He is currently the Co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies, the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, and a University Professor at Tufts University. Dennett is an atheist and secularist, a member of the Secular Coalition for America advisory board,[4] as well as an outspoken supporter of the Brights movement. Dennett is referred to as one of the "Four Horsemen of New Atheism", along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens.[5]

Early life and education

Dennett was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Ruth Marjorie (née Leck) and Daniel Clement Dennett, Jr.[6][7] Dennett spent part of his childhood in Lebanon, where, during World War II, his father was a covert counter-intelligence agent with the Office of Strategic Services posing as a cultural attaché to the American Embassy in Beirut.[8] When he was five, his mother took him back to Massachusetts after his father died in an unexplained plane crash.[9] Dennett says that he was first introduced to the notion of philosophy while attending summer camp at age 11, when a camp counselor said to him, "You know what you are, Daniel? You're a philosopher."[10]Dennett attended Phillips Exeter Academy and spent one year at Wesleyan University before receiving his Bachelor of Arts in philosophy from Harvard University in 1963. At Harvard University he was a student of W. V. Quine. In 1965, he received his Doctor of Philosophy in philosophy from the University of Oxford, where he studied under Gilbert Ryle and was a member of Christ Church. Dennett's sister is the investigative journalist Charlotte Dennett.[8]

Dennett describes himself as "an autodidact—or, more properly, the beneficiary of hundreds of hours of informal tutorials on all the fields that interest me, from some of the world's leading scientists."[11]

He is the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and a Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences.[12] He is a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry and a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism.[13] He was named 2004 Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association.[14]

In February 2010, he was named to the Freedom From Religion Foundation's Honorary Board of distinguished achievers.[15]

In 2012, he was awarded the Erasmus Prize, an annual award for a person who has made an exceptional contribution to European culture, society or social science, "for his ability to translate the cultural significance of science and technology to a broad audience."[16]

Philosophical views

Free will

While he is a confirmed compatibilist on free will, in "On Giving Libertarians What They Say They Want"—Chapter 15 of his 1978 book Brainstorms,[17] Dennett articulated the case for a two-stage model of decision making in contrast to libertarian views.The model of decision making I am proposing has the following feature: when we are faced with an important decision, a consideration-generator whose output is to some degree undetermined produces a series of considerations, some of which may of course be immediately rejected as irrelevant by the agent (consciously or unconsciously). Those considerations that are selected by the agent as having a more than negligible bearing on the decision then figure in a reasoning process, and if the agent is in the main reasonable, those considerations ultimately serve as predictors and explicators of the agent's final decision.[18]While other philosophers have developed two-stage models, including William James, Henri Poincaré, Arthur Holly Compton, and Henry Margenau, Dennett defends this model for the following reasons:

- First ... The intelligent selection, rejection, and weighing of the considerations that do occur to the subject is a matter of intelligence making the difference.

- Second, I think it installs indeterminism in the right place for the libertarian, if there is a right place at all.

- Third ... from the point of view of biological engineering, it is just more efficient and in the end more rational that decision making should occur in this way.

- A fourth observation in favor of the model is that it permits moral education to make a difference, without making all of the difference.

- Fifth—and I think this is perhaps the most important thing to be said in favor of this model—it provides some account of our important intuition that we are the authors of our moral decisions.

- Finally, the model I propose points to the multiplicity of decisions that encircle our moral decisions and suggests that in many cases our ultimate decision as to which way to act is less important phenomenologically as a contributor to our sense of free will than the prior decisions affecting our deliberation process itself: the decision, for instance, not to consider any further, to terminate deliberation; or the decision to ignore certain lines of inquiry.

These prior and subsidiary decisions contribute, I think, to our sense of ourselves as responsible free agents, roughly in the following way: I am faced with an important decision to make, and after a certain amount of deliberation, I say to myself: "That's enough. I've considered this matter enough and now I'm going to act," in the full knowledge that I could have considered further, in the full knowledge that the eventualities may prove that I decided in error, but with the acceptance of responsibility in any case.[19]Leading libertarian philosophers such as Robert Kane have rejected Dennett's model, specifically that random chance is directly involved in a decision, on the basis that they believe this eliminates the agent's motives and reasons, character and values, and feelings and desires. They claim that, if chance is the primary cause of decisions, then agents cannot be liable for resultant actions. Kane says:

[As Dennett admits,] a causal indeterminist view of this deliberative kind does not give us everything libertarians have wanted from free will. For [the agent] does not have complete control over what chance images and other thoughts enter his mind or influence his deliberation. They simply come as they please. [The agent] does have some control after the chance considerations have occurred.

But then there is no more chance involved. What happens from then on, how he reacts, is determined by desires and beliefs he already has. So it appears that he does not have control in the libertarian sense of what happens after the chance considerations occur as well. Libertarians require more than this for full responsibility and free will.[20]

Philosophy of mind

Dennett has remarked in several places (such as "Self-portrait", in Brainchildren) that his overall philosophical project has remained largely the same since his time at Oxford. He is primarily concerned with providing a philosophy of mind that is grounded in empirical research. In his original dissertation, Content and Consciousness, he broke up the problem of explaining the mind into the need for a theory of content and for a theory of consciousness. His approach to this project has also stayed true to this distinction. Just as Content and Consciousness has a bipartite structure, he similarly divided Brainstorms into two sections. He would later collect several essays on content inThe Intentional Stance and synthesize his views on consciousness into a unified theory in Consciousness Explained. These volumes respectively form the most extensive development of his views.[21]

In chapter 5 of Consciousness Explained Dennett describes his multiple drafts model of consciousness. He states that, "all varieties of perception—indeed all varieties of thought or mental activity—are accomplished in the brain by parallel, multitrack processes of interpretation and elaboration of sensory inputs. Information entering the nervous system is under continuous 'editorial revision.'" (p. 111). Later he asserts, "These yield, over the course of time, something rather like a narrative stream or sequence, which can be thought of as subject to continual editing by many processes distributed around the brain, ..." (p. 135, emphasis in the original).

In this work, Dennett's interest in the ability of evolution to explain some of the content-producing features of consciousness is already apparent, and this has since become an integral part of his program. He defends a theory known by some as Neural Darwinism. He also presents an argument against qualia; he argues that the concept is so confused that it cannot be put to any use or understood in any non-contradictory way, and therefore does not constitute a valid refutation of physicalism. His strategy mirrors his teacher Ryle's approach of redefining first person phenomena in third person terms, and denying the coherence of the concepts which this approach struggles with.

Dennett self-identifies with a few terms: "[Others] note that my 'avoidance of the standard philosophical terminology for discussing such matters' often creates problems for me; philosophers have a hard time figuring out what I am saying and what I am denying. My refusal to play ball with my colleagues is deliberate, of course, since I view the standard philosophical terminology as worse than useless—a major obstacle to progress since it consists of so many errors."[22]

In Consciousness Explained, he affirms "I am a sort of 'teleofunctionalist', of course, perhaps the original teleofunctionalist'". He goes on to say, "I am ready to come out of the closet as some sort of verificationist".

Evolutionary debate

Much of Dennett's work since the 1990s has been concerned with fleshing out his previous ideas by addressing the same topics from an evolutionary standpoint, from what distinguishes human minds from animal minds (Kinds of Minds), to how free will is compatible with a naturalist view of the world (Freedom Evolves).Dennett sees evolution by natural selection as an algorithmic process (though he spells out that algorithms as simple as long division often incorporate a significant degree of randomness).[23] This idea is in conflict with the evolutionary philosophy of paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who preferred to stress the "pluralism" of evolution (i.e., its dependence on many crucial factors, of which natural selection is only one).

Dennett's views on evolution are identified as being strongly adaptationist, in line with his theory of the intentional stance, and the evolutionary views of biologist Richard Dawkins. In Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Dennett showed himself even more willing than Dawkins to defend adaptationism in print, devoting an entire chapter to a criticism of the ideas of Gould. This stems from Gould's long-running public debate with E. O. Wilson and other evolutionary biologists over human sociobiology and its descendant evolutionary psychology, which Gould and Richard Lewontin opposed, but which Dennett advocated, together with Dawkins and Steven Pinker.[24] Strong disagreements have been launched against Dennett from Gould and his supporters, who allege that Dennett overstated his claims and misrepresented Gould's to reinforce what Gould describes as Dennett's "Darwinian fundamentalism".[25]

Dennett's theories have had a significant influence on the work of evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller.

An account of religion and morality

In Darwin's Dangerous Idea, Dennett writes that evolution can account for the origin of morality. He rejects the idea of the naturalistic fallacy as the idea that ethics is in some free-floating realm, writing that the fallacy is to rush from facts to values.In his 2006 book, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, Dennett attempts to account for religious belief naturalistically, explaining possible evolutionary reasons for the phenomenon of religious adherence. In this book he declares himself to be "a bright", and defends the term.

He has been doing research into clerics who are secretly atheists and how they rationalize their works. He found what he called a "Don't ask, don't tell" conspiracy because believers did not want to hear of loss of faith. That made unbelieving preachers feel isolated but they did not want to lose their jobs and sometimes their church-supplied lodgings and generally consoled themselves that they were doing good in their pastoral roles by providing comfort and required ritual.[26] The research, with Linda LaScola, was further extended to include other denominations and non-Christian clerics.[27]

Other philosophical views

He has also written about and advocated the notion of memetics as a philosophically useful tool, most recently in his "Brains, Computers, and Minds", a three part presentation through Harvard's MBB 2009 Distinguished Lecture Series.Personal life

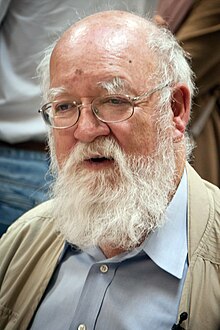

Dennett in Tahiti in 1984

Dennett married Susan Bell in 1962.[28] They live in North Andover, Massachusetts, and have a daughter, a son, and three grandchildren.[29] He is also an avid sailor.[30]

Selected works

- Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (MIT Press 1981) (ISBN 0-262-54037-1)

- Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting (MIT Press 1984) — on free will and determinism (ISBN 0-262-04077-8)

- The Mind's I (Bantam, Reissue edition 1985, with Douglas Hofstadter) (ISBN 0-553-34584-2)

- Content and Consciousness (Routledge & Kegan Paul Books Ltd; 2nd ed. January 1986) (ISBN 0-7102-0846-4)

- The Intentional Stance (6th printing), Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1996, ISBN 0-262-54053-3 (First published 1987)

- Consciousness Explained (Back Bay Books 1992) (ISBN 0-316-18066-1)

- Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (Simon & Schuster; reprint edition 1996) (ISBN 0-684-82471-X)

- Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness (Basic Books 1997) (ISBN 0-465-07351-4)

- Brainchildren: Essays on Designing Minds (Representation and Mind) (MIT Press 1998) (ISBN 0-262-04166-9) — A Collection of Essays 1984–1996

- Freedom Evolves (Viking Press 2003) (ISBN 0-670-03186-0)

- Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness (MIT Press 2005) (ISBN 0-262-04225-8)

- Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (Penguin Group 2006) (ISBN 0-670-03472-X).

- Neuroscience and Philosophy: Brain, Mind, and Language (Columbia University Press 2007) (ISBN 978-0-231-14044-7), co-authored with Maxwell Bennett, Peter Hacker, and John Searle

- Science and Religion (Oxford University Press 2010) (ISBN 0-199-73842-4), co-authored with Alvin Plantinga

- Intuition Pumps And Other Tools for Thinking (W. W. Norton & Company – May 6, 2013) (ISBN 0-393-08206-7)

- Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind (MIT Press – 2011) (ISBN 978-0-262-01582-0), co-authored with Matthew M. Hurley and Reginald B. Adams, Jr.