Robert Fludd's

1618 "water screw" perpetual motion machine from a 1660 wood engraving.

This device is widely credited as the first recorded attempt to

describe such a device in order to produce useful work, that of driving

millstones. Although the machine would not work, the idea was that water from the top tank turns a water wheel (bottom-left), which drives a complicated series of gears and shafts that ultimately rotate the Archimedes' screw

(bottom-center to top-right) to pump water to refill the tank. The

rotary motion of the water wheel also drives two grinding wheels

(bottom-right) and is shown as providing sufficient excess water to

lubricate them.

Perpetual motion is motion of bodies that continues indefinitely. A perpetual motion machine

is a hypothetical machine that can do work indefinitely without an

energy source. This kind of machine is impossible, as it would violate

the first or second law of thermodynamics.

These laws of thermodynamics

apply regardless of the size of the system. For example, the motions

and rotations of celestial bodies such as planets may appear perpetual,

but are actually subject to many processes that slowly dissipate their

kinetic energy, such as solar wind, interstellar medium resistance, gravitational radiation and thermal radiation, so they will not keep moving forever.

Thus, machines that extract energy from finite sources will not

operate indefinitely, because they are driven by the energy stored in

the source, which will eventually be exhausted. A common example is

devices powered by ocean currents, whose energy is ultimately derived

from the Sun, which itself will eventually burn out.

Machines powered by more obscure sources have been proposed, but are

subject to the same inescapable laws, and will eventually wind down.

In 2017, new states of matter, time crystals,

were discovered in which on a microscopic scale the component atoms are

in continual repetitive motion, thus satisfying the literal definition

of "perpetual motion".

However, these do not constitute perpetual motion machines in the

traditional sense or violate thermodynamic laws because they are in

their quantum ground state, so no energy can be extracted from them; they have "motion without energy".

History

The history of perpetual motion machines dates back to the Middle

Ages. For millennia, it was not clear whether perpetual motion devices

were possible or not, but the development of modern theories of

thermodynamics has shown that they are impossible. Despite this, many

attempts have been made to construct such machines, continuing into

modern times. Modern designers and proponents often use other terms,

such as "over unity", to describe their inventions.

Basic principles

Oh ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued? Go and take your place with the alchemists.

— Leonardo da Vinci, 1494

There is a scientific consensus that perpetual motion in an isolated system violates either the first law of thermodynamics, the second law of thermodynamics, or both. The first law of thermodynamics is a version of the law of conservation of energy. The second law can be phrased in several different ways, the most intuitive of which is that heat

flows spontaneously from hotter to colder places; relevant here is that

the law observes that in every macroscopic process, there is friction

or something close to it; another statement is that no heat engine (an engine which produces work while moving heat from a high temperature to a low temperature) can be more efficient than a Carnot heat engine.

In other words:

- In any isolated system, one cannot create new energy (law of conservation of energy). As a result, the thermal efficiency—the produced work power divided by the input heating power—cannot be greater than one.

- The output work power of heat engines is always smaller than the input heating power. The rest of the heat energy supplied is wasted as heat to the ambient surroundings. The thermal efficiency therefore has a maximum, given by the Carnot efficiency, which is always less than one.

- The efficiency of real heat engines is even lower than the Carnot efficiency due to irreversibility arising from the speed of processes, including friction.

Statements 2 and 3 apply to heat engines. Other types of engines

which convert e.g. mechanical into electromagnetic energy, cannot

operate with 100% efficiency, because it is impossible to design any

system that is free of energy dissipation.

Machines which comply with both laws of thermodynamics by

accessing energy from unconventional sources are sometimes referred to

as perpetual motion machines, although they do not meet the standard

criteria for the name. By way of example, clocks and other low-power

machines, such as Cox's timepiece,

have been designed to run on the differences in barometric pressure or

temperature between night and day. These machines have a source of

energy, albeit one which is not readily apparent so that they only seem

to violate the laws of thermodynamics.

Even machines which extract energy from long-lived sources - such

as ocean currents - will run down when their energy sources inevitably

do. They are not perpetual motion machines because they are consuming

energy from an external source and are not isolated systems.

Classification

One classification of perpetual motion machines refers to the particular law of thermodynamics the machines purport to violate:

- A perpetual motion machine of the first kind produces work without the input of energy. It thus violates the first law of thermodynamics: the law of conservation of energy.

- A perpetual motion machine of the second kind is a machine which spontaneously converts thermal energy into mechanical work. When the thermal energy is equivalent to the work done, this does not violate the law of conservation of energy. However, it does violate the more subtle second law of thermodynamics. The signature of a perpetual motion machine of the second kind is that there is only one heat reservoir involved, which is being spontaneously cooled without involving a transfer of heat to a cooler reservoir. This conversion of heat into useful work, without any side effect, is impossible, according to the second law of thermodynamics.

- A perpetual motion machine of the third kind is usually (but not always) defined as one that completely eliminates friction and other dissipative forces, to maintain motion forever (due to its mass inertia). (Third in this case refers solely to the position in the above classification scheme, not the third law of thermodynamics.) It is impossible to make such a machine, as dissipation can never be completely eliminated in a mechanical system, no matter how close a system gets to this ideal (see examples in the Low Friction section).

Impossibility

October 1920 issue of Popular Science

magazine, on perpetual motion. Although scientists have established

them to be impossible under the laws of physics, perpetual motion

continues to capture the imagination of inventors. The device shown is a

"mass leverage" device, where the spherical weights on the right have

more leverage than those on the left, supposedly creating a perpetual

rotation. However, there are a greater number of weights on the left,

balancing the device.

"Epistemic impossibility" describes things which absolutely cannot occur within our current

formulation of the physical laws. This interpretation of the word

"impossible" is what is intended in discussions of the impossibility of

perpetual motion in a closed system.

The conservation laws are particularly robust from a mathematical perspective. Noether's theorem, which was proven mathematically in 1915, states that any conservation law can be derived from a corresponding continuous symmetry of the action of a physical system.

For example, if the true laws of physics remain invariant over time

then the conservation of energy follows. On the other hand, if the

conservation laws are invalid, then the foundations of physics would

need to change.

Scientific investigations as to whether the laws of physics are

invariant over time use telescopes to examine the universe in the

distant past to discover, to the limits of our measurements, whether

ancient stars were identical to stars today. Combining different

measurements such as spectroscopy, direct measurement of the speed of light in the past

and similar measurements demonstrates that physics has remained

substantially the same, if not identical, for all of observable time

spanning billions of years.

The principles of thermodynamics are so well established, both

theoretically and experimentally, that proposals for perpetual motion

machines are universally met with disbelief on the part of physicists.

Any proposed perpetual motion design offers a potentially instructive

challenge to physicists: one is certain that it cannot work, so one must

explain how it fails to work. The difficulty (and the value) of

such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones

tend to arise from physicists' own thought experiments and often shed light upon certain aspects of physics. So, for example, the thought experiment of a Brownian ratchet as a perpetual motion machine was first discussed by Gabriel Lippmann in 1900 but it was not until 1912 that Marian Smoluchowski gave an adequate explanation for why it cannot work.

However, during that twelve-year period scientists did not believe

that the machine was possible. They were merely unaware of the exact

mechanism by which it would inevitably fail.

The law that entropy always increases, holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.

— Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

In the mid 19th-century Henry Dircks

investigated the history of perpetual motion experiments, writing a

vitriolic attack on those who continued to attempt what he believed to

be impossible:

There is something lamentable, degrading, and almost insane in pursuing the visionary schemes of past ages with dogged determination, in paths of learning which have been investigated by superior minds, and with which such adventurous persons are totally unacquainted. The history of Perpetual Motion is a history of the fool-hardiness of either half-learned, or totally ignorant persons.

— Henry Dircks, Perpetuum Mobile: Or, A History of the Search for Self-motive (1861)

Techniques

| “ | One day man will connect his apparatus to the very wheelwork of the universe [...] and the very forces that motivate the planets in their orbits and cause them to rotate will rotate his own machinery. | ” |

| — Nikola Tesla | ||

Some common ideas recur repeatedly in perpetual motion machine

designs. Many ideas that continue to appear today were stated as early

as 1670 by John Wilkins, Bishop of Chester and an official of the Royal Society. He outlined three potential sources of power for a perpetual motion machine, "Chymical [sic] Extractions", "Magnetical Virtues" and "the Natural Affection of Gravity".

The seemingly mysterious ability of magnets

to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source

has long appealed to inventors. One of the earliest examples of a

magnetic motor was proposed by Wilkins and has been widely copied since:

it consists of a ramp with a magnet at the top, which pulled a metal

ball up the ramp. Near the magnet was a small hole that was supposed to

allow the ball to drop under the ramp and return to the bottom, where a

flap allowed it to return to the top again. The device simply could not

work. Faced with this problem, more modern versions typically use a

series of ramps and magnets, positioned so the ball is to be handed off

from one magnet to another as it moves. The problem remains the same.

Perpetuum Mobile of Villard de Honnecourt (about 1230).

The "Overbalanced Wheel".

Gravity

also acts at a distance, without an apparent energy source, but to get

energy out of a gravitational field (for instance, by dropping a heavy

object, producing kinetic energy as it falls) one has to put energy in

(for instance, by lifting the object up), and some energy is always

dissipated in the process. A typical application of gravity in a

perpetual motion machine is Bhaskara's

wheel in the 12th century, whose key idea is itself a recurring theme,

often called the overbalanced wheel: moving weights are attached to a

wheel in such a way that they fall to a position further from the

wheel's center for one half of the wheel's rotation, and closer to the

center for the other half. Since weights further from the center apply a

greater torque,

it was thought that the wheel would rotate for ever. However, since the

side with weights further from the center has fewer weights than the

other side, at that moment, the torque is balanced and perpetual

movement is not achieved. The moving weights may be hammers on pivoted arms, or rolling balls, or mercury in tubes; the principle is the same.

Perpetual motion wheels from a drawing of Leonardo da Vinci.

Another theoretical machine involves a frictionless environment for motion. This involves the use of diamagnetic or electromagnetic levitation to float an object. This is done in a vacuum

to eliminate air friction and friction from an axle. The levitated

object is then free to rotate around its center of gravity without

interference. However, this machine has no practical purpose because the

rotated object cannot do any work as work requires the levitated object

to cause motion in other objects, bringing friction into the problem.

Furthermore, a perfect vacuum is an unattainable goal since both the container and the object itself would slowly vaporize, thereby degrading the vacuum.

To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion

machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at

least to Maxwell's demon) is unidirectionality. Only molecules moving fast enough and in the right direction are allowed through the demon's trap door. In a Brownian ratchet,

forces tending to turn the ratchet one way are able to do so while

forces in the other direction are not. A diode in a heat bath allows

through currents in one direction and not the other. These schemes

typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality

costs energy (requiring Maxwell's demon to perform more thermodynamic

work to gauge the speed of the molecules than the amount of energy

gained by the difference of temperature caused) or the unidirectionality

is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent

small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal

Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way).

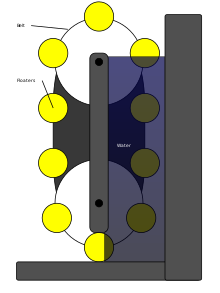

The

"Float Belt". The yellow blocks indicate floaters. It was thought that

the floaters would rise through the liquid and turn the belt. However,

pushing the floaters into the water at the bottom takes as much energy

as the floating generates, and some energy is dissipated.

Buoyancy

is another frequently misunderstood phenomenon. Some proposed

perpetual-motion machines miss the fact that to push a volume of air

down in a fluid takes the same work as to raise a corresponding volume

of fluid up against gravity. These types of machines may involve two

chambers with pistons, and a mechanism to squeeze the air out of the top

chamber into the bottom one, which then becomes buoyant and floats to

the top. The squeezing mechanism in these designs would not be able to

do enough work to move the air down, or would leave no excess work

available to be extracted.

Patents

Proposals for such inoperable machines have become so common that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has made an official policy of refusing to grant patents for perpetual motion machines without a working model. The USPTO Manual of Patent Examining Practice states:

With the exception of cases involving perpetual motion, a model is not ordinarily required by the Office to demonstrate the operability of a device. If operability of a device is questioned, the applicant must establish it to the satisfaction of the examiner, but he or she may choose his or her own way of so doing.

And, further, that:

A rejection [of a patent application] on the ground of lack of utility includes the more specific grounds of inoperativeness, involving perpetual motion. A rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 for lack of utility should not be based on grounds that the invention is frivolous, fraudulent or against public policy.

The filing of a patent application is a clerical task, and the USPTO

will not refuse filings for perpetual motion machines; the application

will be filed and then most probably rejected by the patent examiner,

after he has done a formal examination.

Even if a patent is granted, it does not mean that the invention

actually works, it just means that the examiner believes that it works,

or was unable to figure out why it would not work.

The USPTO maintains a collection of Perpetual Motion Gimmicks.

The United Kingdom Patent Office has a specific practice on perpetual motion; Section 4.05 of the UKPO Manual of Patent Practice states:

Processes or articles alleged to operate in a manner which is clearly contrary to well-established physical laws, such as perpetual motion machines, are regarded as not having industrial application.

Examples of decisions by the UK Patent Office to refuse patent applications for perpetual motion machines include:

- Decision BL O/044/06, John Frederick Willmott's application no. 0502841

- Decision BL O/150/06, Ezra Shimshi's application no. 0417271

The European Patent Classification

(ECLA) has classes including patent applications on perpetual motion

systems: ECLA classes "F03B17/04: Alleged perpetua mobilia ..." and

"F03B17/00B: [... machines or engines] (with closed loop circulation or

similar : ... Installations wherein the liquid circulates in a closed

loop; Alleged perpetua mobilia of this or similar kind ...".

Apparent perpetual motion machines

As

"perpetual motion" can exist only in isolated systems, and true

isolated systems do not exist, there are not any real "perpetual motion"

devices. However, there are concepts and technical drafts that propose

"perpetual motion", but on closer analysis it is revealed that they

actually "consume" some sort of natural resource or latent energy, such

as the phase changes of water

or other fluids or small natural temperature gradients, or simply

cannot sustain indefinite operation. In general, extracting work from

these devices is impossible.

Resource consuming

The "Capillary Bowl"

Some examples of such devices include:

- The drinking bird toy functions using small ambient temperature gradients and evaporation. It runs until all water is evaporated.

- A capillary action-based water pump functions using small ambient temperature gradients and vapour pressure differences. With the "Capillary Bowl", it was thought that the capillary action would keep the water flowing in the tube, but since the cohesion force that draws the liquid up the tube in the first place holds the droplet from releasing into the bowl, the flow is not perpetual.

- A Crookes radiometer consists of a partial vacuum glass container with a lightweight propeller moved by (light-induced) temperature gradients.

- Any device picking up minimal amounts of energy from the natural electromagnetic radiation around it, such as a solar powered motor.

- Any device powered by changes in air pressure, such as some clocks (Cox's timepiece, Beverly Clock). The motion leeches energy from moving air which in turn gained its energy from being acted on.

- The Atmos clock uses changes in the vapor pressure of ethyl chloride with temperature to wind the clock spring.

- A device powered by radioactive decay from an isotope with a relatively long half-life; such a device could plausibly operate for hundreds or thousands of years.

- The Oxford Electric Bell and Karpen Pile driven by dry pile batteries.

Low friction

- In flywheel energy storage, "modern flywheels can have a zero-load rundown time measurable in years".

- Once spun up, objects in the vacuum of space—stars, black holes, planets, moons, spin-stabilized satellites, etc.—dissipate energy very slowly, allowing them to spin for long periods. Tides on Earth are dissipating the gravitational energy of the Moon/Earth system at an average rate of about 3.75 terawatts.

- In certain quantum-mechanical systems (such as superfluidity and superconductivity), very low friction movement is possible. However, the motion stops when the system reaches an equilibrium state (e.g. all the liquid helium arrives at the same level.) Similarly, seemingly entropy-reversing effects like superfluids climbing the walls of containers operate by ordinary capillary action.

Thought experiments

In some cases a thought (or gedanken)

experiment appears to suggest that perpetual motion may be possible

through accepted and understood physical processes. However, in all

cases, a flaw has been found when all of the relevant physics is

considered. Examples include:

- Maxwell's demon: This was originally proposed to show that the Second Law of Thermodynamics applied in the statistical sense only, by postulating a "demon" that could select energetic molecules and extract their energy. Subsequent analysis (and experiment) have shown there is no way to physically implement such a system that does not result in an overall increase in entropy.

- Brownian ratchet: In this thought experiment, one imagines a paddle wheel connected to a ratchet. Brownian motion would cause surrounding gas molecules to strike the paddles, but the ratchet would only allow it to turn in one direction. A more thorough analysis showed that when a physical ratchet was considered at this molecular scale, Brownian motion would also affect the ratchet and cause it to randomly fail resulting in no net gain. Thus, the device would not violate the Laws of thermodynamics.

- Vacuum energy and zero-point energy: In order to explain effects such as virtual particles and the Casimir effect, many formulations of quantum physics include a background energy which pervades empty space, known as vacuum or zero-point energy. The ability to harness zero-point energy for useful work is considered pseudoscience by the scientific community at large. Inventors have proposed various methods for extracting useful work from zero-point energy, but none have been found to be viable, no claims for extraction of zero-point energy have ever been validated by the scientific community, and there is no evidence that zero-point energy can be used in violation of conservation of energy.