From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Lobotomy |

|---|

"Dr.

Walter Freeman, left, and Dr. James W. Watts study an X ray before a

psychosurgical operation. Psychosurgery is cutting into the brain to

form new patterns and rid a patient of delusions, obsessions, nervous

tensions and the like." Waldemar Kaempffert, "Turning the Mind Inside

Out", Saturday Evening Post, 24 May 1941. |

| Other names | Leukotomy, leucotomy |

|---|

| ICD-9-CM | 01.32 |

|---|

| MeSH | D011612 |

|---|

A lobotomy, or leucotomy, is a form of psychosurgery, a neurosurgical treatment of a mental disorder that involves severing connections in the brain's prefrontal cortex.[2] Most of the connections to and from the prefrontal cortex, the anterior part of the frontal lobes of the brain, are severed. It was used for treating mental disorders

and occasionally other conditions as a mainstream procedure in some

Western countries for more than two decades, despite general recognition

of frequent and serious side effects. Some patients improved in some

ways after the operation, but complications and impairments – sometimes

severe – were frequent. The procedure was controversial from its initial

use, in part due to the balance between benefits and risks. Today, the

lobotomy has become a disparaged procedure, a byword for medical

barbarism and an exemplary instance of the medical trampling of patients' rights.

The originator of the procedure, Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz, shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine of 1949 for the "discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy in certain psychoses", although the awarding of the prize has been subject to controversy.

The use of the procedure increased dramatically from the early

1940s and into the 1950s; by 1951, almost 20,000 lobotomies had been

performed in the United States and proportionally more in the United

Kingdom.

The majority of lobotomies were performed on women; a 1951 study of

American hospitals found nearly 60% of lobotomy patients were women;

limited data shows 74% of lobotomies in Ontario from 1948–1952 were performed on women. From the 1950s onward, lobotomy began to be abandoned, first in the Soviet Union and Europe. The term is derived from Greek: λοβός lobos "lobe" and τομή tomē "cut, slice".

Effects

I fully realize that

this operation will have little effect on her mental condition but am

willing to have it done in the hope that she will be more comfortable

and easier to care for.

— `Comments added to the consent

form for a lobotomy operation on "Helaine Strauss", the pseudonym used

for "a patient at an elite private hospital".

Historically, patients of lobotomy were, immediately following surgery, often stuporous, confused, and incontinent. Some developed an enormous appetite and gained considerable weight. Seizures

were another common complication of surgery. Emphasis was put on the

training of patients in the weeks and months following surgery.

The purpose of the operation was to reduce the symptoms of mental disorders,

and it was recognized that this was accomplished at the expense of a

person's personality and intellect. British psychiatrist Maurice

Partridge, who conducted a follow-up study of 300 patients, said that

the treatment achieved its effects by "reducing the complexity of

psychic life". Following the operation, spontaneity, responsiveness,

self-awareness, and self-control were reduced. The activity was replaced

by inertia, and people were left emotionally blunted and restricted in their intellectual range.

The consequences of the operation have been described as "mixed".

Some patients died as a result of the operation and others later

committed suicide. Some were left severely brain damaged. Others were

able to leave the hospital, or became more manageable within the

hospital.

A few people managed to return to responsible work, while at the other

extreme, people were left with severe and disabling impairments.

Most people fell into an intermediate group, left with some improvement

of their symptoms but also with emotional and intellectual deficits to

which they made a better or worse adjustment. On average, there was a mortality rate of approximately 5% during the 1940s.

The lobotomy procedure could have severe negative effects on a patient's personality and ability to function independently. Lobotomy patients often show a marked reduction in initiative and inhibition.

They may also exhibit difficulty putting themselves in the position of

others because of decreased cognition and detachment from society.

Walter Freeman

coined the term "surgically induced childhood" and used it constantly

to refer to the results of lobotomy. The operation left people with an

"infantile personality"; a period of maturation would then, according to

Freeman, lead to recovery. In an unpublished memoir, he described how

the "personality of the patient was changed in some way in the hope of

rendering him more amenable to the social pressures under which he is

supposed to exist." He described one 29-year-old woman as being,

following lobotomy, a "smiling, lazy and satisfactory patient with the

personality of an oyster" who could not remember Freeman's name and

endlessly poured coffee from an empty pot. When her parents had

difficulty dealing with her behavior, Freeman advised a system of

rewards (ice cream) and punishment (smacks).

History

In the early 20th century, the number of patients residing in mental hospitals increased significantly while little in the way of effective medical treatment was available.

Lobotomy was one of a series of radical and invasive physical therapies

developed in Europe at this time that signaled a break with a

psychiatric culture of therapeutic nihilism that had prevailed since the late nineteenth-century. The new "heroic" physical therapies devised during this experimental era, including malarial therapy for general paresis of the insane (1917), deep sleep therapy (1920), insulin shock therapy (1933), cardiazol shock therapy (1934), and electroconvulsive therapy (1938),

helped to imbue the then therapeutically moribund and demoralised

psychiatric profession with a renewed sense of optimism in the

curability of insanity and the potency of their craft.

The success of the shock therapies, despite the considerable risk they

posed to patients, also helped to accommodate psychiatrists to ever more

drastic forms of medical intervention, including lobotomy.

The clinician-historian Joel Braslow argues that from malarial

therapy onward to lobotomy, physical psychiatric therapies "spiral

closer and closer to the interior of the brain" with this organ

increasingly taking "center stage as a source of disease and site of

cure". For Roy Porter, once the doyen of medical history,

the often violent and invasive psychiatric interventions developed

during the 1930s and 1940s are indicative of both the well-intentioned

desire of psychiatrists to find some medical means of alleviating the

suffering of the vast number of patients then in psychiatric hospitals

and also the relative lack of social power of those same patients to

resist the increasingly radical and even reckless interventions of

asylum doctors.

Many doctors, patients and family members of the period believed that

despite potentially catastrophic consequences, the results of lobotomy

were seemingly positive in many instances or, at least they were deemed

as such when measured next to the apparent alternative of long-term

institutionalisation. Lobotomy has always been controversial, but for a

period of the medical mainstream, it was even feted and regarded as a

legitimate last resort remedy for categories of patients who were

otherwise regarded as hopeless.

Today, lobotomy has become a disparaged procedure, a byword for medical

barbarism and an exemplary instance of the medical trampling of patients' rights.

Early psychosurgery

Gottlieb Burckhardt (1836–1907)

Before the 1930s, individual doctors had infrequently experimented

with novel surgical operations on the brains of those deemed insane.

Most notably in 1888, the Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt initiated what is commonly considered the first systematic attempt at modern human psychosurgery. He operated on six chronic patients under his care at the Swiss Préfargier Asylum, removing sections of their cerebral cortex.

Burckhardt's decision to operate was informed by three pervasive views

on the nature of mental illness and its relationship to the brain.

First, the belief that mental illness was organic in nature, and

reflected an underlying brain pathology; next, that the nervous system

was organized according to an associationist model comprising an input or afferent system (a sensory center), a connecting system where information processing took place (an association center), and an output or efferent

system (a motor center); and, finally, a modular conception of the

brain whereby discrete mental faculties were connected to specific

regions of the brain. Burckhardt's hypothesis was that by deliberately creating lesions in regions of the brain identified as association centers a transformation in behavior might ensue.

According to his model, those mentally ill might experience

"excitations abnormal in quality, quantity and intensity" in the sensory

regions of the brain and this abnormal stimulation would then be

transmitted to the motor regions giving rise to mental pathology.

He reasoned, however, that removing material from either of the sensory

or motor zones could give rise to "grave functional disturbance". Instead, by targeting the association centers and creating a "ditch" around the motor region of the temporal lobe, he hoped to break their lines of communication and thus alleviate both mental symptoms and the experience of mental distress.

Intending to ameliorate symptoms in those with violent and intractable conditions rather than effect a cure, Burckhardt began operating on patients in December 1888, but both his surgical methods and instruments were crude and the results of the procedure were mixed at best.

He operated on six patients in total and, according to his own

assessment, two experienced no change, two patients became quieter, one

patient experienced epileptic convulsions and died a few days after the operation, and one patient improved. Complications included motor weakness, epilepsy, sensory aphasia and "word deafness". Claiming a success rate of 50 percent,

he presented the results at the Berlin Medical Congress and published a

report, but the response from his medical peers was hostile and he did

no further operations.

In 1912, two physicians based in Saint Petersburg, the leading Russian neurologist Vladimir Bekhterev and his younger Estonian colleague, the neurosurgeon Ludvig Puusepp, published a paper reviewing a range of surgical interventions that had been performed on the mentally ill.

While generally treating these endeavours favorably, in their

consideration of psychosurgery they reserved unremitting scorn for

Burckhardt's surgical experiments of 1888 and opined that it was

extraordinary that a trained medical doctor could undertake such an

unsound procedure.

We have quoted this data to show

not only how groundless but also how dangerous these operations were. We

are unable to explain how their author, holder of a degree in medicine,

could bring himself to carry them out ...

The authors neglected to mention, however, that in 1910 Puusepp

himself had performed surgery on the brains of three mentally ill

patients, sectioning the cortex between the frontal and parietal lobes.

He had abandoned these attempts because of unsatisfactory results and

this experience probably inspired the invective that was directed at

Burckhardt in the 1912 article.

By 1937, Puusepp, despite his earlier criticism of Burckhardt, was

increasingly persuaded that psychosurgery could be a valid medical

intervention for the mentally disturbed. In the late 1930s, he worked closely with the neurosurgical team of the Racconigi Hospital near Turin to establish it as an early and influential centre for the adoption of leucotomy in Italy.

Development

Leucotomy was first undertaken in 1935 under the direction of the Portuguese neurologist (and inventor of the term psychosurgery) António Egas Moniz.First developing an interest in psychiatric conditions and their somatic treatment in the early 1930s,

Moniz apparently conceived a new opportunity for recognition in the

development of a surgical intervention on the brain as a treatment for

mental illness.

Frontal lobes

The

source of inspiration for Moniz's decision to hazard psychosurgery has

been clouded by contradictory statements made on the subject by Moniz

and others both contemporaneously and retrospectively.

The traditional narrative addresses the question of why Moniz targeted

the frontal lobes by way of reference to the work of the Yale

neuroscientist John Fulton and, most dramatically, to a presentation Fulton made with his junior colleague Carlyle Jacobsen at the Second International Congress of Neurology held in London in 1935.

Fulton's primary area of research was on the cortical function of

primates and he had established America's first primate neurophysiology

laboratory at Yale in the early 1930s. At the 1935 Congress, with Moniz in attendance, Fulton and Jacobsen presented two chimpanzees, named Becky and Lucy who had had frontal lobectomies and subsequent changes in behaviour and intellectual function.

According to Fulton's account of the congress, they explained that

before surgery, both animals, and especially Becky, the more emotional

of the two, exhibited "frustrational behaviour" – that is, have tantrums

that could include rolling on the floor and defecating – if, because of

their poor performance in a set of experimental tasks, they were not

rewarded.

Following the surgical removal of their frontal lobes, the behaviour of

both primates changed markedly and Becky was pacified to such a degree

that Jacobsen apparently stated it was as if she had joined a "happiness

cult".

During the question and answer section of the paper, Moniz, it is

alleged, "startled" Fulton by inquiring if this procedure might be

extended to human subjects suffering from mental illness. Fulton stated

that he replied that while possible in theory it was surely "too

formidable" an intervention for use on humans.

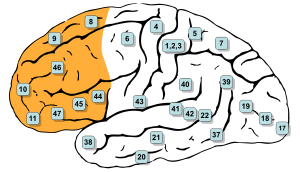

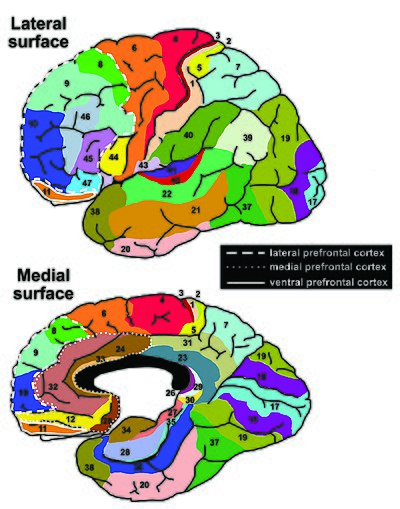

Brain animation: left

frontal lobe highlighted in red. Moniz targeted the frontal lobes in the leucotomy procedure he first conceived in 1933.

That Moniz began his experiments with leucotomy just three months

after the congress has reinforced the apparent cause and effect

relationship between the Fulton and Jacobsen presentation and the

Portuguese neurologist's resolve to operate on the frontal lobes.

As the author of this account Fulton, who has sometimes been claimed as

the father of lobotomy, was later able to record that the technique had

its true origination in his laboratory. Endorsing this version of events, in 1949, the Harvard neurologist Stanley Cobb remarked during his presidential address to the American Neurological Association

that "seldom in the history of medicine has a laboratory observation

been so quickly and dramatically translated into a therapeutic

procedure". Fulton's report, penned ten years after the events

described, is, however, without corroboration in the historical record

and bears little resemblance to an earlier unpublished account he wrote

of the congress. In this previous narrative he mentioned an incidental,

private exchange with Moniz, but it is likely that the official version

of their public conversation he promulgated is without foundation.

In fact, Moniz stated that he had conceived of the operation some time

before his journey to London in 1935, having told in confidence his

junior colleague, the young neurosurgeon Pedro Almeida Lima, as early as 1933 of his psychosurgical idea.

The traditional account exaggerates the importance of Fulton and

Jacobsen to Moniz's decision to initiate frontal lobe surgery, and omits

the fact that a detailed body of neurological research that emerged at

this time suggested to Moniz and other neurologists and neurosurgeons

that surgery on this part of the brain might yield significant

personality changes in the mentally ill.

As the frontal lobes had been the object of scientific inquiry

and speculation since the late 19th century, Fulton's contribution,

while it may have functioned as source of intellectual support, is of

itself unnecessary and inadequate as an explanation of Moniz's

resolution to operate on this section of the brain.

Under an evolutionary and hierarchical model of brain development it

had been hypothesized that those regions associated with more recent

development, such as the mammalian brain and, most especially, the frontal lobes, were responsible for more complex cognitive functions.

However, this theoretical formulation found little laboratory support,

as 19th-century experimentation found no significant change in animal

behaviour following surgical removal or electrical stimulation of the

frontal lobes.

This picture of the so-called "silent lobe" changed in the period after

World War I with the production of clinical reports of ex-servicemen

who had suffered brain trauma. The refinement of neurosurgical

techniques also facilitated increasing attempts to remove brain tumours,

treat focal epilepsy in humans and led to more precise experimental neurosurgery in animal studies. Cases were reported where mental symptoms were alleviated following the surgical removal of diseased or damaged brain tissue.

The accumulation of medical case studies on behavioural changes

following damage to the frontal lobes led to the formulation of the

concept of Witzelsucht, which designated a neurological condition characterised by a certain hilarity and childishness in the afflicted.

The picture of frontal lobe function that emerged from these studies

was complicated by the observation that neurological deficits attendant

on damage to a single lobe might be compensated for if the opposite lobe

remained intact. In 1922, the Italian neurologist Leonardo Bianchi

published a detailed report on the results of bilateral lobectomies in

animals that supported the contention that the frontal lobes were both

integral to intellectual function and that their removal led to the

disintegration of the subject's personality. This work, while influential, was not without its critics due to deficiencies in experimental design.

The first bilateral lobectomy of a human subject was performed by the American neurosurgeon Walter Dandy in 1930. The neurologist Richard Brickner reported on this case in 1932, relating that the recipient, known as "Patient A", while experiencing a blunting of affect, had suffered no apparent decrease in intellectual function and seemed, at least to the casual observer, perfectly normal. Brickner concluded from this evidence that "the frontal lobes are not 'centers' for the intellect". These clinical results were replicated in a similar operation undertaken in 1934 by the neurosurgeon Roy Glenwood Spurling and reported on by the neuropsychiatrist Spafford Ackerly.

By the mid-1930s, interest in the function of the frontal lobes reached

a high-water mark. This was reflected in the 1935 neurological congress

in London, which hosted as part of its deliberations, "a remarkable symposium ... on the functions of the frontal lobes". The panel was chaired by Henri Claude,

a French neuropsychiatrist, who commenced the session by reviewing the

state of research on the frontal lobes, and concluded that "altering the

frontal lobes profoundly modifies the personality of subjects".

This parallel symposium contained numerous papers by neurologists,

neurosurgeons and psychologists; amongst these was one by Brickner,

which impressed Moniz greatly, that again detailed the case of "Patient A".

Fulton and Jacobsen's paper, presented in another session of the

conference on experimental physiology, was notable in linking animal and

human studies on the function of the frontal lobes.

Thus, at the time of the 1935 Congress, Moniz had available to him an

increasing body of research on the role of the frontal lobes that

extended well beyond the observations of Fulton and Jacobsen.

Nor was Moniz the only medical practitioner in the 1930s to have contemplated procedures directly targeting the frontal lobes. Although ultimately discounting brain surgery as carrying too much risk, physicians and neurologists such as William Mayo, Thierry de Martel, Richard Brickner, and Leo Davidoff had, before 1935, entertained the proposition. Inspired by Julius Wagner-Jauregg's development of malarial therapy for the treatment of general paresis of the insane,

the French physician Maurice Ducosté reported in 1932 that he had

injected 5 ml of malarial blood directly into the frontal lobes of over

100 paretic patients through holes drilled into the skull.

He claimed that the injected paretics showed signs of "uncontestable

mental and physical amelioration" and that the results for psychotic

patients undergoing the procedure was also "encouraging".

The experimental injection of fever-inducing malarial blood into the

frontal lobes was also replicated during the 1930s in the work of Ettore

Mariotti and M. Sciutti in Italy and Ferdière Coulloudon in France.

In Switzerland, almost simultaneously with the commencement of Moniz's

leucotomy programme, the neurosurgeon François Ody had removed the

entire right frontal lobe of a catatonic schizophrenic patient.

In Romania, Ody's procedure was adopted by Dimitri Bagdasar and

Constantinesco working out of the Central Hospital in Bucharest.

Ody, who delayed publishing his own results for several years, later

rebuked Moniz for claiming to have cured patients through leucotomy

without waiting to determine if there had been a "lasting remission".

Neurological model

The

theoretical underpinnings of Moniz's psychosurgery were largely

commensurate with the nineteenth-century ones that had informed

Burckhardt's decision to excise matter from the brains of his patients.

Although in his later writings Moniz referenced both the neuron theory of Ramón y Cajal and the conditioned reflex of Ivan Pavlov, in essence he simply interpreted this new neurological research in terms of the old psychological theory of associationism.

He differed significantly from Burckhardt, however in that he did not

think there was any organic pathology in the brains of the mentally ill,

but rather that their neural pathways were caught in fixed and

destructive circuits leading to "predominant, obsessive ideas". As Moniz wrote in 1936:

[The] mental troubles must have ... a relation with the

formation of cellulo-connective groupings, which become more or less

fixed. The cellular bodies may remain altogether normal, their cylinders

will not have any anatomical alterations; but their multiple liaisons,

very variable in normal people, may have arrangements more or less

fixed, which will have a relation with persistent ideas and deliria in

certain morbid psychic states.

For Moniz, "to cure these patients," it was necessary to "destroy the

more or less fixed arrangements of cellular connections that exist in

the brain, and particularly those which are related to the frontal

lobes", thus removing their fixed pathological brain circuits. Moniz believed the brain would functionally adapt to such injury. Unlike the position adopted by Burckhardt, it was unfalsifiable

according to the knowledge and technology of the time as the absence of

a known correlation between physical brain pathology and mental illness

could not disprove his thesis.

First leucotomies

The hypotheses

underlying the procedure might be called into question; the surgical

intervention might be considered very audacious; but such arguments

occupy a secondary position because it can be affirmed now that these

operations are not prejudicial to either physical or psychic life of the

patient, and also that recovery or improvement may be obtained

frequently in this way

Egas Moniz (1937)

On 12 November 1935 at the Hospital Santa Marta in Lisbon, Moniz initiated the first of a series of operations on the brains of the mentally ill.

The initial patients selected for the operation were provided by the

medical director of Lisbon's Miguel Bombarda Mental Hospital, José de

Matos Sobral Cid.

As Moniz lacked training in neurosurgery and his hands were crippled

from gout, the procedure was performed under general anaesthetic by

Pedro Almeida Lima, who had previously assisted Moniz with his research

on cerebral angiography. The intention was to remove some of the long fibres that connected the frontal lobes to other major brain centres. To this end, it was decided that Lima would trephine into the side of the skull and then inject ethanol into the "subcortical white matter of the prefrontal area" so as to destroy the connecting fibres, or association tracts, and create what Moniz termed a "frontal barrier".

After the first operation was complete, Moniz considered it a success

and, observing that the patient's depression had been relieved, he

declared her "cured" although she was never, in fact, discharged from

the mental hospital.

Moniz and Lima persisted with this method of injecting alcohol into the

frontal lobes for the next seven patients but, after having to inject

some patients on numerous occasions to elicit what they considered a

favourable result, they modified the means by which they would section

the frontal lobes. For the ninth patient they introduced a surgical instrument called a leucotome; this was a cannula

that was 11 centimetres (4.3 in) in length and 2 centimetres (0.79 in)

in diameter. It had a retractable wire loop at one end that, when

rotated, produced a 1 centimetre (0.39 in) diameter circular lesion in

the white matter of the frontal lobe.

Typically, six lesions were cut into each lobe, but, if they were

dissatisfied by the results, Lima might perform several procedures, each

producing multiple lesions in the left and right frontal lobes.

By the conclusion of this first run of leucotomies in February

1936, Moniz and Lima had operated on twenty patients with an average

period of one week between each procedure; Moniz published his findings

with great haste in March of the same year.

The patients were aged between 27 and 62 years of age; twelve were

female and eight were male. Nine of the patients were diagnosed as

suffering from depression, six from schizophrenia, two from panic disorder, and one each from mania, catatonia and manic-depression

with the most prominent symptoms being anxiety and agitation. The

duration of the illness before the procedure varied from as little as

four weeks to as much as 22 years, although all but four had been ill

for at least one year.

Patients were normally operated on the day they arrived at Moniz's

clinic and returned within ten days to the Miguel Bombarda Mental

Hospital. A perfunctory post-operative follow-up assessment took place anywhere from one to ten weeks following surgery. Complications were observed in each of the leucotomy patients and included: "increased temperature, vomiting, bladder and bowel incontinence, diarrhea, and ocular affections such as ptosis and nystagmus, as well as psychological effects such as apathy, akinesia, lethargy, timing and local disorientation, kleptomania, and abnormal sensations of hunger". Moniz asserted that these effects were transitory and,

according to his published assessment, the outcome for these first

twenty patients was that 35%, or seven cases, improved significantly,

another 35% were somewhat improved and the remaining 30% (six cases)

were unchanged. There were no deaths and he did not consider that any

patients had deteriorated following leucotomy.

Reception

Moniz rapidly disseminated his results through articles in the medical press and a monograph in 1936. Initially, however, the medical community appeared hostile to the new procedure.

On 26 July 1936, one of his assistants, Diogo Furtado, gave a

presentation at the Parisian meeting of the Société Médico-Psychologique

on the results of the second cohort of patients leucotomised by Lima.

Sobral Cid, who had supplied Moniz with the first set of patients for

leucotomy from his own hospital in Lisbon, attended the meeting and

denounced the technique,

declaring that the patients who had been returned to his care

post-operatively were "diminished" and had suffered a "degradation of

personality".

He also claimed that the changes Moniz observed in patients were more

properly attributed to shock and brain trauma, and he derided the

theoretical architecture that Moniz had constructed to support the new

procedure as "cerebral mythology."

At the same meeting the Parisian psychiatrist, Paul Courbon, stated he

could not endorse a surgical technique that was solely supported by

theoretical considerations rather than clinical observations.

He also opined that the mutilation of an organ could not improve its

function and that such cerebral wounds as were occasioned by leucotomy

risked the later development of meningitis, epilepsy and brain abscesses.

Nonetheless, Moniz's reported successful surgical treatment of 14 out

of 20 patients led to the rapid adoption of the procedure on an

experimental basis by individual clinicians in countries such as Brazil,

Cuba, Italy, Romania and the United States during the 1930s.

Italian leucotomy

In the present state

of affairs if some are critical about lack of caution in therapy, it is,

on the other hand, deplorable and inexcusable to remain apathetic, with

folded hands, content with learned lucubrations upon symptomatologic

minutiae or upon psychopathic curiosities, or even worse, not even doing

that.

Amarro Fiamberti

Throughout the remainder of the 1930s the number of leucotomies

performed in most countries where the technique was adopted remained

quite low. In Britain, which was later a major centre for leucotomy, only six operations had been undertaken before 1942.

Generally, medical practitioners who attempted the procedure adopted a

cautious approach and few patients were leucotomised before the 1940s.

Italian neuropsychiatrists, who were typically early and enthusiastic

adopters of leucotomy, were exceptional in eschewing such a gradualist

course.

Leucotomy was first reported in the Italian medical press in 1936

and Moniz published an article in Italian on the technique in the

following year.

In 1937, he was invited to Italy to demonstrate the procedure and for a

two-week period in June of that year he visited medical centres in Trieste, Ferrara, and one close to Turin

– the Racconigi Hospital – where he instructed his Italian

neuropsychiatric colleagues on leucotomy and also oversaw several

operations.

Leucotomy was featured at two Italian psychiatric conferences in 1937

and over the next two years a score of medical articles on Moniz's

psychosurgery was published by Italian clinicians based in medical

institutions located in Racconigi, Trieste, Naples, Genoa, Milan, Pisa, Catania and Rovigo. The major centre for leucotomy in Italy was the Racconigi Hospital, where the experienced neurosurgeon Ludvig Puusepp provided a guiding hand.

Under the medical directorship of Emilio Rizzatti, the medical

personnel at this hospital had completed at least 200 leucotomies by

1939. Reports from clinicians based at other Italian institutions detailed significantly smaller numbers of leucotomy operations.

Experimental modifications of Moniz's operation were introduced with little delay by Italian medical practitioners. Most notably, in 1937 Amarro Fiamberti, the medical director of a psychiatric institution in Varese, first devised the transorbital procedure whereby the frontal lobes were accessed through the eye sockets. Fiamberti's method was to puncture the thin layer of orbital

bone at the top of the socket and then inject alcohol or formalin into

the white matter of the frontal lobes through this aperture. Using this method, while sometimes substituting a leucotome

for a hypodermic needle, it is estimated that he leucotomised about 100

patients in the period up to the outbreak of World War II. Fiamberti's innovation of Moniz's method would later prove inspirational for Walter Freeman's development of transorbital lobotomy.

American leucotomy

Site of borehole for the standard pre-frontal lobotomy/leucotomy operation as developed by Freeman and Watts

The first prefrontal leucotomy in the United States was performed at

the George Washington University Hospital on 14 September 1936 by the neurologist Walter Freeman and his friend and colleague, the neurosurgeon, James W. Watts.

Freeman had first encountered Moniz at the London-hosted Second

International Congress of Neurology in 1935 where he had presented a

poster exhibit of the Portuguese neurologist's work on cerebral

angiography.

Fortuitously occupying a booth next to Moniz, Freeman, delighted by

their chance meeting, formed a highly favourable impression of Moniz,

later remarking upon his "sheer genius".

According to Freeman, if they had not met in person it is highly

unlikely that he would have ventured into the domain of frontal lobe

psychosurgery.

Freeman's interest in psychiatry was the natural outgrowth of his

appointment in 1924 as the medical director of the Research Laboratories

of the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, known

colloquially as St Elizabeth's.

Ambitious and a prodigious researcher, Freeman, who favoured an organic

model of mental illness causation, spent the next several years

exhaustively, yet ultimately fruitlessly, investigating a neuropathological basis for insanity.

Chancing upon a preliminary communication by Moniz on leucotomy in the

spring of 1936, Freeman initiated a correspondence in May of that year.

Writing that he had been considering psychiatric brain surgery

previously, he informed Moniz that, "having your authority I expect to

go ahead".

Moniz, in return, promised to send him a copy of his forthcoming

monograph on leucotomy and urged him to purchase a leucotome from a

French supplier.

Upon receipt of Moniz's monograph, Freeman reviewed it anonymously for the Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. Praising the text as one whose "importance can scarcely be overestimated",

he summarised Moniz's rationale for the procedure as based on the fact

that while no physical abnormality of cerebral cell bodies was

observable in the mentally ill, their cellular interconnections may

harbour a "fixation of certain patterns of relationship among various

groups of cells" and that this resulted in obsessions, delusions and

mental morbidity.

While recognising that Moniz's thesis was inadequate, for Freeman it

had the advantage of circumventing the search for diseased brain tissue

in the mentally ill by instead suggesting that the problem was a

functional one of the brain's internal wiring where relief might be

obtained by severing problematic mental circuits.

In 1937 Freeman and Watts adapted Lima and Moniz's surgical procedure, and created the Freeman-Watts technique, also known as the Freeman-Watts standard prefrontal lobotomy, which they styled the "precision method".

Transorbital lobotomy

The

Freeman-Watts prefrontal lobotomy still required drilling holes in the

skull, so surgery had to be performed in an operating room by trained

neurosurgeons. Walter Freeman believed this surgery would be unavailable

to those he saw as needing it most: patients in state mental hospitals

that had no operating rooms, surgeons, or anesthesia and limited budgets. Freeman wanted to simplify the procedure so that it could be carried out by psychiatrists in psychiatric hospitals.

Inspired by the work of Italian psychiatrist Amarro Fiamberti,

Freeman at some point conceived of approaching the frontal lobes

through the eye sockets instead of through drilled holes in the skull.

In 1945 he took an icepick from his own kitchen and began testing the idea on grapefruit and cadavers.

This new "transorbital" lobotomy involved lifting the upper eyelid and

placing the point of a thin surgical instrument (often called an orbitoclast

or leucotome, although quite different from the wire loop leucotome

described above) under the eyelid and against the top of the eyesocket. A

mallet was used to drive the orbitoclast through the thin layer of bone

and into the brain along the plane of the bridge of the nose, around 15

degrees toward the interhemispherical fissure. The orbitoclast was

malleted 5 centimeters (2 in) into the frontal lobe, and then pivoted 40

degrees at the orbit perforation so the tip cut toward the opposite

side of the head (toward the nose). The instrument was returned to the

neutral position and sent a further 2 centimeters (4⁄5 in)

into the brain, before being pivoted around 28 degrees each side, to

cut outwards and again inwards. (In a more radical variation at the end

of the last cut described, the butt of the orbitoclast was forced

upwards so the tool cut vertically down the side of the cortex of the interhemispheric fissure;

the "Deep Frontal Cut".) All cuts were designed to transect the white

fibrous matter connecting the cortical tissue of the prefrontal cortex

to the thalamus. The leucotome was then withdrawn and the procedure repeated on the other side.

Freeman performed the first transorbital lobotomy on a live

patient in 1946. Its simplicity suggested the possibility of carrying it

out in mental hospitals lacking the surgical facilities required for

the earlier, more complex procedure. (Freeman suggested that, where

conventional anesthesia was unavailable, electroconvulsive therapy be used to render the patient unconscious.)

In 1947, the Freeman and Watts partnership ended, as the latter was

disgusted by Freeman's modification of the lobotomy from a surgical

operation into a simple "office" procedure.

Between 1940 and 1944, 684 lobotomies were performed in the United

States. However, because of the fervent promotion of the technique by

Freeman and Watts, those numbers increased sharply towards the end of

the decade. In 1949, the peak year for lobotomies in the US, 5,074

procedures were undertaken, and by 1951 over 18,608 individuals had been

lobotomized in the US.

Prevalence

In

the United States, approximately 40,000 people were lobotomized. In

England, 17,000 lobotomies were performed, and the three Nordic

countries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden had a combined figure of

approximately 9,300 lobotomies. Scandinavian hospitals lobotomized 2.5 times as many people per capita as hospitals in the US. Sweden lobotomized at least 4,500 people between 1944 and 1966, mainly women. This figure includes young children. In Norway, there were 2,005 known lobotomies. In Denmark, there were 4,500 known lobotomies.

In Japan, the majority of lobotomies were performed on children with

behavior problems. The Soviet Union banned the practice in 1950 on moral

grounds. In Germany, it was performed only a few times. By the late 1970s, the practice of lobotomy had generally ceased, although it continued as late as the 1980s in France.

Criticism

As early as 1944 an author in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease

remarked: "The history of prefrontal lobotomy has been brief and

stormy. Its course has been dotted with both violent opposition and with

slavish, unquestioning acceptance." Beginning in 1947 Swedish

psychiatrist Snorre Wohlfahrt evaluated early trials, reporting that it

is "distinctly hazardous to leucotomize schizophrenics" and that

lobotomy was "still too imperfect to enable us, with its aid, to venture

on a general offensive against chronic cases of mental disorder",

stating further that "Psychosurgery has as yet failed to discover its

precise indications and contraindications and the methods must

unfortunately still be regarded as rather crude and hazardous in many

respects." In 1948 Norbert Wiener, the author of Cybernetics: Or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine,

said: "[P]refrontal lobotomy ... has recently been having a certain

vogue, probably not unconnected with the fact that it makes the

custodial care of many patients easier. Let me remark in passing that

killing them makes their custodial care still easier."

Concerns about lobotomy steadily grew. Soviet psychiatrist Vasily

Gilyarovsky criticized lobotomy and the mechanistic brain localization

assumption used to carry out lobotomy:

It is assumed that the transection

of white substance of the frontal lobes impairs their connection with

the thalamus and eliminates the possibility to receive from it stimuli

which lead to irritation and on the whole derange mental functions. This

explanation is mechanistic and goes back to the narrow localizationism

characteristic of psychiatrists of America, from where leucotomy was

imported to us.

The USSR officially banned the procedure in 1950 on the initiative of Gilyarovsky. Doctors in the Soviet Union concluded that the procedure was "contrary to the principles of humanity" and "'through lobotomy' an insane person is changed into an idiot". By the 1970s, numerous countries had banned the procedure, as had several US states.

In 1977 the US Congress, during the presidency of Jimmy Carter,

created the National Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of

Biomedical and Behavioral Research to investigate allegations that

psychosurgery—including lobotomy techniques—was used to control

minorities and restrain individual rights. The committee concluded that

some extremely limited and properly performed psychosurgery could have

positive effects.

There have been calls in the early 21st century for the Nobel Foundation

to rescind the prize it awarded to Moniz for developing lobotomy, a

decision that has been called an astounding error of judgment at the

time and one that psychiatry might still need to learn from, but the

Foundation declined to take action and has continued to host an article

defending the results of the procedure.

Notable cases

- Rosemary Kennedy, sister of President John F. Kennedy, underwent a lobotomy in 1941 that left her incapacitated and institutionalized for the rest of her life.

- Howard Dully wrote a memoir of his late-life discovery that he had been lobotomized in 1960 at age 12.

- New Zealand author and poet Janet Frame received a literary award in 1951 the day before a scheduled lobotomy was to take place, and it was never performed.

- Josef Hassid, a Polish violinist and composer, was diagnosed with schizophrenia and died at the age of 26 following a lobotomy.

- Swedish modernist painter Sigrid Hjertén died following a lobotomy in 1948.

- American playwright Tennessee Williams'

older sister Rose received a lobotomy that left her incapacitated for

life; the episode is said to have inspired characters and motifs in

certain works of his.

- It is often said that when an iron rod was accidentally driven through the head of Phineas Gage

in 1848, this constituted an "accidental lobotomy", or that this event

somehow inspired the development of surgical lobotomy a century later.

According to the only book-length study of Gage, careful inquiry turns

up no such link.

- In 2011, Daniel Nijensohn, an Argentine-born neurosurgeon at Yale, examined X-rays of Eva Perón and concluded that she underwent a lobotomy for the treatment of pain and anxiety in the last months of her life.

Literary and cinematic portrayals

Lobotomies

have been featured in several literary and cinematic presentations that

both reflected society's attitude towards the procedure and, at times,

changed it. Writers and film-makers have played a pivotal role in

turning public sentiment against the procedure.

- Robert Penn Warren's 1946 novel All the King's Men

describes a lobotomy as making "a Comanche brave look like a tyro with a

scalping knife", and portrays the surgeon as a repressed man who cannot

change others with love, so he instead resorts to "high-grade carpentry

work".

- Tennessee Williams criticized lobotomy in his play Suddenly, Last Summer (1958) because it was sometimes inflicted on homosexuals—to render them "morally sane".

In the play a wealthy matriarch offers the local mental hospital a

substantial donation if the hospital will give her niece a lobotomy,

which she hopes will stop the niece's shocking revelations about the

matriarch's son.

Warned that a lobotomy might not stop her niece's "babbling", she

responds, "That may be, maybe not, but after the operation who would believe her, Doctor?"

- In Ken Kesey's 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and its 1975 film adaptation, lobotomy is described as "frontal-lobe castration", a form of punishment and

control after which "There's nothin' in the face. Just like one of

those store dummies." In one patient, "You can see by his eyes how they

burned him out over there; his eyes are all smoked up and gray and

deserted inside."

- In Sylvia Plath's 1963 novel The Bell Jar, the protagonist reacts with horror to the "perpetual marble calm" of a lobotomized young woman.

- Elliott Baker's 1964 novel and 1966 film version, A Fine Madness,

portrays the dehumanizing lobotomy of a womanizing, quarrelsome poet

who, afterwards, is just as aggressive as ever. The surgeon is depicted

as an inhumane crackpot.

- The 1982 biopic film Frances depicts actress Frances Farmer (the subject of the film) undergoing transorbital lobotomy (though the idea

that a lobotomy was performed on Farmer, and that Freeman performed it,

has been criticized as having little or no factual foundation).

- The 2018 film The Mountain

centers around lobotomization, its cultural significance in the context

of 1950s America, and mid-century attitudes surrounding mental health

in general. The film interrogates the ethical and social implications of

the practice through the experiences of its protagonist, a young man

whose late mother had been lobotomized. The protagonist takes a job as a

medical photographer for the fictional Dr. Wallace Fiennes, portrayed by Jeff Goldblum. Fiennes is loosely based on Freeman.