What does it take for a person to persist from moment to moment—for the same person to exist at different moments?

In philosophy, the matter of personal identity

deals with such questions as, "What makes it true that a person at one

time is the same thing as a person at another time?" or "What kinds of

things are we persons?" Generally, personal identity is the unique numerical identity of a person in the course of time.

That is, the necessary and sufficient conditions under which a person

at one time and a person at another time can be said to be the same person, persisting through time.

In contemporary metaphysics, the matter of personal identity is referred to as the diachronic problem of personal identity. The synchronic problem concerns the question of what features and traits characterize a person at a given time. In continental philosophy and in analytic philosophy,

enquiry to the nature of Identity is common. Continental philosophy

deals with conceptually maintaining identity when confronted by

different philosophic propositions, postulates, and presuppositions about the world and its nature.

Theories

Continuity of substance

Bodily substance

One concept of personal persistence over time is simply to have continuous bodily existence. However, as the Ship of Theseus

problem illustrates, even for inanimate objects there are difficulties

in determining whether one physical body at one time is the same thing

as a physical body at another time. With humans, over time our bodies

age and grow, losing and gaining matter, and over sufficient years will

not consist of most of the matter they once consisted of. It is thus

problematic to ground persistence of personal identity over time in the

continuous existence of our bodies. Nevertheless, this approach has its

supporters which define humans as a biological organism and asserts the proposition that a psychological relation is not necessary for personal continuity. This personal identity ontology assumes the relational theory of life-sustaining processes instead of bodily continuity.

Derek Parfit's teletransportation problem is designed to bring out intuitions about corporeal continuity. This thought experiment discusses cases in which a person is teleported

from Earth to Mars. Ultimately, the inability to specify where on a

spectrum does the transmitted person stop being identical to the initial

person on Earth appears to show that having a numerically identical

physical body is not the criterion for personal identity

Mental substance

In another concept of mind, the set of cognitive faculties are considered to consist of an immaterial substance, separate from and independent of the body. If a person is then identified with their mind, rather than their body—if a person is considered to be

their mind—and their mind is such a non-physical substance, then

personal identity over time may be grounded in the persistence of this

non-physical substance, despite the continuous change in the substance

of the body it is associated with. The mind-body problem concerns the explanation of the relationship, if any, that exists between minds, or mental processes,

and bodily states or processes. One of the aims of philosophers who

work in this area is to explain how a non-material mind can influence a

material body and vice versa.

However, this is not uncontroversial or unproblematic, and adopting it as a solution raises questions. Perceptual experiences depend on stimuli which arrive at various sensory organs from the external world and these stimuli cause changes in mental states; ultimately causing sensation. A desire

for food, for example, will tend to cause a person to move their body

in a manner and in a direction to obtain food. The question, then, is

how it can be possible for conscious experiences to arise out of an

organ (the human brain) possessing electrochemical properties. A related problem is to explain how propositional attitudes (e.g. beliefs and desires) can cause neurons of the brain to fire and muscles to contract in the correct manner. These comprise some of the puzzles that have confronted epistemologists and philosophers of mind from at least the time of René Descartes.

Continuity of consciousness

Locke's conception

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding in four books (1690) by John Locke (1632–1704)

John Locke considered personal identity (or the self) to be founded on consciousness (viz. memory), and not on the substance of either the soul or the body. Book II Chapter XXVII entitled "On Identity and Diversity" in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) has been said to be one of the first modern conceptualizations of consciousness as the repeated self-identification of oneself. Through this identification, moral responsibility could be attributed to the subject and punishment and guilt could be justified, as critics such as Nietzsche would point out.

According to Locke, personal identity (the self) "depends on

consciousness, not on substance" nor on the soul. We are the same person

to the extent that we are conscious of the past and future thoughts and

actions in the same way as we are conscious of present thoughts and

actions. If consciousness is this "thought" which "goes along with the

substance [...] which makes the same person", then personal identity is

only founded on the repeated act of consciousness: "This may show us

wherein personal identity consists: not in the identity of substance,

but [...] in the identity of consciousness". For example, one may claim

to be a reincarnation

of Plato, therefore having the same soul substance. However, one would

be the same person as Plato only if one had the same consciousness of

Plato's thoughts and actions that he himself did. Therefore,

self-identity is not based on the soul. One soul may have various

personalities.

Neither is self-identity founded on the body substance, argues

Locke, as the body may change while the person remains the same. Even

the identity of animals is not founded on their body: "animal identity

is preserved in identity of life, and not of substance", as the body of

the animal grows and changes during its life. On the other hand,

identity of humans is based on their consciousness.

But this interesting border-case leads to this problematic

thought that since personal identity is based on consciousness, and that

only oneself can be aware of his consciousness, exterior human judges

may never know if they really are judging—and punishing—the same person,

or simply the same body. In other words, Locke argues that may be

judged only for the acts of the body, as this is what is apparent to all

but God; however, are in truth only responsible for the acts for which

are conscious. This forms the basis of the insanity defense: one cannot be held accountable for acts from which one was unconscious—and therefore leads to interesting philosophical questions:

...personal identity consists [not in the identity of substance] but in the identity of consciousness, wherein if Socrates and the present mayor of Queenborough agree, they are the same person: if the same Socrates waking and sleeping do not partake of the same consciousness, Socrates waking and sleeping is not the same person. And to punish Socrates waking for what sleeping Socrates thought, and waking Socrates was never conscious of, would be no more right, than to punish one twin for what his brother-twin did, whereof he knew nothing, because their outsides were so like, that they could not be distinguished; for such twins have been seen.

Or again:

PERSON, as I take it, is the name for this self. Wherever a man finds what he calls himself, there, I think, another may say is the same person. It is a forensic term, appropriating actions and their merit; and so belong only to intelligent agents, capable of a law, and happiness, and misery. This personality extends itself beyond present existence to what is past, only by consciousness,—whereby it becomes concerned and accountable; owns and imputes to itself past actions, just upon the same ground and for the same reason as it does the present. All which is founded in a concern for happiness, the unavoidable concomitant of consciousness; that which is conscious of pleasure and pain, desiring that that self that is conscious should be happy. And therefore whatever past actions it cannot reconcile or APPROPRIATE to that present self by consciousness, it can be no more concerned in it than if they had never been done: and to receive pleasure or pain, i.e. reward or punishment, on the account of any such action, is all one as to be made happy or miserable in its first being, without any demerit at all. For, supposing a MAN punished now for what he had done in another life, whereof he could be made to have no consciousness at all, what difference is there between that punishment and being CREATED miserable? And therefore, conformable to this, the apostle tells us, that, at the great day, when every one shall 'receive according to his doings, the secrets of all hearts shall be laid open.' The sentence shall be justified by the consciousness all person shall have, that THEY THEMSELVES, in what bodies soever they appear, or what substances soever that consciousness adheres to, are the SAME that committed those actions, and deserve that punishment for them.

Henceforth, Locke's conception of personal identity founds it not on

the substance or the body, but in the "same continued consciousness",

which is also distinct from the soul since the soul may have no

consciousness of itself (as in reincarnation).

He creates a third term between the soul and the body—and Locke's

thought may certainly be meditated by those who, following a scientist ideology,

would identify too quickly the brain to consciousness. For the brain,

as the body and as any substance, may change, while consciousness

remains the same. Therefore, personal identity is not in the brain, but in consciousness.

However, Locke's theory of self reveals debt to theology and to apocalyptic "great day", which by advance excuse any failings of human justice and therefore humanity's miserable state. The problem of personal identity is at the center of discussions about life after death and, to a lesser extent, immortality. In order to exist after death, there has to be a person after death who is the same person as the person who died.

Philosophical intuition

Bernard Williams presents a thought experiment appealing to the intuitions about what it is to be the same person in the future. The thought experiment consists of two approaches to the same experiment.

For the first approach Williams suggests that suppose that

there is some process by which subjecting two persons to it can result

in the two persons have "exchanged" bodies. The process has put into the body of person B the memories, behavioral dispositions, and psychological characteristics of the person who prior to undergoing the process belonged to person A; and conversely with person B.

To show this one is to suppose that before undergoing the process

person A and B are asked to which resulting person, A-Body-Person or

B-Body-Person, they wish to receive a punishment and which a reward.

Upon undergoing the process and receiving either the punishment or

reward, it appears to that A-Body-Person expresses the memories of

choosing who gets which treatment as if that person was person B;

conversely with B-Body-Person.

This sort of approach to the thought experiment appears to show

that since the person who expresses the psychological characteristics of

person A to be person A, then intuition is that psychological continuity is the criterion for personal identity.

The second approach is to suppose that someone is told that one will have memories erased and then one will be tortured. Does one need to be afraid

of being tortured? The intuition is that people will be afraid of being

tortured, since it will still be one despite not having one's memories.

Next, Williams asked one to consider several similar scenarios.

Intuition is that in all the scenarios one is to be afraid of being

tortured, that it is still one's self despite having one's memories

erased and receiving new memories. However, the last scenario is an identical scenario to the one in the first scenario.

In the first approach, intuition is to show that one's psychological continuity is the criterion for personal identity, but in second approach, intuition is that it is one's bodily continuity

that is the criterion for personal identity. To resolve this conflict

Williams feels one's intuition in the second approach is stronger and if

he was given the choice of distributing a punishment and a reward he

would want his body-person to receive the reward and the other

body-person to receive the punishment, even if that other body-person

has his memories.

Psychological continuity

In psychology, personal continuity, also called personal persistence or self-continuity, is the uninterrupted connection concerning a particular person of his or her private life and personality. Personal continuity is the union affecting the facets arising from personality in order to avoid discontinuities from one moment of time to another time. Personal continuity is an important part of identity; this is the process of ensuring that the qualities of the mind, such as self-awareness, sentience, sapience, and the ability to perceive

the relationship between oneself and one's environment, are consistent

from one moment to the next. Personal continuity is the property of a

continuous and connected period of time and is intimately related to do with a person's body or physical being in a single four-dimensional continuum. Associationism,

a theory of how ideas combine in the mind, allows events or views to be

associated with each other in the mind, thus leading to a form of

learning. Associations can result from contiguity,

similarity, or contrast. Through contiguity, one associates ideas or

events that usually happen to occur at the same time. Some of these

events form an autobiographical memory in which each is a personal representation of the general or specific events and personal facts.

Ego integrity is the psychological concept of the ego's accumulated assurance of its capacity for order and meaning. Ego identity is the accrued confidence that the inner sameness

and continuity prepared in the past are matched by the sameness and

continuity of one's meaning for others, as evidenced in the promise of a

career. Body and ego control organ expressions. and of the other attributes of the dynamics of a physical system to face the emotions of ego death in circumstances which can summon, sometimes anti-theonymistic, self-abandonment.

Identity continuum

It has been argued that from the nature of sensations and ideas there is no such thing as a permanent identity.

Daniel Shapiro asserts that one of four major views on identity does

not recognize a "permanent identity" and instead thinks of "thoughts

without a thinker" − "a consciousness shell with drifting emotions and

thoughts but no essence". According to him this view is based on the

Buddhist concept of Anatta − "a continuously evolving flow of awareness". Malcolm David Eckel states that "the self changes at every moment and has no permanent identity" − it is a "constant process of changing or becoming", a "fluid ever-changing self".

Bundle theory of the self

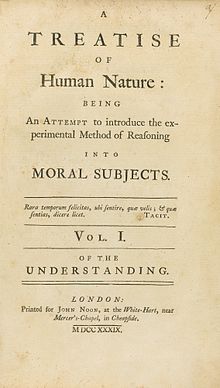

A

Treatise Of Human Nature: Being An Attempt To Introduce The

Experimental Method Of Reasoning Into Moral Subjects. For John Noon,

1739

David Hume undertook looking at the mind–body problem.

Hume also investigated a person's character, the relationship between

human and animal nature, and the nature of agency. Hume pointed out that

we tend to think that we are the same person we were five years ago.

Though we've changed in many respects, the same person appears present

as was present then. We might start thinking about which features can be

changed without changing the underlying self. Hume, however, denies

that there is a distinction between the various features of a person and

the mysterious self that supposedly bears those features. When we start

introspecting, "we are never intimately conscious of anything but a

particular perception; man is a bundle

or collection of different perceptions which succeed one another with

an inconceivable rapidity and are in perpetual flux and movement".

It is plain that in the course of our thinking, and in the

constant revolution of our ideas, our imagination runs easily from one

idea to any other that resembles it, and that this quality alone is to

the fancy a sufficient bond and association. It is likewise evident that

as the senses, in changing their objects, are necessitated to change

them regularly, and take them as they lie contiguous to each other, the

imagination must by long custom acquire the same method of thinking, and

run along the parts of space and time in conceiving its objects.

Note in particular that, in Hume's view, these perceptions do not belong to anything. Hume, similar to the Buddha, compares the soul to a commonwealth,

which retains its identity not by virtue of some enduring core

substance, but by being composed of many different, related, and yet constantly changing elements. The question of personal identity then becomes a matter of characterizing the loose cohesion of one's personal experience.

In short, what matters for Hume is not that 'identity' exists but

that the relations of causation, contiguity, and resemblances obtain

among the perceptions. Critics

of Hume state in order for the various states and processes of the mind

to seem unified, there must be something which perceives their unity,

the existence of which would be no less mysterious than a personal

identity. Hume solves this by considering substance as engendered by the

togetherness of its properties.

No-self theory

The "no-self theory" holds that the self cannot be reduced to a bundle because the concept of a self is incompatible with the idea of a bundle. Propositionally, the idea of a bundle implies the notion of bodily or psychological relations that do not in fact exist. James Giles, a principal exponent of this view, argues that the no-self or eliminativist theory and the bundle or reductionist theory agree about the non-existence of a substantive self. The reductionist theory, according to Giles, mistakenly resurrects the idea of the self in terms of various accounts about psychological relations. The no-self theory, on the other hand, "lets the self lie where it has fallen".

This is because the no-self theory rejects all theories of the self,

even the bundle theory. On Giles' reading, Hume is actually a no-self

theorist and it is a mistake to attribute to him a reductionist view

like the bundle theory. Hume's assertion that personal identity is a fiction supports this reading, according to Giles.

The Buddhist view of personal identity is also a no-self theory rather than a reductionist theory, because the Buddha rejects attempts to reconstructions in terms of consciousness, feelings, or the body in notions of an eternal/permanent, unchanging self since our thoughts, personalities and bodies are never the same from moment to moment.

According to this line of criticism, the sense of self is an evolutionary artifact, which saves time in the circumstances it evolved for. But sense of self breaks down when considering some events such as memory loss, split personality disorder, brain damage, brainwashing, and various thought experiments. When presented with imperfections in the intuitive sense of self and the consequences to this concept which rely on the strict concept of self, a tendency to mend the concept occurs, possibly because of cognitive dissonance.