Ernest Newman "largely a matter of overwrought nerves", which made it difficult for him to continue writing.

Wagner's primary published output during his first years in Zürich was a set of essays. In "

The Artwork of the Future" (1849), he described a vision of opera as

Gesamtkunstwerk ("total work of art"), in which the various arts such as music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts and stagecraft were unified. "

Judaism in Music" (1850) was the first of Wagner's writings to feature

antisemitic views.

In this polemic Wagner argued, frequently using traditional antisemitic

abuse, that Jews had no connection to the German spirit, and were thus

capable of producing only shallow and artificial music. According to

him, they composed music to achieve popularity and, thereby, financial

success, as opposed to creating genuine works of art.

In "

Opera and Drama" (1851), Wagner described the

aesthetics of drama that he was using to create the

Ring operas. Before leaving Dresden, Wagner had drafted a scenario that eventually became the four-opera cycle

Der Ring des Nibelungen. He initially

wrote the libretto for a single opera,

Siegfrieds Tod (

Siegfried's Death), in 1848. After arriving in Zürich, he expanded the story with the opera

Der junge Siegfried (

Young Siegfried), which explored the

hero's background. He completed the text of the cycle by writing the libretti for

Die Walküre (

The Valkyrie) and

Das Rheingold (

The Rhine Gold) and revising the other libretti to agree with his new concept, completing them in 1852.

The concept of opera expressed in "Opera and Drama" and in other essays

effectively renounced the operas he had previously written, up to and

including

Lohengrin. Partly in an attempt to explain his change of views, Wagner published in 1851 the autobiographical "

A Communication to My Friends". This contained his first public announcement of what was to become the

Ring cycle:

I shall never write an Opera more. As I have no wish to invent an arbitrary title for my works, I will call them Dramas ...

I propose to produce my myth in three complete dramas, preceded by a lengthy Prelude (Vorspiel). ...

At a specially-appointed Festival, I propose, some future time, to produce those three Dramas with their Prelude, in the course of three days and a fore-evening [emphasis in original].

Wagner began composing the music for

Das Rheingold between November 1853 and September 1854, following it immediately with

Die Walküre (written between June 1854 and March 1856). He began work on the third

Ring opera, which he now called simply

Siegfried,

probably in September 1856, but by June 1857 he had completed only the

first two acts. He decided to put the work aside to concentrate on a new

idea:

Tristan und Isolde, based on the

Arthurian love story

Tristan and Iseult.

One source of inspiration for

Tristan und Isolde was the philosophy of

Arthur Schopenhauer, notably his

The World as Will and Representation, to which Wagner had been introduced in 1854 by his poet friend

Georg Herwegh. Wagner later called this the most important event of his life.

His personal circumstances certainly made him an easy convert to what

he understood to be Schopenhauer's philosophy, a deeply pessimistic view

of the human condition. He remained an adherent of Schopenhauer for the

rest of his life.

One of Schopenhauer's doctrines was that music held a supreme

role in the arts as a direct expression of the world's essence, namely,

blind, impulsive will.

This doctrine contradicted Wagner's view, expressed in "Opera and

Drama", that the music in opera had to be subservient to the drama.

Wagner scholars have argued that Schopenhauer's influence caused Wagner

to assign a more commanding role to music in his later operas, including

the latter half of the Ring cycle, which he had yet to compose. Aspects of Schopenhauerian doctrine found their way into Wagner's subsequent libretti.

A second source of inspiration was Wagner's infatuation with the poet-writer

Mathilde Wesendonck,

the wife of the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck. Wagner met the

Wesendoncks, who were both great admirers of his music, in Zürich in

1852. From May 1853 onwards Wesendonck made several loans to Wagner to

finance his household expenses in Zürich, and in 1857 placed a cottage on his estate at Wagner's disposal, which became known as the

Asyl

("asylum" or "place of rest"). During this period, Wagner's growing

passion for his patron's wife inspired him to put aside work on the

Ring cycle (which was not resumed for the next twelve years) and begin work on

Tristan. While planning the opera, Wagner composed the

Wesendonck Lieder,

five songs for voice and piano, setting poems by Mathilde. Two of these

settings are explicitly subtitled by Wagner as "studies for

Tristan und Isolde".

Amongst the conducting engagements that Wagner undertook for

revenue during this period, he gave several concerts in 1855 with the

Philharmonic Society of London, including one before

Queen Victoria. The Queen enjoyed his

Tannhäuser

overture and spoke with Wagner after the concert, writing of him in her

diary that he was "short, very quiet, wears spectacles & has a very

finely-developed forehead, a hooked nose & projecting chin."

In exile: Venice and Paris (1858–1862)

Wagner's uneasy affair with Mathilde collapsed in 1858, when Minna intercepted a letter to Mathilde from him. After the resulting confrontation with Minna, Wagner left Zürich alone, bound for

Venice, where he rented an apartment in the

Palazzo Giustinian, while Minna returned to Germany.

Wagner's attitude to Minna had changed; the editor of his

correspondence with her, John Burk, has said that she was to him "an

invalid, to be treated with kindness and consideration, but, except at a

distance, [was] a menace to his peace of mind."

Wagner continued his correspondence with Mathilde and his friendship

with her husband Otto, who maintained his financial support of the

composer. In an 1859 letter to Mathilde, Wagner wrote, half-satirically,

of

Tristan: "Child! This Tristan is turning into something

terrible.

This final act!!!—I fear the opera will be banned ... only mediocre

performances can save me! Perfectly good ones will be bound to drive

people mad."

In November 1859, Wagner once again moved to Paris to oversee production of a new revision of

Tannhäuser, staged thanks to the efforts of Princess

Pauline von Metternich, whose husband was the Austrian ambassador in Paris. The performances of the Paris

Tannhäuser in 1861 were

a notable fiasco. This was partly a consequence of the conservative tastes of the

Jockey Club,

which organised demonstrations in the theatre to protest at the

presentation of the ballet feature in act 1 (instead of its traditional

location in the second act); but the opportunity was also exploited by

those who wanted to use the occasion as a veiled political protest

against the pro-Austrian policies of

Napoleon III. It was during this visit that Wagner met the French poet

Charles Baudelaire, who wrote an appreciative brochure, "

Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser à Paris". The opera was withdrawn after the third performance and Wagner left Paris soon after.

He had sought a reconciliation with Minna during this Paris visit, and

although she joined him there, the reunion was not successful and they

again parted from each other when Wagner left.

Return and resurgence (1862–1871)

The

political ban that had been placed on Wagner in Germany after he had

fled Dresden was fully lifted in 1862. The composer settled in

Biebrich, on the Rhine near Wiesbaden in

Hesse. Here Minna visited him for the last time: they parted irrevocably, though Wagner continued to give financial support to her while she lived in Dresden until her death in 1866.

In Biebrich, Wagner at last began work on

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, his only mature comedy. Wagner wrote a first draft of the libretto in 1845, and he had resolved to develop it during a visit he had made to Venice with the Wesendoncks in 1860, where he was inspired by

Titian's painting

The Assumption of the Virgin. Throughout this period (1861–64) Wagner sought to have

Tristan und Isolde produced in Vienna.

Despite numerous rehearsals, the opera remained unperformed, and gained

a reputation as being "impossible" to sing, which added to Wagner's

financial problems.

Wagner's fortunes took a dramatic upturn in 1864, when

King Ludwig II succeeded to the throne of

Bavaria at the age of 18. The young king, an ardent admirer of Wagner's operas, had the composer brought to Munich. The King, who was homosexual, expressed in his correspondence a passionate personal adoration for the composer, and Wagner in his responses had no scruples about counterfeiting a similar atmosphere. Ludwig settled Wagner's considerable debts, and proposed to stage

Tristan,

Die Meistersinger, the

Ring, and the other operas Wagner planned. Wagner also began to dictate his autobiography,

Mein Leben, at the King's request.

Wagner noted that his rescue by Ludwig coincided with news of the death

of his earlier mentor (but later supposed enemy) Giacomo Meyerbeer, and

regretted that "this operatic master, who had done me so much harm,

should not have lived to see this day."

After grave difficulties in rehearsal,

Tristan und Isolde premiered at the

National Theatre Munich

on 10 June 1865, the first Wagner opera premiere in almost 15 years.

(The premiere had been scheduled for 15 May, but was delayed by bailiffs

acting for Wagner's creditors, and also because the Isolde,

Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld, was hoarse and needed time to recover.) The conductor of this premiere was

Hans von Bülow, whose wife,

Cosima, had given birth in April that year to a daughter, named Isolde, a child not of Bülow but of Wagner.

Cosima was 24 years younger than Wagner and was herself illegitimate, the daughter of the Countess

Marie d'Agoult, who had left her husband for

Franz Liszt. Liszt initially disapproved of his daughter's involvement with Wagner, though nevertheless, the two men were friends.

The indiscreet affair scandalised Munich, and Wagner also fell into

disfavour with many leading members of the court, who were suspicious of

his influence on the King. In December 1865, Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich. He apparently also toyed with the idea of abdicating to follow his hero into exile, but Wagner quickly dissuaded him.

Richard and Cosima Wagner, photographed in 1872

Ludwig installed Wagner at the Villa

Tribschen, beside Switzerland's

Lake Lucerne.

Die Meistersinger was completed at Tribschen in 1867, and premiered in Munich on 21 June the following year. At Ludwig's insistence, "special previews" of the first two works of the

Ring,

Das Rheingold and

Die Walküre, were performed at Munich in 1869 and 1870,

but Wagner retained his dream, first expressed in "A Communication to

My Friends", to present the first complete cycle at a special festival

with a new, dedicated,

opera house.

Minna had died of a heart attack on 25 January 1866 in Dresden. Wagner did not attend the funeral.

Following Minna's death Cosima wrote to Hans von Bülow on a number of

occasions asking him to grant her a divorce, but Bülow refused to

concede this. He only consented after she had two more children with

Wagner; another daughter, named Eva, after the heroine of

Meistersinger, and a son

Siegfried, named for the hero of the

Ring. The divorce was finally sanctioned, after delays in the legal process, by a Berlin court on 18 July 1870. Richard and Cosima's wedding took place on 25 August 1870. On Christmas Day of that year, Wagner arranged a surprise performance (its premiere) of the

Siegfried Idyll for Cosima's birthday. The marriage to Cosima lasted to the end of Wagner's life.

Wagner, settled into his new-found domesticity, turned his energies towards completing the Ring

cycle. He had not abandoned polemics: he republished his 1850 pamphlet

"Judaism in Music", originally issued under a pseudonym, under his own

name in 1869. He extended the introduction, and wrote a lengthy

additional final section. The publication led to several public protests

at early performances of Die Meistersinger in Vienna and Mannheim.

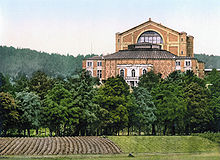

Bayreuth (1871–1876)

In 1871, Wagner decided to move to

Bayreuth, which was to be the location of his new opera house.

The town council donated a large plot of land—the "Green Hill"—as a

site for the theatre. The Wagners moved to the town the following year,

and the foundation stone for the

Bayreuth Festspielhaus ("Festival Theatre") was laid. Wagner initially announced the first Bayreuth Festival, at which for the first time the

Ring cycle would be presented complete, for 1873,

but since Ludwig had declined to finance the project, the start of

building was delayed and the proposed date for the festival was

deferred. To raise funds for the construction, "

Wagner societies" were formed in several cities, and Wagner began touring Germany conducting concerts.

By the spring of 1873, only a third of the required funds had been

raised; further pleas to Ludwig were initially ignored, but early in

1874, with the project on the verge of collapse, the King relented and

provided a loan. The full building programme included the family home, "

Wahnfried", into which Wagner, with Cosima and the children, moved from their temporary accommodation on 18 April 1874.

The theatre was completed in 1875, and the festival scheduled for the

following year. Commenting on the struggle to finish the building,

Wagner remarked to Cosima: "Each stone is red with my blood and yours".

For the design of the Festspielhaus, Wagner appropriated some of the

ideas of his former colleague, Gottfried Semper, which he had previously

solicited for a proposed new opera house at Munich.

Wagner was responsible for several theatrical innovations at Bayreuth;

these include darkening the auditorium during performances, and placing

the orchestra in a pit out of view of the audience.

The Festspielhaus finally opened on 13 August 1876 with

Das Rheingold, at last taking its place as the first evening of the complete

Ring cycle; the 1876

Bayreuth Festival therefore saw the premiere of the complete cycle, performed as a sequence as the composer had intended. The 1876 Festival consisted of three full

Ring cycles (under the baton of

Hans Richter). At the end, critical reactions ranged between that of the Norwegian composer

Edvard Grieg, who thought the work "divinely composed", and that of the French newspaper

Le Figaro, which called the music "the dream of a lunatic". Amongst the disillusioned were Wagner's friend and disciple

Friedrich Nietzsche, who, having published his eulogistic essay "Richard Wagner in Bayreuth" before the festival as part of his

Untimely Meditations,

was bitterly disappointed by what he saw as Wagner's pandering to

increasingly exclusivist German nationalism; his breach with Wagner

began at this time. The festival firmly established Wagner as an artist of European, and indeed world, importance: attendees included

Kaiser Wilhelm I, the Emperor

Pedro II of Brazil,

Anton Bruckner,

Camille Saint-Saëns and

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Wagner was far from satisfied with the Festival; Cosima recorded

that months later, his attitude towards the productions was "Never

again, never again!" Moreover, the festival finished with a deficit of about 150,000 marks. The expenses of Bayreuth and of

Wahnfried meant that Wagner still sought additional sources of income by conducting or taking on commissions such as the

Centennial March for America, for which he received $5000.

Last years (1876–1883)

Following the first Bayreuth Festival, Wagner began work on

Parsifal, his final opera. The composition took four years, much of which Wagner spent in Italy for health reasons. From 1876 to 1878 Wagner also embarked on the last of his documented emotional liaisons, this time with

Judith Gautier, whom he had met at the 1876 Festival. Wagner was also much troubled by problems of financing

Parsifal,

and by the prospect of the work being performed by other theatres than

Bayreuth. He was once again assisted by the liberality of King Ludwig,

but was still forced by his personal financial situation in 1877 to sell

the rights of several of his unpublished works (including the

Siegfried Idyll) to the publisher

Schott.

The Wagner grave in the Wahnfried garden; in 1977 Cosima's ashes were placed alongside Wagner's body

Wagner wrote a number of articles in his later years, often on political topics, and often

reactionary

in tone, repudiating some of his earlier, more liberal, views. These

include "Religion and Art" (1880) and "Heroism and Christianity" (1881),

which were printed in the journal

Bayreuther Blätter, published by his supporter

Hans von Wolzogen. Wagner's sudden interest in Christianity at this period, which infuses

Parsifal, was contemporary with his increasing alignment with

German nationalism,

and required on his part, and the part of his associates, "the

rewriting of some recent Wagnerian history", so as to represent, for

example, the

Ring as a work reflecting Christian ideals. Many of these later articles, including "What is German?" (1878, but based on a draft written in the 1860s), repeated Wagner's antisemitic preoccupations.

Wagner completed

Parsifal in January 1882, and a second Bayreuth Festival was held for the new opera, which premiered on 26 May. Wagner was by this time extremely ill, having suffered a series of increasingly severe

angina attacks. During the sixteenth and final performance of

Parsifal on 29 August, he entered the pit unseen during act 3, took the baton from conductor

Hermann Levi, and led the performance to its conclusion.

After the festival, the Wagner family journeyed to Venice for the

winter. Wagner died of a heart attack at the age of 69 on 13 February

1883 at

Ca' Vendramin Calergi, a 16th-century

palazzo on the

Grand Canal. The legend that the attack was prompted by argument with Cosima over Wagner's supposedly amorous interest in the singer , who had been a Flower-maiden in

Parsifal at Bayreuth, is without credible evidence. After a funerary

gondola

bore Wagner's remains over the Grand Canal, his body was taken to

Germany where it was buried in the garden of the Villa Wahnfried in

Bayreuth.

Works

Wagner's musical output is listed by the

Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis (WWV) as comprising 113 works, including fragments and projects. The first complete scholarly edition of his musical works in print was commenced in 1970 under the aegis of the

Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts and the

Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur of

Mainz, and is presently under the editorship of

Egon Voss.

It will consist of 21 volumes (57 books) of music and 10 volumes (13

books) of relevant documents and texts. As at October 2017, three

volumes remain to be published. The publisher is

Schott Music.

Operas

Wagner's operatic works are his primary artistic legacy. Unlike most

opera composers, who generally left the task of writing the

libretto (the text and lyrics) to others, Wagner wrote his own libretti, which he referred to as "poems".

From 1849 onwards, he urged a new concept of opera often referred to as "music drama" (although he later rejected this term), in which all musical, poetic and dramatic elements were to be fused together—the

Gesamtkunstwerk.

Wagner developed a compositional style in which the importance of the

orchestra is equal to that of the singers. The orchestra's dramatic role

in the later operas includes the use of

leitmotifs,

musical phrases that can be interpreted as announcing specific

characters, locales, and plot elements; their complex interweaving and

evolution illuminates the progression of the drama. These operas are still, despite Wagner's reservations, referred to by many writers as "music dramas".

Early works (to 1842)

Wagner's earliest attempts at opera were often uncompleted. Abandoned works include

a pastoral opera based on

Goethe's

Die Laune des Verliebten (

The Infatuated Lover's Caprice), written at the age of 17,

Die Hochzeit (

The Wedding), on which Wagner worked in 1832, and the

singspiel Männerlist größer als Frauenlist (

Men are More Cunning than Women, 1837–38).

Die Feen (

The Fairies, 1833) was not performed in the composer's lifetime and

Das Liebesverbot (

The Ban on Love, 1836) was withdrawn after its first performance.

Rienzi (1842) was Wagner's first opera to be successfully staged. The compositional style of these early works was conventional—the relatively more sophisticated

Rienzi showing the clear influence of

Grand Opera à la

Spontini and Meyerbeer—and did not exhibit the innovations that would

mark Wagner's place in musical history. Later in life, Wagner said that

he did not consider these works to be part of his

oeuvre; and they have been performed only rarely in the last hundred years, although the overture to

Rienzi is an occasional concert-hall piece.

Die Feen,

Das Liebesverbot, and

Rienzi were performed at both Leipzig and Bayreuth in 2013 to mark the composer's bicentenary.

"Romantic operas" (1843–51)

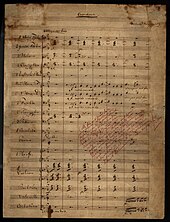

Opening of overture to Der fliegende Holländer in Wagner's hand and with his notes to the publisher

Wagner's middle stage output began with

Der fliegende Holländer (

The Flying Dutchman, 1843), followed by

Tannhäuser (1845) and

Lohengrin (1850). These three operas are sometimes referred to as Wagner's "romantic operas". They reinforced the reputation, among the public in Germany and beyond, that Wagner had begun to establish with

Rienzi. Although distancing himself from the style of these operas from 1849 onwards, he nevertheless reworked both

Der fliegende Holländer and

Tannhäuser on several occasions.

These three operas are considered to represent a significant

developmental stage in Wagner's musical and operatic maturity as regards

thematic handling, portrayal of emotions and orchestration. They are the earliest works included in the

Bayreuth canon, the mature operas that Cosima staged at the Bayreuth Festival after Wagner's death in accordance with his wishes. All three (including the differing versions of

Der fliegende Holländer and

Tannhäuser) continue to be regularly performed throughout the world, and have been frequently recorded. They were also the operas by which his fame spread during his lifetime.

"Music dramas" (1851–82)

Starting the Ring

The first two components of the

Ring cycle were

Das Rheingold (

The Rhinegold), which was completed in 1854, and

Die Walküre (

The Valkyrie), which was finished in 1856. In

Das Rheingold, with its "relentlessly talky 'realism' [and] the absence of lyrical '

numbers'", Wagner came very close to the musical ideals of his 1849–51 essays.

Die Walküre, which contains what is virtually a traditional

aria (Siegmund's

Winterstürme in the first act), and the quasi-

choral

appearance of the Valkyries themselves, shows more "operatic" traits,

but has been assessed by Barry Millington as "the music drama that most

satisfactorily embodies the theoretical principles of 'Oper und

Drama'... A thoroughgoing synthesis of poetry and music is achieved

without any notable sacrifice in musical expression."

Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger

While composing the opera

Siegfried, the third part of the

Ring cycle, Wagner interrupted work on it and between 1857 and 1864 wrote the tragic love story

Tristan und Isolde and his only mature comedy

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (

The Mastersingers of Nuremberg), two works that are also part of the regular operatic canon.

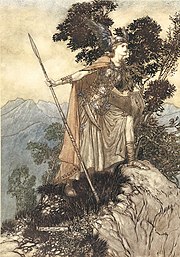

Franz Betz, who created the role of Hans Sachs in

Die Meistersinger, and sang Wotan in the first complete

Ring cycle

Tristan is often granted a special place in musical history; many see it as the beginning of the move away from conventional

harmony and

tonality and consider that it lays the groundwork for the direction of classical music in the 20th century.

Wagner felt that his musico-dramatical theories were most perfectly

realised in this work with its use of "the art of transition" between

dramatic elements and the balance achieved between vocal and orchestral

lines. Completed in 1859, the work was given its first performance in Munich, conducted by Bülow, in June 1865.

Die Meistersinger was originally conceived by Wagner in 1845 as a sort of comic pendant to

Tannhäuser. Like

Tristan, it was premiered in Munich under the baton of Bülow, on 21 June 1868, and became an immediate success. Barry Millington describes

Meistersinger as "a rich, perceptive music drama widely admired for its warm humanity"; but because of its strong German

nationalist overtones, it is also cited by some as an example of Wagner's reactionary politics and antisemitism.

Completing the Ring

When Wagner returned to writing the music for the last act of

Siegfried and for

Götterdämmerung (

Twilight of the Gods), as the final part of the

Ring, his style had changed once more to something more recognisable as "operatic" than the aural world of

Rheingold and

Walküre, though it was still thoroughly stamped with his own originality as a composer and suffused with leitmotifs. This was in part because the libretti of the four

Ring operas had been written in reverse order, so that the book for

Götterdämmerung was conceived more "traditionally" than that of

Rheingold; still, the self-imposed strictures of the

Gesamtkunstwerk had become relaxed. The differences also result from Wagner's development as a composer during the period in which he wrote

Tristan,

Meistersinger and the Paris version of

Tannhäuser. From act 3 of

Siegfried onwards, the

Ring becomes more

chromatic melodically, more complex harmonically and more developmental in its treatment of leitmotifs.

Wagner took 26 years from writing the first draft of a libretto in 1848 until he completed Götterdämmerung in 1874. The Ring takes about 15 hours to perform and is the only undertaking of such size to be regularly presented on the world's stages.

Parsifal

Wagner's final opera,

Parsifal (1882), which was his only work written especially for his Bayreuth Festspielhaus and which is described in the score as a "

Bühnenweihfestspiel" ("festival play for the consecration of the stage"), has a storyline suggested by elements of the legend of the

Holy Grail. It also carries elements of

Buddhist renunciation suggested by Wagner's readings of Schopenhauer. Wagner described it to Cosima as his "last card".

It remains controversial because of its treatment of Christianity, its

eroticism, and its expression, as perceived by some commentators, of

German nationalism and antisemitism. Despite the composer's own description of the opera to King Ludwig as "this most Christian of works", Ulrike Kienzle has commented that "Wagner's turn to Christian mythology, upon which the imagery and spiritual contents of

Parsifal rest, is idiosyncratic and contradicts Christian

dogma in many ways."

Musically the opera has been held to represent a continuing development

of the composer's style, and Barry Millington describes it as "a

diaphanous score of unearthly beauty and refinement".

Non-operatic music

Apart from his operas, Wagner composed relatively few pieces of music. These include a

symphony in C major (written at the age of 19), the

Faust Overture (the only completed part of an intended symphony on the subject), some

concert overtures, and choral and piano pieces. His most commonly performed work that is not an extract from an opera is the

Siegfried Idyll for chamber orchestra, which has several motifs in common with the

Ring cycle. The

Wesendonck Lieder are also often performed, either in the original piano version, or with orchestral accompaniment. More rarely performed are the

American Centennial March (1876), and

Das Liebesmahl der Apostel (

The Love Feast of the Apostles), a piece for male choruses and orchestra composed in 1843 for the city of Dresden.

After completing

Parsifal, Wagner expressed his intention to turn to the writing of symphonies, and several sketches dating from the late 1870s and early 1880s have been identified as work towards this end.

The overtures and certain orchestral passages from Wagner's middle and

late-stage operas are commonly played as concert pieces. For most of

these, Wagner wrote or rewrote short passages to ensure musical

coherence. The "

Bridal Chorus" from

Lohengrin is frequently played as the bride's processional

wedding march in English-speaking countries.

Prose writings

Wagner was an extremely prolific writer, authoring numerous books,

poems, and articles, as well as voluminous correspondence. His writings

covered a wide range of topics, including autobiography, politics,

philosophy, and detailed analyses of his own operas.

Wagner planned for a collected edition of his publications as early as 1865; he believed that such an edition would help the world understand his intellectual development and artistic aims.

The first such edition was published between 1871 and 1883, but was

doctored to suppress or alter articles that were an embarrassment to him

(e.g. those praising Meyerbeer), or by altering dates on some articles

to reinforce Wagner's own account of his progress. Wagner's autobiography Mein Leben

was originally published for close friends only in a very small edition

(15–18 copies per volume) in four volumes between 1870 and 1880. The

first public edition (with many passages suppressed by Cosima) appeared

in 1911; the first attempt at a full edition (in German) appeared in

1963.

There have been modern complete or partial editions of Wagner's writings, including a centennial edition in German edited by

Dieter Borchmeyer (which, however, omitted the essay "Das Judenthum in der Musik" and

Mein Leben).

The English translations of Wagner's prose in eight volumes by W.

Ashton Ellis (1892–99) are still in print and commonly used, despite

their deficiencies.

The first complete historical and critical edition of Wagner's prose

works was launched in 2013 at the Institute for Music Research at the

University of Würzburg;

this will result in 16 volumes (eight of text and eight of commentary)

totalling approximately 5,300 pages. It is anticipated that the project

will be completed by 2030.

A complete edition of Wagner's correspondence, estimated to

amount to between 10,000 and 12,000 items, is under way under the

supervision of the University of Würzburg. As of October 2017, 23

volumes have appeared, covering the period to 1873.

Influence and legacy

Influence on music

Wagner's later musical style introduced new ideas in harmony, melodic process (leitmotif) and operatic structure. Notably from

Tristan und Isolde

onwards, he explored the limits of the traditional tonal system, which

gave keys and chords their identity, pointing the way to

atonality in the 20th century. Some music historians date the beginning of

modern classical music to the first notes of

Tristan, which include the so-called

Tristan chord.

Wagner inspired great devotion. For a long period, many composers

were inclined to align themselves with or against Wagner's music.

Anton Bruckner and

Hugo Wolf were greatly indebted to him, as were

César Franck,

Henri Duparc,

Ernest Chausson,

Jules Massenet,

Richard Strauss,

Alexander von Zemlinsky,

Hans Pfitzner and numerous others.

Gustav Mahler was devoted to Wagner and his music; aged 15, he sought him out on his 1875 visit to Vienna, became a renowned Wagner conductor, and his compositions are seen by

Richard Taruskin as extending Wagner's "maximalization" of "the temporal and the sonorous" in music to the world of the symphony. The harmonic revolutions of

Claude Debussy and

Arnold Schoenberg (both of whose

oeuvres contain examples of tonal and

atonal modernism) have often been traced back to

Tristan and

Parsifal. The Italian form of operatic

realism known as

verismo owed much to the Wagnerian concept of musical form.

Wagner made a major contribution to the principles and practice of conducting. His essay "About Conducting" (1869) advanced

Hector Berlioz's

technique of conducting and claimed that conducting was a means by

which a musical work could be re-interpreted, rather than simply a

mechanism for achieving orchestral unison. He exemplified this approach

in his own conducting, which was significantly more flexible than the

disciplined approach of

Felix Mendelssohn; in his view this also justified practices that would today be frowned upon, such as the rewriting of scores.

Wilhelm Furtwängler

felt that Wagner and Bülow, through their interpretative approach,

inspired a whole new generation of conductors (including Furtwängler

himself).

Amongst those claiming inspiration from Wagner's music are the German band

Rammstein, and the electronic composer

Klaus Schulze, whose 1975 album

Timewind consists of two 30-minute tracks,

Bayreuth Return and

Wahnfried 1883.

Joey DeMaio of the band

Manowar has described Wagner as "The father of

heavy metal". The

Slovenian group

Laibach created the 2009 suite

VolksWagner, using material from Wagner's operas.

Phil Spector's

Wall of Sound recording technique was, it has been claimed, heavily influenced by Wagner.

Influence on literature, philosophy and the visual arts

Wagner's influence on literature and philosophy is significant. Millington has commented:

[Wagner's] protean abundance meant that he could inspire the use of literary motif in many a novel employing interior monologue; ... the Symbolists saw him as a mystic hierophant; the Decadents found many a frisson in his work.

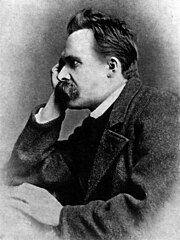

Friedrich Nietzsche was a member of Wagner's inner circle during the early 1870s, and his first published work,

The Birth of Tragedy, proposed Wagner's music as the

Dionysian "rebirth" of European culture in opposition to

Apollonian

rationalist "decadence". Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the

first Bayreuth Festival, believing that Wagner's final phase represented

a pandering to Christian pieties and a surrender to the new

German Reich. Nietzsche expressed his displeasure with the later Wagner in "

The Case of Wagner" and "

Nietzsche contra Wagner".

The poets

Charles Baudelaire,

Stéphane Mallarmé and

Paul Verlaine worshipped Wagner.

Édouard Dujardin, whose influential novel

Les Lauriers sont coupés is in the form of an interior monologue inspired by Wagnerian music, founded a journal dedicated to Wagner,

La Revue Wagnérienne, to which

J. K. Huysmans and

Téodor de Wyzewa contributed. In a list of major cultural figures influenced by Wagner,

Bryan Magee includes

D. H. Lawrence,

Aubrey Beardsley,

Romain Rolland,

Gérard de Nerval,

Pierre-Auguste Renoir,

Rainer Maria Rilke and numerous others.

In the 20th century,

W. H. Auden once called Wagner "perhaps the greatest genius that ever lived", while

Thomas Mann and

Marcel Proust were heavily influenced by him and discussed Wagner in their novels. He is also discussed in some of the works of

James Joyce. Wagnerian themes inhabit

T. S. Eliot's

The Waste Land, which contains lines from

Tristan und Isolde and

Götterdämmerung, and Verlaine's poem on

Parsifal.

Many of Wagner's concepts, including his speculation about dreams, predated their investigation by

Sigmund Freud.

Wagner had publicly analysed the Oedipus myth before Freud was born in

terms of its psychological significance, insisting that incestuous

desires are natural and normal, and perceptively exhibiting the

relationship between sexuality and anxiety.

Georg Groddeck considered the

Ring as the first manual of psychoanalysis.

Influence on cinema

Opponents and supporters

Not all reaction to Wagner was positive. For a time, German musical

life divided into two factions, supporters of Wagner and supporters of

Johannes Brahms; the latter, with the support of the powerful critic

Eduard Hanslick (of whom Beckmesser in

Meistersinger is in part a caricature) championed traditional forms and led the conservative front against Wagnerian innovations. They were supported by the conservative leanings of some German music schools, including the

conservatories at

Leipzig under

Ignaz Moscheles and at

Cologne under the direction of Ferdinand Hiller. Another Wagner detractor was the French composer

Charles-Valentin Alkan, who wrote to Hiller after attending Wagner's Paris concert on 25 January 1860 at which Wagner conducted the overtures to

Der fliegende Holländer and

Tannhäuser, the preludes to

Lohengrin and

Tristan und Isolde, and six other extracts from

Tannhäuser and

Lohengrin:

"I had imagined that I was going to meet music of an innovative kind

but was astonished to find a pale imitation of Berlioz ... I do not like

all the music of Berlioz while appreciating his marvellous

understanding of certain instrumental effects ... but here he was

imitated and caricatured ... Wagner is not a musician, he is a disease."

Even those who, like Debussy, opposed Wagner ("this old poisoner")

could not deny his influence. Indeed, Debussy was one of many

composers, including Tchaikovsky, who felt the need to break with Wagner

precisely because his influence was so unmistakable and overwhelming.

"Golliwogg's Cakewalk" from Debussy's

Children's Corner piano suite contains a deliberately tongue-in-cheek quotation from the opening bars of

Tristan. Others who proved resistant to Wagner's operas included

Gioachino Rossini, who said "Wagner has wonderful moments, and dreadful quarters of an hour." In the 20th century Wagner's music was parodied by

Paul Hindemith and

Hanns Eisler, among others.

Wagner's followers (known as Wagnerians or Wagnerites) have formed many societies dedicated to Wagner's life and work.

Film and stage portrayals

Bayreuth Festival

Since Wagner's death, the Bayreuth Festival, which has become an

annual event, has been successively directed by his widow, his son

Siegfried, the latter's widow

Winifred Wagner, their two sons

Wieland and

Wolfgang Wagner, and, presently, two of the composer's great-granddaughters,

Eva Wagner-Pasquier and

Katharina Wagner. Since 1973, the festival has been overseen by the

Richard-Wagner-Stiftung (Richard Wagner Foundation), the members of which include a number of Wagner's descendants.

Controversies

Wagner's operas, writings, politics, beliefs and unorthodox lifestyle made him a controversial figure during his lifetime.

Following his death, debate about his ideas and their interpretation,

particularly in Germany during the 20th century, has continued.

Racism and antisemitism

Caricature of Wagner by Karl Clic in the Viennese satirical magazine, Humoristische Blätter (1873). The exaggerated features refer to rumours of Wagner's Jewish ancestry.

Wagner's hostile writings on Jews, including

Jewishness in Music, corresponded to some existing trends of thought in Germany during the 19th century;

however, despite his very public views on these themes, throughout his

life Wagner had Jewish friends, colleagues and supporters. There have been frequent suggestions that

antisemitic stereotypes are represented in Wagner's operas. The characters of

Alberich and Mime in the

Ring, Sixtus Beckmesser in

Die Meistersinger, and Klingsor in

Parsifal are sometimes claimed as Jewish representations, though they are not identified as such in the librettos of these operas.

The topic of Wagner and the Jews is further complicated by allegations,

which may have been credited by Wagner, that he himself was of Jewish

ancestry, via his supposed father Geyer.

Some biographers have noted that Wagner in his final years developed interest in the

racialist philosophy of

Arthur de Gobineau, notably Gobineau's belief that Western society was doomed because of

miscegenation between "superior" and "inferior" races. According to Robert Gutman, this theme is reflected in the opera

Parsifal.

Other biographers (such as Lucy Beckett) believe that this is not true,

as the original drafts of the story date back to 1857 and Wagner had

completed the libretto for

Parsifal by 1877; but he displayed no significant interest in Gobineau until 1880.

Other interpretations

Wagner's

ideas are amenable to socialist interpretations; many of his ideas on

art were being formulated at the time of his revolutionary inclinations

in the 1840s. Thus, for example,

George Bernard Shaw wrote in

The Perfect Wagnerite (1883):

Left-wing interpretations of Wagner also inform the writings of

Theodor Adorno among other Wagner critics.

Walter Benjamin gave Wagner as an example of "bourgeois false consciousness", alienating art from its social context.

The writer

Robert Donington has produced a detailed, if controversial,

Jungian interpretation of the

Ring

cycle, described as "an approach to Wagner by way of his symbols",

which, for example, sees the character of the goddess Fricka as part of

her husband Wotan's "inner femininity". Millington notes that

Jean-Jacques Nattiez has also applied

psychoanalytical techniques in an evaluation of Wagner's life and works.

Nazi appropriation

Adolf Hitler

was an admirer of Wagner's music and saw in his operas an embodiment of

his own vision of the German nation; in a 1922 speech he claimed that

Wagner's works glorified "the heroic Teutonic nature ... Greatness lies

in the heroic." Hitler visited Bayreuth frequently from 1923 onwards and attended the productions at the theatre. There continues to be debate about the extent to which Wagner's views might have influenced

Nazi thinking.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), who married Wagner's daughter Eva in 1908 but never met Wagner, was the author of the racist book

The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, approved by the Nazi movement. Chamberlain met Hitler on a number of occasions between 1923 and 1927

in Bayreuth, but cannot credibly be regarded as a conduit of Wagner's

own views. The Nazis used those parts of Wagner's thought that were useful for propaganda and ignored or suppressed the rest.

While Bayreuth presented a useful front for Nazi culture, and Wagner's music was used at many Nazi events,

the Nazi hierarchy as a whole did not share Hitler's enthusiasm for

Wagner's operas and resented attending these lengthy epics at Hitler's

insistence.

Guido Fackler has researched evidence that indicates that it is possible that Wagner's music was used at the

Dachau concentration camp in 1933–34 to "reeducate"

political prisoners by exposure to "national music". There has been no evidence to support claims, sometimes made, that his music was played at

Nazi death camps during the

Second World War, and Pamela Potter has noted that Wagner's music was explicitly off-limits in the camps.

![{\displaystyle C_{0}^{N}=\mathrm {tr} [(\bigotimes _{j=1}^{N}\rho _{j}){[S_{N}-K]}^{+}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4bb1209096d530c0e91e2c9dd4a71726decc4cb3)

![{\displaystyle C_{0}^{N}=(1+r)^{-N}\sum _{n=0}^{N}{\frac {N!}{n!(N-n)!}}q^{n}{(1-q)}^{N-n}{[S_{0}{(1+b)}^{n}{(1+a)}^{N-n}-K]}^{+}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a04ca38e1c912cfa163e5b79ffc9dabd1f3a5151)

![{\displaystyle C_{0}^{N}=(1+r)^{-N}\sum _{n=0}^{N}\left({\frac {q^{n}{(1-q)}^{N-n}}{\sum _{k=0}^{N}q^{k}{(1-q)}^{N-k}}}\right){[S_{0}{(1+b)}^{n}{(1+a)}^{N-n}-K]}^{+}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c53ef29dcea57a138fe5af6efbee5a05acb32dc)