The nature versus nurture debate involves whether human behavior is determined by the environment, either prenatal or during a person's life, or by a person's genes. The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English has been in use since at least the Elizabethan period and goes back to medieval French.

The combination of the two concepts as complementary is ancient (Greek: ἁπό φύσεως καὶ εὐτροφίας).

Nature is what we think of as pre-wiring and is influenced by genetic

inheritance and other biological factors. Nurture is generally taken as

the influence of external factors after conception e.g. the product of

exposure, experience and learning on an individual.

The phrase in its modern sense was popularized by the English Victorian polymath Francis Galton, the modern founder of eugenics and behavioral genetics, discussing the influence of heredity and environment on social advancement. Galton was influenced by the book On the Origin of Species written by his half-cousin, Charles Darwin.

The view that humans acquire all or almost all their behavioral traits from "nurture" was termed tabula rasa ("blank slate") by John Locke in 1690. A "blank slate view" in human developmental psychology assuming that human behavioral traits develop almost exclusively from environmental influences, was widely held during much of the 20th century (sometimes termed "blank-slatism"). The debate between "blank-slate" denial of the influence of heritability, and the view admitting both environmental and heritable traits, has often been cast in terms of nature versus nurture. These two conflicting approaches to human development were at the core of an ideological dispute over research agendas throughout the second half of the 20th century. As both "nature" and "nurture" factors were found to contribute substantially, often in an extricable manner, such views were seen as naive or outdated by most scholars of human development by the 2000s.

The strong dichotomy of nature versus nurture has thus been claimed to have limited relevance in some fields of research. Close feedback loops have been found in which "nature" and "nurture" influence one another constantly, as seen in self-domestication. In ecology and behavioral genetics, researchers think nurture has an essential influence on nature. Similarly in other fields, the dividing line between an inherited and an acquired trait becomes unclear, as in epigenetics or fetal development.

The view that humans acquire all or almost all their behavioral traits from "nurture" was termed tabula rasa ("blank slate") by John Locke in 1690. A "blank slate view" in human developmental psychology assuming that human behavioral traits develop almost exclusively from environmental influences, was widely held during much of the 20th century (sometimes termed "blank-slatism"). The debate between "blank-slate" denial of the influence of heritability, and the view admitting both environmental and heritable traits, has often been cast in terms of nature versus nurture. These two conflicting approaches to human development were at the core of an ideological dispute over research agendas throughout the second half of the 20th century. As both "nature" and "nurture" factors were found to contribute substantially, often in an extricable manner, such views were seen as naive or outdated by most scholars of human development by the 2000s.

The strong dichotomy of nature versus nurture has thus been claimed to have limited relevance in some fields of research. Close feedback loops have been found in which "nature" and "nurture" influence one another constantly, as seen in self-domestication. In ecology and behavioral genetics, researchers think nurture has an essential influence on nature. Similarly in other fields, the dividing line between an inherited and an acquired trait becomes unclear, as in epigenetics or fetal development.

History of the debate

John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) is often cited as the foundational document of the "blank slate" view. Locke was criticizing René Descartes's claim of an innate idea of God universal to humanity.

Locke's view was harshly criticized in his own time. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, complained that by denying the possibility of any innate ideas,

Locke "threw all order and virtue out of the world", leading to total moral relativism.

Locke's was not the predominant view in the 19th century, which on the contrary tended to focus on "instinct".

Leda Cosmides and John Tooby noted that William James (1842–1910) argued that humans have more instincts than animals, and that greater freedom of action is the result of having more psychological instincts, not fewer.

The question of "innate ideas" or "instincts" were of some importance in the discussion of free will in moral philosophy.

In 18th-century philosophy, this was cast in terms of "innate ideas"

establishing the presence of a universal virtue, prerequisite for

objective morals. In the 20th century, this argument was in a way

inverted, as some philosophers now argued that the evolutionary origins

of human behavioral traits forces us to concede that there is no

foundation for ethics (J. L. Mackie), while others treat ethics as a field in complete isolation from evolutionary considerations (Thomas Nagel).

In the early 20th century, there was an increased interest in the

role of the environment, as a reaction to the strong focus on pure

heredity in the wake of the triumphal success of Darwin's theory of

evolution.

During this time, the social sciences developed as the project of studying the influence of culture in clean isolation from questions related to "biology".

Franz Boas's The Mind of Primitive Man

(1911) established a program that would dominate American anthropology

for the next fifteen years. In this study he established that in any

given population, biology, language, material and symbolic culture, are

autonomous; that each is an equally important dimension of human nature,

but that no one of these dimensions is reducible to another.

The tool of twin studies was developed as a research design intended to exclude all confounders based on inherited behavioral traits.

Such studies are designed to decompose the variability of a given trait

in a given population into a genetic and an environmental component.

John B. Watson in the 1920s and 1930s established the school of purist behaviorism

that would become dominant over the following decades. Watson is often

said to have been convinced of the complete dominance of cultural

influence over anything that heredity might contribute, based on the

following quote which is frequently repeated without context:

- Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select – doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors. I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years (Behaviorism, 1930, p. 82).

The last sentence of the above quote is frequently omitted, leading to confusion about Watson's position.

During the 1940s to 1960s, Ashley Montagu was a notable proponent of this purist form of behaviorism which allowed no contribution from heredity whatsoever:

- "Man is man because he has no instincts, because everything he is and has become he has learned, acquired, from his culture ... with the exception of the instinctoid reactions in infants to sudden withdrawals of support and to sudden loud noises, the human being is entirely instinctless.

In 1951, Calvin Hall suggested that the dichotomy opposing nature to nurture is ultimately fruitless.

Robert Ardrey in the 1960s argued for innate attributes of human nature, especially concerning territoriality, in the widely read African Genesis (1961) and The Territorial Imperative. Desmond Morris in The Naked Ape (1967) expressed similar views.

Organised opposition to Montagu's kind of purist "blank-slatism" began to pick up in the 1970s, notably led by E. O. Wilson (On Human Nature

1979).

Twin studies established that there was, in many cases, a significant

heritable component.

These results did not in any way point to overwhelming contribution of

heritable factors, with heritability typically ranging around 40% to

50%, so that the controversy may not be cast in terms of purist

behaviorism vs. purist nativism. Rather, it was purist behaviorism which

was gradually replaced by the now-predominant view that both kinds of

factors usually contribute to a given trait, anecdotally phrased by Donald Hebb

as an answer to the question "which, nature or nurture, contributes

more to personality?" by asking in response, "Which contributes more to

the area of a rectangle, its length or its width?"

In a comparable avenue of research, anthropologist Donald Brown in the

1980s surveyed hundreds of anthropological studies from around the world

and collected a set of cultural universals.

He identified approximately 150 such features, coming to the conclusion

there is indeed a "universal human nature", and that these features

point to what that universal human nature is.

At the height of the controversy, during the 1970s to 1980s, the debate was highly ideologised. In Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature (1984), Richard Lewontin, Steven Rose and Leon Kamin criticise "genetic determinism" from a Marxist framework, arguing that "Science is the ultimate legitimator of bourgeois ideology ... If biological determinism

is a weapon in the struggle between classes, then the universities are

weapons factories, and their teaching and research faculties are the

engineers, designers, and production workers." The debate thus shifted

away from whether heritable traits exist to whether it was politically

or ethically permissible to admit their existence. The authors deny

this, requesting that evolutionary inclinations be discarded in ethical

and political discussions regardless of whether they exist or not.

Heritability studies became much easier to perform, and hence

much more numerous, with the advances of genetic studies during the

1990s. By the late 1990s, an overwhelming amount of evidence had

accumulated that amounts to a refutation of the extreme forms of

"blank-slatism" advocated by Watson or Montagu.

This revised state of affairs was summarized in books aimed at a popular audience from the late 1990s. In The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do (1998), Judith Rich Harris was heralded by Steven Pinker as a book that "will come to be seen as a turning point in the history of psychology".

but Harris was criticized for exaggerating the point of "parental

upbringing seems to matter less than previously thought" to the

implication that "parents do not matter".

The situation as it presented itself by the end of the 20th century was summarized in The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2002) by Steven Pinker.

The book became a best-seller, and was instrumental in bringing to the

attention of a wider public the paradigm shift away from the

behaviourist purism of the 1940s to 1970s that had taken place over the

preceding decades. Pinker portrays the adherence to pure blank-slatism

as an ideological dogma linked to two other dogmas found in the dominant view of human nature in the 20th century, which he termed "noble savage" (in the sense that people are born good and corrupted by bad influence) and

"ghost in the machine"

(in the sense that there is a human soul capable of moral choices

completely detached from biology). Pinker argues that all three dogmas

were held onto for an extended period even in the face of evidence

because they were seen as desirable in the sense that if any

human trait is purely conditioned by culture, any undesired trait (such

as crime or aggression) may be engineered away by purely cultural

(political means). Pinker focuses on reasons he assumes were responsible

for unduly repressing evidence to the contrary, notably the fear of

(imagined or projected) political or ideological consequences.

Heritability estimates

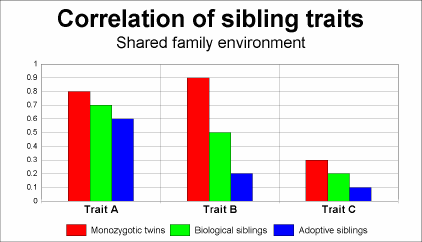

This

chart illustrates three patterns one might see when studying the

influence of genes and environment on traits in individuals. Trait A

shows a high sibling correlation, but little heritability (i.e. high

shared environmental variance c2; low heritability h2).

Trait B shows a high heritability since correlation of trait rises

sharply with the degree of genetic similarity. Trait C shows low

heritability, but also low correlations generally; this means Trait C

has a high nonshared environmental variance e2. In

other words, the degree to which individuals display Trait C has little

to do with either genes or broadly predictable environmental

factors—roughly, the outcome approaches random for an individual. Notice

also that even identical twins raised in a common family rarely show

100% trait correlation.

It is important to note that the term heritability refers only

to the degree of genetic variation between people on a trait. It does

not refer to the degree to which a trait of a particular individual is

due to environmental or genetic factors. The traits of an individual are

always a complex interweaving of both.

For an individual, even strongly genetically influenced, or "obligate"

traits, such as eye color, assume the inputs of a typical environment

during ontogenetic development (e.g., certain ranges of temperatures,

oxygen levels, etc.).

In contrast, the "heritability index" statistically quantifies the extent to which variation between individuals

on a trait is due to variation in the genes those individuals carry. In

animals where breeding and environments can be controlled

experimentally, heritability can be determined relatively easily. Such

experiments would be unethical for human research. This problem can be

overcome by finding existing populations of humans that reflect the

experimental setting the researcher wishes to create.

One way to determine the contribution of genes and environment to a trait is to study twins. In one kind of study, identical twins

reared apart are compared to randomly selected pairs of people. The

twins share identical genes, but different family environments. In

another kind of twin study, identical twins reared together (who share

family environment and genes) are compared to fraternal twins

reared together (who also share family environment but only share half

their genes). Another condition that permits the disassociation of genes

and environment is adoption. In one kind of adoption study,

biological siblings reared together (who share the same family

environment and half their genes) are compared to adoptive siblings (who

share their family environment but none of their genes).

In many cases, it has been found that genes make a substantial

contribution, including psychological traits such as intelligence and

personality.

Yet heritability may differ in other circumstances, for instance

environmental deprivation. Examples of low, medium, and high

heritability traits include:

| Low heritability | Medium heritability | High heritability |

|---|---|---|

| Specific language | Weight | Blood type |

| Specific religion | Religiosity | Eye color |

Twin and adoption studies have their methodological limits. For

example, both are limited to the range of environments and genes which

they sample. Almost all of these studies are conducted in Western,

first-world countries, and therefore cannot be extrapolated globally to

include poorer, non-western populations. Additionally, both types of

studies depend on particular assumptions, such as the equal environments assumption in the case of twin studies, and the lack of pre-adoptive effects in the case of adoption studies.

Since the definition of "nature" in this context is tied to

"heritability", the definition of "nurture" has necessarily become very

wide, including any type of causality that is not heritable. The term

has thus moved away from its original connotation of "cultural

influences" to include all effects of the environment, including;

indeed, a substantial source of environmental input to human nature may arise from stochastic variations in prenatal development and is thus in no sense of the term "cultural".

Interaction of genes and environment

| “ | Many properties of the brain are genetically organized, and don't depend on information coming in from the senses. | ” |

| — Steven Pinker | ||

Heritability refers to the origins of differences between people.

Individual development, even of highly heritable traits, such as eye

color, depends on a range of environmental factors, from the other genes

in the organism, to physical variables such as temperature, oxygen

levels etc. during its development or ontogenesis.

The variability of trait can be meaningfully spoken of as being

due in certain proportions to genetic differences ("nature"), or

environments ("nurture"). For highly penetrant Mendelian genetic disorders such as Huntington's disease

virtually all the incidence of the disease is due to genetic

differences. Huntington's animal models live much longer or shorter

lives depending on how they are cared for.

At the other extreme, traits such as native language

are environmentally determined: linguists have found that any child (if

capable of learning a language at all) can learn any human language

with equal facility.

With virtually all biological and psychological traits, however, genes

and environment work in concert, communicating back and forth to create

the individual.

At a molecular level, genes interact with signals from other

genes and from the environment. While there are many thousands of

single-gene-locus traits, so-called complex traits

are due to the additive effects of many (often hundreds) of small gene

effects. A good example of this is height, where variance appears to be

spread across many hundreds of loci.

Extreme genetic or environmental conditions can predominate in

rare circumstances—if a child is born mute due to a genetic mutation, it

will not learn to speak any language regardless of the environment;

similarly, someone who is practically certain to eventually develop

Huntington's disease according to their genotype may die in an unrelated

accident (an environmental event) long before the disease will manifest

itself.

The "two buckets" view of heritability.

More realistic "homogenous mudpie" view of heritability.

Steven Pinker likewise described several examples:

- ...concrete behavioral traits that patently depend on content provided by the home or culture—which language one speaks, which religion one practices, which political party one supports—are not heritable at all. But traits that reflect the underlying talents and temperaments—how proficient with language a person is, how religious, how liberal or conservative—are partially heritable.

When traits are determined by a complex interaction of genotype and environment it is possible to measure the heritability

of a trait within a population. However, many non-scientists who

encounter a report of a trait having a certain percentage heritability

imagine non-interactional, additive contributions of genes and

environment to the trait. As an analogy, some laypeople may think of the

degree of a trait being made up of two "buckets," genes and

environment, each able to hold a certain capacity of the trait. But even

for intermediate heritabilities, a trait is always shaped by both

genetic dispositions and the environments in which people develop,

merely with greater and lesser plasticities associated with these

heritability measures.

Heritability measures always refer to the degree of variation between individuals in a population.

That is, as these statistics cannot be applied at the level of the

individual, it would be incorrect to say that while the heritability

index of personality is about 0.6, 60% of one's personality is obtained

from one's parents and 40% from the environment. To help to understand

this, imagine that all humans were genetic clones. The heritability

index for all traits would be zero (all variability between clonal

individuals must be due to environmental factors). And, contrary to

erroneous interpretations of the heritability index, as societies become

more egalitarian (everyone has more similar experiences) the

heritability index goes up (as environments become more similar,

variability between individuals is due more to genetic factors).

One should also take into account the fact that the variables of

heritability and environmentality are not precise and vary within a

chosen population and across cultures. It would be more accurate to

state that the degree of heritability and environmentality is measured

in its reference to a particular phenotype in a chosen group of a

population in a given period of time. The accuracy of the calculations

is further hindered by the number of coefficients taken into

consideration, age being one such variable. The display of the influence

of heritability and environmentality differs drastically across age

groups: the older the studied age is, the more noticeable the

heritability factor becomes, the younger the test subjects are, the more

likely it is to show signs of strong influence of the environmental

factors.

Some have pointed out that environmental inputs affect the expression of genes. This is one explanation of how environment can influence the extent to which a genetic disposition will actually manifest. The interactions of genes with environment, called gene–environment interactions,

are another component of the nature–nurture debate. A classic example

of gene–environment interaction is the ability of a diet low in the

amino acid phenylalanine to partially suppress the genetic disease phenylketonuria. Yet another complication to the nature–nurture debate is the existence of gene–environment correlations.

These correlations indicate that individuals with certain genotypes are

more likely to find themselves in certain environments. Thus, it

appears that genes can shape (the selection or creation of)

environments. Even using experiments like those described above, it can

be very difficult to determine convincingly the relative contribution of

genes and environment.

A study conducted by T. J. Bouchard, Jr. showed data that has

been evidence for the importance of genes when testing middle-aged twins

reared together and reared apart. The results shown have been important

evidence against the importance of environment when determining,

happiness, for example. In the Minnesota study of twins reared apart, it

was actually found that there was higher correlation for monozygotic

twins reared apart (0.52)than monozygotic twins reared together (0.44).

Also, highlighting the importance of genes, these correlations found

much higher correlation among monozygotic than dizygotic twins that had a

correlation of 0.08 when reared together and −0.02 when reared apart.

Social pre-wiring

The social pre-wiring hypothesis refers to the ontogeny of social interaction. Also informally referred to as, "wired to be social." The theory questions whether there is a propensity to socially oriented action already present before birth. Research in the theory concludes that newborns are born into the world with a unique genetic wiring to be social.

Circumstantial evidence supporting the social pre-wiring

hypothesis can be revealed when examining newborns' behavior. Newborns,

not even hours after birth, have been found to display a preparedness

for social interaction.

This preparedness is expressed in ways such as their imitation of

facial gestures. This observed behavior cannot be contributed to any

current form of socialization or social construction. Rather, newborns most likely inherit to some extent social behavior and identity through genetics.

Principal evidence of this theory is uncovered by examining twin pregnancies. The main argument is, if there are social behaviors that are inherited and developed before birth, then one should expect twin fetuses to engage in some form of social interaction

before they are born. Thus, ten fetuses were analyzed over a period of

time using ultrasound techniques. Using kinematic analysis, the results

of the experiment were that the twin fetuses would interact with each

other for longer periods and more often as the pregnancies went on.

Researchers were able to conclude that the performance of movements

between the co-twins were not accidental but specifically aimed.

The social pre-wiring hypothesis was proved correct, "The central advance of this study is the demonstration that 'social actions' are already performed in the second trimester of gestation. Starting from the 14th week of gestation

twin foetuses plan and execute movements specifically aimed at the

co-twin. These findings force us to predate the emergence of social behavior:

when the context enables it, as in the case of twin fetuses,

other-directed actions are not only possible but predominant over

self-directed actions.".

Obligate vs. facultative adaptations

Traits

may be considered to be adaptations (such as the umbilical cord),

byproducts of adaptations (the belly button) or due to random variation

(convex or concave belly button shape).

An alternative to contrasting nature and nurture focuses on "obligate vs. facultative" adaptations.

Adaptations may be generally more obligate (robust in the face of

typical environmental variation) or more facultative (sensitive to

typical environmental variation). For example, the rewarding sweet

taste of sugar and the pain of bodily injury are obligate psychological

adaptations—typical environmental variability during development does

not much affect their operation. On the other hand, facultative adaptations are somewhat like "if-then" statements. An example of a facultative psychological adaptation may be adult attachment style.

The attachment style of adults, (for example, a "secure attachment

style," the propensity to develop close, trusting bonds with others) is

proposed to be conditional on whether an individual's early childhood

caregivers could be trusted to provide reliable assistance and

attention. An example of a facultative physiological adaptation is

tanning of skin on exposure to sunlight (to prevent skin damage).

Facultative social adaptation have also been proposed. For example,

whether a society is warlike or peaceful has been proposed to be

conditional on how much collective threat that society is experiencing .

Advanced techniques

Quantitative studies of heritable traits throw light on the question.

Developmental genetic analysis examines the effects of genes over

the course of a human lifespan. Early studies of intelligence, which

mostly examined young children, found that heritability

measured 40–50%. Subsequent developmental genetic analyses found that

variance attributable to additive environmental effects is less apparent

in older individuals, with estimated heritability of IQ increasing in adulthood.

Multivariate genetic analysis examines the genetic contribution

to several traits that vary together. For example, multivariate genetic

analysis has demonstrated that the genetic determinants of all specific

cognitive abilities (e.g., memory, spatial reasoning, processing speed)

overlap greatly, such that the genes associated with any specific

cognitive ability will affect all others. Similarly, multivariate

genetic analysis has found that genes that affect scholastic achievement

completely overlap with the genes that affect cognitive ability.

Extremes analysis examines the link between normal and

pathological traits. For example, it is hypothesized that a given

behavioral disorder may represent an extreme of a continuous

distribution of a normal behavior and hence an extreme of a continuous

distribution of genetic and environmental variation. Depression,

phobias, and reading disabilities have been examined in this context.

For a few highly heritable traits, studies have identified loci

associated with variance in that trait, for instance in some individuals

with schizophrenia.

Entrepreneurship

Through

studies of identical twins separated at birth, one-third of their

creative thinking abilities come from genetics and two-thirds come from

learning. Research suggests that between 37 and 42 percent of the explained variance can be attributed to genetic factors. The learning primarily comes in the form of human capital transfers of entrepreneurial skills through parental role modeling.

Other findings agree that the key to innovative entrepreneurial success

comes from environmental factors and working “10,000 hours” to gain

mastery in entrepreneurial skills.

Heritability of intelligence

Evidence from behavioral genetic research suggests that family environmental factors may have an effect upon childhood IQ, accounting for up to a quarter of the variance. The American Psychological Association's report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns"

(1995) states that there is no doubt that normal child development

requires a certain minimum level of responsible care. Here, environment

is playing a role in what is believed to be fully genetic (intelligence)

but it was found that severely deprived, neglectful, or abusive

environments have highly negative effects on many aspects of children's

intellect development. Beyond that minimum, however, the role of family

experience is in serious dispute. On the other hand, by late adolescence

this correlation disappears, such that adoptive siblings no longer have

similar IQ scores.

Moreover, adoption studies indicate that, by adulthood, adoptive

siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near

zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies

reinforce this pattern: monozygotic (identical) twins raised separately

are highly similar in IQ (0.74), more so than dizygotic (fraternal)

twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adoptive siblings (~0.0). Recent adoption studies also found that supportive parents can have a positive effect on the development of their children.

Personality traits

Personality is a frequently cited example of a heritable trait that has been studied in twins and adoptees using behavioral genetic

study designs. The most famous categorical organization of heritable

personality traits were created by Goldberg (1990) in which he had

college students rate their personalities on 1400 dimensions to begin,

and then narrowed these down into "The Big Five"

factors of personality—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion,

agreeableness, and neuroticism. The close genetic relationship between

positive personality traits and, for example, our happiness traits are

the mirror images of comorbidity in psychopathology. These personality

factors were consistent across cultures, and many studies have also

tested the heritability of these traits.

Identical twins reared apart are far more similar in personality

than randomly selected pairs of people. Likewise, identical twins are

more similar than fraternal twins. Also, biological siblings are more

similar in personality than adoptive siblings. Each observation suggests

that personality is heritable to a certain extent. A supporting article

had focused on the heritability of personality (which is estimated to

be around 50% for subjective well-being) in which a study was conducted

using a representative sample of 973 twin pairs to test the heritable

differences in subjective well-being which were found to be fully

accounted for by the genetic model of the Five-Factor Model’s

personality domains. However, these same study designs allow for the examination of environment as well as genes.

Adoption studies also directly measure the strength of shared

family effects. Adopted siblings share only family environment. Most

adoption studies indicate that by adulthood the personalities of adopted

siblings are little or no more similar than random pairs of strangers.

This would mean that shared family effects on personality are zero by

adulthood.

In the case of personality traits, non-shared environmental

effects are often found to out-weigh shared environmental effects. That

is, environmental effects that are typically thought to be life-shaping

(such as family life) may have less of an impact than non-shared

effects, which are harder to identify. One possible source of non-shared

effects is the environment of pre-natal development. Random variations

in the genetic program of development may be a substantial source of

non-shared environment. These results suggest that "nurture" may not be

the predominant factor in "environment". Environment and our situations,

do in fact impact our lives, but not the way in which we would

typically react to these environmental factors. We are preset with

personality traits that are the basis for how we would react to

situations. An example would be how extraverted prisoners become less

happy than introverted prisoners and would react to their incarceration

more negatively due to their preset extraverted personality.

Behavioral genes are somewhat proven to exist when we take a look at

fraternal twins. When fraternal twins are reared apart, they show the

same similarities in behavior and response as if they have been reared

together.

Genetics

Genomics

The relationship between personality and people's own well-being is

influenced and mediated by genes (Weiss, Bates, & Luciano, 2008).

There has been found to be a stable set point for happiness that is

characteristic of the individual (largely determined by the individual's

genes). Happiness fluctuates around that setpoint (again, genetically

determined) based on whether good things or bad things are happening to

us ("nurture"), but only fluctuates in small magnitude in a normal

human. The midpoint of these fluctuations is determined by the "great

genetic lottery" that people are born with, which leads them to conclude

that how happy they may feel at the moment or over time is simply due

to the luck of the draw, or gene. This fluctuation was also not due to

educational attainment, which only accounted for less than 2% of the

variance in well-being for women, and less than 1% of the variance for

men.

They consider that the individualities measured together with

personality tests remain steady throughout an individual’s lifespan.

They further believe that human beings may refine their forms or

personality but can never change them entirely. Darwin's Theory of

Evolution steered naturalists such as George Williams and William

Hamilton to the concept of personality evolution. They suggested that

physical organs and also personality is a product of natural selection.

With the advent of genomic sequencing,

it has become possible to search for and identify specific gene

polymorphisms that affect traits such as IQ and personality. These

techniques work by tracking the association of differences in a trait of

interest with differences in specific molecular markers or functional

variants. An example of a visible human trait for which the precise

genetic basis of differences are relatively well known is eye color.

For traits with many genes affecting the outcome, a smaller portion of

the variance is currently understood: For instance for height known gene

variants account for around 5–10% of height variance at present.

When discussing the significant role of genetic heritability in relation

to one's level of happiness, it has been found that from 44% to 52% of

the variance in one's well-being is associated with genetic variation.

Based on the retest of smaller samples of twins studies after 4,5, and

10 years, it is estimated that the heritability of the genetic stable

component of subjective well-being approaches 80%.

Other studies that have found that genes are a large influence in the

variance found in happiness measures, exactly around 35–50%.

In contrast to views developed in 1960s that gender identity is

primarily learned (which led to policy-based surgical sex changed in

children such as David Reimer), genomics has provided solid evidence that both sex and gender identities are primarily influenced by genes:

It is now clear that genes are vastly more influential than virtually any other force in shaping sex identity and gender identity…[T]he growing consensus in medicine is that…children should be assigned to their chromosomal (i.e., genetic) sex regardless of anatomical variations and differences—with the option of switching, if desired, later in life.

— Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Gene: An Intimate History

Linkage and association studies

In

their attempts to locate the genes responsible for configuring certain

phenotypes, researches resort to two different techniques.

Linkage study facilitates the process of determining a specific location

in which a gene of interest is located. This methodology is applied

only among individuals that are related and does not serve to pinpoint

specific genes. It does, however, narrow down the area of search, making

it easier to locate one or several genes in the genome which constitute

a specific trait.

Association studies, on the other hand, are more hypothetic and

seek to verify whether a particular genetic variable really influences

the phenotype of interest. In association studies it is more common to

use case-control approach, comparing the subject with relatively higher

or lower hereditary determinants with the control subject.