The stages used in dialectical behavior therapy

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy designed to help people suffering from borderline personality disorder

(BPD). It has also been used to treat mood disorders as well as those

who need to change patterns of behavior that are not helpful, such as self-harm, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse.

This approach is designed to help people increase their emotional and

cognitive regulation by learning about the triggers that lead to

reactive states and helping to assess which coping skills to apply in

the sequence of events, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors to help avoid

undesired reactions.

A modified form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), DBT was developed in the late 1980s by Marsha M. Linehan, a psychology researcher at the University of Washington,

to treat people with borderline personality disorder and chronically

suicidal individuals. Research on its effectiveness in treating other

conditions has been fruitful; DBT has been used to treat people with depression, drug and alcohol problems, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injuries (TBI), binge-eating disorder, and mood disorders. Research indicates DBT might help patients with symptoms and behaviors associated with spectrum mood disorders, including self-injury. Recent work also suggests its effectiveness with sexual abuse survivors and chemical dependency.

DBT combines standard cognitive behavioral techniques for emotion regulation and reality-testing with concepts of distress tolerance, acceptance, and mindful awareness largely derived from Buddhist meditative practice. DBT is based upon the biosocial theory of mental illness and is the first therapy that has been experimentally demonstrated to be generally effective in treating BPD.

The first randomized clinical trial of DBT showed reduced rates of

suicidal gestures, psychiatric hospitalizations, and treatment drop-outs

when compared to treatment as usual. A meta-analysis found that DBT reached moderate effects in individuals with borderline personality disorder.

Overview

Linehan

observed "burn-out" in therapists after coping with "non-motivated"

patients who repudiated cooperation in successful treatment. Her first

core insight was to recognize that the chronically suicidal patients she

studied had been raised in profoundly invalidating environments, and,

therefore, required a climate of loving-kindness and somewhat unconditional acceptance (not Carl Rogers' positive humanist approach, but Thích Nhất Hạnh's metaphysically neutral one), in which to develop a successful therapeutic alliance.

Her second insight involved the need for a commensurate commitment from

patients, who needed to be willing to accept their dire level of

emotional dysfunction.

DBT strives to have the patient view the therapist as an ally rather than an adversary

in the treatment of psychological issues. Accordingly, the therapist

aims to accept and validate the client's feelings at any given time,

while, nonetheless, informing the client that some feelings and

behaviors are maladaptive, and showing them better alternatives. DBT focuses on the client acquiring new skills and changing their behaviors, with the ultimate goal of achieving a "life worth living", as defined by the patient.

In DBT's biosocial theory of BPD, clients have a biological predisposition for emotional dysregulation, and their social environment validates maladaptive behavior.

Linehan and others combined a commitment to the core conditions of acceptance and change through the principle of dialectics

(in which thesis and antithesis are synthesized) and assembled an array

of skills for emotional self-regulation drawn from Western

psychological traditions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and an interpersonal variant, "assertiveness training", and Eastern meditative traditions, such as Buddhist mindfulness meditation.

One of her contributions was to alter the adversarial nature of the

therapist-client relationship in favor of an alliance based on intersubjective tough love.

All DBT can be said to involve 4 components:

- Individual – The therapist and patient discuss issues that come up during the week (recorded on diary cards) and follow a treatment target hierarchy. Self-injurious and suicidal behaviors, or life-threatening behaviors, take first priority. Second in priority are behaviors which, while not directly harmful to self or others, interfere with the course of treatment. These behaviors are known as therapy-interfering behaviors. Third in priority are quality of life issues and working towards improving one's life generally. During the individual therapy, the therapist and patient work towards improving skill use. Often, a skills group is discussed and obstacles to acting skillfully are addressed.

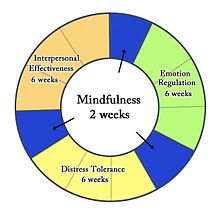

- Group – A group ordinarily meets once weekly for two to two and a half hours and learns to use specific skills that are broken down into four skill modules: core mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance.

- Therapist Consultation Team – A therapist consultation team includes all therapists providing DBT. The meeting occurs weekly and serves to support the therapist in providing the treatment.

- Phone Coaching – Phone coaching is designed to help generalize skills into the patient's daily life. Phone coaching is brief and limited to a focus on skills.

No one component is used by itself; the individual component is

considered necessary to keep suicidal urges or uncontrolled emotional

issues from disrupting group sessions, while the group sessions teach

the skills unique to DBT, and also provide practice with regulating

emotions and behavior in a social context. DBT skills training alone is being used to address treatment goals in some clinical settings, and the broader goal of emotion regulation that is seen in DBT has allowed it to be used in new settings, for example, supporting parenting.

Four modules

Mindfulness

A diagram used in DBT, showing that the Wise Mind is the overlap of the emotional mind and the reasonable mind.

Mindfulness is one of the core ideas behind all elements of DBT. It

is considered a foundation for the other skills taught in DBT, because

it helps individuals accept and tolerate the powerful emotions they may

feel when challenging their habits or exposing themselves to upsetting

situations. The concept of mindfulness and the meditative exercises used

to teach it are derived from traditional Buddhist practice, though the version taught in DBT does not involve any religious or metaphysical

concepts. Within DBT it is the capacity to pay attention,

nonjudgmentally, to the present moment; about living in the moment,

experiencing one's emotions and senses fully, yet with perspective. The

practice of mindfulness can also be intended to make people more aware

of their environments through their 5 senses: touch, smell, sight,

taste, and sound. Mindfulness relies heavily on the principle of acceptance, sometimes referred to as "radical acceptance".

Acceptance skills rely on the patient’s ability to view situations

with no judgment, and to accept situations and their accompanying

emotions. This causes less distress overall, which can result in reduced discomfort and symptomology.

Acceptance and Change

The

first few sessions of DBT introduce the dialectic of acceptance and

change. The patient must first become comfortable with the idea of

therapy; once the patient and therapist have established a trusting

relationship, DBT techniques can flourish. An essential part of learning

acceptance is to first grasp the idea of radical acceptance: radical

acceptance embraces the idea that one should face situations, both

positive and negative, without judgment.

Acceptance also incorporates mindfulness and emotional regulation

skills, which depend on the idea of radical acceptance. These skills,

specifically, are what set DBT apart from other therapies.

Often, after a patient becomes familiar with the idea of

acceptance, they will accompany it with change. DBT has five specific

states of change which the therapist will review with the patient:

precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.

Precontemplation is the first stage, in which the patient is completely

unaware of their problem. In the second stage, contemplation, the

patient realizes the reality of their illness: this is not an action,

but a realization. It is not until the third stage, preparation, that

the patient is likely to take action, and prepares to move forward. This

could be as simple as researching or contacting therapists. Finally, in

stage 4, the patient takes action and receives treatment. In the final

stage, maintenance, the patient must strengthen their change in order to

prevent relapse. After grasping acceptance and change, a patient can

fully advance to mindfulness techniques.

"What" skills:

- Observe

- This is used to nonjudgmentally observe one's environment within or outside oneself. It is helpful in understanding what is going on in any given situation.

- DBT recommends developing a "teflon mind", the ability to let feelings and experiences pass without sticking in the mind.

- Describe

- This is used to express what one has observed with the observe skill. It is to be used without judgmental statements. This helps with letting others know what one has observed. Once the environment or inner state of mind has been observed with 5 senses, the individual can put words to observations and thus better understand the environment.

- Participate

- This is used to become fully focused on, and involved in, the activity that one is doing.

"How" skills (How to do Mindful Meditation):

There are many "scripted" meditations

available on YouTube; for example: The 3 Minute Meditation; or The

Body Scan. How to do it (The Body Scan): You listen to the body scan

and you allow your mind to focus on each aspect of your physical self,

usually starting at your toes and ending at the top of your head. As

you listen to the body scan and allow your mind to focus in on the body,

you will notice your "busy mind" will come into consciousness. You

will notice that thoughts and feelings will attempt to distract you from

focusing on each part of your body. You will notice that some of the

thoughts and feelings may be distressing to you. You may want to stop

the meditation because it might be very painful emotionally or

physically or because you are having negative or busy thoughts.

Sometimes memories may surface and they may also be difficult

emotionally to accept. How to do Mindful Meditation involves learning

to acknowledge the thoughts, feelings and memories without needing to

fight them or chase them away. The paradox: If we try to fight them,

they seem to get bigger; but when we move into acceptance, they seem to

get smaller. We enter the mindfulness meditation body scan, 3 minute

meditation or other meditation sessions with no goals and with a

non-striving stance. Again, if we enter with a goal to "fix my problems

by meditating", that goal and pressure to fix something tends to make

the problems bigger. To enter the meditation with a

non-goal/non-striving attitude, so having no expectations,

paradoxically, usually results in a reduction of stress, pain and other

symptoms.

- Nonjudgmentally

- This is the action of describing the facts, and not thinking in terms of "good" or "bad," "fair," or "unfair." These are judgments, not factual descriptions. Being nonjudgmental helps you to get your point across in an effective manner without adding a judgment that someone else might disagree with.

- One-mindfully

- This is used to focus on one thing. One-mindfully is helpful in keeping one's mind from straying into "emotion" by a lack of focus.

- Effectively

- This is simply doing what works. It is a very broad-ranged skill and can be applied to any other skill to aid in being successful with said skill.

Distress tolerance

Many current approaches to mental health treatment focus on changing

distressing events and circumstances such as dealing with the death of a

loved one, loss of a job, serious illness, terrorist attacks and other

traumatic events.

They have paid little attention to accepting, finding meaning for, and

tolerating distress. This task has generally been tackled by

person-centered, psychodynamic, psychoanalytic, gestalt, or narrative

therapies, along with religious and spiritual communities and leaders.

Dialectical behavior therapy emphasizes learning to bear pain

skillfully.

Distress tolerance skills constitute a natural development from

DBT mindfulness skills. They have to do with the ability to accept, in a

non-evaluative and nonjudgmental fashion, both oneself and the current

situation. Since this is a non-judgmental stance, this means that it is

not one of approval or resignation. The goal is to become capable of

calmly recognizing negative situations and their impact, rather than

becoming overwhelmed or hiding from them. This allows individuals to

make wise decisions about whether and how to take action, rather than

falling into the intense, desperate, and often destructive emotional

reactions that are part of borderline personality disorder.

Distract with ACCEPTS

This is a skill used to distract oneself temporarily from unpleasant emotions.

-

- Activities – Use positive activities that you enjoy.

- Contribute – Help out others or your community.

- Comparisons – Compare yourself either to people that are less fortunate or to how you used to be when you were in a worse state.

- Emotions (other) – cause yourself to feel something different by provoking your sense of humor or happiness with corresponding activities.

- Push away – Put your situation on the back-burner for a while. Put something else temporarily first in your mind.

- Thoughts (other) – Force your mind to think about something else.

- Sensations (other) – Do something that has an intense feeling other than what you are feeling, like a cold shower or a spicy candy.

- Self-soothe

- This is a skill in which one behaves in a comforting, nurturing, kind, and gentle way to oneself. You use it by doing something that is soothing to you. It is used in moments of distress or agitation. New York Jets wide receiver Brandon Marshall, who was diagnosed with BPD in 2011 and is a strong advocate for DBT, cited activities such as prayer and listening to jazz music as instrumental in his treatment.

IMPROVE the moment

This skill is used in moments of distress to help one relax.

-

- Imagery – Imagine relaxing scenes, things going well, or other things that please you.

- Meaning – Find some purpose or meaning in what you are feeling.

- Prayer – Either pray to whomever you worship, or, if not religious, chant a personal mantra.

- Relaxation – Relax your muscles, breathe deeply; use with self-soothing.

- One thing in the moment – Focus your entire attention on what you are doing right now. Keep yourself in the present.

- Vacation (brief) – Take a break from it all for a short period of time.

- Encouragement – Cheerlead yourself. Tell yourself you can make it through this and cope as it will assist your resilience and reduce your vulnerability.

- Pros and cons

- Think about the positive and negative things about not tolerating distress.

- Radical acceptance

- Let go of fighting reality. Accept your situation for what it is.

- Turning the mind

- Turn your mind toward an acceptance stance. It should be used with radical acceptance.

- Willingness vs. willfulness

- Be willing and open to do what is effective. Let go of a willful stance which goes against acceptance. Keep your eye on the goal in front of you.

Emotion regulation

Individuals with borderline personality disorder and suicidal individuals are frequently emotionally intense and labile.

They can be angry, intensely frustrated, depressed, or anxious. This

suggests that these clients might benefit from help in learning to

regulate their emotions. Dialectical behavior therapy skills for emotion

regulation include:

- Identify and label emotions

- Identify obstacles to changing emotions

- Reduce vulnerability to emotion mind

- Increase positive emotional events

- Increase mindfulness to current emotions

- Take opposite action

- Apply distress tolerance techniques

Emotional regulation skills are based on the theory that intense

emotions are a conditioned response to troublesome experiences, the

conditioned stimulus, and therefore, are required to alter the patient’s

conditioned response.

These skills can be categorized into four modules: understanding and

naming emotions, changing unwanted emotions, reducing vulnerability, and

managing extreme conditions:

- Learning how to understand and name emotions: the patient focuses on recognizing their feelings. This segment relates directly to mindfulness, which also exposes a patient to their emotions.

- Changing unwanted emotions: the therapist emphasizes the use of opposite-reactions, fact-checking, and problem solving to regulate emotions. While using opposite-reactions, the patient targets distressing feelings by responding with the opposite emotion.

- Reducing vulnerability: the patient learns to accumulate positive emotions and to plan coping mechanisms in advance, in order to better handle difficult experiences in the future.

- Managing extreme conditions: the patient focuses on incorporating their use of mindfulness skills to their current emotions, in order to remain stable and alert in a crisis situation.

Story of emotion

This skill is used to understand what kind of emotion one is feeling.

- Prompting event

- Interpretation of the event

- Body sensations

- Body language

- Action urge

- Action

- Emotion name, based on previous items on list

PLEASE

This

skill concerns ineffective health habits that can make one more

vulnerable to emotion mind. This skill is used to maintain a healthy

body, so one is more likely to have healthy emotions.

- PhysicaL illness (treat) – If you are sick or injured, get proper treatment for it.

- Eating (balanced) – Make sure you eat a proper healthy diet, and eat in moderation.

- Avoid mood-altering drugs – Do not take other non-prescribed medication or drugs. They may be very harmful to your body, and can make your mood unpredictable.

- Sleep (balanced) – Do not sleep too much or too little. Eight hours of sleep is recommended per night for the average adult.

- Exercise – Make sure you get an effective amount of exercise, as this will both improve body image and release endorphins, making you happier.

Build mastery

- Try to do one thing a day to help build competence and control.

Opposite action

- This skill is used when you have an unjustified emotion, one that doesn't belong in the situation at hand. You use it by doing the opposite of your urges in the moment. It is a tool to bring you out of an unwanted or unjustified emotion by replacing it with the emotion that is opposite.

Problem solving

- This is used to solve a problem when your emotion is justified. It is used in combination with other skills.

Letting go of emotional suffering

- Observe and experience your emotion, accept it, then let it go.

Interpersonal effectiveness

Interpersonal

response patterns taught in DBT skills training are very similar to

those taught in many assertiveness and interpersonal problem-solving

classes. They include effective strategies for asking for what one

needs, saying no, and coping with interpersonal conflict.

Individuals with borderline personality disorder

frequently possess good interpersonal skills in a general sense. The

problems arise in the application of these skills to specific

situations. An individual may be able to describe effective behavioral

sequences when discussing another person encountering a problematic

situation, but may be completely incapable of generating or carrying out

a similar behavioral sequence when analyzing their own situation.

The interpersonal effectiveness module focuses on situations

where the objective is to change something (e.g., requesting that

someone do something) or to resist changes someone else is trying to

make (e.g., saying no). The skills taught are intended to maximize the

chances that a person's goals in a specific situation will be met, while

at the same time not damaging either the relationship or the person's

self-respect.

DEEAR MAN – conveying one's needs to another person

This acronym is used to aid one in getting what one wants when asking.

- Describe one's situation using specific factual statements about a recent situation.

- Express the emotions experienced when the situation occurred, why this is an issue and how one feels about it.

- Empathy acknowledge what the other person experienced and their emotions

- Assert one's self by asking clearly and specifically for what behavior change the person seeks.

- Reinforce one's position by offering a positive consequence if one were to get what one wants.

- Mindful of the situation by focusing on what one wants and disregard distractions through validation/empathy and redirecting back to the point.

- Appear confident and assertive, even if one doesn't feel confident.

- Negotiate with a hesitant person and come to a comfortable compromise on one's request.

GIVE – giving something

This skill set aids one maintaining one's relationships, whether they are with friends, co-workers, family, romantic partners, etc. It is to be used in conversations.

- Gentle: Use appropriate language, no verbal or physical attacks, no put downs, avoid sarcasm unless one is sure the person is alright with it, and be courteous and non-judgmental.

- Interested: When the person one is speaking to is talking about something, act interested in what is being said. Maintain eye contact, ask questions, etc. Avoid the use of a cell phone during an in-person conversation.

- Validate: Show understanding and sympathy of a person's situation. Validation can be shown through words, body language and/or facial expressions.

- Easy Manner: Be calm and comfortable during conversation; use humor; smile.

FAST – keeping self-respect

This is a skill to aid one in maintaining one's self-respect. It is to be used in combination with the other interpersonal effectiveness skills.

- Fair: Be fair to both oneself and the other person.

- Apologies (few): Don't apologize more than once for what one has done ineffectively or for something that was ineffective.

- Stick to One's Values: Stay true to what one believes in and stand by it. Don't allow others to encourage action against one's own values.

- Truthful: Don't lie. Lying can only pile up and damage relationships and one's self-respect.

This list does not include the "problem solving" module, the purpose of which is to practice being one's own therapist.

Tools

Diary cards

Specially formatted cards for tracking therapy interfering behaviors

that distract or hinder a patient's progress. Diary cards can be filled

out daily, 2–3 times a day, or once per week.

Chain analysis

Chain analysis is a form of functional analysis

of behavior but with increased focus on sequential events that form the

behavior chain. It has strong roots in behavioral psychology in

particular applied behavior analysis concept of chaining. A growing body of research supports the use of behavior chain analysis with multiple populations.

Milieu

The milieu, or the culture of the group involved, plays a key role in the effectiveness of DBT.

Efficacy

Borderline personality disorder

DBT

is the therapy that has been studied the most for treatment of

borderline personality disorder, and there have been enough studies done

to conclude that DBT is helpful in treating borderline personality

disorder.

A 2009 Canadian study compared the treatment of borderline personality

disorder with dialectical behavior therapy against general psychiatric

management. A total of 180 adults, 90 in each group, were admitted to

the study and treated for an average of 41 weeks. Statistically

significant decreases in suicidal events and non-suicidal self-injurious

events were seen overall (48% reduction, p=0.03; and 77% reduction,

p=0.01; respectively). No statistically-significant difference between

groups were seen for these episodes (p equal .64). Emergency department visits

decreased by 67% (p less than 0.0001) and emergency department visits for

suicidal behavior by 65% (p less than 0.0001), but there was also no

statistically significant difference between groups.

Depression

A

Duke University study of compared treatment of depression by

antidepressant medication to treatment by antidepressants and

dialectical behavior therapy. A total of 34 chronically depressed

individuals over age 60 were treated for 28 weeks. Six months after

treatment, statistically-significant differences were noted in remission

rates between groups, with a greater percentage of patients treated

with antidepressants and dialectical behavior therapy in remission.

Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Exposure to Complex trauma,

or the experience of traumatic events, can lead to the development of

Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) in an individual. CPTSD is a concept which divides the psychological community. The American Psychological Association (APA) does not recognize it in the DSM-5

(Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the manual

used by providers to diagnose, treat and discuss mental illness), though

some practitioners argue that CPTSD is separate from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder(PTSD).

CPTSD is similar to PTSD in that its symptomatology is pervasive and

includes cognitive, emotional, and biological domains, among others. CPTSD differs from PTSD in that it is believed to originate in childhood interpersonal trauma, or chronic childhood stress, and that the most common precedents are sexual traumas. Currently, the prevalence rate for CPTSD is an estimated .5%, while PTSD's is 1.5%. Numerous definitions for CPTSD exist. Different versions are contributed by the World Health Organization (WHO), The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS),

and individual clinicians and researchers. Most definitions revolve

around criteria for PTSD with the addition of several other domains.

While The APA may not recognize CPTSD, the WHO has recognized this

syndrome in its 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases

(ICD-11). The WHO defines CPTSD as a disorder following a single or

multiple events which cause the individual to feel stressed or trapped,

characterized by low self-esteem, interpersonal deficits, and deficits

in affect regulation. These deficits in affect regulation, among other symptoms are a reason why CPTSD is sometimes compared with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

Similarities Between CPTSD and Borderline Personality Disorder

In addition to affect dysregulation, case studies reveal that patients with CPTSD can also exhibit Splitting, mood swings, and fears of abandonment.

Like patients with Borderline Personality Disorder, patients with CPTSD

were traumatized frequently and/or early in their development and never

learned proper coping mechanisms. These individuals may use avoidance,

substances, dissociation, and other maladaptive behaviors to cope.

Thus, treatment for CPTSD involves stabilizing and teaching successful

coping behaviors, affect regulation, and creating and maintaining

interpersonal connections.

In addition to sharing symptom presentations, CPTSD and BPD can share

neurophysiological similarities. For example, abnormal volume of the amygdala (emotional memory), hippocampus (memory), anterior cingulate cortex (emotion), and orbital prefrontal cortex (personality). Another shared characteristic between CPTSD and BPD is the possibility for dissociation.

Further research is needed to determine the reliability of dissociation

as a hallmark of CPTSD, however it is a possible symptom.

Because of the two disorders’ shared symptomatology and physiological

correlates, psychologists began hypothesizing that a treatment which was

effective for one disorder may be effective for the other as well.

DBT as a Treatment for CPTSD

DBT’s

use of acceptance and goal orientation as an approach to behavior

change can help to instill empowerment and engage individuals in the

therapeutic process. The focus on the future and change can help to

prevent the individual from becoming from overwhelmed by their history

of trauma.

This is a risk especially with CPTSD, as multiple traumas are common

within this diagnosis. Generally, care providers address a client’s

suicidality before moving on to other aspects of treatment. Because PTSD

can make an individual more likely to experience suicidal ideation, DBT can be an option to stabilize suicidality and aid in other treatment modalities.

Some critics argue that while DBT can be used to treat CPTSD, it

is not significantly more effective than standard PTSD treatments.

Further, this argument posits that DBT decreases self-injurious

behaviors (such as cutting or burning) and increases interpersonal

functioning but neglects core CPTSD symptoms such as impulsivity, cognitive schemas (repetitive, negative thoughts), and emotions such as guilt and shame.

The ISTSS reports that CPTSD requires treatment which differs from

typical PTSD treatment, using a multiphase model of recovery, rather

than focusing on traumatic memories. The recommended multiphase model consists of establishing safety, distress tolerance, and social relations.

Because DBT has four modules which generally align with these

guidelines (Mindfulness, Distress Tolerance, Affect Regulation,

Interpersonal Skills) it is a treatment option. Other critiques of DBT

discuss the time required for the therapy to be effective.

Individuals seeking DBT may not be able to commit to the individual and

group sessions required, or their insurance may not cover every

session.

Approximately 56% of individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder also meet criteria for PTSD.

Because of the correlation between Borderline Personality Disorder

traits and trauma, some settings began using DBT as a treatment for

traumatic symptoms. Some providers opt to combine DBT with other PTSD interventions, such as Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE) (repeated, detailed description of the trauma in a psychotherapy session) or Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

(psychotherapy which addresses cognitive schemas related to traumatic

memories). For example, a regimen which combined PE and DBT would

include teaching mindfulness skills and distress tolerance skills, then

implementing PE. The individual with the disorder would then be taught

acceptance of a trauma's occurrence and how it may continue to affect

them throughout their lives. Participants

of clinical trials such as these exhibited a decrease in symptoms, and

throughout the 12-week trial, no self-injurious or suicidal behaviors

were reported.

Another argument which supports the use of DBT as a treatment for

trauma hinges upon PTSD symptoms such as emotion regulation and

distress. Some PTSD treatments such as exposure therapy may not be

suitable for individuals whose distress tolerance and/or emotion

regulation is low. Biosocial theory

posits that emotion dysregulation is caused by an individual’s

heightened emotional sensitivity combined with environmental factors

(such as invalidation of emotions, continued abuse/trauma), and tendency

to ruminate (repeatedly think about a negative event and how the outcome could have been changed). An individual who has these features is likely to use maladaptive coping behaviors.

DBT can be appropriate in these cases because it teaches appropriate

coping skills and allows the individuals to develop some degree of

self-sufficiency.

The first three modules of DBT increase distress tolerance and emotion

regulation skills in the individual, paving the way for work on symptoms

such as intrusions, self-esteem deficiency, and interpersonal

relations.

Noteworthy is that DBT has often been modified based on the

population being treated. For example, in veteran populations DBT is

modified to include exposure exercises and accommodate the presence of traumatic brain injury (TBI), and insurance coverage (ie shortening treatment). Populations with comorbid BPD may need to spend longer in the “Establishing Safety” phase.

In adolescent populations, the skills training aspect of DBT has

elicited significant improvement in emotion regulation and ability to

express emotion appropriately. In populations with comorbid substance abuse, adaptations may be made on a case-by-case basis. For example, a provider may wish to incorporate elements of Motivational Interviewing

(psychotherapy which uses empowerment to inspire behavior change). The

degree of substance abuse should also be considered. For some

individuals, substance use is the only coping behavior they know, and as

such the provider may seek to implement skills training before target

substance reduction. Inversely, a client’s substance abuse may be

interfering with attendance or other treatment compliance and the

provider may choose to address the substance use before implementing DBT

for the trauma.