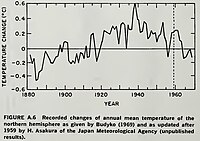

Mean

temperature anomalies during the period 1965 to 1975 with respect to

the average temperatures from 1937 to 1946. This dataset was not

available at the time.

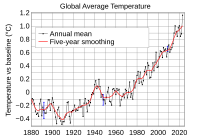

Global cooling was a conjecture during the 1970s of imminent cooling of the Earth's surface and atmosphere culminating in a period of extensive glaciation.

Press reports at the time did not accurately reflect the full scope of the debate in the scientific literature. The current scientific opinion on climate change is that the Earth underwent global warming throughout the 20th century and continues to warm.

Introduction: general awareness and concern

By

the 1970s, scientists were becoming increasingly aware that estimates

of global temperatures showed cooling since 1945, as well as the

possibility of large scale warming due to emissions of greenhouse gases.

In the scientific papers which considered climate trends of the 21st

century, less than 10% inclined towards future cooling, while most

papers predicted future warming. The general public had little awareness of carbon dioxide's effects on climate, but Science News

in May 1959 forecast a 25% increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide in

the 150 years from 1850 to 2000, with a consequent warming trend. The actual increase in this period was 29%. Paul R. Ehrlich mentioned climate change from greenhouse gases in 1968.

By the time the idea of global cooling reached the public press in the

mid-1970s temperatures had stopped falling, and there was concern in the

climatological community about carbon dioxide's warming effects. In response to such reports, the World Meteorological Organization issued a warning in June 1976 that "a very significant warming of global climate" was probable.

Currently, there are some concerns about the possible regional cooling effects of a slowdown or shutdown of thermohaline circulation, which might be provoked by an increase of fresh water mixing into the North Atlantic due to glacial melting. The probability of this occurring is generally considered to be very low, and the IPCC notes, "even in models where the THC weakens, there is still a warming over Europe. For example, in all AOGCM integrations where the radiative forcing is increasing, the sign of the temperature change over north-west Europe is positive."

Physical mechanisms

The cooling period is reproduced by current (1999 on) global climate models (GCMs) that include the physical effects of sulfate aerosols, and there is now general agreement that aerosol

effects were the dominant cause of the mid-20th century cooling. At the

time there were two physical mechanisms that were most frequently

advanced to cause cooling: aerosols and orbital forcing.

Aerosols

Human activity — mostly as a by-product of fossil fuel combustion, partly by land use changes — increases the number of tiny particles (aerosols) in the atmosphere. These have a direct effect: they effectively increase the planetary albedo, thus cooling the planet by reducing the solar radiation reaching the surface; and an indirect effect: they affect the properties of clouds by acting as cloud condensation nuclei. In the early 1970s some speculated that this cooling effect might dominate over the warming effect of the CO2

release: see discussion of Rasool and Schneider (1971), below. As a

result of observations and a switch to cleaner fuel burning, this no

longer seems likely; current scientific work indicates that global warming

is far more likely. Although the temperature drops foreseen by this

mechanism have now been discarded in light of better theory and the

observed warming, aerosols are thought to have contributed a cooling

tendency (outweighed by increases in greenhouse gases) and also have

contributed to "Global Dimming."

Orbital forcing

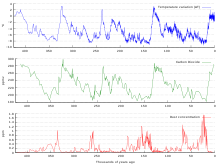

CO2, temperature, and dust concentration measured by Petit et al. from Vostok ice core at Antarctica.

Orbital forcing refers to the slow, cyclical changes in the tilt of Earth's axis and shape of its orbit.

These cycles alter the total amount of sunlight reaching the Earth by a

small amount and affect the timing and intensity of the seasons. This mechanism is thought to be responsible for the timing of the ice age cycles, and understanding of the mechanism was increasing rapidly in the mid-1970s.

The paper of Hays, Imbrie and Shackleton "Variations in the

Earth's Orbit: Pacemaker of the Ice Ages" qualified its predictions with

the remark that "forecasts must be qualified in two ways. First, they

apply only to the natural component of future climatic trends - and not

to anthropogenic effects such as those due to the burning of fossil

fuels. Second, they describe only the long-term trends, because they are

linked to orbital variations with periods of 20,000 years and longer. Climatic oscillations

at higher frequencies are not predicted... the results indicate that

the long-term trend over the next 20,000 years is towards extensive

Northern Hemisphere glaciation and cooler climate".

The idea that ice ages cycles were predictable appears to have

become conflated with the idea that another one was due "soon" - perhaps

because much of this study was done by geologists, who are accustomed

to dealing with very long time scales and use "soon" to refer to periods

of thousands of years. A strict application of the Milankovitch

theory does not allow the prediction of a "rapid" ice age onset (i.e.,

less than a century or two) since the fastest orbital period is about

20,000 years. Some creative ways around this were found, notably one

championed by Nigel Calder under the name of "snowblitz", but these ideas did not gain wide acceptance.

It is common to see it asserted that the length of the current interglacial

temperature peak is similar to the length of the preceding interglacial

peak (Sangamon/Eem), and from this conclude that we might be nearing

the end of this warm period. This conclusion is mistaken. Firstly,

because the lengths of previous interglacials were not particularly

regular. Petit et al. note that "interglacials 5.5 and 9.3 are different from the Holocene,

but similar to each other in duration, shape and amplitude. During each

of these two events, there is a warm period of 4 kyr followed by a

relatively rapid cooling". Secondly, future orbital variations will not

closely resemble those of the past.

Concern in the 1920s and 1930s

In 1923, there was concern about a new ice age and Captain Donald Baxter MacMillan sailed toward the Arctic sponsored by the National Geographical Society to look for evidence of advancing glaciers.

In 1926, a Berlin astronomer was predicting global cooling but that it was "ages away".

Concern in the 1940s and 1950s

Concerns that a new ice age was approaching was revived in the 1950s. During the Cold War, there were concerns by Harry Wexler that setting off atom bombs could be hastening a new ice age from a nuclear winter scenario.

Concern in the 1960s and 1970s

Pre-1970s

J. Murray Mitchell showed as early as 1963 a multidecadal cooling since about 1940. At a conference on climate change held in Boulder, Colorado in 1965, evidence supporting Milankovitch cycles triggered speculation on how the calculated small changes in sunlight might somehow trigger ice ages. In 1966, Cesare Emiliani predicted that "a new glaciation will begin within a few thousand years." In his 1968 book The Population Bomb, Paul R. Ehrlich wrote "The greenhouse effect is being enhanced now by the greatly increased level of carbon dioxide...

[this] is being countered by low-level clouds generated by contrails,

dust, and other contaminants... At the moment we cannot predict what the

overall climatic results will be of our using the atmosphere as a garbage dump."

1970s awareness

Concern peaked in the early 1970s, though "the possibility of anthropogenic warming dominated

the peer-reviewed literature even then" (a cooling period began in 1945, and two decades of a cooling trend

suggested a trough had been reached after several decades of warming).

This peaking concern is partially attributable to the fact much less was

then known about world climate and causes of ice ages.

Climate scientists were aware that predictions based on this trend were

not possible - because the trend was poorly studied and not understood

(for example see reference).

Despite that, in the popular press the possibility of cooling was

reported generally without the caveats present in the scientific

reports, and "unusually severe winters in Asia and parts of North

America in 1972 and 1973...pushed the issue into the public

consciousness".

In the 1970s, the compilation of records to produce hemispheric, or global, temperature records had just begun.

Spencer R. Weart's history of The Discovery of Global Warming states that: While

neither scientists nor the public could be sure in the 1970s whether

the world was warming or cooling, people were increasingly inclined to

believe that global climate was on the move, and in no small way.

On January 11, 1970, the Washington Post reported that "Colder Winters Held Dawn of New Ice Age".

In 1972, Emiliani warned "Man's activity may either precipitate

this new ice age or lead to substantial or even total melting of the ice

caps...". By 1972 a group of glacial-epoch experts at a conference agreed that "the natural end of our warm epoch is undoubtedly near";

but the volume of Quaternary Research reporting on the meeting said

that "the basic conclusion to be drawn from the discussions in this

section is that the knowledge necessary for understanding the mechanism

of climate change is still lamentably inadequate". Unless there were

impacts from future human activity, they thought that serious cooling

"must be expected within the next few millennia or even centuries"; but

many other scientists doubted these conclusions.

In 1972, George Kukla and Robert Matthews, in a Science

write-up of a conference, asked when and how the current interglacial

would end; concluding that "Global cooling and related rapid changes of

environment, substantially exceeding the fluctuations experienced by man

in historical times, must be expected within the next few millennia or

even centuries."

1970 SCEP report

The 1970 Study of Critical Environmental Problems reported the possibility of warming from increased carbon dioxide, but

no concerns about cooling, setting a lower bound on the beginning of

interest in "global cooling".

1971 to 1975: papers on warming and cooling factors

By 1971, studies indicated that human caused air pollution

was spreading, but there was uncertainty as to whether aerosols would

cause warming or cooling, and whether or not they were more significant

than rising CO2 levels. J. Murray Mitchell

still viewed humans as "innocent bystanders" in the cooling from the

1940s to 1970, but in 1971 his calculations suggested that rising

emissions could cause significant cooling after 2000, though he also

argued that emissions could cause warming depending on circumstances.

Calculations were too basic at this time to be trusted to give reliable

results.

An early numerical computation of climate effects was published in the journal Science in July 1971 as a paper by S. Ichtiaque Rasool and Stephen H. Schneider, titled "Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide and Aerosols: Effects of Large Increases on Global Climate".

The paper used rudimentary data and equations to compute the possible

future effects of large increases in the densities in the atmosphere of

two types of human environmental emissions:

- greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide;

- particulate pollution such as smog, some of which remains suspended in the atmosphere in aerosol form for years.

The paper suggested that the global warming due to greenhouse gases

would tend to have less effect with greater densities, and while aerosol

pollution could cause warming, it was likely that it would tend to have

a cooling effect which increased with density. They concluded that "An

increase by only a factor of 4 in global aerosol background

concentration may be sufficient to reduce the surface temperature by as

much as 3.5 ° K. If sustained over a period of several years, such a

temperature decrease over the whole globe is believed to be sufficient

to trigger an ice age."

Both their equations and their data were badly flawed, as was

soon pointed out by other scientists and confirmed by Schneider himself. In January 1972, Robert Jay Charlson et al. pointed out that with other reasonable assumptions, the model produced the opposite conclusion. The model made no allowance for changes in clouds or convection, and erroneously indicated that 8 times as much CO2 would only cause 2 °C of warming.

In a paper published in 1975, Schneider corrected the overestimate of

aerosol cooling by checking data on the effects of dust produced by

volcanoes. When the model included estimated changes in solar intensity,

it gave a reasonable match to temperatures over the previous thousand

years and its prediction was that "CO2 warming dominates the surface temperature patterns soon after 1980."

1972 and 1974 National Science Board

The National Science Board's Patterns and Perspectives in Environmental Science

report of 1972 discussed the cyclical behavior of climate, and the

understanding at the time that the planet was entering a phase of

cooling after a warm period. "Judging from the record of the past

interglacial ages, the present time of high temperatures should be

drawing to an end, to be followed by a long period of considerably

colder temperatures leading into the next glacial age some 20,000 years

from now."

But it also continued; "However, it is possible, or even likely, that

human interference has already altered the environment so much that the

climatic pattern of the near future will follow a different path."

The Board's report of 1974, Science And The Challenges Ahead,

continued on this theme. "During the last 20-30 years, world

temperature has fallen, irregularly at first but more sharply over the

last decade." Discussion of cyclic glacial periods

does not feature in this report. Instead it is the role of humans that

is central to the report's analysis.

"The cause of the cooling trend is not known with certainty. But there

is increasing concern that man himself may be implicated, not only in

the recent cooling trend but also in the warming temperatures over the

last century".

The report did not conclude whether carbon dioxide in warming, or

agricultural and industrial pollution in cooling, are factors in the

recent climatic changes, noting;

"Before such questions as these can be resolved, major advances must be

made in understanding the chemistry and physics of the atmosphere and oceans, and in measuring and tracing particulates through the system."

1975 National Academy of Sciences report

There also was a Report by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) entitled, "Understanding Climate Change: A Program for Action".

The report stated (p. 36) that, "The average surface air

temperature in the northern hemisphere increased from the 1880's until

about 1940 and has been decreasing thereafter."

It also stated (p. 44) that, "If both the CO

2 and particulate inputs to the atmosphere grow at equal rates in the future, the widely differing atmospheric residence times of the two pollutants means that the particulate effect will grow in importance relative to that of CO

2."

2 and particulate inputs to the atmosphere grow at equal rates in the future, the widely differing atmospheric residence times of the two pollutants means that the particulate effect will grow in importance relative to that of CO

2."

The report did not predict whether the 25-year cooling trend

would continue. It stated (Forward, p. v) that, "we do not have a good

quantitative understanding of our climate machine and what determines

its course [so] it does not seem possible to predict climate," and

(p. 2) "The climates of the earth have always been changing, and they

will doubtless continue to do so in the future. How large these future

changes will be, and where and how rapidly they will occur, we do not

know."

The Report's "program for action" was a call for creation of a

new "National Climatic Research Program." It stated (p. 62), "If we are

to react rationally to the inevitable climatic changes of the future,

and if we are ever to predict their future course, whether they are

natural or man-induced, a far greater understanding of these changes is

required than we now possess. It is, moreover, important that this

knowledge be acquired as soon as possible." For that reason, it stated,

"the time has now come to initiate a broad and coordinated attack on the

problem of climate and climatic change."

1974 Time magazine article

While

these discussions were ongoing in scientific circles, other accounts

appeared in the popular media. In their June 24, 1974 issue, Time

presented an article titled "Another Ice Age?" that noted "the

atmosphere has been growing gradually cooler for the past three decades"

but noted that "Some scientists... think that the cooling trend may be

only temporary."

1975 Newsweek article

An April 28, 1975 article in Newsweek magazine was titled "The Cooling World",

it pointed to "ominous signs that the Earth's weather patterns have

begun to change" and pointed to "a drop of half a degree [Fahrenheit] in

average ground temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere between 1945 and

1968." The article stated "The evidence in support of these predictions

[of global cooling] has now begun to accumulate so massively that

meteorologists are hard-pressed to keep up with it." The Newsweek

article did not state the cause of cooling; it stated that "what causes

the onset of major and minor ice ages remains a mystery" and cited the

NAS conclusion that "not only are the basic scientific questions largely

unanswered, but in many cases we do not yet know enough to pose the key

questions."

The article mentioned the alternative solutions of "melting the

Arctic ice cap by covering it with black soot or diverting Arctic

rivers" but conceded these were not feasible. The Newsweek

article concluded by criticizing government leaders: "But the scientists

see few signs that government leaders anywhere are even prepared to

take the simple measures of stockpiling food or of introducing the

variables of climatic uncertainty into economic projections of future

food supplies...The longer the planners (politicians) delay, the more

difficult will they find it to cope with climatic change once the

results become grim reality." The article emphasized sensational and

largely unsourced consequences - "resulting famines could be

catastrophic", "drought and desolation," "the most devastating outbreak

of tornadoes ever recorded", "droughts, floods, extended dry spells,

long freezes, delayed monsoons," "impossible for starving peoples to

migrate," "the present decline has taken the planet about a sixth of the

way toward the Ice Age."

On October 23, 2006, Newsweek issued a correction, over 31

years after the original article, stating that it had been "so

spectacularly wrong about the near-term future" (though editor Jerry

Adler stated that "the story wasn't 'wrong' in the journalistic sense of

'inaccurate.'")

Other 1970s sources

Academic

analysis of the peer-reviewed studies published at that time shows that

most papers examining aspects of climate during the 1970s were either

neutral or showed a warming trend.

In 1977, a popular book on the topic was published, called The Weather Conspiracy: The Coming of the New Ice Age.

There were also a US TV show narrated by Leonard Nimoy in the 1977 In Search of... (TV series),

episode 27, season 2, titled, "The Coming Ice Age: An inquiry into

whether the dramatic weather changes in America's northern states mean

that a new ice age is approaching."

1979 WMO conference

Later in the decade, at a WMO conference in 1979, F K Hare reported:

- Fig 8 shows [...] 1938 the warmest year. They [temperatures] have since fallen by about 0.4 °C. At the end there is a suggestion that the fall ceased in about 1964, and may even have reversed.

- Figure 9 challenges the view that the fall of temperature has ceased [...] the weight of evidence clearly favors cooling to the present date [...] The striking point, however, is that interannual variability of world temperatures is much larger than the trend [...] it is difficult to detect a genuine trend [...]

- It is questionable, moreover, whether the trend is truly global. Calculated variations in the 5-year mean air temperature over the southern hemisphere chiefly with respect to land areas show that temperatures generally rose between 1943 and 1975. Since the 1960-64 period this rise has been strong [...] the scattered SH data fail to support a hypothesis of continued global cooling since 1938. [p 65]

Late 20th Century cooling predictions

1980s

Concerns about nuclear winter arose in the early 1980s from several reports. Similar speculations have appeared over effects due to catastrophes such as asteroid impacts and massive volcanic eruptions. In 1991, a prediction that massive oil well fires in Kuwait would cause significant effects on climate was incorrect.

1990s

In January 1999, contrarian Patrick Michaels

wrote a commentary offering to "take even money that the 10 years

ending on December 31, 2007, will show a statistically significant

global cooling trend in temperatures measured by satellite", on the

basis of his view that record temperatures in 1998 had been a blip.

Indeed, over that period, satellite-measured temperatures never again

approached their 1998 peak. Due to a sharp but temporary dip in

temperatures in 1999-2000, a least-squares linear regression fit to the

satellite temperature record showed little overall trend. The RSS

satellite temperature record showed a slight cooling trend, but the UAH satellite temperature record showed a slight warming trend.

In 2003, the Office of Net Assessment at the United States Department of Defense was commissioned to produce a study on the likely and potential effects of abrupt modern climate change should a shutdown of thermohaline circulation occur. The study, conducted under ONA head Andrew Marshall, modeled its prospective climate change on the 8.2 kiloyear event, precisely because it was the middle alternative between the Younger Dryas and the Little Ice Age. Scientists acknowledge that "abrupt climate change initiated by Greenland ice sheet melting is not a realistic scenario for the 21st century".

Present level of knowledge

Currently,

the concern that cooler temperatures would continue, and perhaps at a

faster rate, has been observed to be incorrect by the IPCC.

More has to be learned about climate, but the growing records have

shown that the cooling concerns of 1975 have not been borne out.

As for the prospects of the end of the current interglacial,

while the four most recent interglacials lasted about 10,000 years, the

interglacial before that lasted around 28,000 years. Milankovitch-type

calculations indicate that the present interglacial would probably

continue for tens of thousands of years naturally in the absence of

human perturbations.

Other estimates (Loutre and Berger, based on orbital calculations) put

the unperturbed length of the present interglacial at 50,000 years. Berger (EGU 2005 presentation) thinks that the present CO2 perturbation will last long enough to suppress the next glacial cycle entirely.This is entirely consistent with David Archer's and colleague's prediction who argue that the present level of CO

2 will suspend the next glacial period for the next 500,000 years and will be the longest duration and intensity of the projected interglacial period and are longer than have been seen in the last 2.6 million years.

2 will suspend the next glacial period for the next 500,000 years and will be the longest duration and intensity of the projected interglacial period and are longer than have been seen in the last 2.6 million years.

As the NAS report indicates, scientific knowledge regarding

climate change was more uncertain than it is today. At the time that

Rasool and Schneider wrote their 1971 paper, climatologists had not yet

recognized the significance of greenhouse gases other than water vapor

and carbon dioxide, such as methane, nitrous oxide, and chlorofluorocarbons.

Early in that decade, carbon dioxide was the only widely studied

human-influenced greenhouse gas. The attention drawn to atmospheric

gases in the 1970s stimulated many discoveries in subsequent decades. As

the temperature pattern changed, global cooling was of waning interest

by 1979.

The ice age fallacy

A common argument used to dispute the significance of human caused climate change,

which TIME Magazine calls the Ice Age Fallacy, is to allege that

scientists showed concerns about global cooling which did not

materialize, therefore there is no need to heed current scientific

concerns about climate change. In a 1998 article promoting the Oregon Petition, Fred Singer

argued that expert concerns about global warming should be dismissed on

the basis that what he called "the same hysterical fears" had

supposedly been expressed earlier about global cooling.

Illustrating this argument, for several years an image has been circulated of a Time magazine cover, supposedly dated 1977, showing a penguin above a cover story title "How to Survive the Coming Ice Age". In March 2013, The Mail on Sunday published an article by David Rose,

showing this same cover image, to support his claim that there was as

much concern in the 1970s about a "looming 'ice age'" as there was now

about global warming. After researching the authenticity of the magazine cover image, in July 2013, Bryan Walsh, a senior editor at Time, confirmed that the image was a hoax, modified from a 2007 cover story image for "The Global Warming Survival Guide".