In physical cosmology, Big Bang nucleosynthesis (abbreviated BBN, also known as primordial nucleosynthesis, arch(a)eonucleosynthesis, archonucleosynthesis, protonucleosynthesis and pal(a)eonucleosynthesis) refers to the production of nuclei other than those of the lightest isotope of hydrogen (hydrogen-1, 1H, having a single proton as a nucleus) during the early phases of the Universe. Primordial nucleosynthesis is believed by most cosmologists to have taken place in the interval from roughly 10 seconds to 20 minutes after the Big Bang, and is calculated to be responsible for the formation of most of the universe's helium as the isotope helium-4 (4He), along with small amounts of the hydrogen isotope deuterium (2H or D), the helium isotope helium-3 (3He), and a very small amount of the lithium isotope lithium-7 (7Li). In addition to these stable nuclei, two unstable or radioactive isotopes were also produced: the heavy hydrogen isotope tritium (3H or T); and the beryllium isotope beryllium-7 (7Be); but these unstable isotopes later decayed into 3He and 7Li, as above.

Essentially all of the elements that are heavier than lithium were created much later, by stellar nucleosynthesis in evolving and exploding stars.

Characteristics

There are several important characteristics of Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN):

- The initial conditions (neutron-proton ratio) were set in the first second after the Big Bang.

- The universe was very close to homogeneous at this time, and strongly radiation-dominated.

- The fusion of nuclei occurred between roughly 10 seconds to 20 minutes after the Big Bang; this corresponds to the temperature range when the universe was cool enough for deuterium to survive, but hot and dense enough for fusion reactions to occur at a significant rate.

- It was widespread, encompassing the entire observable universe.

The key parameter which allows one to calculate the effects of BBN is

the baryon/photon number ratio, which is a small number of order 6 × 10−10.

This parameter corresponds to the baryon density and controls the rate

at which nucleons collide and react; from this it is possible to

calculate element abundances after nucleosynthesis ends. Although the

baryon per photon ratio is important in determining element abundances,

the precise value makes little difference to the overall picture.

Without major changes to the Big Bang theory itself, BBN will result in

mass abundances of about 75% of hydrogen-1, about 25% helium-4, about 0.01% of deuterium and helium-3, trace amounts (on the order of 10−10)

of lithium, and negligible heavier elements. That the observed

abundances in the universe are generally consistent with these abundance

numbers is considered strong evidence for the Big Bang theory.

In this field, for historical reasons it is customary to quote the helium-4 fraction by mass, symbol Y, so that 25% helium-4 means that helium-4 atoms account for 25% of the mass,

but less than 8% of the nuclei would be helium-4 nuclei. Other (trace)

nuclei are usually expressed as number ratios to hydrogen.

Important parameters

The

creation of light elements during BBN was dependent on a number of

parameters; among those was the neutron-proton ratio (calculable from Standard Model physics) and the baryon-photon ratio.

Neutron–proton ratio

The neutron-proton ratio was set by Standard Model physics before the nucleosynthesis era,

essentially within the first 1-second after the Big Bang.

Neutrons can react with positrons or electron neutrinos to create protons and other products in one of the following reactions:

At times much earlier than 1 sec, these reactions were fast and

maintained the n/p ratio close to 1:1. As the temperature dropped, the

equilibrium shifted in favour of protons due to their slightly lower

mass, and the n/p ratio smoothly decreased.

These reactions continued until the decreasing temperature and density

caused the reactions to become too slow, which occurred at about T = 0.7

MeV (time around 1 second) and is called the freeze out temperature. At

freeze out, the neutron-proton ratio was about 1/6. However, free

neutrons are unstable with a mean life of 880 sec; some neutrons decayed

in the next few minutes before fusing into any nucleus, so the ratio of

total neutrons to protons after nucleosynthesis ends is about 1/7.

Almost all neutrons that fused instead of decaying ended up combined

into helium-4, due to the fact that helium-4 has the highest binding energy

per nucleon among light elements. This predicts that about 8% of all

atoms should be helium-4, leading to a mass fraction of helium-4 of

about 25%, which is in line with observations. Small traces of deuterium

and helium-3 remained as there was insufficient time and density for

them to react and form helium-4.

Baryon–photon ratio

The

baryon–photon ratio, η, is the key parameter determining the abundances

of light elements after nucleosynthesis ends. Baryons and light

elements can fuse in the following main reactions:

|

|

along with some other low-probability reactions leading to 7Li or 7Be.

(An important feature is that there are no stable nuclei with mass 5 or 8, which implies that reactions adding one baryon to 4He, or fusing two 4He, do not occur).

Most fusion chains during BBN ultimately terminate in 4He (helium-4), while "incomplete" reaction chains lead to small amounts of left-over 2H or 3He;

the amount of these decreases with increasing baryon-photon ratio. That

is, the larger the baryon-photon ratio the more reactions there will be

and the more efficiently deuterium will be eventually transformed into

helium-4. This result makes deuterium a very useful tool in measuring

the baryon-to-photon ratio.

Sequence

The main nuclear reaction chains for Big Bang nucleosynthesis

Big Bang nucleosynthesis began roughly 10 seconds after the big bang,

when the universe had cooled sufficiently to allow deuterium nuclei to

survive disruption by high-energy photons. (Note that the neutron-proton

freeze-out time was earlier). This time is essentially independent of

dark matter content, since the universe was highly radiation dominated

until much later, and this dominant component controls the

temperature/time relation. At this time there were about

six protons for every neutron, but a small fraction of the neutrons

decay before fusing in the next few hundred seconds, so at the end of

nucleosynthesis there are about seven protons to every neutron, and

almost all the neutrons are in Helium-4 nuclei. The sequence of these

reaction chains is shown on the image.

One feature of BBN is that the physical laws and constants that

govern the behavior of matter at these energies are very well

understood, and hence BBN lacks some of the speculative uncertainties

that characterize earlier periods in the life of the universe. Another

feature is that the process of nucleosynthesis is determined by

conditions at the start of this phase of the life of the universe, and

proceeds independently of what happened before.

As the universe expands, it cools. Free neutrons

are less stable than helium nuclei, and the protons and neutrons have a

strong tendency to form helium-4. However, forming helium-4 requires

the intermediate step of forming deuterium. Before nucleosynthesis

began, the temperature was high enough for many photons to have energy

greater than the binding energy of deuterium; therefore any deuterium

that was formed was immediately destroyed (a situation known as the deuterium bottleneck).

Hence, the formation of helium-4 is delayed until the universe became

cool enough for deuterium to survive (at about T = 0.1 MeV); after which

there was a sudden burst of element formation. However, very shortly

thereafter, around twenty minutes after the Big Bang, the temperature

and density became too low for any significant fusion to occur. At this

point, the elemental abundances were nearly fixed, and the only changes

were the result of the radioactive decay of the two major unstable products of BBN, tritium and beryllium-7.

History of theory

The history of Big Bang nucleosynthesis began with the calculations of Ralph Alpher in the 1940s. Alpher published the Alpher–Bethe–Gamow paper that outlined the theory of light-element production in the early universe.

During the 1970s, there was a major puzzle in that the density of

baryons as calculated by Big Bang nucleosynthesis was much less than

the observed mass of the universe based on measurements of galaxy

rotation curves and galaxy cluster dynamics. This puzzle was resolved in

large part by postulating the existence of dark matter.

Heavy elements

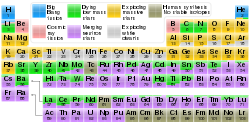

A version of the periodic table indicating the origins – including big bang nucleosynthesis – of the elements. All elements above 103 (lawrencium) are also manmade and are not included.

Big Bang nucleosynthesis produced very few nuclei of elements heavier than lithium due to a bottleneck: the absence of a stable nucleus with 8 or 5 nucleons. This deficit of larger atoms also limited the amounts of lithium-7 produced during BBN. In stars, the bottleneck is passed by triple collisions of helium-4 nuclei, producing carbon (the triple-alpha process).

However, this process is very slow and requires much higher densities,

taking tens of thousands of years to convert a significant amount of

helium to carbon in stars, and therefore it made a negligible

contribution in the minutes following the Big Bang.

The predicted abundance of CNO isotopes produced in Big Bang nucleosynthesis is expected to be on the order of 10−15 that of H, making them essentially undetectable and negligible.

Indeed, none of these primordial isotopes of the elements from lithium

to oxygen have yet been detected, although those of beryllium and boron

may be able to be detected in the future. So far, the only stable

nuclides known experimentally to have been made before or during Big

Bang nucleosynthesis are protium, deuterium, helium-3, helium-4, and

lithium-7.

Helium-4

Big Bang nucleosynthesis predicts a primordial abundance of about 25%

helium-4 by mass, irrespective of the initial conditions of the

universe. As long as the universe was hot enough for protons and

neutrons to transform into each other easily, their ratio, determined

solely by their relative masses, was about 1 neutron to 7 protons

(allowing for some decay of neutrons into protons). Once it was cool

enough, the neutrons quickly bound with an equal number of protons to

form first deuterium, then helium-4. Helium-4 is very stable and is

nearly the end of this chain if it runs for only a short time, since

helium neither decays nor combines easily to form heavier nuclei (since

there are no stable nuclei with mass numbers of 5 or 8, helium does not

combine easily with either protons, or with itself). Once temperatures

are lowered, out of every 16 nucleons (2 neutrons and 14 protons), 4 of

these (25% of the total particles and total mass) combine quickly into

one helium-4 nucleus. This produces one helium for every 12 hydrogens,

resulting in a universe that is a little over 8% helium by number of

atoms, and 25% helium by mass.

One analogy is to think of helium-4 as ash, and the amount of ash

that one forms when one completely burns a piece of wood is insensitive

to how one burns it. The resort to the BBN theory of the helium-4

abundance is necessary as there is far more helium-4 in the universe

than can be explained by stellar nucleosynthesis.

In addition, it provides an important test for the Big Bang theory. If

the observed helium abundance is significantly different from 25%, then

this would pose a serious challenge to the theory. This would

particularly be the case if the early helium-4 abundance was much

smaller than 25% because it is hard to destroy helium-4. For a few years

during the mid-1990s, observations suggested that this might be the

case, causing astrophysicists to talk about a Big Bang nucleosynthetic

crisis, but further observations were consistent with the Big Bang

theory.

Deuterium

Deuterium is in some ways the opposite of helium-4, in that while

helium-4 is very stable and difficult to destroy, deuterium is only

marginally stable and easy to destroy. The temperatures, time, and

densities were sufficient to combine a substantial fraction of the

deuterium nuclei to form helium-4 but insufficient to carry the process

further using helium-4 in the next fusion step. BBN did not convert all

of the deuterium in the universe to helium-4 due to the expansion that

cooled the universe and reduced the density, and so cut that conversion

short before it could proceed any further. One consequence of this is

that, unlike helium-4, the amount of deuterium is very sensitive to

initial conditions. The denser the initial universe was, the more

deuterium would be converted to helium-4 before time ran out, and the

less deuterium would remain.

There are no known post-Big Bang processes which can produce

significant amounts of deuterium. Hence observations about deuterium

abundance suggest that the universe is not infinitely old, which is in

accordance with the Big Bang theory.

During the 1970s, there were major efforts to find processes that

could produce deuterium, but those revealed ways of producing isotopes

other than deuterium. The problem was that while the concentration of

deuterium in the universe is consistent with the Big Bang model as a

whole, it is too high to be consistent with a model that presumes that

most of the universe is composed of protons and neutrons.

If one assumes that all of the universe consists of protons and

neutrons, the density of the universe is such that much of the currently

observed deuterium would have been burned into helium-4.

The standard explanation now used for the abundance of deuterium is

that the universe does not consist mostly of baryons, but that

non-baryonic matter (also known as dark matter) makes up most of the mass of the universe.

This explanation is also consistent with calculations that show that a

universe made mostly of protons and neutrons would be far more clumpy than is observed.

It is very hard to come up with another process that would

produce deuterium other than by nuclear fusion. Such a process would

require that the temperature be hot enough to produce deuterium, but not

hot enough to produce helium-4, and that this process should

immediately cool to non-nuclear temperatures after no more than a few

minutes. It would also be necessary for the deuterium to be swept away

before it reoccurs.

Producing deuterium by fission is also difficult. The problem

here again is that deuterium is very unlikely due to nuclear processes,

and that collisions between atomic nuclei are likely to result either in

the fusion of the nuclei, or in the release of free neutrons or alpha particles. During the 1970s, cosmic ray spallation

was proposed as a source of deuterium. That theory failed to account

for the abundance of deuterium, but led to explanations of the source of

other light elements.

Lithium

Lithium-7 and lithium-6 produced in the Big Bang are in the order of: lithium-7 to be 10−9 of all primordial nuclides; and lithium-6 around 10−13.

Measurements and status of theory

The

theory of BBN gives a detailed mathematical description of the

production of the light "elements" deuterium, helium-3, helium-4, and

lithium-7. Specifically, the theory yields precise quantitative

predictions for the mixture of these elements, that is, the primordial

abundances at the end of the big-bang.

In order to test these predictions, it is necessary to

reconstruct the primordial abundances as faithfully as possible, for

instance by observing astronomical objects in which very little stellar nucleosynthesis has taken place (such as certain dwarf galaxies)

or by observing objects that are very far away, and thus can be seen in

a very early stage of their evolution (such as distant quasars).

As noted above, in the standard picture of BBN, all of the light element abundances depend on the amount of ordinary matter (baryons) relative to radiation (photons). Since the universe is presumed to be homogeneous,

it has one unique value of the baryon-to-photon ratio. For a long time,

this meant that to test BBN theory against observations one had to ask:

can all of the light element observations be explained with a single value

of the baryon-to-photon ratio? Or more precisely, allowing for the

finite precision of both the predictions and the observations, one asks:

is there some range of baryon-to-photon values which can account for all of the observations?

More recently, the question has changed: Precision observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation with the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and Planck

give an independent value for the baryon-to-photon ratio. Using this

value, are the BBN predictions for the abundances of light elements in

agreement with the observations?

The present measurement of helium-4 indicates good agreement, and

yet better agreement for helium-3. But for lithium-7, there is a

significant discrepancy between BBN and WMAP/Planck, and the abundance

derived from Population II stars.

The discrepancy is a factor of 2.4―4.3 below the theoretically

predicted value and is considered a problem for the original models,[14]

that have resulted in revised calculations of the standard BBN based on

new nuclear data, and to various reevaluation proposals for primordial proton-proton nuclear reactions, especially the abundances of 7Be + n → 7Li + p, versus 7Be + 2H → 8Be + p.

Non-standard scenarios

In addition to the standard BBN scenario there are numerous non-standard BBN scenarios. These should not be confused with non-standard cosmology:

a non-standard BBN scenario assumes that the Big Bang occurred, but

inserts additional physics in order to see how this affects elemental

abundances. These pieces of additional physics include relaxing or

removing the assumption of homogeneity, or inserting new particles such

as massive neutrinos.

There have been, and continue to be, various reasons for

researching non-standard BBN. The first, which is largely of historical

interest, is to resolve inconsistencies between BBN predictions and

observations. This has proved to be of limited usefulness in that the

inconsistencies were resolved by better observations, and in most cases

trying to change BBN resulted in abundances that were more inconsistent

with observations rather than less. The second reason for researching

non-standard BBN, and largely the focus of non-standard BBN in the early

21st century, is to use BBN to place limits on unknown or speculative

physics. For example, standard BBN assumes that no exotic hypothetical

particles were involved in BBN. One can insert a hypothetical particle

(such as a massive neutrino) and see what has to happen before BBN

predicts abundances that are very different from observations. This has

been done to put limits on the mass of a stable tau neutrino.