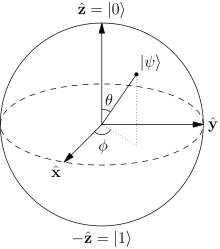

Each point in the Bloch ball is a possible quantum state for a qubit. In QBism, all quantum states are representations of personal probabilities.

In physics and the philosophy of physics, quantum Bayesianism (abbreviated QBism, pronounced "cubism") is an interpretation of quantum mechanics

that takes an agent's actions and experiences as the central concerns

of the theory. This interpretation is distinguished by its use of a subjective Bayesian account of probabilities to understand the quantum mechanical Born rule as a normative addition to good decision-making. Rooted in the prior work of Carlton Caves,

Christopher Fuchs, and Rüdiger Schack during the early 2000s, QBism

itself is primarily associated with Fuchs and Schack and has more

recently been adopted by David Mermin. QBism draws from the fields of quantum information and Bayesian probability

and aims to eliminate the interpretational conundrums that have beset

quantum theory. The QBist interpretation is historically derivative of

the views of the various physicists that are often grouped together as

"the" Copenhagen interpretation, but is itself distinct from them. Theodor Hänsch has characterized QBism as sharpening those older views and making them more consistent.

More generally, any work that uses a Bayesian or personalist (aka

"subjective") treatment of the probabilities that appear in quantum

theory is also sometimes called quantum Bayesian. QBism, in particular, has been referred to as "the radical Bayesian interpretation".

QBism deals with common questions in the interpretation of quantum theory about the nature of wavefunction superposition, quantum measurement, and entanglement.

According to QBism, many, but not all, aspects of the quantum formalism

are subjective in nature. For example, in this interpretation, a

quantum state is not an element of reality—instead it represents the degrees of belief an agent has about the possible outcomes of measurements. For this reason, some philosophers of science have deemed QBism a form of anti-realism.

The originators of the interpretation disagree with this

characterization, proposing instead that the theory more properly aligns

with a kind of realism they call "participatory realism", wherein

reality consists of more than can be captured by any putative third-person account of it.

In addition to presenting an interpretation of the existing mathematical

structure of quantum theory, some QBists have advocated a research

program of reconstructing quantum theory from basic physical

principles whose QBist character is manifest. The ultimate goal of this

research is to identify what aspects of the ontology of the physical world make quantum theory a good tool for agents to use. However, the QBist interpretation itself, as described in the Core positions section, does not depend on any particular reconstruction.

History and development

British philosopher, mathematician, and economist Frank Ramsey, whose interpretation of probability theory closely matches the one adopted by QBism.

E. T. Jaynes,

a promoter of the use of Bayesian probability in statistical physics,

once suggested that quantum theory is "[a] peculiar mixture describing

in part realities of Nature, in part incomplete human information about

Nature—all scrambled up by Heisenberg and Bohr into an omelette that nobody has seen how to unscramble." QBism developed out of efforts to separate these parts using the tools of quantum information theory and personalist Bayesian probability theory.

There are many interpretations of probability theory.

Broadly speaking, these interpretations fall into one of two

categories: those which assert that a probability is an objective

property of reality and those which assert that a probability is a

subjective, mental construct which an agent may use to quantify their

ignorance or degree of belief in a proposition. QBism begins by

asserting that all probabilities, even those appearing in quantum

theory, are most properly viewed as members of the latter category.

Specifically, QBism adopts a personalist Bayesian interpretation along

the lines of Italian mathematician Bruno de Finetti and English philosopher Frank Ramsey.

According to QBists, the advantages of adopting this view of

probability are twofold. First, for QBists the role of quantum states,

such as the wavefunctions of particles, is to efficiently encode

probabilities; so quantum states are ultimately degrees of belief

themselves. (If one considers any single measurement that is a minimal,

informationally complete POVM,

this is especially clear: A quantum state is mathematically equivalent

to a single probability distribution, the distribution over the possible

outcomes of that measurement.)

Regarding quantum states as degrees of belief implies that the event of

a quantum state changing when a measurement occurs—the "collapse of the wave function"—is simply the agent updating her beliefs in response to a new experience. Second, it suggests that quantum mechanics can be thought of as a local theory, because the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR)

criterion of reality can be rejected. The EPR criterion states, "If,

without in any way disturbing a system, we can predict with certainty

(i.e., with probability equal to unity) the value of a physical quantity, then there exists an element of reality corresponding to that quantity." Arguments that quantum mechanics should be considered a nonlocal theory

depend upon this principle, but to a QBist, it is invalid, because a

personalist Bayesian considers all probabilities, even those equal to

unity, to be degrees of belief. Therefore, while many interpretations of quantum theory conclude that quantum mechanics is a nonlocal theory, QBists do not.

Fuchs introduced the term "QBism" and outlined the interpretation in more or less its present form in 2010, carrying further and demanding consistency of ideas broached earlier, notably in publications from 2002. Several subsequent papers have expanded and elaborated upon these foundations, notably a Reviews of Modern Physics article by Fuchs and Schack; an American Journal of Physics article by Fuchs, Mermin, and Schack; and Enrico Fermi Summer School lecture notes by Fuchs and Stacey.

Prior to the 2010 paper, the term "quantum Bayesianism" was used

to describe the developments which have since led to QBism in its

present form. However, as noted above, QBism subscribes to a particular

kind of Bayesianism which does not suit everyone who might apply

Bayesian reasoning to quantum theory (see, for example, the Other uses of Bayesian probability in quantum physics

section below). Consequently, Fuchs chose to call the interpretation

"QBism," pronounced "cubism," preserving the Bayesian spirit via the CamelCase in the first two letters, but distancing it from Bayesianism more broadly. As this neologism is a homonym of Cubism the art movement, it has motivated conceptual comparisons between the two, and media coverage of QBism has been illustrated with art by Picasso and Gris. However, QBism itself was not influenced or motivated by Cubism and has no lineage to a potential connection between Cubist art and Bohr's views on quantum theory.

Core positions

According

to QBism, quantum theory is a tool which an agent may use to help

manage his or her expectations, more like probability theory than a

conventional physical theory.

Quantum theory, QBism claims, is fundamentally a guide for decision

making which has been shaped by some aspects of physical reality. Chief

among the tenets of QBism are the following:

- All probabilities, including those equal to zero or one, are valuations that an agent ascribes to his or her degrees of belief in possible outcomes. As they define and update probabilities, quantum states (density operators), channels (completely positive trace-preserving maps), and measurements (positive operator-valued measures) are also the personal judgements of an agent.

- The Born rule is normative, not descriptive. It is a relation to which an agent should strive to adhere in his or her probability and quantum state assignments.

- Quantum measurement outcomes are personal experiences for the agent gambling on them. Different agents may confer and agree upon the consequences of a measurement, but the outcome is the experience each of them individually has.

- A measurement apparatus is conceptually an extension of the agent. It should be considered analogous to a sense organ or prosthetic limb—simultaneously a tool and a part of the individual.

Reception and criticism

Jean Metzinger, 1912, Danseuse au café. One advocate of QBism, physicist David Mermin,

describes his rationale for choosing that term over the older and more

general "quantum Bayesianism": "I prefer [the] term 'QBist' because

[this] view of quantum mechanics differs from others as radically as

cubism differs from renaissance painting ..."

Reactions to the QBist interpretation have ranged from enthusiastic to strongly negative.

Some who have criticized QBism claim that it fails to meet the goal of

resolving paradoxes in quantum theory. Bacciagaluppi argues that QBism's

treatment of measurement outcomes does not ultimately resolve the issue

of nonlocality,

and Jaeger finds QBism's supposition that the interpretation of

probability is key for the resolution to be unnatural and unconvincing. Norsen has accused QBism of solipsism, and Wallace identifies QBism as an instance of instrumentalism;

QBists have argued insistently that these characterizations are

misunderstandings, and that QBism is neither solipsist nor

instrumentalist. A critical article by Nauenberg in the American Journal of Physics prompted a reply by Fuchs, Mermin, and Schack.

Some assert that there may be inconsistencies; for example, Stairs

argues that when a probability assignment equals one, it cannot be a

degree of belief as QBists say.

Further, while also raising concerns about the treatment of

probability-one assignments, Timpson suggests that QBism may result in a

reduction of explanatory power as compared to other interpretations. Fuchs and Schack replied to these concerns in a later article. Mermin advocated QBism in a 2012 Physics Today article,

which prompted considerable discussion. Several further critiques of

QBism which arose in response to Mermin's article, and Mermin's replies

to these comments, may be found in the Physics Today readers' forum. Section 2 of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on QBism also contains a summary of objections to the interpretation, and some replies.

Others are opposed to QBism on more general philosophical grounds; for

example, Mohrhoff criticizes QBism from the standpoint of Kantian philosophy.

Certain authors find QBism internally self-consistent, but do not subscribe to the interpretation. For example, Marchildon finds QBism well-defined in a way that, to him, many-worlds interpretations are not, but he ultimately prefers a Bohmian interpretation.

Similarly, Schlosshauer and Claringbold state that QBism is a

consistent interpretation of quantum mechanics, but do not offer a

verdict on whether it should be preferred. In addition, some agree with most, but perhaps not all, of the core tenets of QBism; Barnum's position, as well as Appleby's, are examples.

Popularized or semi-popularized media coverage of QBism has appeared in New Scientist, Scientific American, Nature, Science News, the FQXi Community, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Quanta Magazine, Aeon, and Discover. In 2018, two popular-science books about the interpretation of quantum mechanics, Ball's Beyond Weird and Ananthaswamy's Through Two Doors at Once, devote sections to QBism. Furthermore, Harvard University Press published a popularized treatment of the subject, QBism: The Future of Quantum Physics, in 2016.

Relation to other interpretations

Group photo from the 2005 University of Konstanz conference Being Bayesian in a Quantum World.

Copenhagen interpretations

The views of many physicists (Bohr, Heisenberg, Rosenfeld, von Weizsäcker, Peres,

etc.) are often grouped together as the "Copenhagen interpretation" of

quantum mechanics. Several authors have deprecated this terminology,

claiming that it is historically misleading and obscures differences

between physicists that are as important as their similarities.

QBism shares many characteristics in common with the ideas often

labeled as "the Copenhagen interpretation", but the differences are

important; to conflate them or to regard QBism as a minor modification

of the points of view of Bohr or Heisenberg, for instance, would be a

substantial misrepresentation.

QBism takes probabilities to be personal judgments of the

individual agent who is using quantum mechanics. This contrasts with

older Copenhagen-type views, which hold that probabilities are given by

quantum states that are in turn fixed by objective facts about

preparation procedures.

QBism considers a measurement to be any action that an agent takes to

elicit a response from the world and the outcome of that measurement to

be the experience the world's response induces back on that agent. As a

consequence, communication between agents is the only means by which

different agents can attempt to compare their internal experiences.

Most variants of the Copenhagen interpretation, however, hold that the

outcomes of experiments are agent-independent pieces of reality for

anyone to access.

QBism claims that these points on which it differs from previous

Copenhagen-type interpretations resolve the obscurities that many

critics have found in the latter, by changing the role that quantum

theory plays (even though QBism does not yet provide a specific

underlying ontology). Specifically, QBism posits that quantum theory is a normative tool which an agent may use to better navigate reality, rather than a mechanics of reality.

Other epistemic interpretations

Approaches to quantum theory, like QBism,

which treat quantum states as expressions of information, knowledge,

belief, or expectation are called "epistemic" interpretations.

These approaches differ from each other in what they consider quantum

states to be information or expectations "about", as well as in the

technical features of the mathematics they employ. Furthermore, not all

authors who advocate views of this type propose an answer to the

question of what the information represented in quantum states concerns.

In the words of the paper that introduced the Spekkens Toy Model,

...if a quantum state is a state of knowledge, and it is not knowledge of local and noncontextual hidden variables, then what is it knowledge about? We do not at present have a good answer to this question. We shall therefore remain completely agnostic about the nature of the reality to which the knowledge represented by quantum states pertains. This is not to say that the question is not important. Rather, we see the epistemic approach as an unfinished project, and this question as the central obstacle to its completion. Nonetheless, we argue that even in the absence of an answer to this question, a case can be made for the epistemic view. The key is that one can hope to identify phenomena that are characteristic of states of incomplete knowledge regardless of what this knowledge is about.

Leifer

and Spekkens propose a way of treating quantum probabilities as

Bayesian probabilities, thereby considering quantum states as epistemic,

which they state is "closely aligned in its philosophical starting

point" with QBism.

However, they remain deliberately agnostic about what physical

properties or entities quantum states are information (or beliefs)

about, as opposed to QBism, which offers an answer to that question. Another approach, advocated by Bub and Pitowsky, argues that quantum states are information about propositions within event spaces that form non-Boolean lattices. On occasion, the proposals of Bub and Pitowsky are also called "quantum Bayesianism".

Zeilinger

and Brukner have also proposed an interpretation of quantum mechanics

in which "information" is a fundamental concept, and in which quantum

states are epistemic quantities.

Unlike QBism, the Brukner–Zeilinger interpretation treats some

probabilities as objectively fixed. In the Brukner–Zeilinger

interpretation, a quantum state represents the information that a

hypothetical observer in possession of all possible data would have. Put

another way, a quantum state belongs in their interpretation to an optimally-informed agent, whereas in QBism, any agent can formulate a state to encode her own expectations.

Despite this difference, in Cabello's classification, the proposals of

Zeilinger and Brukner are also designated as "participatory realism," as

QBism and the Copenhagen-type interpretations are.

Bayesian, or epistemic, interpretations of quantum probabilities were proposed in the early 1990s by Baez and Youssef.

Von Neumann's views

R. F. Streater argued that "[t]he first quantum Bayesian was von Neumann," basing that claim on von Neumann's textbook The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics.

Blake Stacey disagrees, arguing that the views expressed in that book

on the nature of quantum states and the interpretation of probability

are not compatible with QBism, or indeed, with any position that might

be called quantum Bayesianism.

Relational quantum mechanics

Comparisons have also been made between QBism and the relational quantum mechanics (RQM) espoused by Carlo Rovelli and others. In both QBism and RQM, quantum states are not intrinsic properties of physical systems.

Both QBism and RQM deny the existence of an absolute, universal

wavefunction. Furthermore, both QBism and RQM insist that quantum

mechanics is a fundamentally local theory.

In addition, Rovelli, like several QBist authors, advocates

reconstructing quantum theory from physical principles in order to bring

clarity to the subject of quantum foundations.

One important distinction between the two interpretations is their

philosophy of probability: RQM does not adopt the Ramsey–de Finetti

school of personalist Bayesianism. Moreover, RQM does not insist that a measurement outcome is necessarily an agent's experience.

Other uses of Bayesian probability in quantum physics

QBism should be distinguished from other applications of Bayesian inference in quantum physics, and from quantum analogues of Bayesian inference. For example, some in the field of computer science have introduced a kind of quantum Bayesian network, which they argue could have applications in "medical diagnosis, monitoring of processes, and genetics". Bayesian inference has also been applied in quantum theory for updating probability densities over quantum states, and MaxEnt methods have been used in similar ways. Bayesian methods for quantum state and process tomography are an active area of research.

Technical developments and reconstructing quantum theory

Conceptual

concerns about the interpretation of quantum mechanics and the meaning

of probability have motivated technical work. A quantum version of the de Finetti theorem, introduced by Caves, Fuchs, and Schack (independently reproving a result found using different means by Størmer) to provide a Bayesian understanding of the idea of an "unknown quantum state", has found application elsewhere, in topics like quantum key distribution and entanglement detection.

Adherents of several interpretations of quantum mechanics, QBism

included, have been motivated to reconstruct quantum theory. The goal of

these research efforts has been to identify a new set of axioms or

postulates from which the mathematical structure of quantum theory can

be derived, in the hope that with such a reformulation, the features of

nature which made quantum theory the way it is might be more easily

identified. Although the core tenets of QBism do not demand such a reconstruction, some QBists—Fuchs, in particular—have argued that the task should be pursued.

One topic prominent in the reconstruction effort is the set of

mathematical structures known as symmetric, informationally-complete,

positive operator-valued measures (SIC-POVMs).

QBist foundational research stimulated interest in these structures,

which now have applications in quantum theory outside of foundational

studies and in pure mathematics.

The most extensively explored QBist reformulation of quantum

theory involves the use of SIC-POVMs to rewrite quantum states (either

pure or mixed) as a set of probabilities defined over the outcomes of a "Bureau of Standards" measurement. That is, if one expresses a density matrix

as a probability distribution over the outcomes of a SIC-POVM

experiment, one can reproduce all the statistical predictions implied by

the density matrix from the SIC-POVM probabilities instead. The Born rule

then takes the role of relating one valid probability distribution to

another, rather than of deriving probabilities from something apparently

more fundamental. Fuchs, Schack and others have taken to calling this

restatment of the Born rule the urgleichung, from the German for "primal equation" (see Ur- prefix), because of the central role it plays in their reconstruction of quantum theory.

The following discussion presumes some familiarity with the mathematics of quantum information theory, and in particular, the modeling of measurement procedures by POVMs. Consider a quantum system to which is associated a -dimensional Hilbert space. If a set of rank-1 projectors satisfying

exists, then one may form a SIC-POVM . An arbitrary quantum state may be written as a linear combination of the SIC projectors

where is the Born rule probability for obtaining SIC measurement outcome implied by the state assignment .

We follow the convention that operators have hats while experiences

(that is, measurement outcomes) do not. Now consider an arbitrary

quantum measurement, denoted by the POVM . The urgleichung is the expression obtained from forming the Born rule probabilities, , for the outcomes of this quantum measurement,

where is the Born rule probability for obtaining outcome implied by the state assignment . The

term may be understood to be a conditional probability in a cascaded

measurement scenario: Imagine that an agent plans to perform two

measurements, first a SIC measurement and then the

measurement. After obtaining an outcome from the SIC measurement, the

agent will update her state assignment to a new quantum state before performing the second measurement. If she uses the Lüders rule for state update and obtains outcome from the SIC measurement, then . Thus the probability for obtaining outcome for the second measurement conditioned on obtaining outcome for the SIC measurement is .

Note that the urgleichung is structurally very similar to the law of total probability, which is the expression

They functionally differ only by a dimension-dependent affine transformation

of the SIC probability vector. As QBism says that quantum theory is an

empirically-motivated normative addition to probability theory, Fuchs

and others find the appearance of a structure in quantum theory

analogous to one in probability theory to be an indication that a

reformulation featuring the urgleichung prominently may help to reveal

the properties of nature which made quantum theory so successful.

It is important to recognize that the urgleichung does not replace the law of total probability. Rather, the urgleichung and the law of total probability apply in different scenarios because and refer to different situations. is the probability that an agent assigns for obtaining outcome on her second of two planned measurements, that is, for obtaining outcome after first making the SIC measurement and obtaining one of the outcomes. , on the other hand, is the probability an agent assigns for obtaining outcome when she does not plan to first make the SIC measurement. The law of total probability is a consequence of coherence

within the operational context of performing the two measurements as

described. The urgleichung, in contrast, is a relation between different

contexts which finds its justification in the predictive success of

quantum physics.

The SIC representation of quantum states also provides a reformulation of quantum dynamics. Consider a quantum state with SIC representation . The time evolution of this state is found by applying a unitary operator to form the new state , which has the SIC representation

The second equality is written in the Heisenberg picture

of quantum dynamics, with respect to which the time evolution of a

quantum system is captured by the probabilities associated with a

rotated SIC measurement of the original quantum state . Then the Schrödinger equation is completely captured in the urgleichung for this measurement:

In

these terms, the Schrödinger equation is an instance of the Born rule

applied to the passing of time; an agent uses it to relate how she will

gamble on informationally complete measurements potentially performed at

different times.

Those QBists who find this approach promising are pursuing a

complete reconstruction of quantum theory featuring the urgleichung as

the key postulate. (The urgleichung has also been discussed in the context of category theory.)

Comparisons between this approach and others not associated with QBism

(or indeed with any particular interpretation) can be found in a book

chapter by Fuchs and Stacey and an article by Appleby et al. As of 2017, alternative QBist reconstruction efforts are in the beginning stages.

![{\displaystyle {\hat {\rho }}=\sum _{i=1}^{d^{2}}\left[(d+1)P(H_{i})-{\frac {1}{d}}\right]{\hat {\Pi }}_{i},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5f5c8d6d6bb46296ba035fa30604572bfd2261a)

![{\displaystyle Q(D_{j})=\sum _{i=1}^{d^{2}}\left[(d+1)P(H_{i})-{\frac {1}{d}}\right]P(D_{j}\mid H_{i}),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ddfb1738aaf31b5500021523c8405853e7a4800c)

![{\displaystyle P_{t}(H_{i})=\operatorname {tr} \left[({\hat {U}}{\hat {\rho }}{\hat {U}}^{\dagger }){\hat {H}}_{i}\right]=\operatorname {tr} \left[{\hat {\rho }}({\hat {U}}^{\dagger }{\hat {H}}_{i}{\hat {U}})\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2e27955da58e172f918b160e0a0dbd3ea44ad17c)

![{\displaystyle P_{t}(H_{j})=\sum _{i=1}^{d^{2}}\left[(d+1)P(H_{i})-{\frac {1}{d}}\right]P(D_{j}\mid H_{i}).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a03bce466c6694c638e29504c52cf43ef961d728)