Sociobiology is a field of biology that aims to examine and explain social behavior in terms of evolution. It draws from disciplines including ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics. Within the study of human societies, sociobiology is closely allied to Darwinian anthropology, human behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology.

Sociobiology investigates social behaviors such as mating patterns, territorial fights, pack hunting, and the hive society of social insects. It argues that just as selection pressure led to animals evolving useful ways of interacting with the natural environment, so also it led to the genetic evolution of advantageous social behavior.

While the term "sociobiology" originated at least as early as the 1940s, the concept did not gain major recognition until the publication of E. O. Wilson's book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in 1975. The new field quickly became the subject of controversy. Critics, led by Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, argued that genes played a role in human behavior, but that traits such as aggressiveness could be explained by social environment rather than by biology. Sociobiologists responded by pointing to the complex relationship between nature and nurture.

Definition

E. O. Wilson defined sociobiology as "the extension of population biology and evolutionary theory to social organization".

Sociobiology is based on the premise that some behaviors (social

and individual) are at least partly inherited and can be affected by natural selection.

It begins with the idea that behaviors have evolved over time, similar

to the way that physical traits are thought to have evolved. It predicts

that animals will act in ways that have proven to be evolutionarily

successful over time. This can, among other things, result in the

formation of complex social processes conducive to evolutionary fitness.

The discipline seeks to explain behavior as a product of natural

selection. Behavior is therefore seen as an effort to preserve one's

genes in the population. Inherent in sociobiological reasoning is the

idea that certain genes or gene combinations that influence particular

behavioral traits can be inherited from generation to generation.

For example, newly dominant male lions often kill cubs in the pride that they did not sire. This behavior is adaptive because killing the cubs eliminates competition

for their own offspring and causes the nursing females to come into

heat faster, thus allowing more of his genes to enter into the

population. Sociobiologists would view this instinctual cub-killing

behavior as being inherited through the genes of successfully

reproducing male lions, whereas non-killing behavior may have died out

as those lions were less successful in reproducing.

History

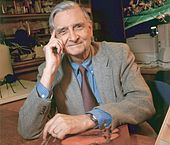

E. O. Wilson, a central figure in the history of sociobiology, from the publication in 1975 of his book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis

The philosopher of biology Daniel Dennett suggested that the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes was the first sociobiologist, arguing that in his 1651 book Leviathan Hobbes had explained the origins of morals in human society from an amoral sociobiological perspective.

The geneticist of animal behavior John Paul Scott coined the word sociobiology

at a 1948 conference on genetics and social behavior which called for a

conjoint development of field and laboratory studies in animal behavior

research.

With John Paul Scott's organizational efforts, a "Section of Animal

Behavior and Sociobiology" of the ESA was created in 1956, which became a

Division of Animal Behavior of the American Society of Zoology in 1958.

In 1956, E. O. Wilson

came in contact this emerging sociobiology through his PhD student

Stuart A. Altmann, who had been in close relation with the participants

to the 1948 conference. Altmann developed his own brand of sociobiology

to study the social behavior of rhesus macaques, using statistics, and

was hired as a "sociobiologist" at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research

Center in 1965.

Wilson's sociobiology is different from John Paul Scott's

or Altmann's, insofar as he drew on mathematical models of social

behavior centered on the maximization of the genetic fitness by W. D. Hamilton, Robert Trivers, John Maynard Smith, and George R. Price.

The three sociobiologies by Scott, Altmann and Wilson have in common to

place naturalist studies at the core of the research on animal social

behavior and by drawing alliances with emerging research methodologies,

at a time when "biology in the field" was threatened to be made

old-fashioned by "modern" practices of science (laboratory studies,

mathematical biology, molecular biology).

Once a specialist term, "sociobiology" became widely known in 1975 when Wilson published his book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis,

which sparked an intense controversy. Since then "sociobiology" has

largely been equated with Wilson's vision. The book pioneered and

popularized the attempt to explain the evolutionary mechanics behind

social behaviors such as altruism, aggression, and nurturance, primarily in ants (Wilson's own research specialty) and other Hymenoptera,

but also in other animals. However, the influence of evolution on

behavior has been of interest to biologists and philosophers since soon

after the discovery of evolution itself. Peter Kropotkin's Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution,

written in the early 1890s, is a popular example. The final chapter of

the book is devoted to sociobiological explanations of human behavior,

and Wilson later wrote a Pulitzer Prize winning book, On Human Nature, that addressed human behavior specifically.

Edward H. Hagen writes in The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology

that sociobiology is, despite the public controversy regarding the

applications to humans, "one of the scientific triumphs of the twentieth

century." "Sociobiology is now part of the core research and curriculum

of virtually all biology departments, and it is a foundation of the

work of almost all field biologists" Sociobiological research on

nonhuman organisms has increased dramatically and continuously in the

world's top scientific journals such as Nature and Science. The more general term behavioral ecology is commonly substituted for the term sociobiology in order to avoid the public controversy.

Theory

Sociobiologists maintain that human behavior,

as well as nonhuman animal behavior, can be partly explained as the

outcome of natural selection. They contend that in order to fully

understand behavior, it must be analyzed in terms of evolutionary

considerations.

Natural selection

is fundamental to evolutionary theory. Variants of hereditary traits

which increase an organism's ability to survive and reproduce will be

more greatly represented in subsequent generations, i.e., they will be

"selected for". Thus, inherited behavioral mechanisms that allowed an organism

a greater chance of surviving and/or reproducing in the past are more

likely to survive in present organisms. That inherited adaptive

behaviors are present in nonhuman animal species has been multiply demonstrated by biologists, and it has become a foundation of evolutionary biology.

However, there is continued resistance by some researchers over the

application of evolutionary models to humans, particularly from within

the social sciences, where culture has long been assumed to be the

predominant driver of behavior.

Nikolaas Tinbergen, whose work influenced sociobiology

Sociobiology is based upon two fundamental premises:

- Certain behavioral traits are inherited,

- Inherited behavioral traits have been honed by natural selection. Therefore, these traits were probably "adaptive" in the environment in which the species evolved.

Sociobiology uses Nikolaas Tinbergen's four categories of questions

and explanations of animal behavior. Two categories are at the species

level; two, at the individual level. The species-level categories (often

called "ultimate explanations") are

- the function (i.e., adaptation) that a behavior serves and

- the evolutionary process (i.e., phylogeny) that resulted in this functionality.

The individual-level categories (often called "proximate explanations") are

- the development of the individual (i.e., ontogeny) and

- the proximate mechanism (e.g., brain anatomy and hormones).

Sociobiologists are interested in how behavior can be explained

logically as a result of selective pressures in the history of a

species. Thus, they are often interested in instinctive, or intuitive

behavior, and in explaining the similarities, rather than the

differences, between cultures. For example, mothers within many species

of mammals – including humans – are very protective of their offspring.

Sociobiologists reason that this protective behavior likely evolved

over time because it helped the offspring of the individuals which had

the characteristic to survive. This parental protection would increase

in frequency in the population. The social behavior is believed to have

evolved in a fashion similar to other types of non-behavioral adaptations, such as a coat of fur, or the sense of smell.

Individual genetic advantage fails to explain certain social

behaviors as a result of gene-centred selection. E.O. Wilson argued that

evolution may also act upon groups. The mechanisms responsible for group selection employ paradigms and population statistics borrowed from evolutionary game theory.

Altruism is defined as "a concern for the welfare of others". If

altruism is genetically determined, then altruistic individuals must

reproduce their own altruistic genetic traits for altruism to survive,

but when altruists lavish their resources on non-altruists at the

expense of their own kind, the altruists tend to die out and the others

tend to increase. An extreme example is a soldier losing his life trying

to help a fellow soldier. This example raises the question of how

altruistic genes can be passed on if this soldier dies without having

any children.

Within sociobiology, a social behavior is first explained as a sociobiological hypothesis by finding an evolutionarily stable strategy

that matches the observed behavior. Stability of a strategy can be

difficult to prove, but usually, it will predict gene frequencies. The

hypothesis can be supported by establishing a correlation between the

gene frequencies predicted by the strategy, and those expressed in a

population.

Altruism between social insects

and littermates has been explained in such a way. Altruistic behavior,

behavior that increases the reproductive fitness of others at the

apparent expense of the altruist, in some animals has been correlated to the degree of genome shared between altruistic individuals. A quantitative description of infanticide by male harem-mating animals when the alpha male is displaced as well as rodent

female infanticide and fetal resorption are active areas of study. In

general, females with more bearing opportunities may value offspring

less, and may also arrange bearing opportunities to maximize the food and protection from mates.

An important concept in sociobiology is that temperament traits exist in an ecological balance. Just as an expansion of a sheep population might encourage the expansion of a wolf

population, an expansion of altruistic traits within a gene pool may

also encourage increasing numbers of individuals with dependent traits.

Studies of human behavior genetics have generally found behavioral traits such as creativity, extroversion, aggressiveness, and IQ have high heritability.

The researchers who carry out those studies are careful to point out

that heritability does not constrain the influence that environmental or

cultural factors may have on those traits.

Criminality

is actively under study, but extremely controversial. There are

arguments that in some environments criminal behavior might be adaptive. The novelist Elias Canetti also has noted applications of sociobiological theory to cultural practices such as slavery and autocracy.

Support for premise

Genetic mouse mutants illustrate the power that genes exert on behaviour. For example, the transcription factor FEV (aka Pet1), through its role in maintaining the serotonergic system in the brain, is required for normal aggressive and anxiety-like behavior.

Thus, when FEV is genetically deleted from the mouse genome, male mice

will instantly attack other males, whereas their wild-type counterparts

take significantly longer to initiate violent behaviour. In addition,

FEV has been shown to be required for correct maternal behaviour in

mice, such that offspring of mothers without the FEV factor do not

survive unless cross-fostered to other wild-type female mice.

A genetic basis for instinctive behavioral traits among

non-human species, such as in the above example, is commonly accepted

among many biologists; however, attempting to use a genetic basis to

explain complex behaviors in human societies has remained extremely

controversial.

Reception

Steven Pinker argues that critics have been overly swayed by politics and a fear of biological determinism, accusing among others Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin of being "radical scientists", whose stance on human nature is influenced by politics rather than science, while Lewontin, Steven Rose and Leon Kamin who drew a distinction between the politics and history of an idea and its scientific validity argue that sociobiology fails on scientific grounds. Gould grouped sociobiology with eugenics, criticizing both in his book The Mismeasure of Man.

Noam Chomsky has expressed views on sociobiology on several occasions. During a 1976 meeting of the Sociobiology Study Group, as reported by Ullica Segerstråle, Chomsky argued for the importance of a sociobiologically informed notion of human nature. Chomsky argued that human beings are biological organisms and ought to be studied as such, with his criticism of the "blank slate"

doctrine in the social sciences (which would inspire a great deal of

Steven Pinker's and others' work in evolutionary psychology), in his

1975 Reflections on Language. Chomsky further hinted at the possible reconciliation of his anarchist political views and sociobiology in a discussion of Peter Kropotkin's Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution,

which focused more on altruism than aggression, suggesting that

anarchist societies were feasible because of an innate human tendency to

cooperate.

Wilson has claimed that he had never meant to imply what ought to be, only what is the case. However, some critics have argued that the language of sociobiology readily slips from "is" to "ought", an instance of the naturalistic fallacy. Pinker has argued that opposition to stances considered anti-social, such as ethnic nepotism, is based on moral assumptions, meaning that such opposition is not falsifiable by scientific advances. The history of this debate, and others related to it, are covered in detail by Cronin (1993), Segerstråle (2000), and Alcock (2001).