Opium poppies such as this one provide ingredients for the class of analgesics called opiates

Pain management, pain medicine, pain control or algiatry, is a branch of medicine employing an interdisciplinary approach for easing the suffering and improving the quality of life of those living with chronic pain The typical pain management team includes medical practitioners, pharmacists, clinical psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, physician assistants, nurses. The team may also include other mental health specialists and massage therapists. Pain sometimes resolves promptly once the underlying trauma or pathology has healed, and is treated by one practitioner, with drugs such as analgesics and (occasionally) anxiolytics. Effective management of chronic (long-term) pain, however, frequently requires the coordinated efforts of the management team.

Medicine treats injury and pathology to support and speed healing; and treats distressing symptoms such as pain to relieve suffering

during treatment and healing. When a painful injury or pathology is

resistant to treatment and persists, when pain persists after the injury

or pathology has healed, and when medical science cannot identify the

cause of pain, the task of medicine is to relieve suffering. Treatment

approaches to chronic pain include pharmacological measures, such as analgesics, antidepressants and anticonvulsants, interventional procedures, physical therapy, physical exercise, application of ice and/or heat, and psychological measures, such as biofeedback and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Uses

Pain

can have many causes and there are many possible treatments for it. In

the nursing profession, one common definition of pain is any problem

that is "whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever

the experiencing person says it does". Different sorts of pain management address different sorts of pain.

Pain management includes patient communication about the pain problem. To define the pain problem, a health care provider will likely ask questions such as these:

- How intense is the pain?

- How does the pain feel?

- Where is the pain?

- What, if anything, makes the pain lessen?

- What, if anything, makes the pain increase?

- When did the pain start?

After asking questions such as these, the health care provider will have a description of the pain. Pain management will then be used to address that pain.

Adverse effects

There are many types of pain management, and each of them have their own benefits, drawbacks, and limits.

A common difficulty in pain management is communication. People experiencing pain may have difficulty recognizing or describing what they feel and how intense it is. Health care providers and patients may have difficulty communicating with each other about how pain responds to treatments.

There is a continuing risk in many types of pain management for the

patient to take treatment which is less effective than needed or which

causes other difficulty and side effects. Some treatments for pain can be harmful if overused.

A goal of pain management for the patient and their health care

provider to identify the amount of treatment which addresses the pain

but which is not too much treatment.

Another problem with pain management is that pain is the body's natural way of communicating a problem. Pain is supposed to resolve as the body heals itself with time and pain management. Sometimes pain management covers a problem, and the patient might be less aware that they need treatment for a deeper problem.

Physical approach

Physical medicine and rehabilitation

Physical medicine and rehabilitation employs diverse physical techniques such as thermal agents and electrotherapy,

as well as therapeutic exercise and behavioral therapy, alone or in

tandem with interventional techniques and conventional pharmacotherapy

to treat pain, usually as part of an interdisciplinary or

multidisciplinary program.

The Center for Disease Control recommends that physical therapy and

exercise can be prescribed as a positive alternative to opioids for

decreasing one's pain in multiple injuries, illnesses, or diseases. This can include chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis of the hip and knee, or fibromyalgia.

Exercise alone or with other rehabilitation disciplines (such as

psychologically based approaches) can have a positive effect on reducing

pain. In addition to improving pain, exercise also can improve one's well-being and general health.

Exercise interventions

Physical

activity interventions, such as tai chi, yoga and Pilates, promote

harmony of the mind and body through total body awareness. These ancient

practices incorporate breathing techniques, meditation and a wide

variety of movements, while training the body to perform functionally by

increasing strength, flexibility, and range of motion. Physical activity and exercise may improve chronic pain (pain lasting more than 12 weeks), and overall quality of life, while minimizing the need for pain medications.

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has been found to be ineffective for lower back pain, however, it might help with diabetic neuropathy.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture

involves the insertion and manipulation of needles into specific points

on the body to relieve pain or for therapeutic purposes. An analysis of

the 13 highest quality studies of pain treatment with acupuncture,

published in January 2009 in the British Medical Journal, was unable to quantify the difference in the effect on pain of real, sham and no acupuncture.

Light therapy

Research has not found evidence that light therapy such as low level laser therapy is an effective therapy for relieving low back pain.

Interventional procedures

Interventional procedures - typically used for chronic back pain - include epidural steroid injections, facet joint injections, neurolytic blocks, spinal cord stimulators and intrathecal drug delivery system implants.

Pulsed radiofrequency, neuromodulation, direct introduction of medication and nerve ablation may be used to target either the tissue structures and organ/systems responsible for persistent nociception or the nociceptors from the structures implicated as the source of chronic pain.

An intrathecal pump

used to deliver very small quantities of medications directly to the

spinal fluid. This is similar to epidural infusions used in labour

and postoperatively. The major differences are that it is much more

common for the drug to be delivered into the spinal fluid (intrathecal)

rather than epidurally, and the pump can be fully implanted under the

skin.

A spinal cord stimulator

is an implantable medical device that creates electric impulses and

applies them near the dorsal surface of the spinal cord provides a paresthesia ("tingling") sensation that alters the perception of pain by the patient.

Psychological approach

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT) for pain helps patients with pain to understand the relationship

between one's physiology (e.g., pain and muscle tension), thoughts,

emotions, and behaviors. A main goal in treatment is cognitive

restructuring to encourage helpful thought patterns, targeting a

behavioral activation of healthy activities such as regular exercise and

pacing. Lifestyle changes are also trained to improve sleep patterns

and to develop better coping skills for pain and other stressors using

various techniques (e.g., relaxation, diaphragmatic breathing, and even

biofeedback).

Studies have demonstrated the usefulness of cognitive behavioral

therapy in the management of chronic low back pain, producing

significant decreases in physical and psychosocial disability.

CBT is significantly more effective than standard care in treatment of

people with body-wide pain, like fibromyalgia. Evidence for the

usefulness of CBT in the management of adult chronic pain is generally

poorly understood, due partly to the proliferation of techniques of

doubtful quality, and the poor quality of reporting in clinical trials.

The crucial content of individual interventions has not been isolated

and the important contextual elements, such as therapist training and

development of treatment manuals, have not been determined. The widely

varying nature of the resulting data makes useful systematic review and meta-analysis within the field very difficult.

In 2012, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

(RCTs) evaluated the clinical effectiveness of psychological therapies

for the management of adult chronic pain (excluding headaches). There is

no evidence that behaviour therapy

(BT) is effective for reducing this type of pain, however BT may be

useful for improving a persons mood immediately after treatment. This

improvement appears to be small, and is short term in duration.

CBT may have a small positive short-term effect on pain immediately

following treatment. CBT may also have a small effect on reducing disability and potential catastrophizing that may be associated with adult chronic pain. These benefits do not appear to last very long following the therapy.

CBT may contribute towards improving the mood of an adult who

experiences chronic pain, and there is a possibility that this benefit

may be maintained for longer periods of time.

For children and adolescents, a review of RCTs evaluating the

effectiveness of psychological therapy for the management of chronic and

recurrent pain found that psychological treatments are effective in

reducing pain when people under 18 years old have headaches. This

beneficial effect may be maintained for at least three months following

the therapy.

Psychological treatments may also improve pain control for children or

adolescents who experience pain not related to headaches. It is not

known if psychological therapy improves a child or adolescents mood and

the potential for disability related to their chronic pain.

Hypnosis

A 2007 review of 13 studies found evidence for the efficacy of hypnosis

in the reduction of pain in some conditions, though the number of

patients enrolled in the studies was small, bringing up issues of power

to detect group differences, and most lacked credible controls for

placebo and/or expectation. The authors concluded that "although the

findings provide support for the general applicability of hypnosis in

the treatment of chronic pain, considerably more research will be needed

to fully determine the effects of hypnosis for different chronic-pain

conditions."

Hypnosis has reduced the pain of some noxious medical procedures in children and adolescents,

and in clinical trials addressing other patient groups it has

significantly reduced pain compared to no treatment or some other

non-hypnotic interventions.

However, no studies have compared hypnosis to a convincing placebo, so

the pain reduction may be due to patient expectation (the "placebo

effect"). The effects of self hypnosis on chronic pain are roughly comparable to those of progressive muscle relaxation.

Mindfulness meditation

A meta-analysis of studies that used techniques centered around the concept of mindfulness, concluded, "Findings suggest that MBIs decrease the intensity of pain for chronic pain patients."

Medications

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a pain ladder for managing analgesia. It was first described for use in cancer pain, but it can be used by medical professionals as a general principle when dealing with analgesia for any type of pain.

In the treatment of chronic pain, whether due to malignant or benign

processes, the three-step WHO Analgesic Ladder provides guidelines for

selecting the kind and stepping up the amount of analgesia. The exact

medications recommended will vary with the country and the individual

treatment center, but the following gives an example of the WHO approach

to treating chronic pain with medications. If, at any point, treatment

fails to provide adequate pain relief, then the doctor and patient move

onto the next step.

| Common types of pain and typical drug management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain type | typical initial drug treatment | comments | |

| headache | paracetamol /acetaminophen, NSAIDs | doctor consultation is appropriate if headaches are severe, persistent, accompanied by fever, vomiting, or speech or balance problems; self-medication should be limited to two weeks | |

| migraine | paracetamol, NSAIDs | triptans are used when the others do not work, or when migraines are frequent or severe | |

| menstrual cramps | NSAIDs | some NSAIDs are marketed for cramps, but any NSAID would work | |

| minor trauma, such as a bruise, abrasions, sprain | paracetamol, NSAIDs | opioids not recommended | |

| severe trauma, such as a wound, burn, bone fracture, or severe sprain | opioids | more than two weeks of pain requiring opioid treatment is unusual | |

| strain or pulled muscle | NSAIDs, muscle relaxants | if inflammation is involved, NSAIDs may work better; short-term use only | |

| minor pain after surgery | paracetamol, NSAIDs | opioids rarely needed | |

| severe pain after surgery | opioids | combinations of opioids may be prescribed if pain is severe | |

| muscle ache | paracetamol, NSAIDs | if inflammation involved, NSAIDs may work better. | |

| toothache or pain from dental procedures | paracetamol, NSAIDs | this should be short term use; opioids may be necessary for severe pain | |

| kidney stone pain | paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids | opioids usually needed if pain is severe. | |

| pain due to heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease | antacid, H2 antagonist, proton-pump inhibitor | heartburn lasting more than a week requires medical attention; aspirin and NSAIDs should be avoided | |

| chronic back pain | paracetamol, NSAIDs | opioids may be necessary if other drugs do not control pain and pain is persistent | |

| osteoarthritis pain | paracetamol, NSAIDs | medical attention is recommended if pain persists. | |

| fibromyalgia | antidepressant, anticonvulsant | evidence suggests that opioids are not effective in treating fibromyalgia | |

Mild pain

Mild to moderate pain

Paracetamol, an NSAID and/or paracetamol in a combination product with a weak opioid such as tramadol,

may provide greater relief than their separate use. Also a combination

of opioid with acetaminophen can be frequently used such as Percocet,

Vicodin, or Norco.

Moderate to severe pain

When

treating moderate to severe pain, the type of the pain, acute or

chronic, needs to be considered. The type of pain can result in

different medications being prescribed. Certain medications may work

better for acute pain, others for chronic pain, and some may work

equally well on both. Acute pain medication is for rapid onset of pain

such as from an inflicted trauma or to treat post-operative pain. Chronic pain medication is for alleviating long-lasting, ongoing pain.

Morphine is the gold standard to which all narcotics are compared. Semi-synthetic derivatives of morphine such as hydromorphone (Dilaudid), oxymorphone (Numorphan, Opana), nicomorphine (Vilan), hydromorphinol and others vary in such ways as duration of action, side effect profile and milligramme potency. Fentanyl has the benefit of less histamine release and thus fewer side effects. It can also be administered via transdermal patch

which is convenient for chronic pain management. In addition to the

intrathecal patch and injectable Sublimaze, the FDA has approved various

immediate release fentanyl products for breakthrough cancer pain

(Actiq/OTFC/Fentora/Onsolis/Subsys/Lazanda/Abstral). Oxycodone is used across the Americas and Europe for relief of serious chronic pain; its main slow-release formula is known as OxyContin, and short-acting tablets, capsules, syrups and ampules are available making it suitable for acute intractable pain or breakthrough pain. Diamorphine, methadone and buprenorphine are used less frequently. Pethidine, known in North America as meperidine, is not recommended for pain management due to its low potency, short duration of action, and toxicity associated with repeated use. Pentazocine, dextromoramide and dipipanone

are also not recommended in new patients except for acute pain where

other analgesics are not tolerated or are inappropriate, for

pharmacological and misuse-related reasons. In some countries potent

synthetics such as piritramide and ketobemidone are used for severe pain, and tapentadol is a newer agent introduced in the last decade.

For moderate pain, tramadol, codeine, dihydrocodeine, and hydrocodone are used, with nicocodeine, ethylmorphine and propoxyphene and dextropropoxyphene less commonly.

Drugs of other types can be used to help opioids combat certain types of pain, for example, amitriptyline

is prescribed for chronic muscular pain in the arms, legs, neck and

lower back with an opiate, or sometimes without it and/or with an NSAID.

While opiates are often used in the management of chronic pain, high doses are associated with an increased risk of opioid overdose.

Opioids

From the Food and Drug Administration's website: "According to the National Institutes of Health,

studies have shown that properly managed medical use of opioid

analgesic compounds (taken exactly as prescribed) is safe, can manage

pain effectively, and rarely causes addiction."

Opioid

medications can provide short, intermediate or long acting analgesia

depending upon the specific properties of the medication and whether it

is formulated as an extended release drug. Opioid medications may be

administered orally, by injection, via nasal mucosa or oral mucosa,

rectally, transdermally, intravenously, epidurally and intrathecally. In

chronic pain conditions that are opioid responsive a combination of a

long-acting (OxyContin, MS Contin, Opana ER, Exalgo and Methadone) or extended release

medication is often prescribed in conjunction with a shorter-acting

medication (oxycodone, morphine or hydromorphone) for breakthrough pain,

or exacerbations.

Most opioid treatment used by patients outside of healthcare settings is oral (tablet, capsule or liquid), but suppositories and skin patches can be prescribed. An opioid injection is rarely needed for patients with chronic pain.

Although opioids are strong analgesics, they do not provide

complete analgesia regardless of whether the pain is acute or chronic in

origin. Opioids are efficacious analgesics in chronic malignant pain

and modestly effective in nonmalignant pain management. However, there are associated adverse effects, especially during the commencement or change in dose. When opioids are used for prolonged periods drug tolerance, chemical dependency, diversion and addiction may occur.

Clinical guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain have been issued by the American Pain Society

and the American Academy of Pain Medicine. Included in these guidelines

is the importance of assessing the patient for the risk of substance

abuse, misuse, or addiction; a personal or family history of substance

abuse is the strongest predictor of aberrant drug-taking behavior.

Physicians who prescribe opioids should integrate this treatment with

any psychotherapeutic intervention the patient may be receiving. The

guidelines also recommend monitoring not only the pain but also the

level of functioning and the achievement of therapeutic goals. The

prescribing physician should be suspicious of abuse when a patient

reports a reduction in pain but has no accompanying improvement in

function or progress in achieving identified goals.

Commonly-used long-acting opioids and their parent compound:

- OxyContin (oxycodone)

- Hydromorph Contin (hydromorphone)

- MS Contin (morphine)

- M-Eslon (morphine)

- Exalgo (hydromorphone)

- Opana ER (oxymorphone)

- Duragesic (fentanyl)

- Nucynta ER (tapentadol)

- Metadol/Methadose (methadone)*

- Hysingla ER (hydrocodone bitartrate)

- Zohydro ER (hydrocodone bicarbonate)

*Methadone can be used for either treatment of opioid addiction/detoxification

when taken once daily or as a pain medication usually administered on

an every 12-hour or 8-hour dosing interval.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

The other major group of analgesics are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Acetaminophen/paracetamol

is not always included in this class of medications. However,

acetaminophen may be administered as a single medication or in

combination with other analgesics (both NSAIDs and opioids). The

alternatively prescribed NSAIDs such as ketoprofen and piroxicam have limited benefit in chronic pain disorders and with long-term use are associated with significant adverse effects. The use of selective NSAIDs designated as selective COX-2 inhibitors have significant cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risks which have limited their utilization.

Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs

Some antidepressant and antiepileptic

drugs are used in chronic pain management and act primarily within the

pain pathways of the central nervous system, though peripheral

mechanisms have been attributed as well. These mechanisms vary and in

general are more effective in neuropathic pain disorders as well as complex regional pain syndrome.

Cannabinoids

Chronic pain is one of the most commonly cited reasons for the use of medical marijuana.

A 2012 Canadian survey of participants in their medical marijuana

program found that 84% of respondents reported using medical marijuana

for the management of pain.

Evidence of medical marijuana's pain mitigating effects is generally conclusive. Detailed in a 1999 report by the Institute of Medicine, "the available evidence from animal and human studies indicates that cannabinoids can have a substantial analgesic effect". In a 2013 review study published in Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology,

various studies were cited in demonstrating that cannabinoids exhibit

comparable effectiveness to opioids in models of acute pain and even

greater effectiveness in models of chronic pain.

Other analgesics

Other

drugs are often used to help analgesics combat various types of pain,

and parts of the overall pain experience, and are hence called analgesic adjuvant medications. Gabapentin—an anti-epileptic—not only exerts effects alone on neuropathic pain, but can potentiate opiates. While perhaps not prescribed as such, other drugs such as Tagamet (cimetidine) and even simple grapefruit juice may also potentiate opiates, by inhibiting CYP450 enzymes in the liver, thereby slowing metabolism of the drug. In addition, orphenadrine, cyclobenzaprine, trazodone and other drugs with anticholinergic properties are useful in conjunction with opioids for neuropathic pain. Orphenadrine and cyclobenzaprine are also muscle relaxants, and therefore particularly useful in painful musculoskeletal conditions. Clonidine has found use as an analgesic for this same purpose, and all of the mentioned drugs potentiate the effects of opioids overall.

Society and culture

The medical treatment of pain as practiced in Greece and Turkey is called algology (from the Greek άλγος, algos, "pain"). The Hellenic Society of Algology and the Turkish Algology-Pain Society are the relevant local bodies affiliated to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).

Undertreatment

Undertreatment of pain is the absence of pain management therapy for a person in pain when treatment is indicated.

Consensus in evidence-based medicine and the recommendations of medical specialty organizations establish the guidelines which determine the treatment for pain which health care providers ought to offer. For various social reasons, persons in pain may not seek or may not be able to access treatment for their pain.

The Joint Commission, which has long recognized nonpharmacological

approaches to pain, emphasizes the importance of strategies needed to

facilitate both access and coverage to nonpharmacological therapies.

Users of nonpharmacological therapy providers for pain management

generally have lower insurance expenditures than those who did not use

them. At the same time, health care providers may not provide the treatment which authorities recommend.

The need for an informed strategy including all evidence-based

comprehensive pain care is demonstrated to be in the patients' best

interest. Healthcare providers' failure to educate patients and

recommend nonpharmacologic care should be considered unethical.

In children

Acute pain is common in children and adolescents as a result of injury, illness, or necessary medical procedures. Chronic pain is present in approximately 15–25% of children and adolescents, and may be caused by an underlying disease, such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or cancer or by functional disorders such as migraines, fibromyalgia, or complex regional pain.

- Assessment

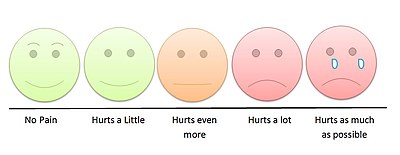

Young children can indicate their level of pain by pointing to the appropriate face on a children's pain scale.

Pain assessment in children is often challenging due to limitations

in developmental level, cognitive ability, or their previous pain

experiences. Clinicians must observe physiological and behavioral cues

exhibited by the child to make an assessment. Self-report, if possible,

is the most accurate measure of pain; self-report pain scales developed

for young children involve matching their pain intensity to photographs

of other children's faces, such as the Oucher Scale, pointing to

schematics of faces showing different pain levels, or pointing out the

location of pain on a body outline.

Questionnaires for older children and adolescents include the

Varni-Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ) and the Children’s

Comprehensive Pain Questionnaire, which are often utilized for

individuals with chronic or persistent pain.

- Nonpharmacologic

Caregivers may provide nonpharmacological treatment for children and

adolescents because it carries minimal risk and is cost effective

compared to pharmacological treatment. Nonpharmacologic interventions

vary by age and developmental factors. Physical interventions to ease

pain in infants include swaddling, rocking, or sucrose via a pacifier,

whereas those for children and adolescents include hot or cold

application, massage, or acupuncture. Cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT) aims to reduce the emotional distress and improve the daily

functioning of school-aged children and adolescents with pain through

focus on changing the relationship between their thoughts and emotions

in addition to teaching them adaptive coping strategies. Integrated interventions in CBT include relaxation technique, mindfulness, biofeedback, and acceptance (in the case of chronic pain). Many therapists will hold sessions for caregivers to provide them with effective management strategies.

- Pharmacologic

Acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and opioid analgesics

are commonly used to treat acute or chronic pain symptoms in children

and adolescents, but a pediatrician should be consulted before

administering any medication.

Professional certification

Pain

management practitioners come from all fields of medicine. In addition

to medical practitioners, a pain management team may often benefit from

the input of pharmacists, physiotherapists, clinical psychologists and occupational therapists, among others. Together the multidisciplinary team can help create a package of care suitable to the patient.

Pain physicians are often fellowship-trained board-certified anesthesiologists, neurologists, physiatrists or psychiatrists. Palliative care doctors are also specialists in pain management. The American Board of Anesthesiology, the American Osteopathic Board of Anesthesiology (recognized by the AOABOS), the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology each provide certification for a subspecialty in pain management following fellowship training which is recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) or the American Osteopathic Association Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists

(AOABOS). As the field of pain medicine has grown rapidly, many

practitioners have entered the field, some non-ACGME board-certified.