From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In statistics, a confidence interval (CI) is a type of interval estimate, computed from the statistics of the observed data, that might contain the true value of an unknown population parameter. The interval has an associated confidence level that, loosely speaking, quantifies the level of confidence that the parameter lies in the interval. More strictly speaking, the confidence level represents the frequency (i.e. the proportion) of possible confidence intervals that contain the true value of the unknown population parameter. In other words, if confidence intervals are constructed using a given confidence level from an infinite number of independent sample statistics, the proportion of those intervals that contain the true value of the parameter will be equal to the confidence level.

Confidence intervals consist of a range of potential values of the unknown population parameter.

However, the interval computed from a particular sample does not

necessarily include the true value of the parameter. Since the observed

data are random samples from the true population, the confidence

interval obtained from the data is also random.

The confidence level is designated prior to examining the data. Most commonly, the 95% confidence level is used. However, other confidence levels can be used, for example, 90% and 99%.

Factors affecting the width of the confidence interval include the size of the sample, the confidence level, and the variability in the sample. A larger sample will, all other things being equal, tend to produce a better estimate of the population parameter.

Confidence intervals were introduced to statistics by Jerzy Neyman in a paper published in 1937.

The confidence level is designated prior to examining the data. Most commonly, the 95% confidence level is used. However, other confidence levels can be used, for example, 90% and 99%.

Factors affecting the width of the confidence interval include the size of the sample, the confidence level, and the variability in the sample. A larger sample will, all other things being equal, tend to produce a better estimate of the population parameter.

Confidence intervals were introduced to statistics by Jerzy Neyman in a paper published in 1937.

Conceptual basis

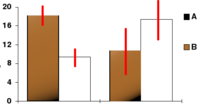

In this bar chart, the top ends of the brown bars indicate observed means and the red line segments

("error bars") represent the confidence intervals around them. Although

the error bars are shown as symmetric around the means, that is not

always the case. It is also important that in most graphs, the error

bars do not represent confidence intervals (e.g., they often represent

standard errors or standard deviations)

Introduction

Interval estimates can be contrasted with point estimates. A point estimate is a single value given as the estimate of a population parameter that is of interest, for example, the mean of some quantity. An interval estimate specifies instead a range within which the parameter is estimated to lie. Confidence intervals are commonly reported in tables or graphs along with point estimates of the same parameters, to show the reliability of the estimates.For example, a confidence interval can be used to describe how reliable survey results are. In a poll of election–voting intentions, the result might be that 40% of respondents intend to vote for a certain party. A 99% confidence interval for the proportion in the whole population having the same intention on the survey might be 30% to 50%. From the same data one may calculate a 90% confidence interval, which in this case might be 37% to 43%. A major factor determining the length of a confidence interval is the size of the sample used in the estimation procedure, for example, the number of people taking part in a survey.

Meaning and interpretation

Various interpretations of a confidence interval can be given (taking the 90% confidence interval as an example in the following).- The confidence interval can be expressed in terms of samples (or repeated samples): "Were this procedure to be repeated on numerous samples, the fraction of calculated confidence intervals (which would differ for each sample) that encompass the true population parameter would tend toward 90%."

- The confidence interval can be expressed in terms of a single sample: "There is a 90% probability that the calculated confidence interval from some future experiment encompasses the true value of the population parameter." Note this is a probability statement about the confidence interval, not the population parameter. This considers the probability associated with a confidence interval from a pre-experiment point of view, in the same context in which arguments for the random allocation of treatments to study items are made. Here the experimenter sets out the way in which they intend to calculate a confidence interval and to know, before they do the actual experiment, that the interval they will end up calculating has a particular chance of covering the true but unknown value. This is very similar to the "repeated sample" interpretation above, except that it avoids relying on considering hypothetical repeats of a sampling procedure that may not be repeatable in any meaningful sense. See Neyman construction.

- The explanation of a confidence interval can amount to something like: "The confidence interval represents values for the population parameter for which the difference between the parameter and the observed estimate is not statistically significant at the 10% level". In fact, this relates to one particular way in which a confidence interval may be constructed.

Misunderstandings

Confidence intervals are frequently misunderstood, and published studies have shown that even professional scientists often misinterpret them.- A 95% confidence interval does not mean that for a given

realized interval there is a 95% probability that the population

parameter lies within the interval (i.e., a 95% probability that the

interval covers the population parameter).

According to the frequentist interpretation, once an experiment is done

and an interval calculated, this interval either covers the parameter

value or it does not; it is no longer a matter of probability. The 95%

probability relates to the reliability of the estimation procedure, not

to a specific calculated interval. Neyman himself (the original proponent of confidence intervals) made this point in his original paper:

"It will be noticed that in the above description, the probability statements refer to the problems of estimation with which the statistician will be concerned in the future. In fact, I have repeatedly stated that the frequency of correct results will tend to α. Consider now the case when a sample is already drawn, and the calculations have given [particular limits]. Can we say that in this particular case the probability of the true value [falling between these limits] is equal to α? The answer is obviously in the negative. The parameter is an unknown constant, and no probability statement concerning its value may be made..."

- Deborah Mayo expands on this further as follows:

"It must be stressed, however, that having seen the value [of the data], Neyman-Pearson theory never permits one to conclude that the specific confidence interval formed covers the true value of 0 with either (1 − α)100% probability or (1 − α)100% degree of confidence. Seidenfeld's remark seems rooted in a (not uncommon) desire for Neyman-Pearson confidence intervals to provide something which they cannot legitimately provide; namely, a measure of the degree of probability, belief, or support that an unknown parameter value lies in a specific interval. Following Savage (1962), the probability that a parameter lies in a specific interval may be referred to as a measure of final precision. While a measure of final precision may seem desirable, and while confidence levels are often (wrongly) interpreted as providing such a measure, no such interpretation is warranted. Admittedly, such a misinterpretation is encouraged by the word 'confidence'."

- A 95% confidence interval does not mean that 95% of the sample data lie within the interval.

- A confidence interval is not a definitive range of plausible values for the sample parameter, though it may be understood as an estimate of plausible values for the population parameter.

- A particular confidence interval of 95% calculated from an experiment does not mean that there is a 95% probability of a sample parameter from a repeat of the experiment falling within this interval.

Philosophical issues

The principle behind confidence intervals was formulated to provide an answer to the question raised in statistical inference of how to deal with the uncertainty inherent in results derived from data that are themselves only a randomly selected subset of a population. There are other answers, notably that provided by Bayesian inference in the form of credible intervals. Confidence intervals correspond to a chosen rule for determining the confidence bounds, where this rule is essentially determined before any data are obtained, or before an experiment is done. The rule is defined such that over all possible datasets that might be obtained, there is a high probability ("high" is specifically quantified) that the interval determined by the rule will include the true value of the quantity under consideration. The Bayesian approach appears to offer intervals that can, subject to acceptance of an interpretation of "probability" as Bayesian probability, be interpreted as meaning that the specific interval calculated from a given dataset has a particular probability of including the true value, conditional on the data and other information available. The confidence interval approach does not allow this since in this formulation and at this same stage, both the bounds of the interval and the true values are fixed values, and there is no randomness involved. On the other hand, the Bayesian approach is only as valid as the prior probability used in the computation, whereas the confidence interval does not depend on assumptions about the prior probability.The questions concerning how an interval expressing uncertainty in an estimate might be formulated, and of how such intervals might be interpreted, are not strictly mathematical problems and are philosophically problematic. Mathematics can take over once the basic principles of an approach to 'inference' have been established, but it has only a limited role in saying why one approach should be preferred to another: For example, a confidence level of 95% is often used in the biological sciences, but this is a matter of convention or arbitration. In the physical sciences, a much higher level may be used.

Relationship with other statistical topics

Statistical hypothesis testing

Confidence intervals are closely related to statistical significance testing. For example, if for some estimated parameter θ one wants to test the null hypothesis that θ = 0 against the alternative that θ ≠ 0, then this test can be performed by determining whether the confidence interval for θ contains 0.More generally, given the availability of a hypothesis testing procedure that can test the null hypothesis θ = θ0 against the alternative that θ ≠ θ0 for any value of θ0, then a confidence interval with confidence level γ = 1 − α can be defined as containing any number θ0 for which the corresponding null hypothesis is not rejected at significance level α.

If the estimates of two parameters (for example, the mean values of a variable in two independent groups) have confidence intervals that do not overlap, then the difference between the two values is more significant than that indicated by the individual values of α. So, this "test" is too conservative and can lead to a result that is more significant than the individual values of α would indicate. If two confidence intervals overlap, the two means still may be significantly different. Accordingly, and consistent with the Mantel-Haenszel Chi-squared test, is a proposed fix whereby one reduces the error bounds for the two means by multiplying them by the square root of ½ (0.707107) before making the comparison.

While the formulations of the notions of confidence intervals and of statistical hypothesis testing are distinct, they are in some senses related and to some extent complementary. While not all confidence intervals are constructed in this way, one general purpose approach to constructing confidence intervals is to define a 100(1 − α)% confidence interval to consist of all those values θ0 for which a test of the hypothesis θ = θ0 is not rejected at a significance level of 100α%. Such an approach may not always be available since it presupposes the practical availability of an appropriate significance test. Naturally, any assumptions required for the significance test would carry over to the confidence intervals.

It may be convenient to make the general correspondence that parameter values within a confidence interval are equivalent to those values that would not be rejected by a hypothesis test, but this would be dangerous. In many instances the confidence intervals that are quoted are only approximately valid, perhaps derived from "plus or minus twice the standard error," and the implications of this for the supposedly corresponding hypothesis tests are usually unknown.

It is worth noting that the confidence interval for a parameter is not the same as the acceptance region of a test for this parameter, as is sometimes thought. The confidence interval is part of the parameter space, whereas the acceptance region is part of the sample space. For the same reason, the confidence level is not the same as the complementary probability of the level of significance.

Confidence region

Confidence regions generalize the confidence interval concept to deal with multiple quantities. Such regions can indicate not only the extent of likely sampling errors but can also reveal whether (for example) it is the case that if the estimate for one quantity is unreliable, then the other is also likely to be unreliable.Confidence band

A confidence band is used in statistical analysis to represent the uncertainty in an estimate of a curve or function based on limited or noisy data. Similarly, a prediction band is used to represent the uncertainty about the value of a new data point on the curve, but subject to noise. Confidence and prediction bands are often used as part of the graphical presentation of results of a regression analysis.Confidence bands are closely related to confidence intervals, which represent the uncertainty in an estimate of a single numerical value. "As confidence intervals, by construction, only refer to a single point, they are narrower (at this point) than a confidence band which is supposed to hold simultaneously at many points."

Basic steps

This example assumes that the samples are drawn from a Gaussian distribution. The basic breakdown of how to calculate a confidence interval for a population mean is as follows:- 1. Identify the sample mean, .

- 2. Identify whether the standard deviation is known, , or unknown, s.

- If standard deviation is known then , where is the CDF of the Standard normal distribution, used as the critical value. This value is only dependent on the confidence level for the test. Typical two sided confidence levels are:

-

-

C z* 99% 2.576 98% 2.326 95% 1.96 90% 1.645

-

- If the standard deviation is unknown then Student's t distribution is used as the critical value. This value is dependent on the confidence level (C) for the test and degrees of freedom. The degrees of freedom are found by subtracting one from the number of observations, n − 1. The critical value is found from the t-distribution table. In this table the critical value is written as tα(r), where r is the degrees of freedom and .

- 3. Plug the found values into the appropriate equations:

- For a known standard deviation:

- For an unknown standard deviation:

- 4. The final step is to interpret the answer. The confidence interval represents values for the population mean for which the difference between the mean and the observed estimate is not statistically significant at the 100%-__% level.

Statistical theory

Definition

Let X be a random sample from a probability distribution with statistical parameters θ, which is a quantity to be estimated, and φ, representing quantities that are not of immediate interest. A confidence interval for the parameter θ, with confidence level or confidence coefficient γ, is an interval with random endpoints (u(X), v(X)), determined by the pair of random variables u(X) and v(X), with the property:Here Prθ,φ indicates the probability distribution of X characterised by (θ, φ). An important part of this specification is that the random interval (u(X), v(X)) covers the unknown value θ with a high probability no matter what the true value of θ actually is.

Note that here Prθ,φ need not refer to an explicitly given parameterized family of distributions, although it often does. Just as the random variable X notionally corresponds to other possible realizations of x from the same population or from the same version of reality, the parameters (θ, φ) indicate that we need to consider other versions of reality in which the distribution of X might have different characteristics.

In a specific situation, when x is the outcome of the sample X, the interval (u(x), v(x)) is also referred to as a confidence interval for θ. Note that it is no longer possible to say that the (observed) interval (u(x), v(x)) has probability γ to contain the parameter θ. This observed interval is just one realization of all possible intervals for which the probability statement holds.

Approximate confidence intervals

In many applications, confidence intervals that have exactly the required confidence level are hard to construct. But practically useful intervals can still be found: the rule for constructing the interval may be accepted as providing a confidence interval at level γ ifDesirable properties

When applying standard statistical procedures, there will often be standard ways of constructing confidence intervals. These will have been devised so as to meet certain desirable properties, which will hold given that the assumptions on which the procedure rely are true. These desirable properties may be described as: validity, optimality, and invariance. Of these "validity" is most important, followed closely by "optimality". "Invariance" may be considered as a property of the method of derivation of a confidence interval rather than of the rule for constructing the interval. In non-standard applications, the same desirable properties would be sought.- Validity. This means that the nominal coverage probability (confidence level) of the confidence interval should hold, either exactly or to a good approximation.

- Optimality. This means that the rule for constructing the confidence interval should make as much use of the information in the data-set as possible. Recall that one could throw away half of a dataset and still be able to derive a valid confidence interval. One way of assessing optimality is by the length of the interval so that a rule for constructing a confidence interval is judged better than another if it leads to intervals whose lengths are typically shorter.

- Invariance. In many applications, the quantity being estimated might not be tightly defined as such. For example, a survey might result in an estimate of the median income in a population, but it might equally be considered as providing an estimate of the logarithm of the median income, given that this is a common scale for presenting graphical results. It would be desirable that the method used for constructing a confidence interval for the median income would give equivalent results when applied to constructing a confidence interval for the logarithm of the median income: specifically the values at the ends of the latter interval would be the logarithms of the values at the ends of former interval.

Methods of derivation

For non-standard applications, there are several routes that might be taken to derive a rule for the construction of confidence intervals. Established rules for standard procedures might be justified or explained via several of these routes. Typically a rule for constructing confidence intervals is closely tied to a particular way of finding a point estimate of the quantity being considered.- Summary statistics

- This is closely related to the method of moments for estimation. A simple example arises where the quantity to be estimated is the mean, in which case a natural estimate is the sample mean. The usual arguments indicate that the sample variance can be used to estimate the variance of the sample mean. A confidence interval for the true mean can be constructed centered on the sample mean with a width which is a multiple of the square root of the sample variance.

- Likelihood theory

- Where estimates are constructed using the maximum likelihood principle, the theory for this provides two ways of constructing confidence intervals or confidence regions for the estimates. One way is by using Wilks's theorem to find all the possible values of that fulfill the following restriction:

- Estimating equations

- The estimation approach here can be considered as both a generalization of the method of moments and a generalization of the maximum likelihood approach. There are corresponding generalizations of the results of maximum likelihood theory that allow confidence intervals to be constructed based on estimates derived from estimating equations.

- Hypothesis testing

- If significance tests are available for general values of a parameter, then confidence intervals/regions can be constructed by including in the 100p% confidence region all those points for which the significance test of the null hypothesis that the true value is the given value is not rejected at a significance level of (1 − p).

- Bootstrapping

- In situations where the distributional assumptions for that above methods are uncertain or violated, resampling methods allow construction of confidence intervals or prediction intervals. The observed data distribution and the internal correlations are used as the surrogate for the correlations in the wider population.

Examples

Practical example

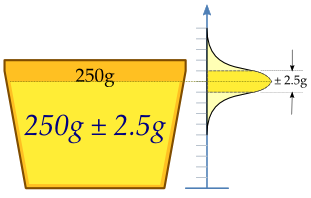

A machine fills cups with a liquid, and is supposed to be adjusted so that the content of the cups is 250 g of liquid. As the machine cannot fill every cup with exactly 250.0 g, the content added to individual cups shows some variation, and is considered a random variable X. This variation is assumed to be normally distributed around the desired average of 250 g, with a standard deviation, σ, of 2.5 g. To determine if the machine is adequately calibrated, a sample of n = 25 cups of liquid is chosen at random and the cups are weighed. The resulting measured masses of liquid are X1, ..., X25, a random sample from X.

To get an impression of the expectation μ, it is sufficient to give an estimate. The appropriate estimator is the sample mean:

In our case we may determine the endpoints by considering that the sample mean X from a normally distributed sample is also normally distributed, with the same expectation μ, but with a standard error of:

We take 1 − α = 0.95, for example. So we have:

Interpretation

This might be interpreted as: with probability 0.95 we will find a confidence interval in which the value of parameter μ will be between the stochastic endpoints

The blue vertical line segments represent 50 realizations of a confidence interval for the population mean μ,

represented as a red horizontal dashed line; note that some confidence

intervals do not contain the population mean, as expected.

In other words, the 95% confidence interval is between the lower endpoint 249.22 g and the upper endpoint 251.18 g.

As the desired value 250 of μ is within the resulted confidence interval, there is no reason to believe the machine is wrongly calibrated.

The calculated interval has fixed endpoints, where μ might be in between (or not). Thus this event has probability either 0 or 1. One cannot say: "with probability (1 − α) the parameter μ lies in the confidence interval." One only knows that by repetition in 100(1 − α) % of the cases, μ will be in the calculated interval. In 100α% of the cases however it does not. And unfortunately one does not know in which of the cases this happens. That is (instead of using the term "probability") why one can say: "with confidence level 100(1 − α) %, μ lies in the confidence interval."

The maximum error is calculated to be 0.98 since it is the difference between the value that we are confident of with upper or lower endpoint.

The figure on the right shows 50 realizations of a confidence interval for a given population mean μ. If we randomly choose one realization, the probability is 95% we end up having chosen an interval that contains the parameter; however, we may be unlucky and have picked the wrong one. We will never know; we are stuck with our interval.

Theoretical example

Suppose {X1, ..., Xn} is an independent sample from a normally distributed population with unknown (parameters) mean μ and variance σ2. LetConsequently,

After observing the sample we find values x for X and s for S, from which we compute the confidence interval

Alternatives and critiques

Confidence intervals are one method of interval estimation, and the most widely used in frequentist statistics. An analogous concept in Bayesian statistics is credible intervals, while an alternative frequentist method is that of prediction intervals which, rather than estimating parameters, estimate the outcome of future samples. For other approaches to expressing uncertainty using intervals, see interval estimation.Comparison to prediction intervals

A prediction interval for a random variable is defined similarly to a confidence interval for a statistical parameter. Consider an additional random variable Y which may or may not be statistically dependent on the random sample X. Then (u(X), v(X)) provides a prediction interval for the as-yet-to-be observed value y of Y ifComparison to Bayesian interval estimates

A Bayesian interval estimate is called a credible interval. Using much of the same notation as above, the definition of a credible interval for the unknown true value of θ is, for a given γ,- The definition of a confidence interval involves probabilities calculated from the distribution of X for a given (θ, φ) (or conditional on these values) and the condition needs to hold for all values of (θ, φ).

- The definition of a credible interval involves probabilities calculated from the distribution of Θ conditional on the observed values of X = x and marginalised (or averaged) over the values of Φ, where this last quantity is the random variable corresponding to the uncertainty about the nuisance parameters in φ.

In some simple standard cases, the intervals produced as confidence and credible intervals from the same data set can be identical. They are very different if informative prior information is included in the Bayesian analysis, and may be very different for some parts of the space of possible data even if the Bayesian prior is relatively uninformative.

There is disagreement about which of these methods produces the most useful results: the mathematics of the computations are rarely in question–confidence intervals being based on sampling distributions, credible intervals being based on Bayes' theorem–but the application of these methods, the utility and interpretation of the produced statistics, is debated.

An approximate confidence interval for a population mean can be constructed for random variables that are not normally distributed in the population, relying on the central limit theorem, if the sample sizes and counts are big enough. The formulae are identical to the case above (where the sample mean is actually normally distributed about the population mean). The approximation will be quite good with only a few dozen observations in the sample if the probability distribution of the random variable is not too different from the normal distribution (e.g. its cumulative distribution function does not have any discontinuities and its skewness is moderate).

One type of sample mean is the mean of an indicator variable, which takes on the value 1 for true and the value 0 for false. The mean of such a variable is equal to the proportion that has the variable equal to one (both in the population and in any sample). This is a useful property of indicator variables, especially for hypothesis testing. To apply the central limit theorem, one must use a large enough sample. A rough rule of thumb is that one should see at least 5 cases in which the indicator is 1 and at least 5 in which it is 0. Confidence intervals constructed using the above formulae may include negative numbers or numbers greater than 1, but proportions obviously cannot be negative or exceed 1. Additionally, sample proportions can only take on a finite number of values, so the central limit theorem and the normal distribution are not the best tools for building a confidence interval.

Counter-examples

Since confidence interval theory was proposed, a number of counter-examples to the theory have been developed to show how the interpretation of confidence intervals can be problematic, at least if one interprets them naïvely.Confidence procedure for uniform location

Welch presented an example which clearly shows the difference between the theory of confidence intervals and other theories of interval estimation (including Fisher's fiducial intervals and objective Bayesian intervals). Robinson called this example "[p]ossibly the best known counterexample for Neyman's version of confidence interval theory." To Welch, it showed the superiority of confidence interval theory; to critics of the theory, it shows a deficiency. Here we present a simplified version.Suppose that are independent observations from a Uniform(θ − 1/2, θ + 1/2) distribution. Then the optimal 50% confidence procedure is

However, when , intervals from the first procedure are guaranteed to contain the true value : Therefore, the nominal 50% confidence coefficient is unrelated to the uncertainty we should have that a specific interval contains the true value. The second procedure does not have this property.

Moreover, when the first procedure generates a very short interval, this indicates that are very close together and hence only offer the information in a single data point. Yet the first interval will exclude almost all reasonable values of the parameter due to its short width. The second procedure does not have this property.

The two counter-intuitive properties of the first procedure — 100% coverage when are far apart and almost 0% coverage when are close together — balance out to yield 50% coverage on average. However, despite the first procedure being optimal, its intervals offer neither an assessment of the precision of the estimate nor an assessment of the uncertainty one should have that the interval contains the true value.

This counter-example is used to argue against naïve interpretations of confidence intervals. If a confidence procedure is asserted to have properties beyond that of the nominal coverage (such as relation to precision, or a relationship with Bayesian inference), those properties must be proved; they do not follow from the fact that a procedure is a confidence procedure.

Confidence procedure for ω2

Steiger suggested a number of confidence procedures for common effect size measures in ANOVA. Morey et al. point out that several of these confidence procedures, including the one for ω2, have the property that as the F statistic becomes increasingly small — indicating misfit with all possible values of ω2 — the confidence interval shrinks and can even contain only the single value ω2=0; that is, the CI is infinitesimally narrow (this occurs when for a CI).This behavior is consistent with the relationship between the confidence procedure and significance testing: as F becomes so small that the group means are much closer together than we would expect by chance, a significance test might indicate rejection for most or all values of ω2. Hence the interval will be very narrow or even empty (or, by a convention suggested by Steiger, containing only 0). However, this does not indicate that the estimate of ω2 is very precise. In a sense, it indicates the opposite: that the trustworthiness of the results themselves may be in doubt. This is contrary to the common interpretation of confidence intervals that they reveal the precision of the estimate.

![{\begin{aligned}\Phi (z)&=P(Z\leq z)=1-{\tfrac {\alpha }{2}}=0.975,\\[6pt]z&=\Phi ^{-1}(\Phi (z))=\Phi ^{-1}(0.975)=1.96,\end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0e80e68d525d87d1b722d1150abda18cecb8f684)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}0.95&=1-\alpha =P(-z\leq Z\leq z)=P\left(-1.96\leq {\frac {{\bar {X}}-\mu }{\sigma /{\sqrt {n}}}}\leq 1.96\right)\\[6pt]&=P\left({\bar {X}}-1.96{\frac {\sigma }{\sqrt {n}}}\leq \mu \leq {\bar {X}}+1.96{\frac {\sigma }{\sqrt {n}}}\right).\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b25dd48d19a407eef29c8dd5ce96b08604aac220)

![\left[{\bar {x}}-{\frac {cs}{\sqrt {n}}},{\bar {x}}+{\frac {cs}{\sqrt {n}}}\right],\,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ad373a73808a03f9d480fb52fbd71ba3f3d8fa74)

![{\displaystyle {\bar {X}}\pm {\begin{cases}{\dfrac {|X_{1}-X_{2}|}{2}}&{\text{if }}|X_{1}-X_{2}|<1/2\\[8pt]{\dfrac {1-|X_{1}-X_{2}|}{2}}&{\text{if }}|X_{1}-X_{2}|\geq 1/2.\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/80260117bd9ee1f05d0928e0b5697663a297ecbc)