General

"Nuclear winter," or as it was initially termed, "nuclear twilight," began to be considered as a scientific concept in the 1980s, after it became clear that an earlier hypothesis, that fireball generated NOx emissions would devastate the ozone layer,

was losing credibility. It was within this context that the climatic

effects of soot from fires was "chanced upon" and soon became the new

focus of the climatic effects of nuclear war. In these model scenarios, various soot clouds containing uncertain quantities of soot were assumed to form over cities, oil refineries, and more rural missile silos. Once the quantity of soot is decided upon by the researchers, the climate effects of these soot clouds are then modeled. The term "nuclear winter" was a neologism coined in 1983 by Richard P. Turco

in reference to a 1-dimensional computer model created to examine the

"nuclear twilight" idea, this 1-D model output the finding that massive

quantities of soot and smoke

would remain aloft in the air for on the order of years, causing a

severe planet-wide drop in temperature. Turco would later distance

himself from these extreme 1-D conclusions.

After the failure of the predictions on the effects of the 1991 Kuwait oil fires,

that were made by the primary team of climatologists that advocate the

hypothesis, over a decade passed without any new published papers on the

topic. More recently, the same team of prominent modellers from the

1980s have begun again to publish the outputs of computer models, these

newer models produce the same general findings as their old ones, that

the ignition of 100 firestorms, each comparable in intensity to that

observed in Hiroshima in 1945, could produce a "small" nuclear winter. These firestorms would result in the injection of soot (specifically black carbon) into the Earth's stratosphere, producing an anti-greenhouse effect that would lower the Earth's surface temperature. The severity of this cooling in Alan Robock's model suggests that the cumulative products of 100 of these firestorms could cool the global climate by approximately 1 °C (1.8 °F), largely eliminating the magnitude of anthropogenic global warming for two to three years. Robock has not modeled this, but has speculated that it would have global agricultural losses as a consequence.

As nuclear devices need not be detonated to ignite a firestorm, the term "nuclear winter" is something of a misnomer.

The majority of papers published on the subject state that without

qualitative justification, nuclear explosions are the cause of the

modeled firestorm effects. The only phenomenon that is modeled by

computer in the nuclear winter papers is the climate forcing agent of firestorm-soot, a product which can be ignited and formed by a myriad of means.

Although rarely discussed, the proponents of the hypothesis state that

the same "nuclear winter" effect would occur if 100 conventional

firestorms were ignited.

A much larger number of firestorms, in the thousands,

was the initial assumption of the computer modelers who coined the term

in the 1980s. These were speculated to be a possible result of any

large scale employment of counter-value airbursting nuclear weapon use during an American-Soviet total war. This larger number of firestorms, which are not in themselves modeled,

are presented as causing nuclear winter conditions as a result of the

smoke inputted into various climate models, with the depths of severe

cooling lasting for as long as a decade. During this period, summer

drops in average temperature could be up to 20 °C (36 °F) in core

agricultural regions of the US, Europe, and China, and as much as 35 °C

(63 °F) in Russia. This cooling would be produced due to a 99% reduction in the natural solar radiation reaching the surface of the planet in the first few years, gradually clearing over the course of several decades.

On the fundamental level, since the advent of photographic evidence of tall clouds were captured, it was known that firestorms could inject soot smoke/aerosols

into the stratosphere but the longevity of this slew of aerosols was a

major unknown. Independent of the team that continue to publish

theoretical models on nuclear winter, in 2006, Mike Fromm of the Naval Research Laboratory,

experimentally found that each natural occurrence of a massive wildfire

firestorm, much larger than that observed at Hiroshima, can produce

minor "nuclear winter" effects, with short-lived, approximately one

month of a nearly immeasurable drop in surface temperatures, confined to

the hemisphere that they burned in. This is somewhat analogous to the frequent volcanic eruptions that inject sulfates into the stratosphere and thereby produce minor, even negligible, volcanic winter effects.

A suite of satellite and aircraft-based firestorm-soot-monitoring

instruments are at the forefront of attempts to accurately determine

the lifespan, quantity, injection height, and optical properties of this smoke.

Information regarding all of these properties is necessary to truly

ascertain the length and severity of the cooling effect of firestorms,

independent of the nuclear winter computer model projections.

Presently, from satellite tracking data, stratospheric smoke aerosols dissipate in a time span under approximately two months. The existence of any hint of a tipping point into a new stratospheric condition where the aerosols would not be removed within this time frame remains to be determined.

Mechanism

Picture of a pyrocumulonimbus cloud

taken from a commercial airliner cruising at about 10 km. In 2002,

various sensing instruments detected 17 distinct pyrocumulonimbus cloud

events in North America alone.

The nuclear winter scenario assumes that 100 or more city firestorms are ignited by nuclear explosions, and that the firestorms lifts large amounts of sooty smoke into the upper troposphere

and lower stratosphere by the movement offered by the pyrocumulonimbus

clouds that form during a firestorm. At 10–15 kilometres (6–9 miles)

above the Earth's surface, the absorption of sunlight could further heat

the soot in the smoke, lifting some or all of it into the stratosphere,

where the smoke could persist for years if there is no rain to wash it

out. This aerosol of particles could heat the stratosphere and prevent a

portion of the sun's light from reaching the surface, causing surface

temperatures to drop drastically. In this scenario it is predicted that surface air temperatures would be the same as, or colder than, a given region's winter for months to years on end.

The modeled stable inversion layer

of hot soot between the troposphere and high stratosphere that produces

the anti-greenhouse effect was dubbed the "Smokeosphere" by Stephen Schneider et al. in their 1988 paper.

Although it is common in the climate models to consider city firestorms, these need not be ignited by nuclear devices;

more conventional ignition sources can instead be the spark of the

firestorms. Prior to the previously mentioned solar heating effect, the

soot's injection height is controlled by the rate of energy release from the firestorm's fuel, not the size of an initial nuclear explosion. For example, the mushroom cloud from the bomb dropped on Hiroshima

reached a height of six kilometers (middle troposphere) within a few

minutes and then dissipated due to winds, while the individual fires

within the city took almost three hours to form into a firestorm and

produce a pyrocumulus

cloud, a cloud that is assumed to have reached upper tropospheric

heights, as over its multiple hours of burning, the firestorm released

an estimated 1000 times the energy of the bomb.

As the incendiary effects of a nuclear explosion do not present any especially characteristic features, it is estimated by those with Strategic bombing experience that as the city was a firestorm hazard, the same fire ferocity and building damage produced at Hiroshima by one 16-kiloton nuclear bomb from a single B-29 bomber could have been produced instead by the conventional use of about 1.2 kilotons of incendiary bombs from 220 B-29s distributed over the city.

While the firestorms of Dresden and Hiroshima and the mass fires of Tokyo and Nagasaki occurred within mere months in 1945, the more intense and conventionally lit Hamburg firestorm

occurred in 1943. Despite the separation in time, ferocity and area

burned, leading modelers of the hypothesis state that these five fires

potentially placed five percent as much smoke into the stratosphere as

the hypothetical 100 nuclear-ignited fires discussed in modern models.

While it is believed that the modeled climate-cooling-effects from the

mass of soot injected into the stratosphere by 100 firestorms (one to

five teragrams) would have been detectable with technical instruments in

WWII, five percent of that would not have been possible to observe at

that time.

Aerosol removal timescale

Smoke rising in Lochcarron, Scotland, is stopped by an overlying natural low-level inversion layer of warmer air (2006).

The exact timescale for how long this smoke remains, and thus how

severely this smoke affects the climate once it reaches the

stratosphere, is dependent on both chemical and physical removal

processes.

The most important physical removal mechanism is "rainout", both during the "fire-driven convective column" phase, which produces "black rain" near the fire site, and rainout after the convective plume's dispersal, where the smoke is no longer concentrated and thus "wet removal" is believed to be very efficient. However, these efficient removal mechanisms in the troposphere are avoided in the Robock

2007 study, where solar heating is modeled to quickly loft the soot

into the stratosphere, "detraining" or separating the darker soot

particles from the fire clouds' whiter water condensation.

Once in the stratosphere, the physical removal mechanisms affecting the timescale of the soot particles' residence are how quickly the aerosol of soot collides and coagulates with other particles via Brownian motion, and falls out of the atmosphere via gravity-driven dry deposition, and the time it takes for the "phoretic effect" to move coagulated particles to a lower level in the atmosphere. Whether by coagulation or the phoretic effect, once the aerosol of smoke particles are at this lower atmospheric level, cloud seeding can begin, permitting precipitation to wash the smoke aerosol out of the atmosphere by the wet deposition mechanism.

The chemical processes that affect the removal are dependent on the ability of atmospheric chemistry to oxidize the carbonaceous component of the smoke, via reactions with oxidative species such as ozone and nitrogen oxides, both of which are found at all levels of the atmosphere, and which also occur at greater concentrations when air is heated to high temperatures.

Historical data on residence times of aerosols, albeit a different mixture of aerosols, in this case stratospheric sulfur aerosols and volcanic ash from megavolcano eruptions, appear to be in the one-to-two-year time scale, however aerosol–atmosphere interactions are still poorly understood.

Soot properties

Sooty aerosols can have a wide range of properties, as well as

complex shapes, making it difficult to determine their evolving

atmospheric optical depth

value. The conditions present during the creation of the soot are

believed to be considerably important as to their final properties, with

soot generated on the more efficient spectrum of burning efficiency considered almost "elemental carbon black," while on the more inefficient end of the burning spectrum, greater quantities of partially burnt/oxidized fuel are present. These partially burnt "organics" as they are known, often form tar balls and brown carbon during common lower-intensity wildfires, and can also coat the purer black carbon particles.

However, as the soot of greatest importance is that which is injected

to the highest altitudes by the pyroconvection of the firestorm – a fire

being fed with storm-force winds of air – it is estimated that the

majority of the soot under these conditions is the more oxidized black

carbon.

Consequences

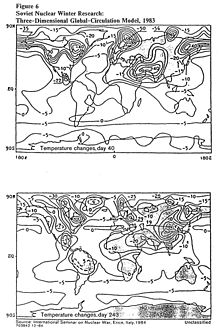

Diagram obtained by the CIA from the International Seminar on Nuclear War

in Italy 1984. It depicts the findings of Soviet 3-D computer model

research on nuclear winter from 1983, and although containing similar

errors as earlier Western models, it was the first 3-D model of nuclear

winter. (The three dimensions in the model are longitude, latitude and

altitude.)

The diagram shows the models predictions of global temperature changes

after a global nuclear exchange. The top image shows effects after 40

days, the bottom after 243 days. A co-author was nuclear winter

modelling pioneer Vladimir Alexandrov. Alexsandrov disappeared in 1985. As of 2016, there remains ongoing speculation by friend, Andrew Revkin, of foul play relating to his work.

Climatic effects

A study presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union

in December 2006 found that even a small-scale, regional nuclear war

could disrupt the global climate for a decade or more. In a regional

nuclear conflict scenario where two opposing nations in the subtropics would each use 50 Hiroshima-sized

nuclear weapons (about 15 kiloton each) on major population centers,

the researchers estimated as much as five million tons of soot would be

released, which would produce a cooling of several degrees over large

areas of North America and Eurasia, including most of the grain-growing

regions. The cooling would last for years, and, according to the

research, could be "catastrophic".

Ozone depletion

A 2008 study by Michael J. Mills et al., published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,

found that a nuclear weapons exchange between Pakistan and India using

their current arsenals could create a near-global ozone hole, triggering

human health problems and causing environmental damage for at least a

decade.

The computer-modeled study looked at a nuclear war between the two

countries involving 50 Hiroshima-sized nuclear devices on each side,

producing massive urban fires and lofting as much as five million metric

tons of soot about 50 miles (80 km) into the mesosphere. The soot would absorb enough solar radiation to heat surrounding gases, causing a series of surface chemistry reactions that would break down the stratospheric ozone layer protecting Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

Nuclear summer

A "nuclear summer" is a hypothesized scenario in which, after a nuclear winter has abated, a greenhouse effect then occurs due to carbon dioxide released by combustion and methane released from the decay of the organic matter that froze during the nuclear winter.

History

Early work

The mushroom cloud height as a function of explosive yield detonated as surface bursts. As charted, yields at least in the megaton range are required to lift dust/fallout into the stratosphere. Ozone reaches its maximum concentration at about 25 km (c. 82,000 ft) in altitude. Another means of stratospheric entry is from high altitude nuclear detonations, one example of which includes the 10.5 kiloton Soviet test no.#88 of 1961, detonated at 22.7 km. US high-yield upper atmospheric tests, Teak and Orange were also assessed for their ozone destruction potential. 0 = Approx altitude commercial aircraft operate.

In 1952, a few weeks prior to the Ivy Mike (10.4 megaton) bomb test on Elugelab island, there were concerns that the aerosols lifted by the explosion might cool the Earth. Major Norair Lulejian, USAF, and astronomer Natarajan Visvanathan, studied this possibility, reporting their findings in Effects of Superweapons Upon the Climate of the World. According to a document by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency",

this report was the initial study of the "nuclear winter" concept that

was popularized by others decades later. It indicated no appreciable

chance of explosion-induced climate change.

Following numerous surface bursts of high yield Hydrogen bomb explosions on Pacific Proving Ground islands such as those of Ivy Mike in 1952 and Castle Bravo (15 Mt) in 1954, The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Samuel Glasstone was published in 1957, containing a section entitled "Nuclear Bombs and the Weather", which states: "The dust raised in severe volcanic eruptions, such as that at Krakatoa

in 1883, is known to cause a noticeable reduction in the sunlight

reaching the earth … The amount of [soil or other surface] debris

remaining in the atmosphere after the explosion of even the largest

nuclear weapons is probably not more than about 1 percent or so of that

raised by the Krakatoa eruption. Further, solar radiation records reveal

that none of the nuclear explosions to date has resulted in any

detectable change in the direct sunlight recorded on the ground." The US Weather Bureau

in 1956 regarded it as conceivable that a large enough nuclear war with

megaton-range surface detonations could lift enough soil to cause a new

ice age.

In the 1966 RAND corporation memorandum The Effects of Nuclear War on the Weather and Climate by E. S. Batten, while primarily analysing potential dust effects from surface bursts,

it notes that "in addition to the effects of the debris, extensive

fires ignited by nuclear detonations might change the surface

characteristics of the area and modify local weather patterns ...

however, a more thorough knowledge of the atmosphere is necessary to

determine their exact nature, extent, and magnitude."

In the United States National Research Council (NRC) book Long-Term Worldwide Effects of Multiple Nuclear-Weapons Detonations published in 1975 it states that a nuclear war involving 4,000 Mt from present arsenals

would probably deposit much less dust in the stratosphere than the

Krakatoa eruption, judging that the effect of dust and oxides of

nitrogen would probably be slight climatic cooling which "would probably

lie within normal global climatic variability, but the possibility of

climatic changes of a more dramatic nature cannot be ruled out".

In the 1985 report The Effects on the Atmosphere of a Major Nuclear Exchange,

the Committee on the Atmospheric Effects of Nuclear Explosions argues

that a "plausible" estimate on the amount of stratospheric dust injected

following a surface burst of 1 Mt is 0.3 teragrams, of which 8 percent

would be in the micrometer range. The potential cooling from soil dust was again looked at in 1992, in a US National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report on geoengineering, which estimated that about 1010 kg (100 teragrams) of stratospheric injected soil dust with particulate grain dimensions of 0.1 to 1 micrometer would be required to mitigate the warming from a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, that is, to produce ~2 °C of cooling.

In 1969, Paul Crutzen discovered that oxides of nitrogen (NOx) could be an efficient catalyst for the destruction of the ozone layer/stratospheric ozone. Following studies on the potential effects of NOx generated by engine heat in stratosphere flying Supersonic Transport (SST) airplanes in the 1970s, in 1974, John Hampson suggested in the journal Nature that due to the creation of atmospheric NOx by nuclear fireballs,

a full-scale nuclear exchange could result in depletion of the ozone

shield, possibly subjecting the earth to ultraviolet radiation for a

year or more. In 1975, Hampson's hypothesis "led directly" to the United States National Research Council (NRC) reporting on the models of ozone depletion following nuclear war in the book Long-Term Worldwide Effects of Multiple Nuclear-Weapons Detonations.

In the section of this 1975 NRC book pertaining to the issue of

fireball generated NOx and ozone layer loss therefrom, the NRC present

model calculations from the early-to-mid 1970s on the effects of a

nuclear war with the use of large numbers of multi-megaton yield

detonations, which returned conclusions that this could reduce ozone

levels by 50 percent or more in the northern hemisphere.

However independent of the computer models presented in the 1975 NRC works, a paper in 1973 in the journal Nature

depicts the stratospheric ozone levels worldwide overlaid upon the

number of nuclear detonations during the era of atmospheric testing. The

authors conclude that neither the data nor their models show any

correlation between the approximate 500 Mt in historical atmospheric

testing and an increase or decrease of ozone concentration.

In 1976, a study on the experimental measurements of an earlier

atmospheric nuclear test as it affected the ozone layer also found that

nuclear detonations are exonerated of depleting ozone, after the at

first alarming model calculations of the time.

Similarly, a 1981 paper found that the models on ozone destruction from

one test and the physical measurements taken were in disagreement, as

no destruction was observed.

In total about 500 Mt were atmospherically detonated between 1945 and 1971, peaking in 1961–62, when 340 Mt were detonated in the atmosphere by the United States and Soviet Union.

During this peak, with the multi-megaton range detonations of the two

nations nuclear test series, in exclusive examination, a total yield

estimated at 300 Mt of energy was released. Due to this, 3 × 1034 additional molecules of nitric oxide (about 5,000 tons per Mt, 5 × 109 grams per megaton)

are believed to have entered the stratosphere, and while ozone

depletion of 2.2 percent was noted in 1963, the decline had started

prior to 1961 and is believed to have been caused by other meteorological effects.

In 1982 journalist Jonathan Schell in his popular and influential book The Fate of the Earth,

introduced the public to the belief that fireball generated NOx would

destroy the ozone layer to such an extent that crops would fail from

solar UV radiation and then similarly painted the fate of the Earth, as

plant and aquatic life going extinct. In the same year, of 1982,

Australian physicist Brian Martin, who frequently corresponded with John Hampson who had been greatly responsible for much of the examination of NOx generation,

penned a short historical synopsis on the history of interest in the

effects of the direct NOx generated by nuclear fireballs, and in doing

so, also outlined Hampson's other non-mainstream viewpoints,

particularly those relating to greater ozone destruction from

upper-atmospheric detonations as a result of any widely used anti-ballistic missile (ABM-1 Galosh) system.

However, Martin ultimately concludes that it is "unlikely that in the

context of a major nuclear war" ozone degradation would be of serious

concern. Martin describes views about potential ozone loss and therefore

increases in ultraviolet light leading to the widespread destruction of crops, as advocated by journalist Jonathan Schell inThe Fate of the Earth, as highly unlikely.

More recent accounts on the specific ozone layer destruction

potential of NOx species are much less than earlier assumed from

simplistic calculations, as "about 1.2 million tons" of natural and anthropogenic generated stratospheric NOx is believed to be formed each year according to Robert P. Parson in the 1990s.

Science fiction

The

first published suggestion that a cooling of climate could be an effect

of a nuclear war, appears to have been originally put forth by Poul Anderson and F.N. Waldrop in their post-war story "Tomorrow's Children", in the March 1947 issue of the Astounding Science Fiction magazine. The story, primarily about a team of scientists hunting down mutants, warns of a "Fimbulwinter" caused by dust that blocked sunlight after a recent nuclear war and speculated that it may even trigger a new Ice Age. Anderson went on to publish a novel based partly on this story in 1961 titling it Twilight World. Similarly in 1985 it was noted by T. G. Parsons that the story Torch by C. Anvil, which also appeared in Astounding Science Fiction

magazine, but in the April 1957 edition, contains the essence of the

"Twilight at Noon"/"nuclear winter" hypothesis. In the story a nuclear

warhead ignites an oil field, and the soot produced "screens out part of

the sun's radiation", resulting in Arctic temperatures for much of the

population of North America and the Soviet Union.

1980s

The 1988 Air Force Geophysics Laboratory publication An assessment of global atmospheric effects of a major nuclear war

by H. S. Muench et al. contains a chronology and review of the major

reports on the nuclear winter hypothesis from 1983–86. In general these

reports arrive at similar conclusions as they are based on "the same

assumptions, the same basic data", with only minor model-code

differences. They skip the modeling steps of assessing the possibility

of fire and the initial fire plumes and instead start the modeling

process with a "spatially uniform soot cloud" which has found its way

into the atmosphere.

Although never openly acknowledged by the multi-disciplinary team who authored the most popular 1980s TTAPS model, in 2011 the American Institute of Physics

states that the TTAPS team (named for its participants, who had all

previously worked on the phenomenon of dust storms on Mars, or in the

area of asteroid impact events: Richard P. Turco, Owen Toon, Thomas P. Ackerman, James B. Pollack and Carl Sagan) announcement of their results in 1983 "was with the explicit aim of promoting international arms control".

However, "the computer models were so simplified, and the data on smoke

and other aerosols were still so poor, that the scientists could say

nothing for certain."

In 1981, William J. Moran began discussions and research in the National Research Council

(NRC) on the airborne soil/dust effects of a large exchange of nuclear

warheads, having seen a possible parallel in the dust effects of a war

with that of the asteroid-created K-T boundary and its popular analysis a year earlier by Luis Alvarez in 1980. An NRC study panel on the topic met in December 1981 and April 1982 in preparation for the release of the NRC's The Effects on the Atmosphere of a Major Nuclear Exchange, published in 1985.

As part of a study on the creation of oxidizing species such as NOx and ozone in the troposphere after a nuclear war, launched in 1980 by AMBIO, a journal of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Paul J. Crutzen

and John Birks began preparing for the 1982 publication of a

calculation on the effects of nuclear war on stratospheric ozone, using

the latest models of the time. However they found that in part as a

result of the trend towards more numerous but less energetic,

sub-megaton range nuclear warheads (made possible by the ceaseless march

to increase ICBM warhead accuracy/Circular Error Probable), the ozone layer danger was "not very significant".

It was after being confronted with these results that they "chanced" upon the notion, as "an afterthought"

of nuclear detonations igniting massive fires everywhere and,

crucially, the smoke from these conventional fires then going on to

absorb sunlight, causing surface temperatures to plummet.

In early 1982, the two circulated a draft paper with the first

suggestions of alterations in short-term climate from fires presumed to

occur following a nuclear war. Later in the same year, the special issue of Ambio

devoted to the possible environmental consequences of nuclear war by

Crutzen and Birks was titled "Twilight at Noon", and largely anticipated

the nuclear winter hypothesis.

The paper looked into fires and their climatic effect and discussed

particulate matter from large fires, nitrogen oxide, ozone depletion and

the effect of nuclear twilight on agriculture. Crutzen and Birks'

calculations suggested that smoke particulates injected into the

atmosphere by fires in cities, forests and petroleum reserves could

prevent up to 99% of sunlight from reaching the Earth's surface. This

darkness, they said, could exist "for as long as the fires burned",

which was assumed to be many weeks, with effects such as: "The normal

dynamic and temperature structure of the atmosphere would ... change

considerably over a large fraction of the Northern Hemisphere, which

will probably lead to important changes in land surface temperatures and

wind systems." An implication of their work was that a successful nuclear decapitation strike could have severe climatic consequences for the perpetrator.

After reading a paper by N. P. Bochkov and E. I. Chazov, published in the same edition of Ambio that carried Crutzen and Birks's paper "Twilight at Noon", Soviet atmospheric scientist Georgy Golitsyn applied his research on Mars dust storms

to soot in the Earth's atmosphere. The use of these influential Martian

dust storm models in nuclear winter research began in 1971, when the Soviet spacecraft Mars 2 arrived at the red planet and observed a global dust cloud. The orbiting instruments together with the 1971 Mars 3

lander determined that temperatures on the surface of the red-planet

were considerably colder than temperatures at the top of the dust cloud.

Following these observations, Golitsyn received two telegrams from

astronomer Carl Sagan,

in which Sagan asked Golitsyn to "explore the understanding and

assessment of this phenomenon." Golitsyn recounts that it was around

this time that he had "proposed a theory to explain how Martian dust may be formed and how it may reach global proportions."

In the same year Alexander Ginzburg,

an employee in Golitsyn's institute, developed a model of dust storms

to describe the cooling phenomenon on Mars. Golitsyn felt that his model

would be applicable to soot after he read a 1982 Swedish magazine

dedicated to the effects of a hypothetical nuclear war between the USSR

and the US.

Golitsyn would use Ginzburg's largely unmodified dust-cloud model with

soot assumed as the aerosol in the model instead of soil dust and in an

identical fashion to the results returned, when computing dust-cloud

cooling in the Martian atmosphere, the cloud high above the planet would

be heated while the planet below would cool drastically. Golitsyn

presented his intent to publish this Martian derived Earth-analog model

to the Andropov instigated Committee of Soviet Scientists in Defence of Peace Against the Nuclear Threat in May 1983, an organization that Golitsyn would later be appointed a position of vice-chairman of.

The establishment of this committee was done with the expressed

approval of the Soviet leadership with the intent "to expand controlled

contacts with Western "nuclear freeze" activists".

Having gained this committees approval, in September 1983, Golitsyn

published the first computer model on the nascent "nuclear winter"

effect in the widely read Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

On 31 October 1982, Golitsyn and Ginsburg's model and results

were presented at the conference on "The World after Nuclear War",

hosted in Washington, D.C.

Both Golitsyn and Sagan

had been interested in the cooling on the dust storms on the planet

Mars in the years preceding their focus on "nuclear winter". Sagan had

also worked on Project A119 in the 1950s–60s, in which he attempted to model the movement and longevity of a plume of lunar soil.

After the publication of "Twilight at Noon" in 1982,

the TTAPS team have said that they began the process of doing a

1-dimensional computational modeling study of the atmospheric

consequences of nuclear war/soot in the stratosphere, though they would

not publish a paper in Science magazine until late December 1983. The phrase "nuclear winter" had been coined by Turco just prior to publication.

In this early paper, TTAPS used assumption based estimates on the total

smoke and dust emissions that would result from a major nuclear

exchange, and with that, began analyzing the subsequent effects on the

atmospheric radiation balance

and temperature structure as a result of this quantity of assumed

smoke. To compute dust and smoke effects, they employed a

one-dimensional microphysics/radiative-transfer model of the Earth's

lower atmosphere (up to the mesopause), which defined only the vertical

characteristics of the global climate perturbation.

Interest in the environmental effects of nuclear war, however,

had continued in the Soviet Union after Golitsyn's September paper, with

Vladimir Alexandrov

and G. I. Stenchikov also publishing a paper in December 1983 on the

climatic consequences, although in contrast to the contemporary TTAPS

paper, this paper was based on simulations with a three-dimensional

global circulation model.

(Two years later Alexandrov disappeared under mysterious

circumstances). Richard Turco and Starley L. Thompson were both critical

of the Soviet research. Turco called it "primitive" and Thompson said

it used obsolete US computer models.

Later they were to rescind these criticisms and instead applauded

Alexandrov's pioneering work, saying that the Soviet model shared the

weaknesses of all the others.

In 1984, the World Meteorological Organization

(WMO) commissioned Golitsyn and N. A. Phillips to review the state of

the science. They found that studies generally assumed a scenario where

half of the world's nuclear weapons would be used, ~5000 Mt, destroying

approximately 1,000 cities, and creating large quantities of

carbonaceous smoke – 1–2×1014 g being most likely, with a range of 0.2–6.4×1014 g (NAS; TTAPS assumed 2.25×1014).

The smoke resulting would be largely opaque to solar radiation but

transparent to infrared, thus cooling the Earth by blocking sunlight,

but not creating warming by enhancing the greenhouse effect. The optical

depth of the smoke can be much greater than unity. Forest fires

resulting from non-urban targets could increase aerosol production

further. Dust from near-surface explosions against hardened targets also

contributes; each megaton-equivalent explosion could release up to 5

million tons of dust, but most would quickly fall out; high altitude

dust is estimated at 0.1–1 million tons per megaton-equivalent of

explosion. Burning of crude oil could also contribute substantially.

The 1-D radiative-convective models used in these

studies produced a range of results, with coolings up to 15–42 °C

between 14 and 35 days after the war, with a "baseline" of about 20 °C.

Somewhat more sophisticated calculations using 3-D GCMs produced similar results: temperature drops of about 20 °C, though with regional variations.

All

calculations show large heating (up to 80 °C) at the top of the smoke

layer at about 10 km (6.2 mi); this implies a substantial modification

of the circulation there and the possibility of advection of the cloud

into low latitudes and the southern hemisphere.

1990

In a 1990

paper entitled "Climate and Smoke: An Appraisal of Nuclear Winter",

TTAPS gave a more detailed description of the short- and long-term

atmospheric effects of a nuclear war using a three-dimensional model:

First 1 to 3 months:

- 10 to 25% of soot injected is immediately removed by precipitation, while the rest is transported over the globe in 1 to 2 weeks

- SCOPE figures for July smoke injection:

- 22 °C drop in mid-latitudes

- 10 °C drop in humid climates

- 75% decrease in rainfall in mid-latitudes

- Light level reduction of 0% in low latitudes to 90% in high smoke injection areas

- SCOPE figures for winter smoke injection:

- Temperature drops between 3 and 4 °C

Following 1 to 3 years:

- 25 to 40% of injected smoke is stabilised in atmosphere (NCAR). Smoke stabilised for approximately 1 year.

- Land temperatures of several degrees below normal

- Ocean surface temperature between 2 and 6 °C

- Ozone depletion of 50% leading to 200% increase in UV radiation incident on surface.

Kuwait wells in the first Gulf War

The Kuwaiti oil fires were not just limited to burning oil wells,

one of which is seen here in the background, but burning "oil lakes",

seen in the foreground, also contributed to the smoke plumes,

particularly the sootiest/blackest of them.

Smoke plumes from a few of the Kuwaiti Oil Fires

on April 7, 1991. The maximum assumed extent of the combined plumes

from over six hundred fires during the period of February 15 – May 30,

1991, are available.

Only about 10% of all the fires, mostly corresponding with those that

originated from "oil lakes" produced pure black soot filled plumes, 25%

of the fires emitted white to grey plumes, while the remaining emitted

plumes with colors between grey and black.

One of the major results of TTAPS' 1990 paper was the re-iteration of the team's 1983 model that 100 oil refinery fires would be sufficient to bring about a small scale, but still globally deleterious nuclear winter.

Following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait

and Iraqi threats of igniting the country's approximately 800 oil

wells, speculation on the cumulative climatic effect of this, presented

at the World Climate Conference in Geneva that November in 1990, ranged from a nuclear winter type scenario, to heavy acid rain and even short term immediate global warming.

In articles printed in the Wilmington Morning Star and the Baltimore Sun

newspapers in January 1991, prominent authors of nuclear winter papers –

Richard P. Turco, John W. Birks, Carl Sagan, Alan Robock and Paul

Crutzen – collectively stated that they expected catastrophic nuclear

winter like effects with continental-sized effects of sub-freezing

temperatures as a result of the Iraqis going through with their threats

of igniting 300 to 500 pressurized oil wells that could subsequently

burn for several months.

As threatened, the wells were set on fire

by the retreating Iraqis in March 1991, and the 600 or so burning oil

wells were not fully extinguished until November 6, 1991, eight months

after the end of the war, and they consumed an estimated six million barrels of oil per day at their peak intensity.

When Operation Desert Storm begun in January 1991, coinciding with the first few oil fires being lit, Dr. S. Fred Singer and Carl Sagan discussed the possible environmental effects of the Kuwaiti petroleum fires on the ABC News program Nightline.

Sagan again argued that some of the effects of the smoke could be

similar to the effects of a nuclear winter, with smoke lofting into the

stratosphere, beginning around 48,000 feet (15,000 m) above sea level in

Kuwait, resulting in global effects. He also argued that he believed

the net effects would be very similar to the explosion of the Indonesian

volcano Tambora in 1815, which resulted in the year 1816 being known as the Year Without a Summer.

Sagan listed modeling outcomes that forecast effects extending to South Asia,

and perhaps to the Northern Hemisphere as well. Sagan stressed this

outcome was so likely that "It should affect the war plans."

Singer, on the other hand, anticipated that the smoke would go to an

altitude of about 3,000 feet (910 m) and then be rained out after about

three to five days, thus limiting the lifetime of the smoke. Both height

estimates made by Singer and Sagan turned out to be wrong, albeit with

Singer's narrative being closer to what transpired, with the

comparatively minimal atmospheric effects remaining limited to the

Persian Gulf region, with smoke plumes, in general, lofting to about 10,000 feet (3,000 m) and a few as high as 20,000 feet (6,100 m).

Sagan and his colleagues expected that a "self-lofting" of the

sooty smoke would occur when it absorbed the sun's heat radiation, with

little to no scavenging occurring, whereby the black particles of soot

would be heated by the sun and lifted/lofted higher and higher into the

air, thereby injecting the soot into the stratosphere, a position where

they argued it would take years for the sun blocking effect of this

aerosol of soot to fall out of the air, and with that, catastrophic

ground level cooling and agricultural effects in Asia and possibly the

Northern Hemisphere as a whole. In a 1992 follow-up, Peter Hobbs

and others had observed no appreciable evidence for the nuclear winter

team's predicted massive "self-lofting" effect and the oil-fire smoke

clouds contained less soot than the nuclear winter modelling team had

assumed.

The atmospheric scientist tasked with studying the atmospheric effect of the Kuwaiti fires by the National Science Foundation, Peter Hobbs,

stated that the fires' modest impact suggested that "some numbers [used

to support the Nuclear Winter hypothesis]... were probably a little

overblown."

Hobbs found that at the peak of the fires, the smoke absorbed 75

to 80% of the sun's radiation. The particles rose to a maximum of

20,000 feet (6,100 m), and when combined with scavenging by clouds the

smoke had a short residency time of a maximum of a few days in the

atmosphere.

Pre-War claims of wide scale, long-lasting, and significant global

environmental effects were thus not borne out, and found to be

significantly exaggerated by the media and speculators,

with climate models by those not supporting the nuclear winter

hypothesis at the time of the fires predicting only more localized

effects such as a daytime temperature drop of ~10 °C within 200 km of

the source.

This satellite photo of the south of Britain shows black smoke from the 2005 Buncefield fire, a series of fires and explosions involving approximately 250,000,000 litres

of fossil fuels. The plume is seen spreading in two main streams from

the explosion site at the apex of the inverted 'v'. By the time the fire

had been extinguished the smoke had reached the English Channel.

The orange dot is a marker, not the actual fire. Although the smoke

plume was from a single source, and larger in size than the individual oil well fire plumes in Kuwait 1991, the Buncefield smoke cloud remained out of the stratosphere.

Sagan later conceded in his book The Demon-Haunted World that his predictions obviously did not turn out to be correct: "it was

pitch black at noon and temperatures dropped 4–6 °C over the Persian

Gulf, but not much smoke reached stratospheric altitudes and Asia was

spared."

The idea of oil well and oil reserve smoke pluming into the

stratosphere serving as a main contributor to the soot of a nuclear

winter was a central idea of the early climatology papers on the

hypothesis; they were considered more of a possible contributor than

smoke from cities, as the smoke from oil has a higher ratio of black

soot, thus absorbing more sunlight.

Hobbs compared the papers' assumed "emission factor" or soot generating

efficiency from ignited oil pools and found, upon comparing to measured

values from oil pools at Kuwait, which were the greatest soot

producers, the emissions of soot assumed in the nuclear winter

calculations were still "too high".

Following the results of the Kuwaiti oil fires being in disagreement

with the core nuclear winter promoting scientists, 1990s nuclear winter

papers generally attempted to distance themselves from suggesting oil

well and reserve smoke will reach the stratosphere.

In 2007, a nuclear winter study, noted that modern computer

models have been applied to the Kuwait oil fires, finding that

individual smoke plumes are not able to loft smoke into the

stratosphere, but that smoke from fires covering a large area like some forest fires can lift smoke into the stratosphere, and recent evidence suggests that this occurs far more often than previously thought.

The study also suggested that the burning of the comparably smaller

cities, which would be expected to follow a nuclear strike, would also

loft significant amounts of smoke into the stratosphere:

Stenchikov et al. [2006b] conducted detailed, high-resolution smoke plume simulations with the RAMS regional climate model [e.g., Miguez-Macho et al., 2005] and showed that individual plumes, such as those from the Kuwait oil fires in 1991, would not be expected to loft into the upper atmosphere or stratosphere, because they become diluted. However, much larger plumes, such as would be generated by city fires, produce large, undiluted mass motion that results in smoke lofting. New large eddy simulation model results at much higher resolution also give similar lofting to our results, and no small scale response that would inhibit the lofting [Jensen, 2006].

However the above simulation notably contained the assumption that no dry or wet deposition would occur.

Recent modeling

Between 1990 and 2003, commentators noted that no peer-reviewed papers on "nuclear winter" were published.

Based on new work published in 2007 and 2008 by some of the

authors of the original studies, several new hypotheses have been put

forth, primarily the assessment that as few as 100 firestorms would

result in a nuclear winter.

However far from the hypothesis being "new", it drew the same

conclusion as earlier 1980s models, which similarly regarded 100 or so

city firestorms as a threat.

A minor nuclear war with each country using 50 Hiroshima-sized

atom bombs as air-bursts on urban areas could produce climate change

unprecedented in recorded human history. A nuclear war between the

United States and Russia today could produce nuclear winter, with

temperatures plunging below freezing in the summer in major agricultural

regions, threatening the food supply for most of the planet. The

climatic effects of the smoke from burning cities and industrial areas

would last for several years, much longer than previously thought. New

climate model simulations, which are said to have the capability of

including the entire atmosphere and oceans, show that the smoke would be

lofted by solar heating to the upper stratosphere, where it would

remain for years.

Compared to climate change for the past millennium, even the

smallest exchange modeled would plunge the planet into temperatures

colder than the Little Ice Age

(the period of history between approximately 1600 and 1850 AD). This

would take effect instantly, and agriculture would be severely

threatened. Larger amounts of smoke would produce larger climate

changes, and for the 150 teragrams (Tg) producing a true nuclear winter

(1 Tg is 1012 grams), making agriculture impossible for

years. In both cases, new climate model simulations show that the

effects would last for more than a decade.

2007 study on global nuclear war

A study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in July 2007, titled "Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences",

used current climate models to look at the consequences of a global

nuclear war involving most or all of the world's current nuclear

arsenals (which the authors judged to be one similar to the size of the

world's arsenals twenty years earlier). The authors used a global

circulation model, ModelE from the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies,

which they noted "has been tested extensively in global warming

experiments and to examine the effects of volcanic eruptions on

climate." The model was used to investigate the effects of a war

involving the entire current global nuclear arsenal, projected to

release about 150 Tg of smoke into the atmosphere, as well as a war

involving about one third of the current nuclear arsenal, projected to

release about 50 Tg of smoke. In the 150 Tg case they found that:

A global average surface cooling of −7 °C to −8 °C persists for years, and after a decade the cooling is still −4 °C (Fig. 2). Considering that the global average cooling at the depth of the last ice age 18,000 yr ago was about −5 °C, this would be a climate change unprecedented in speed and amplitude in the history of the human race. The temperature changes are largest over land … Cooling of more than −20 °C occurs over large areas of North America and of more than −30 °C over much of Eurasia, including all agricultural regions.

In addition, they found that this cooling caused a weakening of the

global hydrological cycle, reducing global precipitation by about 45%.

As for the 50 Tg case involving one third of current nuclear arsenals,

they said that the simulation "produced climate responses very similar

to those for the 150 Tg case, but with about half the amplitude," but

that "the time scale of response is about the same." They did not

discuss the implications for agriculture in depth, but noted that a 1986

study which assumed no food production for a year projected that "most

of the people on the planet would run out of food and starve to death by

then" and commented that their own results show that, "This period of

no food production needs to be extended by many years, making the

impacts of nuclear winter even worse than previously thought."

2014

In 2014, Michael J. Mills (at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research,

NCAR) et al. published "Multi-decadal global cooling and unprecedented

ozone loss following a regional nuclear conflict" in the journal Earth's Future.

The authors used computational models developed by NCAR to simulate the

climatic effects of a soot cloud that they suggest would be a result,

of a regional nuclear war in which 100 "small" (15 Kt) weapons are

detonated over cities. The model had outputs, due to the interaction of

the soot cloud:

...global ozone losses of 20–50% over populated areas, levels unprecedented in human history, would accompany the coldest average surface temperatures in the last 1000 years. We calculate summer enhancements in UV indices of 30–80% over Mid-Latitudes, suggesting widespread damage to human health, agriculture, and terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Killing frosts would reduce growing seasons by 10–40 days per year for 5 years. Surface temperatures would be reduced for more than 25 years, due to thermal inertia and albedo effects in the ocean and expanded sea ice. The combined cooling and enhanced UV would put significant pressures on global food supplies and could trigger a global nuclear famine.

2018

Research published in the peer-reviewed journal Safety

suggested that no nation should possess more than 100 nuclear warheads

because of the blowback effect on the aggressor nation's own population

because of "nuclear autumn".

Criticism and debate

The

four major, largely independent underpinnings that the nuclear winter

concept has and continues to receive criticism over, are regarded as: firstly, would cities readily firestorm, and if so how much soot would be generated. Secondly, atmospheric

longevity; would the quantities of soot assumed in the models remain in

the atmosphere for as long as projected or would far more soot

precipitate as black rain much sooner. Third, timing

of events; how realistic is it to start the firestorms or war modelling

in late spring or summer, which almost all US-Soviet winter papers

assume, so as to depict the maximum possible cooling results. Lastly,

the issue of darkness or opacity; how much light-blocking effect the assumed quality of the soot reaching the atmosphere would have.

While the highly popularized initial 1983 TTAPS 1-dimensional

model forecasts were widely reported and criticized in the media, in

part because every later model predicts far less of its "apocalyptic"

level of cooling,

most models continue to suggest that some deleterious global cooling

would still result, under the assumption that a large number of fires

occurred in the spring or summer. Starley L. Thompson's less primitive mid-1980s 3-Dimensional

model, which notably contained the very same general assumptions, led

him to coin the term "nuclear autumn" to more accurately describe the

climate results of the soot in this model, in an on camera interview in

which he dismisses the earlier "apocalyptic" models.

A major criticism of the assumptions that continue to make these model results possible appeared in the 1987 book Nuclear War Survival Skills (NWSS), a civil defense manual by Cresson Kearny for the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. According to the 1988 publication An assessment of global atmospheric effects of a major nuclear war,

Kearny's criticisms were directed at the excessive amount of soot that

the modelers assumed would reach the stratosphere. Kearny cited a Soviet

study that modern cities would not burn as firestorms, as most

flammable city items would be buried under non-combustible rubble and

that the TTAPS study included a massive overestimate on the size and

extent of non-urban wildfires that would result from a nuclear war.

The TTAPS authors responded that, among other things, they did not

believe target planners would intentionally blast cities into rubble,

but instead argued fires would begin in relatively undamaged suburbs

when nearby sites were hit, and partially conceded his point about

non-urban wildfires.

Dr. Richard D. Small, director of thermal sciences at the

Pacific-Sierra Research Corporation similarly disagreed strongly with

the model assumptions, in particular the 1990 update by TTAPS that

argues that some 5,075 Tg of material would burn in a total US-Soviet

nuclear war, as analysis by Small of blueprints and real buildings

returned a maximum of 1,475 Tg of material that could be burned,

"assuming that all the available combustible material was actually

ignited".

Although Kearny was of the opinion that future more accurate

models would "indicate there will be even smaller reductions in

temperature", including future potential models that did not so readily

accept that firestorms would occur as dependably as nuclear winter

modellers assume, in NWSS Kearny did summarize the comparatively moderate cooling estimate of no more than a few days, from the 1986 Nuclear Winter Reappraised model by Starley Thompson and Stephen Schneider.

This was done in an effort to convey to his readers that contrary to

the popular opinion at the time, in the conclusion of these two climate

scientists, "on scientific grounds the global apocalyptic conclusions of

the initial nuclear winter hypothesis can now be relegated to a

vanishing low level of probability."

However while a 1988 article by Brian Martin in Science and Public Policy states that although Nuclear Winter Reappraised

concluded the US-Soviet "nuclear winter" would be much less severe than

originally thought, with the authors describing the effects more as a

"nuclear autumn", other statements by Thompson and Schneider

show that they "resisted the interpretation that this means a rejection

of the basic points made about nuclear winter". In the Alan Robock et

al. 2007 paper they write that "because of the use of the term 'nuclear

autumn' by Thompson and Schneider [1986], even though the authors made

clear that the climatic consequences would be large, in policy circles

the theory of nuclear winter is considered by some to have been

exaggerated and disproved [e.g., Martin, 1988]."

In 2007 Schneider expressed his tentative support for the cooling

results of the limited nuclear war (Pakistan and India) analyzed in the

2006 model, saying "The sun is much stronger in the tropics than it is

in mid-latitudes. Therefore, a much more limited war [there] could have a

much larger effect, because you are putting the smoke in the worst

possible place", and "anything that you can do to discourage people from

thinking that there is any way to win anything with a nuclear exchange

is a good idea."

The contribution of smoke from the ignition of live non-desert vegetation, living forests, grasses and so on, nearby to many missile silos

is a source of smoke originally assumed to be very large in the initial

"Twilight at Noon" paper, and also found in the popular TTAPS

publication. However, this assumption was examined by Bush and Small in

1987 and they found that the burning of live vegetation could only

conceivably contribute very slightly to the estimated total "nonurban

smoke production". With the vegetation's potential to sustain burning only probable if it is within a radius or two from the surface of the nuclear fireball, which is at a distance that would also experience extreme blast winds that would influence any such fires. This reduction in the estimate of the non-urban smoke hazard is supported by the earlier preliminary Estimating Nuclear Forest Fires publication of 1984, and by the 1950–60s in-field examination of surface-scorched, mangled but never burnt-down tropical forests on the surrounding islands from the shot points in the Operation Castle, and Operation Redwing test series.

During the Operation Meeting House firebombing of Tokyo on 9–10 March 1945, 1,665 tons(1.66 kilotons) of incendiary and high-explosive bombs in the form of bomblets were dropped on the city, causing the destruction of over 10,000 acres of buildings – 16 square miles (41 km2), the most destructive and deadliest bombing operation in history.

The first nuclear bombing in history used a 16-kiloton nuclear bomb, approximately 10 times more energy than delivered onto Tokyo, yet due in part to the comparative inefficiency of larger bombs,[note 1][157] a much smaller area of building destruction occurred when contrasted with the results from Tokyo. Only 4.5 square miles (12 km2) of Hiroshima was destroyed by blast, fire, and firestorm effects. Similarly, Major Cortez F. Enloe, a surgeon in the USAAF who worked with the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), noted that the even more energetic 22-kiloton nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki did not result in a firestorm and thus did not do as much fire damage as the conventional airstrikes on Hamburg which did generate a firestorm.

Thus, the question of can a city firestorm; has nothing to do with the

size or type of bomb dropped, but solely depends on the density of fuel

present in the city. Moreover, it has been observed that firestorms are

not likely in areas where modern buildings (constructed of bricks and

concrete) have totally collapsed. By comparison, Hiroshima, and Japanese

cities in general in 1945, had consisted of mostly densely-packed

wooden houses along with the common use of Shoji paper sliding walls.

The fire hazard construction practices present in cities that have

historically firestormed, are now illegal in most countries for general

safety reasons and therefore cities with firestorm potential are far

rarer than was common at the time of WWII.

A paper by the United States Department of Homeland Security,

finalized in 2010, states that after a nuclear detonation targeting a

city "If fires are able to grow and coalesce, a firestorm could develop

that would be beyond the abilities of firefighters to control. However

experts suggest in the nature of modern US city design and construction

may make a raging firestorm unlikely". The nuclear bombing of Nagasaki for example, did not produce a firestorm.

This was similarly noted as early as 1986–88, when the assumed quantity

of fuel "mass loading" (the amount of fuel per square meter) in cities

underpinning the winter models was found to be too high and

intentionally creates heat fluxes

that loft smoke into the lower stratosphere, yet assessments "more

characteristic of conditions" to be found in real-world modern cities,

had found that the fuel loading, and hence the heat flux that would

result from efficient burning, would rarely loft smoke much higher than

4 km.

Russell Seitz, Associate of the Harvard University Center for

International Affairs, argues that the winter models' assumptions give

results which the researchers want to achieve and is a case of

"worst-case analysis run amok". In September 1986 Seitz published "Siberian fire as 'nuclear winter' guide" in the journal Nature

in which he investigated the 1915 Siberian fire which started in the

early summer months and was caused by the worst drought in the region's

recorded history. The fire ultimately devastated the region burning the

world's largest boreal forest,

the size of Germany. While approximately 8 ˚C of daytime summer cooling

occurred under the smoke clouds during the weeks of burning, no

increase in potentially devastating agricultural night frosts occurred.

Following his investigation into the Siberian fire of 1915, Seitz

criticized the "nuclear winter" model results for being based on

successive worst-case events: “The improbability of a string of 40 such

coin tosses coming up heads approaches that of a pat royal flush.

Yet it was represented as a "sophisticated one-dimensional model" – a

usage that is oxymoronic, unless applied to [the British model Lesley

Lawson] Twiggy.”

Seitz cited Carl Sagan, adding an emphasis: "In almost any realistic case

involving nuclear exchanges between the superpowers, global

environmental changes sufficient to cause an extinction event equal to

or more severe than that of the close of the Cretaceous when the dinosaurs and many other species died out are likely.” Seitz comments: “The ominous rhetoric

italicized in this passage puts even the 100 megaton [the original 100

city firestorm] scenario … on a par with the 100 million megaton blast

of an asteroid striking the Earth. This [is] astronomical mega-hype …” Seitz concludes:

As the science progressed and more authentic sophistication was achieved in newer and more elegant models, the postulated effects headed downhill. By 1986, these worst-case effects had melted down from a year of arctic darkness to warmer temperatures than the cool months in Palm Beach! A new paradigm of broken clouds and cool spots had emerged. The once global hard frost had retreated back to the northern tundra. Mr. Sagan's elaborate conjecture had fallen prey to Murphy's lesser-known Second Law: If everything MUST go wrong, don't bet on it.

Seitz's opposition caused the proponents of nuclear winter to issue

responses in the media. The proponents believed it was simply necessary

to show only the possibility of climatic catastrophe, often a worst-case

scenario, while opponents insisted that to be taken seriously, nuclear

winter should be shown as likely under "reasonable" scenarios.

One of these areas of contention, as elucidated by Lynn R. Anspaugh, is

upon the question of which season should be used as the backdrop for

the US-USSR war models, as most models choose the summer in the Northern

Hemisphere as the start point to produce the maximum soot lofting and

therefore eventual winter effect, whereas it has been pointed out that

if the firestorms occurred in the autumn or winter months, when there is

much less intense sunlight to loft soot into a stable region of the

stratosphere, the magnitude of the cooling effect from the same number

of firestorms as ignited in the summer models, would be negligible

according to a January model run by Covey et al. Schneider conceded the issue in 1990, saying "a war in late fall or winter would have no appreciable [cooling] effect".

Anspaugh also expressed frustration that although a managed

forest fire in Canada on 3 August 1985 is said to have been lit by

proponents of nuclear winter, with the fire potentially serving as an

opportunity to do some basic measurements of the optical properties of

the smoke and smoke-to-fuel ratio, which would have helped refine the

estimates of these critical model inputs, the proponents did not

indicate that any such measurements were made. Peter V. Hobbs,

who would later successfully attain funding to fly into and sample the

smoke clouds from the Kuwait oil fires in 1991, also expressed

frustration that he was denied funding to sample the Canadian, and other

forest fires in this way.

Turco wrote a 10-page memorandum with information derived from his

notes and some satellite images, claiming that the smoke plume reached

6 km in altitude.

In 1986, atmospheric scientist Joyce Penner from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory published an article in Nature

in which she focused on the specific variables of the smoke's optical

properties and the quantity of smoke remaining airborne after the city

fires and found that the published estimates of these variables varied

so widely that depending on which estimates were chosen the climate

effect could be negligible, minor or massive.

The assumed optical properties for black carbon in more recent nuclear

winter papers in 2006 are still "based on those assumed in earlier

nuclear winter simulations".

John Maddox, editor of the journal Nature, issued a series of skeptical comments about nuclear winter studies during his tenure.

Similarly S. Fred Singer was a long term vocal critic of the

hypothesis in the journal and in televised debates with Carl Sagan.

Critical response to the more modern papers

In a 2011 response to the more modern papers on the hypothesis, Russell Seitz published a comment in Nature challenging Alan Robock's claim that there has been no real scientific debate about the 'nuclear winter' concept. In 1986 Seitz also contends that many others are reluctant to speak out for fear of being stigmatized as "closet Dr. Strangeloves", physicist Freeman Dyson

of Princeton for example stated "It's an absolutely atrocious piece of

science, but I quite despair of setting the public record straight."

According to the Rocky Mountain News, Stephen Schneider had been called

a fascist by some disarmament supporters for having written his 1986

article "Nuclear Winter Reappraised." As MIT meteorologist Kerry Emanuel similarly wrote a review in Nature

that the winter concept is “notorious for its lack of scientific

integrity” due to the unrealistic estimates selected for the quantity of

fuel likely to burn, the imprecise global circulation models used, and

ends by stating that the evidence of other models, point to substantial

scavenging of the smoke by rain.

Emanuel also made an "interesting point" about questioning proponent's

objectivity when it came to strong emotional or political issues that

they hold.

William R. Cotton, Professor of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University, specialist in cloud physics modeling and co-creator of the highly influential, and previously mentioned RAMS atmosphere model, had in the 1980s worked on soot rain-out models and supported the predictions made by his own and other nuclear winter models,

but has since reversed this position according to a book co-authored by

him in 2007, stating that, amongst other systematically examined

assumptions, far more rain out/wet deposition of soot will occur than is

assumed in modern papers on the subject: "We must wait for a new

generation of GCMs

to be implemented to examine potential consequences quantitatively" and

revealing that in his experience, "nuclear winter was largely

politically motivated from the beginning".

Policy implications

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara called on the USSR to launch a nuclear first strike

against the US in the event of a US invasion of Cuba. In the 1980s

Castro was pressuring the Kremlin to adopt a harder line against the US

under President Ronald Reagan,

even arguing for the potential use of nuclear weapons. As a direct

result of this a Soviet official was dispatched to Cuba in 1985 with an

entourage of "experts", who detailed the ecological effect on Cuba in

the event of nuclear strikes on the United States. Soon after, the

Soviet official recounts, Castro lost his prior "nuclear fever".

In 2010 Alan Robock was summoned to Cuba to help Castro promote his new

view that nuclear war would bring about Armageddon. Robock's 90 minute

lecture was later aired on the nationwide state-controlled television

station in the country.

However, according to Robock, insofar as getting US government

attention and affecting nuclear policy, he has failed. In 2009, together

with Owen Toon, he gave a talk to the United States Congress but nothing transpired from it and the then presidential science adviser, John Holdren, did not respond to their requests in 2009 or at the time of writing in 2011.

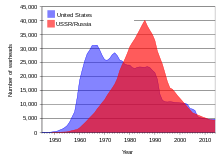

United

States and Soviet Union nuclear stockpiles. The effects of trying to

make others believe the results of the models on nuclear winter, does

not appear to have decreased either country's nuclear stockpiles in the

1980s, only the failing Soviet economy and the dissolution of the country between 1989–91 which marks the end of the Cold War and with it the relaxation of the "arms race", appears to have had an effect. The effects of the electricity generating Megatons to Megawatts

program can also be seen in the mid 1990s, continuing the trend in

Russian reductions. A similar chart focusing solely on quantity of

warheads in the multi-megaton range is also available. Moreover, total deployed US and Russian strategic weapons increased steadily from 1983 until the Cold War ended.

In a 2012 "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists" feature, Robock and

Toon, who had routinely mixed their disarmament advocacy into the

conclusions of their "nuclear winter" papers,

argue in the political realm that the hypothetical effects of nuclear

winter necessitates that the doctrine they assume is active in Russia

and US, "mutually assured destruction" (MAD) should instead be replaced with their own "self-assured destruction" (SAD) concept,

because, regardless of whose cities burned, the effects of the

resultant nuclear winter that they advocate, would be, in their view,

catastrophic. In a similar vein, in 1989 Carl Sagan and Richard Turco

wrote a policy implications paper that appeared in AMBIO that

suggested that as nuclear winter is a "well-established prospect", both

superpowers should jointly reduce their nuclear arsenals to "Canonical Deterrent Force"

levels of 100–300 individual warheads each, such that in "the event of

nuclear war [this] would minimize the likelihood of [extreme] nuclear

winter."

An originally classified 1984 US interagency intelligence assessment states that in both the preceding 1970s and 80s, the Soviet and US military were already following the "existing trends" in warhead miniaturization, of higher accuracy and lower yield nuclear warheads, this is seen when assessing the most numerous physics packages in the US arsenal, which in the 1960s were the B28 and W31, however both quickly became less prominent with the 1970s mass production runs of the 50 Kt W68, the 100 Kt W76 and in the 1980s, with the B61. This trend towards miniaturization, enabled by advances in inertial guidance and accurate GPS

navigation etc., was motivated by a multitude of factors, namely the

desire to leverage the physics of equivalent megatonnage that

miniaturization offered; of freeing up space to fit more MIRV warheads and decoys on each missile. Alongside the desire to still destroy hardened targets but while reducing the severity of fallout collateral damage

depositing on neighboring, and potentially friendly, countries. As it

relates to the likelihood of nuclear winter, the range of potential thermal radiation

ignited fires was already reduced with miniaturization. For example,

the most popular nuclear winter paper, the 1983 TTAPS paper, had

described a 3000 Mt counterforce attack on ICBM

sites with each individual warhead having approximately one Mt of

energy; however not long after publication, Michael Altfeld of Michigan State University and political scientist Stephen Cimbala of Pennsylvania State University argued that the then already developed and deployed smaller, more accurate warheads (e.g. W76), together with lower detonation heights, could produce the same counterforce strike with a total of only 3 Mt of energy being expended. They continue that, if

the nuclear winter models prove to be representative of reality, then

far less climatic-cooling would occur, even if firestorm prone areas

existed in the target list,

as lower fusing heights such as surface bursts, would also limit the

range of the burning thermal rays due to terrain masking and shadows

cast by buildings, while also temporarily lofting far more localized fallout when compared to airburst fuzing – the standard mode of employment against un-hardened targets.

The 1951 Shot Uncle of Operation Buster-Jangle, had a yield about a tenth of the 13 to 16 Kt Hiroshima bomb, 1.2 Kt, and was detonated 5.2 m (17 ft) beneath ground level. No thermal flash of heat energy was emitted to the surroundings in this shallow buried test. The explosion resulted in a cloud that rose to 3.5 km (11,500 ft). The resulting crater was 260 feet wide and 53 feet deep. The yield is similar to that of an Atomic Demolition Munition.

Altfeld and Cimbala argue that true belief in nuclear winter might lead

nations towards building greater arsenals of weapons of this type. However, despite being complicated due to the advent of Dial-a-yield

technology, data on these low yield nuclear weapons suggests that they,

as of 2012, make up about a tenth of the arsenal of the US and Russia,

and the fraction of the stockpile that they occupy has diminished since

the 1970-90s, not grown.

A factor in this is that very thin devices with yields approximately

around 1 kiloton of energy are nuclear weapons that make very

inefficient use of their nuclear materials, e.g. two-point implosion. Thus a more psychologically detering higher efficiency/higher yield device, can instead be constructed from the same mass of fissile material.

This logic is similarly reflected in the originally classified 1984 Interagency Intelligence assessment,

which suggests that targeting planners would simply have to consider

target combustibility along with yield, height of burst, timing and

other factors to reduce the amount of smoke to safeguard against the

potentiality of a nuclear winter.

Therefore, as a consequence of attempting to limit the target fire

hazard by reducing the range of thermal radiation with fuzing for

surface and sub-surface bursts, this will result in a scenario where the far more concentrated, and therefore deadlier, local fallout that is generated following a surface burst forms, as opposed to the comparatively dilute global fallout created when nuclear weapons are fuzed in air burst mode.

Altfeld and Cimbala also argued that belief in the possibility of

nuclear winter would actually make nuclear war more likely, contrary to

the views of Sagan and others, because it would serve yet further

motivation to follow the existing trends, towards the development of more accurate, and even lower explosive yield, nuclear weapons. As the winter hypothesis suggests that the replacement of the then Cold War viewed strategic nuclear weapons in the multi-megaton yield range, with weapons of explosive yields closer to tactical nuclear weapons, such as the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator

(RNEP), would safeguard against the nuclear winter potential. With the

latter capabilities of the then, largely still conceptual RNEP,

specifically cited by the influential nuclear warfare analyst Albert Wohlstetter. Tactical nuclear weapons, on the low end of the scale have yields that overlap with large conventional weapons,

and are therefore often viewed "as blurring the distinction between

conventional and nuclear weapons", making the prospect of using them

"easier" in a conflict.

Soviet exploitation

In an interview in 2000 with Mikhail Gorbachev