Quantum machine learning is an emerging interdisciplinary research area at the intersection of quantum physics and machine learning. The most common use of the term refers to machine learning algorithms for the analysis of classical data executed on a quantum computer. While machine learning algorithms are used to compute immense quantities of data, quantum machine learning increases such capabilities intelligently, by creating opportunities to conduct analysis on quantum states and systems. This includes hybrid methods that involve both classical and quantum processing, where computationally difficult subroutines are outsourced to a quantum device. These routines can be more complex in nature and executed faster with the assistance of quantum devices. Furthermore, quantum algorithms can be used to analyze quantum states instead of classical data. Beyond quantum computing, the term "quantum machine learning" is often associated with machine learning methods applied to data generated from quantum experiments, such as learning quantum phase transitions or creating new quantum experiments. Quantum machine learning also extends to a branch of research that explores methodological and structural similarities between certain physical systems and learning systems, in particular neural networks. For example, some mathematical and numerical techniques from quantum physics are applicable to classical deep learning and vice versa. Finally, researchers investigate more abstract notions of learning theory with respect to quantum information, sometimes referred to as "quantum learning theory".

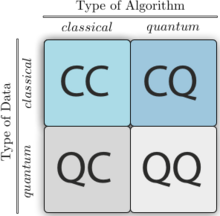

Four different approaches to combine the disciplines of quantum computing and machine learning.

The first letter refers to whether the system under study is classical

or quantum, while the second letter defines whether a classical or

quantum information processing device is used.

Machine learning with quantum computers

Quantum-enhanced machine learning refers to quantum algorithms

that solve tasks in machine learning, thereby improving and often

expediting classical machine learning techniques. Such algorithms

typically require one to encode the given classical data set into a

quantum computer to make it accessible for quantum information

processing. Subsequently, quantum information processing routines are

applied and the result of the quantum computation is read out by

measuring the quantum system. For example, the outcome of the

measurement of a qubit reveals the result of a binary classification

task. While many proposals of quantum machine learning algorithms are

still purely theoretical and require a full-scale universal quantum computer to be tested, others have been implemented on small-scale or special purpose quantum devices.

Linear algebra simulation with quantum amplitudes

A number of quantum algorithms for machine learning are based on the idea of amplitude encoding, that is, to associate the amplitudes of a quantum state with the inputs and outputs of computations. Since a state of qubits is described by

complex amplitudes, this information encoding can allow for an

exponentially compact representation. Intuitively, this corresponds to

associating a discrete probability distribution over binary random

variables with a classical vector. The goal of algorithms based on

amplitude encoding is to formulate quantum algorithms whose resources

grow polynomially in the number of qubits , which amounts to a logarithmic growth in the number of amplitudes and thereby the dimension of the input.

Many quantum machine learning algorithms in this category are based on variations of the quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations

(colloquially called HHL, after the paper's authors) which, under

specific conditions, performs a matrix inversion using an amount of

physical resources growing only logarithmically in the dimensions of the

matrix. One of these conditions is that a Hamiltonian which entrywise

corresponds to the matrix can be simulated efficiently, which is known

to be possible if the matrix is sparse or low rank. For reference, any known classical algorithm for matrix inversion requires a number of operations that grows at least quadratically in the dimension of the matrix.

Quantum matrix inversion can be applied to machine learning methods in which the training reduces to solving a linear system of equations, for example in least-squares linear regression, the least-squares version of support vector machines, and Gaussian processes.

A crucial bottleneck of methods that simulate linear algebra

computations with the amplitudes of quantum states is state preparation,

which often requires one to initialise a quantum system in a state

whose amplitudes reflect the features of the entire dataset. Although

efficient methods for state preparation are known for specific cases, this step easily hides the complexity of the task.

Quantum machine learning algorithms based on Grover search

Another approach to improving classical machine learning with quantum information processing uses amplitude amplification methods based on Grover's search

algorithm, which has been shown to solve unstructured search problems

with a quadratic speedup compared to classical algorithms. These quantum

routines can be employed for learning algorithms that translate into an

unstructured search task, as can be done, for instance, in the case of

the k-medians and the k-nearest neighbors algorithms. Another application is a quadratic speedup in the training of perceptron.

Amplitude amplification is often combined with quantum walks to achieve the same quadratic speedup. Quantum walks have been proposed to enhance Google's PageRank algorithm as well as the performance of reinforcement learning agents in the projective simulation framework.

Quantum-enhanced reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning is a branch of machine learning distinct from supervised and unsupervised learning, which also admits quantum enhancements.

In quantum-enhanced reinforcement learning, a quantum agent interacts

with a classical environment and occasionally receives rewards for its

actions, which allows the agent to adapt its behavior—in other words, to

learn what to do in order to gain more rewards. In some situations,

either because of the quantum processing capability of the agent, or due to the possibility to probe the environment in superpositions, a quantum speedup may be achieved. Implementations of these kinds of protocols in superconducting circuits and in systems of trapped ions have been proposed.

Quantum annealing

Quantum annealing

is an optimization technique used to determine the local minima and

maxima of a function over a given set of candidate functions. This is a

method of discretizing a function with many local minima or maxima in

order to determine the observables of the function. The process can be

distinguished from Simulated annealing by the Quantum tunneling

process, by which particles tunnel through kinetic or potential

barriers from a high state to a low state. Quantum annealing starts from

a superposition of all possible states of a system, weighted equally.

Then the time-dependent Schrödinger equation

guides the time evolution of the system, serving to affect the

amplitude of each state as time increases. Eventually, the ground state

can be reached to yield the instantaneous Hamiltonian of the system.

Quantum sampling techniques

Sampling

from high-dimensional probability distributions is at the core of a

wide spectrum of computational techniques with important applications

across science, engineering, and society. Examples include deep learning, probabilistic programming, and other machine learning and artificial intelligence applications.

A computationally hard problem, which is key for some relevant

machine learning tasks, is the estimation of averages over probabilistic

models defined in terms of a Boltzmann distribution.

Sampling from generic probabilistic models is hard: algorithms relying

heavily on sampling are expected to remain intractable no matter how

large and powerful classical computing resources become. Even though quantum annealers,

like those produced by D-Wave Systems, were designed for challenging

combinatorial optimization problems, it has been recently recognized as a

potential candidate to speed up computations that rely on sampling by

exploiting quantum effects.

Some research groups have recently explored the use of quantum annealing hardware for training Boltzmann machines and deep neural networks.

The standard approach to training Boltzmann machines relies on the

computation of certain averages that can be estimated by standard sampling techniques, such as Markov chain Monte Carlo

algorithms. Another possibility is to rely on a physical process, like

quantum annealing, that naturally generates samples from a Boltzmann

distribution. The objective is to find the optimal control parameters

that best represent the empirical distribution of a given dataset.

The D-Wave 2X system hosted at NASA Ames Research Center has been

recently used for the learning of a special class of restricted

Boltzmann machines that can serve as a building block for deep learning

architectures.

Complementary work that appeared roughly simultaneously showed that

quantum annealing can be used for supervised learning in classification

tasks.

The same device was later used to train a fully connected Boltzmann

machine to generate, reconstruct, and classify down-scaled,

low-resolution handwritten digits, among other synthetic datasets.

In both cases, the models trained by quantum annealing had a similar or

better performance in terms of quality. The ultimate question that

drives this endeavour is whether there is quantum speedup in sampling

applications. Experience with the use of quantum annealers for

combinatorial optimization suggests the answer is not straightforward.

Inspired by the success of Boltzmann machines based on classical

Boltzmann distribution, a new machine learning approach based on quantum

Boltzmann distribution of a transverse-field Ising Hamiltonian was

recently proposed.

Due to the non-commutative nature of quantum mechanics, the training

process of the quantum Boltzmann machine can become nontrivial. This

problem was, to some extent, circumvented by introducing bounds on the

quantum probabilities, allowing the authors to train the model

efficiently by sampling. It is possible that a specific type of quantum

Boltzmann machine has been trained in the D-Wave 2X by using a learning

rule analogous to that of classical Boltzmann machines.

Quantum annealing

is not the only technology for sampling. In a prepare-and-measure

scenario, a universal quantum computer prepares a thermal state, which

is then sampled by measurements. This can reduce the time required to

train a deep restricted Boltzmann machine, and provide a richer and more

comprehensive framework for deep learning than classical computing.

The same quantum methods also permit efficient training of full

Boltzmann machines and multi-layer, fully connected models and do not

have well-known classical counterparts. Relying on an efficient thermal

state preparation protocol starting from an arbitrary state,

quantum-enhanced Markov logic networks exploit the symmetries and the locality structure of the probabilistic graphical model generated by a first-order logic template.

This provides an exponential reduction in computational complexity in

probabilistic inference, and, while the protocol relies on a universal

quantum computer, under mild assumptions it can be embedded on

contemporary quantum annealing hardware.

Quantum neural networks

Quantum analogues or generalizations of classical neural nets are often referred to as quantum neural networks.

The term is claimed by a wide range of approaches, including the

implementation and extension of neural networks using photons, layered

variational circuits or quantum Ising-type models. Quantum neural

networks are often defined as an expansion on Deutsch's model of a

quantum computational network.

Within this model, nonlinear and irreversible gates, dissimilar to the

Hamiltonian operator, are deployed to speculate the given data set. Such gates make certain phases unable to be observed and generate specific oscillations. Quantum neural networks apply the principals quantum information and quantum computation to classical neurocomputing.

Current research shows that QNN can exponentially increase the amount

of computing power and the degrees of freedom for a computer, which is

limited for a classical computer to its size. A quantum neural network has computational capabilities to decrease the number of steps, qubits used, and computation time.

The wave function to quantum mechanics is the neuron for Neural

networks. To test quantum applications in a neural network, quantum dot

molecules are deposited on a substrate of GaAs or similar to record how

they communicate with one another. Each quantum dot can be referred as

an island of electric activity, and when such dots are close enough

(approximately 10±20 nm)

electrons can tunnel underneath the islands. An even distribution

across the substrate in sets of two create dipoles and ultimately two

spin states, up or down. These states are commonly known as qubits with

corresponding states of |0> and |1> in Dirac notation.

Hidden Quantum Markov Models

Hidden Quantum Markov Models (HQMMs) are a quantum-enhanced version of classical Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), which are typically used to model sequential data in various fields like robotics and natural language processing.

Unlike the approach taken by other quantum-enhanced machine learning

algorithms, HQMMs can be viewed as models inspired by quantum mechanics

that can be run on classical computers as well. Where classical HMMs use probability vectors to represent hidden 'belief' states, HQMMs use the quantum analogue: density matrices.

Recent work has shown that these models can be successfully learned by

maximizing the log-likelihood of the given data via classical

optimization, and there is some empirical evidence that these models can

better model sequential data compared to classical HMMs in practice,

although further work is needed to determine exactly when and how these

benefits are derived. Additionally, since classical HMMs are a particular kind of Bayes net, an exciting aspect of HQMMs is that the techniques used show how we can perform quantum-analogous Bayesian inference, which should allow for the general construction of the quantum versions of probabilistic graphical models.

Fully quantum machine learning

In

the most general case of quantum machine learning, both the learning

device and the system under study, as well as their interaction, are

fully quantum. This section gives a few examples of results on this

topic.

One class of problem that can benefit from the fully quantum

approach is that of 'learning' unknown quantum states, processes or

measurements, in the sense that one can subsequently reproduce them on

another quantum system. For example, one may wish to learn a measurement

that discriminates between two coherent states, given not a classical

description of the states to be discriminated, but instead a set of

example quantum systems prepared in these states. The naive approach

would be to first extract a classical description of the states and then

implement an ideal discriminating measurement based on this

information. This would only require classical learning. However, one

can show that a fully quantum approach is strictly superior in this

case. (This also relates to work on quantum pattern matching.) The problem of learning unitary transformations can be approached in a similar way.

Going beyond the specific problem of learning states and transformations, the task of clustering

also admits a fully quantum version, wherein both the oracle which

returns the distance between data-points and the information processing

device which runs the algorithm are quantum.

Finally, a general framework spanning supervised, unsupervised and

reinforcement learning in the fully quantum setting was introduced in,

where it was also shown that the possibility of probing the environment

in superpositions permits a quantum speedup in reinforcement learning.

Classical learning applied to quantum problems

The

term quantum machine learning is also used for approaches that apply

classical methods of machine learning to the study of quantum systems. A

prime example is the use of classical learning techniques to process

large amounts of experimental or calculated (for example by solving Schrodinger's equation data in order to characterize an unknown quantum system (for instance in the context of quantum information theory

and for the development of quantum technologies or computational

materials design), but there are also more exotic applications.

Noisy data

The

ability to experimentally control and prepare increasingly complex

quantum systems brings with it a growing need to turn large and noisy

data sets into meaningful information. This is a problem that has

already been studied extensively in the classical setting, and

consequently, many existing machine learning techniques can be naturally

adapted to more efficiently address experimentally relevant problems.

For example, Bayesian methods and concepts of algorithmic learning can be fruitfully applied to tackle quantum state classification, Hamiltonian learning, and the characterization of an unknown unitary transformation. Other problems that have been addressed with this approach are given in the following list:

- Identifying an accurate model for the dynamics of a quantum system, through the reconstruction of the Hamiltonian;

- Extracting information on unknown states;

- Learning unknown unitary transformations and measurements;

- Engineering of quantum gates from qubit networks with pairwise interactions, using time dependent or independent Hamiltonians.

Calculated and noise-free data

Quantum

machine learning can also be applied to dramatically accelerate the

prediction of quantum properties of molecules and materials. This can be helpful for the computational design of new molecules or materials. Some examples include

- Interpolating interatomic potentials;

- Inferring molecular atomization energies throughout chemical compound space;

- Accurate potential energy surfaces with restricted Boltzmann machines;

- Automatic generation of new quantum experiments;

- Solving the many-body, static and time-dependent Schrödinger equation;

- Identifying phase transitions from entanglement spectra;

- Generating adaptive feedback schemes for quantum metrology.

Variational Circuits

Variational circuits are a family of algorithms which utilize training based on circuit parameters and an objective function.

Variational circuits are generally composed of a classical device

communicating input parameters (random or pre-trained parameters) into a

quantum device, along with a classical Mathematical optimization

function. These circuits are very heavily dependent on the architecture

of the proposed quantum device because parameter adjustments are

adjusted based solely on the classical components within the device.

Though the application is considerably infantile in the field of

quantum machine learning, it has incredibly high promise for more

efficiently generating efficient optimization functions.

Quantum learning theory

Quantum

learning theory pursues a mathematical analysis of the quantum

generalizations of classical learning models and of the possible

speed-ups or other improvements that they may provide. The framework is

very similar to that of classical computational learning theory,

but the learner in this case is a quantum information processing

device, while the data may be either classical or quantum. Quantum

learning theory should be contrasted with the quantum-enhanced machine

learning discussed above, where the goal was to consider specific problems

and to use quantum protocols to improve the time complexity of

classical algorithms for these problems. Although quantum learning

theory is still under development, partial results in this direction

have been obtained.

The starting point in learning theory is typically a concept class, a set of possible concepts. Usually a concept is a function on some domain, such as . For example, the concept class could be the set of disjunctive normal form (DNF) formulas on n bits or the set of Boolean circuits of some constant depth. The goal for the learner is to learn

(exactly or approximately) an unknown target concept from this

concept class. The learner may be actively interacting with the target

concept, or passively receiving samples from it.

In active learning, a learner can make membership queries to the target concept c, asking for its value c(x) on inputs x chosen by the learner. The learner then has to reconstruct the exact target concept, with high probability. In the model of quantum exact learning,

the learner can make membership queries in quantum superposition. If

the complexity of the learner is measured by the number of membership

queries it makes, then quantum exact learners can be polynomially more

efficient than classical learners for some concept classes, but not

more. If complexity is measured by the amount of time

the learner uses, then there are concept classes that can be learned efficiently by

quantum learners but not by classical learners (under plausible complexity-theoretic assumptions).

A natural model of passive learning is Valiant's probably approximately correct (PAC) learning. Here the learner receives random examples (x,c(x)), where x is distributed according to some unknown distribution D. The learner's goal is to output a hypothesis function h such that h(x)=c(x) with high probability when x is drawn according to D. The learner has to be able to produce such an 'approximately correct' h for every D and every target concept c in its concept class.

We can consider replacing the random examples by potentially more powerful quantum examples .

In the PAC model (and the related agnostic model), this doesn't

significantly reduce the number of examples needed: for every concept

class, classical and

quantum sample complexity are the same up to constant factors. However, for learning under some

fixed distribution D, quantum examples can be very helpful, for example for learning DNF under

the uniform distribution. When considering time

complexity, there exist concept classes that can be PAC-learned

efficiently by quantum learners, even from classical examples, but not

by classical learners (again, under plausible complexity-theoretic

assumptions).

This passive learning type is also the most common scheme in

supervised learning: a learning algorithm typically takes the training

examples fixed, without the ability to query the label of unlabelled

examples. Outputting a hypothesis h is a step of induction.

Classically, an inductive model splits into a training and an

application phase: the model parameters are estimated in the training

phase, and the learned model is applied an arbitrary many times in the

application phase. In the asymptotic limit of the number of

applications, this splitting of phases is also present with quantum

resources.

Implementations and experiments

The earliest experiments were conducted using the adiabatic D-Wave

quantum computer, for instance, to detect cars in digital images using

regularized boosting with a nonconvex objective function in a

demonstration in 2009.

Many experiments followed on the same architecture, and leading tech

companies have shown interest in the potential of quantum machine

learning for future technological implementations. In 2013, Google

Research, NASA, and the Universities Space Research Association launched the Quantum Artificial Intelligence Lab which explores the use of the adiabatic D-Wave quantum computer.

A more recent example trained a probabilistic generative models with

arbitrary pairwise connectivity, showing that their model is capable of

generating handwritten digits as well as reconstructing noisy images of

bars and stripes and handwritten digits.

Using a different annealing technology based on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), a quantum Hopfield network

was implemented in 2009 that mapped the input data and memorized data

to Hamiltonians, allowing the use of adiabatic quantum computation. NMR technology also enables universal quantum computing,

and it was used for the first experimental implementation of a quantum

support vector machine to distinguish hand written number ‘6’ and ‘9’ on

a liquid-state quantum computer in 2015.

The training data involved the pre-processing of the image which maps

them to normalized 2-dimensional vectors to represent the images as the

states of a qubit. The two entries of the vector are the vertical and

horizontal ratio of the pixel intensity of the image. Once the vectors

are defined on the feature space, the quantum support vector machine was

implemented to classify the unknown input vector. The readout avoids

costly quantum tomography by reading out the final state in terms of direction (up/down) of the NMR signal.

Photonic implementations are attracting more attention,

not the least because they do not require extensive cooling.

Simultaneous spoken digit and speaker recognition and chaotic

time-series prediction were demonstrated at data rates beyond 1 gigabyte

per second in 2013.

Using non-linear photonics to implement an all-optical linear

classifier, a perceptron model was capable of learning the

classification boundary iteratively from training data through a

feedback rule.

A core building block in many learning algorithms is to calculate the

distance between two vectors: this was first experimentally demonstrated

for up to eight dimensions using entangled qubits in a photonic quantum

computer in 2015.

Recently, based on a neuromimetic approach, a novel ingredient

has been added to the field of quantum machine learning, in the form of a

so-called quantum memristor, a quantized model of the standard

classical memristor.

This device can be constructed by means of a tunable resistor, weak

measurements on the system, and a classical feed-forward mechanism. An

implementation of a quantum memristor in superconducting circuits has

been proposed, and an experiment with quantum dots performed.

A quantum memristor would implement nonlinear interactions in the

quantum dynamics which would aid the search for a fully functional quantum neural network.

Since 2016, IBM has launced on online cloud-based platform for quantum software developers, called the IBM Q Experience.

This platform consists of several fully operational quantum processors

accessible via the IBM Web API. In doing so, the company is encouraging

software developers to pursue new algorithms through a development

environment with quantum capabilities. New architectures are being

explored on an experimental basis, up to 32 qbits, utilizing both

trapped-ion and superconductive quantum computing methods.