The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that it looks at the economic distribution of ownership of the assets in a society, rather than the current income of members of that society. According to the International Association for Research in Income and Wealth, "the world distribution of wealth is much more unequal than that of income."

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that it looks at the economic distribution of ownership of the assets in a society, rather than the current income of members of that society. According to the International Association for Research in Income and Wealth, "the world distribution of wealth is much more unequal than that of income."

Definition of wealth

A broader definition of wealth, which is rarely used in the measurement of wealth inequality, also includes human capital. For example, the United Nations definition of inclusive wealth is a monetary measure which includes the sum of natural, human and physical assets.

The relation between wealth, income, and expenses is: :change of

wealth = saving = income − consumption(expenses). If an individual has a

large income but also large expenses, the net effect of that income on

her or his wealth could be small or even negative.

The term wealth should not be confused with rich.

These two terms describe different but related things. Wealth consists

of those items of economic value that an individual owns, while rich is

an inflow of items of economic value.

Wealth concentration

Wealth concentration is a process by which created wealth, under some conditions, can become concentrated by individuals or entities. Those who hold wealth have the means to invest

in newly created sources and structures of wealth, or to otherwise

leverage the accumulation of wealth, and are thus the beneficiaries of

even greater wealth.

Conceptual framework

There

are many ways in which the distribution of wealth can be analyzed. One

common-used example is to compare the amount of the wealth of individual

at say 99 percentile relative to the wealth of the median (or 50th)

percentile. This is P99/P50, which is one of the potential Kuznets ratios.

Another common measure is the ratio of total amount of wealth in the

hand of top say 1% of the wealth distribution over the total wealth in

the economy. In many societies, the richest ten percent control more

than half of the total wealth.

Pareto Distribution

has often been used to mathematically quantify the distribution of

wealth at the right tail (the wealth of very rich). In fact, the tail of

wealth distribution, similar to the one of income distribution, behave

like Pareto distribution but with ticker tail.

Wealth over people (WOP) curves are a visually compelling

way to show the distribution of wealth in a nation. WOP curves are

modified distribution of wealth curves. The vertical and horizontal

scales each show percentages from zero to one hundred. We imagine all

the households in a nation being sorted from richest to poorest. They

are then shrunk down and lined up (richest at the left) along the

horizontal scale. For any particular household, its point on the curve

represents how their wealth compares (as a proportion) to the average

wealth of the richest percentile. For any nation, the average wealth of

the richest 1/100 of households is the topmost point on the curve

(people, 1%; wealth, 100%) or (p=1, w=100) or (1, 100). In the real

world two points on the WOP curve are always known before any statistics

are gathered. These are the topmost point (1, 100) by definition, and

the rightmost point (poorest people, lowest wealth) or (p=100, w=0) or

(100, 0). This unfortunate rightmost point is given because there are

always at least one percent of households (incarcerated, long term

illness, etc.) with no wealth at all. Given that the topmost and

rightmost points are fixed ... our interest lies in the form of the WOP

curve between them. There are two extreme possible forms of the curve.

The first is the "perfect communist" WOP. It is a straight line from the

leftmost (maximum wealth) point horizontally across the people scale to

p=99. Then it drops vertically to wealth = 0 at (p=100, w=0).

The other extreme is the "perfect tyranny" form. It starts on the

left at the Tyrant's maximum wealth of 100%. It then immediately drops

to zero at p=2, and continues at zero horizontally across the rest of

the people. That is, the tyrant and his friends (the top percentile) own

all the nation's wealth. All other citizens are serfs or slaves. An

obvious intermediate form is a straight line connecting the left/top

point to the right/bottom point. In such a "Diagonal" society a

household in the richest percentile would have just twice the wealth of a

family in the median (50th) percentile. Such a society is compelling to

many (especially the poor). In fact it is a comparison to a diagonal

society that is the basis for the Gini values

used as a measure of the disequity in a particular economy. These Gini

values (40.8 in 2007) show the United States to be the third most

dis-equitable economy of all the developed nations (behind Denmark and

Switzerland).

Available Data

Wealth surveys

Many countries have national wealth surveys, for example:

- The British Wealth and Assets Survey

- The Italian Survey on Household Income and Wealth

- The euro area Household Finance and Consumption Survey

- The US Survey of Consumer Finances

- The Canadian Survey of Financial Security

- The German Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht der Bundesregierung

Inequality

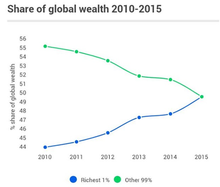

The gap between the rich and poor can be illustrated by the fact that

the three wealthiest individuals in the world have assets that exceed

those of the poorest 10 percent of the world's population. The net worth of the world's billionaires increased from less than $1 trillion in 2000 to over $7 trillion in 2015 so the gap is increasing dramatically.

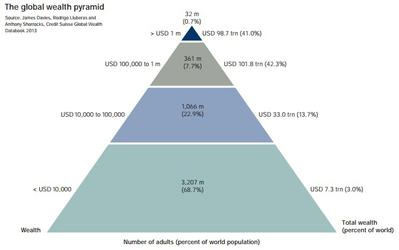

Wealth distribution pyramid

Personal

wealth varies across adults for many reasons. Some individuals with

little wealth may be at early stages in their careers, with little

chance or motivation to accumulate assets. Others may have suffered

business setbacks or personal misfortunes, or live in parts of the world

where opportunities for wealth creation are severely limited. At the

other end of the spectrum, there are individuals who have acquired a

large wealth through different ways. In Western countries, the most typical way of becoming wealthy is entrepreneurship

(estimated three quarters of new millionaires). Other typical way

(covering most of the remaining quarter) is pursuing a career with the

end goal of becoming a C-level executive,

a leading professional in a specific field (such as a doctor, lawyer,

engineer) or a top corporate sales person. Only around 1% of new

millionaires acquire their wealth via other means such as professional

sports, show business, art, inventions, investing, inheritance or

lottery.

The wealth pyramid below was prepared by Credit Suisse in 2013. Personal assets were calculated in net worth, meaning wealth would be negated by having any mortgages.

It has a large base of low wealth holders, alongside upper tiers

occupied by progressively fewer people. In 2013 Credit-suisse estimate

that 3.2 billion individuals – more than two thirds of adults in the

world – have wealth below US$10,000. A further one billion(adult

population) fall within the 10,000 – US$100,000 range. While the average

wealth holding is modest in the base and middle segments of the

pyramid, their total wealth amounts to US$40 trillion, underlining the

potential for novel consumer products and innovative financial services

targeted

at this often neglected segment.

The pyramid shows that:

- half of the world's net wealth belongs to the top 1%,

- top 10% of adults hold 85%, while the bottom 90% hold the remaining 15% of the world's total wealth,

- top 30% of adults hold 97% of the total wealth.

Wealth distribution in 2012

According

to the OECD in 2012 the top 0.6% of world population (consisting of

adults with more than US$1 million in assets) or the 42 million richest

people in the world held 39.3% of world wealth. The next 4.4% (311

million people) held 32.3% of world wealth. The bottom 95% held 28.4% of

world wealth. The large gaps of the report get by the Gini index to

0.893, and are larger than gaps in global income inequality, measured in

2009 at 0.38.

For example, in 2012 the bottom 60% of the world population held same

wealth in 2012 as the people on Forbes' Richest list consisting of 1,226

richest billionaires of the world.

21st century

At the end of the 20th century, wealth was concentrated among the G8 and Western industrialized nations, along with several Asian and OPEC nations.

Wealth inequality

A study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research

at United Nations University reports that the richest 1% of adults

alone owned 40% of global assets in the year 2000, and that the richest

10% of adults accounted for 85% of the world total. The bottom half of

the world adult population owned 1% of global wealth. Moreover, another study found that the richest 2% own more than half of global household assets.

Real estate

While

sizeable numbers of households own no land, few have no income. For

example, the top 10% of land owners (all corporations) in Baltimore, Maryland own 58% of the taxable land value. The bottom 10% of those who own any land own less than 1% of the total land value. This form of analysis as well as Gini coefficient analysis has been used to support land value taxation.

Wealth concentration

Wealth concentration is a process by which created wealth, under some conditions, can become concentrated by individuals or entities. Those who hold wealth have the means to invest

in newly created sources and structures of wealth, or to otherwise

leverage the accumulation of wealth, and are thus the beneficiaries of

even greater wealth.

Economic conditions

The

first necessary condition for the phenomenon of wealth concentration to

occur is an unequal initial distribution of wealth. The distribution of

wealth throughout the population is often closely approximated by a Pareto distribution, with tails which decay as a power-law in wealth. According to PolitiFact and others, the 400 wealthiest Americans had "more wealth than half of all Americans combined." Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a "substantial head start". In September 2012, according to the Institute for Policy Studies, "over 60 percent" of the Forbes richest 400 Americans "grew up in substantial privilege".

The second condition is that a small initial inequality must, over time, widen into a larger inequality. This is an example of positive feedback in an economic system. A team from Jagiellonian University

produced statistical model economies showing that wealth condensation

can occur whether or not total wealth is growing (if it is not, this

implies that the poor could become poorer).

Joseph E. Fargione, Clarence Lehman and Stephen Polasky

demonstrated in 2011 that chance alone, combined with the deterministic

effects of compounding returns, can lead to unlimited concentration of

wealth, such that the percentage of all wealth owned by a few

entrepreneurs eventually approaches 100%.

Correlation between being rich and earning more

Given an initial condition in which wealth is unevenly distributed (i.e., a "wealth gap"), several non-exclusive economic mechanisms for wealth condensation have been proposed:

- A correlation between being rich and being given high paid employment (oligarchy).

- A marginal propensity to consume low enough that high incomes are correlated with people who have already made themselves rich (meritocracy).

- The ability of the rich to influence government disproportionately to their favor thereby increasing their wealth (plutocracy).

In the first case, being wealthy gives one the opportunity to earn

more through high paid employment (e.g., by going to elite schools). In

the second case, having high paid employment gives one the opportunity

to become rich (by saving your money). In the case of plutocracy, the

wealthy exert power over the legislative process, which enables them to

increase the wealth disparity. An example of this is the high cost of political campaigning in some countries, in particular in the US.

Because these mechanisms are non-exclusive, it is possible for

all three explanations to work together for a compounding effect,

increasing wealth concentration even further. Obstacles to restoring

wage growth might have more to do with the broader dysfunction of a

dollar dominated system particular to the US than with the role of the

extremely wealthy.

Counterbalances to wealth concentration include certain forms of taxation, in particular wealth tax, inheritance tax and progressive taxation of income. However, concentrated wealth does not necessarily inhibit wage growth for ordinary workers.

Markets with social influence

Product

recommendations and information about past purchases have been shown to

influence consumers choices significantly whether it is for music,

movie, book, technological, and other type of products. Social influence

often induces a rich-get-richer phenomenon (Matthew effect) where popular products tend to become even more popular.

Redistribution of wealth and public policy

In many societies, attempts have been made, through property redistribution, taxation, or regulation, to redistribute wealth, sometimes in support of the upper class, and sometimes to diminish economic inequality.

Examples of this practice go back at least to the Roman republic in the third century B.C.,

when laws were passed limiting the amount of wealth or land that could

be owned by any one family. Motivations for such limitations on wealth

include the desire for equality of opportunity, a fear that great wealth

leads to political corruption, to the belief that limiting wealth will

gain the political favor of a voting bloc, or fear that extreme concentration of wealth results in rebellion. Various forms of socialism

attempt to diminish the unequal distribution of wealth and thus the

conflicts and social problems (see image below) arising from it.

During the Age of Reason, Francis Bacon

wrote "Above all things good policy is to be used so that the treasures

and monies in a state be not gathered into a few hands… Money is like

fertilizer, not good except it be spread."

Communism arose as a reaction to a distribution of wealth in which a few lived in luxury while the masses lived in extreme poverty. In the Critique of the Gotha Program, Marx and Engels wrote "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need."

While the ideas of Marx have nominally been embraced by various states

(Russia, Cuba, Vietnam and China in the 20th century), Marxist utopia

remains elusive.

On the other hand, the combination of labor movements, technology, and social liberalism has diminished extreme poverty in the developed world today, though extremes of wealth and poverty continue in the Third World.

In the Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014 from the World Economic Forum the widening income disparities come second as a worldwide risk.