Reservoir glass with naturally coloured verte absinthe and an absinthe spoon

| |

| Type | Spirit |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Switzerland |

| Alcohol by volume | 45–74% |

| Proof (US) | 90–148 |

| Colour | Green |

| Flavour | Anise |

| Ingredients | |

Albert Maignan's Green Muse (1895): a poet succumbs to the Green Fairy

An absinthe frappé, a common way to serve absinthe with simple syrup, water, and crushed ice

Absinthe is historically described as a distilled, highly alcoholic beverage (45–74% ABV / 90–148 U.S. proof). It is an anise-flavoured spirit derived from botanicals, including the flowers and leaves of Artemisia absinthium ("grand wormwood"), together with green anise, sweet fennel, and other medicinal and culinary herbs.

Absinthe traditionally has a natural green colour, but may also

be colourless. It is commonly referred to in historical literature as "la fée verte"

(the green fairy). It is sometimes mistakenly referred to as a liqueur,

but it is not traditionally bottled with added sugar and is, therefore,

classified as a spirit.

Absinthe is traditionally bottled at a high level of alcohol by volume,

but it is normally diluted with water prior to being consumed.

Absinthe originated in the canton of Neuchâtel

in Switzerland in the late 18th century. It rose to great popularity as

an alcoholic drink in late 19th- and early 20th-century France,

particularly among Parisian artists and writers. The consumption of

absinthe was opposed by social conservatives and prohibitionists, partly

due to its association with bohemian culture. Absinthe drinkers included Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, Oscar Wilde, Marcel Proust, Aleister Crowley, Erik Satie, Edgar Allan Poe, Lord Byron and Alfred Jarry.

Absinthe has often been portrayed as a dangerously addictive psychoactive drug and hallucinogen. The chemical compound thujone,

which is present in the spirit in trace amounts, was blamed for its

alleged harmful effects. By 1915, absinthe had been banned in the United

States and in much of Europe, including France, the Netherlands,

Belgium, Switzerland, and Austria-Hungary, yet it has not been

demonstrated to be any more dangerous than ordinary spirits. Recent

studies have shown that absinthe's psychoactive properties have been

exaggerated, apart from that of the alcohol.

A revival of absinthe began in the 1990s following the adoption

of modern European Union food and beverage laws which removed

long-standing barriers to its production and sale. By the early 21st

century, nearly 200 brands of absinthe were being produced in a dozen

countries, most notably in France, Switzerland, Austria, Germany,

Netherlands, Spain, and the Czech Republic.

Etymology

The French word absinthe can refer either to the alcoholic beverage or, less commonly, to the actual wormwood plant, with grande absinthe being Artemisia absinthium, and petite absinthe being Artemisia pontica. The Latin name artemisia comes from the Greek ἀρτεμισία "wormwood" and the latter from Artemis, the ancient Greek goddess of the hunt. Absinthe is derived from the Latin absinthium, which in turn comes from the Greek ἀψίνθιον apsínthion, "wormwood". The use of Artemisia absinthium in a drink is attested in Lucretius' De Rerum Natura

(I 936–950), where Lucretius indicates that a drink containing wormwood

is given as medicine to children in a cup with honey on the brim to

make it drinkable. Some claim that the word means "undrinkable" in Greek, but it may instead be linked to the Persian root spand or aspand, or the variant esfand, which meant Peganum harmala, also called Syrian Rue—although it is not actually a variety of rue, another famously bitter herb. That Artemisia absinthium was commonly burned as a protective offering may suggest that its origins lie in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root *spend,

meaning "to perform a ritual" or "make an offering". Whether the word

was a borrowing from Persian into Greek, or from a common ancestor of

both, is unclear. Alternatively, the Greek word may originate in a pre-Greek substrate word, marked by the non-Indo-European consonant complex νθ (-nth). Alternative spellings for absinthe include absinth, absynthe and absenta. Absinth (without the final e)

is a spelling variant most commonly applied to absinthes produced in

central and eastern Europe, and is specifically associated with Bohemian-style absinthes.

History

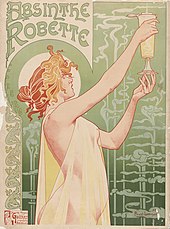

Henri Privat-Livemont's 1896 poster

The precise origin of absinthe is unclear. The medical use of wormwood dates back to ancient Egypt and is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus,

c. 1550 BC. Wormwood extracts and wine-soaked wormwood leaves were used

as remedies by the ancient Greeks. Moreover, there is evidence of a

wormwood-flavoured wine in ancient Greece called absinthites oinos.

The first evidence of absinthe dates to the 18th century in the

sense of a distilled spirit containing green anise and fennel. According

to popular legend, it began as an all-purpose patent remedy created by

Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Couvet,

Switzerland around 1792 (the exact date varies by account). Ordinaire's

recipe was passed on to the Henriod sisters of Couvet, who sold it as a

medicinal elixir. By other accounts, the Henriod sisters may have been

making the elixir before Ordinaire's arrival. In either case, a certain

Major Dubied acquired the formula from the sisters in 1797 and opened

the first absinthe distillery named Dubied Père et Fils in Couvet with

his son Marcellin and son-in-law Henry-Louis Pernod. In 1805, they built

a second distillery in Pontarlier, France under the company name Maison

Pernod Fils. Pernod Fils remained one of the most popular brands of absinthe until the drink was banned in France in 1914.

Growth of consumption

An advertising poster for Absinthe Beucler

Absinthe's popularity grew steadily through the 1840s, when it was given to French troops as a malaria preventive,

and the troops brought home their taste for it. Absinthe became so

popular in bars, bistros, cafés, and cabarets by the 1860s that the hour

of 5 p.m. was called l'heure verte ("the green hour"). It was

favoured by all social classes, from the wealthy bourgeoisie to poor

artists and ordinary working-class people. By the 1880s, mass production

had caused the price to drop sharply, and the French were drinking 36

million litres per year by 1910, compared to their annual consumption of

almost 5 billion litres of wine.

Absinthe was exported widely from France and Switzerland and

attained some degree of popularity in other countries, including Spain,

Great Britain, USA, and the Czech Republic. It was never banned in Spain

or Portugal, and its production and consumption have never ceased. It

gained a temporary spike in popularity there during the early 20th

century, corresponding with the Art Nouveau and Modernism aesthetic

movements.

New Orleans has a cultural association with absinthe and is credited as the birthplace of the Sazerac, perhaps the earliest absinthe cocktail. The Old Absinthe House bar on Bourbon Street sold absinthe since the first half of the 19th century. Its Catalan lease-holder Cayetano Ferrer named it the Absinthe Room in 1874 because of the popularity of the drink, which was served in the Parisian style. It was frequented by Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Aleister Crowley, and Frank Sinatra.

Bans

Absinthe

became associated with violent crimes and social disorder, and one

modern writer claims that this trend was spurred by fabricated claims

and smear campaigns, which he claims were orchestrated by the temperance

movement and the wine industry. One critic claimed:

Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal, provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country.

L'Absinthe, by Edgar Degas, 1876

Edgar Degas's 1876 painting L'Absinthe can be seen at the Musée d'Orsay epitomising the popular view of absinthe addicts as sodden and benumbed, and Émile Zola described its effects in his novel L'Assommoir. Swiss farmer Jean Lanfray

murdered his family in 1905 and attempted to take his own life after

drinking absinthe. Lanfray was an alcoholic who had consumed

considerable quantities of wine and brandy prior to drinking two glasses

of absinthe, but that was overlooked or ignored, placing the blame for

the murders solely on absinthe.

The Lanfray murders were the tipping point in this hotly debated topic,

and a subsequent petition collected more than 82,000 signatures to ban

it in Switzerland. A referendum was held on 5 July 1908. It was approved by voters, and the prohibition of absinthe was written into the Swiss constitution.

In 1906, Belgium and Brazil banned the sale and distribution of

absinthe, although these were not the first countries to take such

action. It had been banned as early as 1898 in the colony of the Congo Free State. The Netherlands banned it in 1909, Switzerland in 1910, the United States in 1912, and France in 1914.

The prohibition of absinthe in France would eventually lead to the popularity of pastis, and to a lesser extent, ouzo,

and other anise-flavoured spirits that do not contain wormwood.

Following the conclusion of the First World War, production of the

Pernod Fils brand was resumed at the Banus distillery in Catalonia, Spain (where absinthe was still legal), but gradually declining sales saw the cessation of production in the 1960s. In Switzerland, the ban served only to drive the production of absinthe underground. Clandestine home distillers produced colourless absinthe (la Bleue),

which was easier to conceal from the authorities. Many countries never

banned absinthe, notably Britain, where it had never been as popular as

in continental Europe.

Modern revival

British importer BBH Spirits began to import Hill's Absinth

from the Czech Republic in the 1990s, as the UK had never formally

banned it, and this sparked a modern resurgence in its popularity. It

began to reappear during a revival in the 1990s in countries where it

was never banned. Forms of absinthe available during that time consisted

almost exclusively of Czech, Spanish, and Portuguese brands that were

of recent origin, typically consisting of Bohemian-style products. Connoisseurs considered these of inferior quality and not representative of the 19th century spirit. In 2000, La Fée Absinthe became the first commercial absinthe distilled and bottled in France since the 1914 ban, but it is now one of dozens of brands that are produced and sold within France.

Modern absinthes. Vertes at left; blanches at right. A prepared glass is in front of each.

In the Netherlands, the restrictions were challenged by Amsterdam

wineseller Menno Boorsma in July 2004, thus confirming the legality of

absinthe once again. Similarly, Belgium lifted its long-standing ban on

January 1, 2005, citing a conflict with the adopted food and beverage

regulations of the Single European Market. In Switzerland, the

constitutional ban was repealed in 2000 during an overhaul of the

national constitution, although the prohibition was written into

ordinary law instead. That law was later repealed and it was made legal

on March 1, 2005.

The drink was never officially banned in Spain, although it began

to fall out of favour in the 1940s and almost vanished into obscurity.

The Catalan region has seen significant resurgence since 2007 when one

producer established operations there. Absinthe has never been illegal

to import or manufacture in Australia,

although importation requires a permit under the Customs (Prohibited

Imports) Regulation 1956 due to a restriction on importing any product

containing "oil of wormwood". In 2000, an amendment made all wormwood species prohibited herbs for food purposes under Food Standard 1.4.4. Prohibited and Restricted Plants and Fungi. However, this amendment was found inconsistent with other parts of the preexisting Food Code,

and it was withdrawn in 2002 during the transition between the two

codes, thereby continuing to allow absinthe manufacture and importation

through the existing permit-based system. These events were erroneously

reported by the media as it being reclassified from a prohibited product to a restricted product.

In 2007, the French Lucid brand

became the first genuine absinthe to receive a COLA (Certificate of

Label Approval) for importation into the United States since 1912, following independent efforts by representatives from Lucid and Kübler to overturn the long-standing US ban. In December 2007, St. George Absinthe Verte produced by St. George Spirits of Alameda, California became the first brand of American-made absinthe produced in the United States since the ban. Since that time, other micro-distilleries have started producing small batches in the US.

The 21st century has seen new types of absinthe, including various frozen preparations which have become increasingly popular.

The French Absinthe Ban of 1915 was repealed in May 2011 following

petitions by the Fédération Française des Spiritueux which represents

French distillers.

Production

Green anise, one of three main herbs used in production of absinthe

Grande wormwood, one of three main herbs used in production of absinthe

Sweet fennel, one of three main herbs used in production of absinthe

Most countries have no legal definition for absinthe, whereas the method of production and content of spirits such as whisky, brandy, and gin

are globally defined and regulated. Therefore, producers are at liberty

to label a product as "absinthe" or "absinth" without regard to any

specific legal definition or quality standards.

Producers of legitimate absinthes employ one of two historically

defined processes to create the finished spirit: distillation, or cold

mixing. In the sole country (Switzerland) that does possess a legal

definition of absinthe, distillation is the only permitted method of

production.

Distilled absinthe

Distilled

absinthe employs a method of production similar to that of high quality

gin. Botanicals are initially macerated in distilled base alcohol

before being redistilled to exclude bitter principles, and impart the

desired complexity and texture to the spirit.

Absinthe distillation, ca. 1904

The distillation of absinthe first yields a colourless distillate that leaves the alembic at around 72% ABV. The distillate may be reduced and bottled clear, to produce a Blanche or la Bleue absinthe, or it may be coloured to create a verte using natural or artificial colouring.

Traditional absinthes obtain their green colour strictly from the chlorophyll of whole herbs, which is extracted from the plants during the secondary maceration. This step involves steeping plants such as petite wormwood, hyssop, and melissa

(among other herbs) in the distillate. Chlorophyll from these herbs is

extracted in the process, giving the drink its famous green colour.

This step also provides a herbal complexity that is typical of

high quality absinthe. The natural colouring process is considered

critical for absinthe ageing, since the chlorophyll remains chemically

active. The chlorophyll serves a similar role in absinthe that tannins

do in wine or brown liquors.

After the colouring process, the resulting product is diluted

with water to the desired percentage of alcohol. The flavour of absinthe

is said to improve materially with storage, and many pre-ban

distilleries aged their absinthe in settling tanks before bottling.

Cold mixed absinthe

Many

modern absinthes are produced using a cold mix process. This

inexpensive method of production does not involve distillation, and is

regarded as inferior in the same way that cheaper compound gin is regarded as inferior to distilled

gin. The cold mixing process involves the simple blending of

flavouring essences and artificial colouring in commercial alcohol, in

similar fashion to most flavoured vodkas

and inexpensive liqueurs and cordials. Some modern cold mixed absinthes

have been bottled at strengths approaching 90% ABV. Others are

presented simply as a bottle of plain alcohol with a small amount of

powdered herbs suspended within it.

The lack of a formal legal definition for absinthe in most

countries enables some cold mixing producers to falsify advertising

claims, such as referring to their products as "distilled", since the

base alcohol itself was created at some point through distillation. This

is used as justification to sell these inexpensively produced absinthes

at prices comparable to more authentic absinthes that are distilled

directly from whole herbs. In the only country that possesses a formal

legal definition of absinthe (Switzerland), anything made via the cold

mixed process cannot be sold as absinthe.

Ingredients

Anise seeds

Absinthe is traditionally prepared from a distillation of neutral

alcohol, various herbs, spices and water. Traditional absinthes were

redistilled from a white grape spirit (or eau de vie), while lesser absinthes were more commonly made from alcohol from grain, beets, or potatoes. The principal botanicals are grande wormwood, green anise, and florence fennel, which are often called "the holy trinity." Many other herbs may be used as well, such as petite wormwood (Artemisia pontica or Roman wormwood), hyssop, melissa, star anise, angelica, peppermint, coriander, and veronica.

One early recipe was included in 1864's The English and Australian Cookery Book.

It directed the maker to "Take of the tops of wormwood, four pounds;

root of angelica, calamus aromaticus, aniseed, leaves of dittany, of

each one ounce; alcohol, four gallons. Macerate these substances during

eight days, add a little water, and distil by a gentle fire, until two

gallons are obtained. This is reduced to a proof spirit, and a few drops

of the oil of aniseed added."

Alternative colouring

Adding

to absinthe's negative reputation in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries, unscrupulous makers of the drink omitted the traditional

colouring phase of production in favour of adding toxic copper salts to

artificially induce a green tint. This practice may be responsible for

some of the alleged toxicity historically associated with this beverage.

Many modern day producers resort to similar (but non-deadly) shortcuts,

including the use of artificial food colouring to create the green

colour. Additionally, at least some cheap absinthes produced before the

ban were reportedly adulterated with poisonous antimony trichloride, reputed to enhance the louching effect.

Absinthe may also be naturally coloured pink or red using rose or hibiscus flowers. This was referred to as a rose (pink) or rouge (red) absinthe. Only one historical brand of rose absinthe has been documented.

Bottled strength

Absinthe was historically bottled at 45-74% percent ABV. Some modern Franco–Suisse absinthes are bottled at up to 83.2% ABV, while some modern, cold-mixed bohemian-style absinthes are bottled at up to 89.9% ABV.

Kits

The modern

day interest in absinthe has spawned a rash of absinthe kits from

companies that claim they produce homemade absinthe. Kits often call for

soaking herbs in vodka or alcohol, or adding a liquid concentrate to vodka or alcohol to create an ersatz

absinthe. Such practices usually yield a harsh substance that bears

little resemblance to the genuine article, and are considered

inauthentic by any practical standard.

Some concoctions may even be dangerous, especially if they call for

supplementation with potentially poisonous herbs, oils and/or extracts.

In at least one documented case, a person suffered acute kidney injury after drinking 10 ml of pure wormwood oil—a dose much higher than that found in absinthe.

Alternatives

In baking, Pernod Anise is often used as a substitute if absinthe is unavailable. In preparing the classic New Orleans-style Sazerac cocktail, various substitutes such as Pastis, Pernod, Ricard, and Herbsaint have been used to replace absinthe.

Preparation

Preparing absinthe using the traditional method, which does not involve burning.

Absinthe

spoons are designed to perch a sugar cube atop the glass, over which

ice-cold water is dripped to dilute the absinthe. The lip near the

centre of the handle lets the spoon rest securely on the rim of the

glass.

The traditional French preparation involves placing a sugar cube on top of a specially designed slotted spoon,

and placing the spoon on a glass filled with a measure of absinthe.

Iced water is poured or dripped over the sugar cube to mix the water

into the absinthe. The final preparation contains 1 part absinthe and

3-5 parts water. As water dilutes the spirit, those components with poor

water solubility (mainly those from anise, fennel, and star anise) come out of solution and cloud the drink. The resulting milky opalescence is called the louche (Fr. opaque or shady,

IPA [luʃ]). The release of these dissolved essences coincides with a

perfuming of herbal aromas and flavours that "blossom" or "bloom," and

brings out subtleties that are otherwise muted within the neat spirit.

This reflects what is perhaps the oldest and purest method of

preparation, and is often referred to as the French Method.

The Bohemian Method is a recent invention that involves fire, and was not performed during absinthe's peak of popularity in the Belle Époque.

Like the French method, a sugar cube is placed on a slotted spoon over a

glass containing one shot of absinthe. The sugar is pre-soaked in

alcohol (usually more absinthe), then set ablaze. The flaming sugar cube

is then dropped into the glass, thus igniting the absinthe. Finally, a

shot glass of water is added to douse the flames. This method tends to

produce a stronger drink than the French method. A variant of the

Bohemian Method involves allowing the fire to extinguish on its own.

This variant is sometimes referred to as "Cooking the Absinthe" or "The

Flaming Green Fairy." The origin of this burning ritual may borrow from a

coffee and brandy drink that was served at Café Brûlot, in which a

sugar cube soaked in brandy was set aflame.

Most experienced absintheurs do not recommend the Bohemian Method and

consider it a modern gimmick, as it can destroy the absinthe flavour and

present a fire hazard due to the unusually high alcohol content present

in absinthe.

Slowly dripping ice water from an absinthe fountain

Burning the sugar

In 19th century Parisian cafés, upon receiving an order for an

absinthe, a waiter would present the patron with a dose of absinthe in a

suitable glass, sugar, absinthe spoon, and a carafe of iced water.

It was up to the patron to prepare the drink, as the inclusion or

omission of sugar was strictly an individual preference, as was the

amount of water used. As the popularity of the drink increased,

additional accoutrements of preparation appeared, including the absinthe fountain, which was effectively a large jar of iced water with spigots,

mounted on a lamp base. This let drinkers prepare a number of drinks at

once—and with a hands-free drip, patrons could socialise while louching

a glass.

Although many bars served absinthe in standard glassware, a

number of glasses were specifically designed for the French absinthe

preparation ritual. Absinthe glasses were typically fashioned with a

dose line, bulge, or bubble in the lower portion denoting how much

absinthe should be poured. One "dose" of absinthe ranged anywhere around

2-2.5 fluid ounces (60-75 ml).

In addition to being prepared with sugar and water, absinthe emerged as a

popular cocktail ingredient in both the United Kingdom and the United

States. By 1930, dozens of fancy cocktails that called for absinthe had

been published in numerous credible bartender guides. One of the most famous of these libations is Ernest Hemingway's "Death in the Afternoon"

cocktail, a tongue-in-cheek concoction that contributed to a 1935

collection of celebrity recipes. The directions are as follows: "Pour

one jigger

absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains

the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink three to five of these slowly."

Styles

The Absinthe Drinker by Viktor Oliva (1861–1928)

The Drinkers by Jean Béraud (1908)

Most categorical alcoholic beverages have regulations governing their

classification and labelling, while those governing absinthe have

always been conspicuously lacking. According to popular treatises from

the 19th century, absinthe could be loosely categorised into several

grades (ordinaire, demi-fine, fine, and Suisse—the

latter does not denote origin), in order of increasing alcoholic

strength and quality. Many contemporary absinthe critics simply classify

absinthe as distilled or mixed, according to its

production method. And while the former is generally considered far

superior in quality to the latter, an absinthe's simple claim of being

'distilled' makes no guarantee as to the quality of its base ingredients

or the skill of its maker.

- Blanche absinthe ("white" in French, also referred to as la Bleue in Switzerland) is bottled directly following distillation and reduction, and is uncoloured (clear). The name la Bleue was originally a term used for Swiss bootleg absinthe (which was bottled colourless so as to be visually indistinct from other spirits during the era of absinthe prohibition), but has become a popular term for post-ban Swiss-style absinthe in general. Blanches are often lower in alcohol content than vertes, though this is not necessarily so; the only truly differentiating factor is that blanches are not put through a secondary maceration stage, and thus remain colourless like other distilled liquors.

- Verte absinthe ("green" in French, sometimes called la Fée Verte) begins as a blanche. The blanche is altered by a secondary maceration stage, in which a separate mixture of herbs is steeped into the clear distillate. This confers a peridot green hue and an intense flavour. Vertes represent the prevailing type of absinthe that was found in the 19th century. Vertes are typically more alcoholic than blanches, as the high amounts of botanical oils conferred during the secondary maceration only remain miscible at lower concentrations of water, thus vertes are usually bottled at closer to still-strength. Artificially coloured green absinthes may also be claimed to be verte, though they lack the characteristic herbal flavours that result from maceration in whole herbs.

- Absenta ("absinthe" in Spanish) is sometimes associated with a regional style that often differed slightly from its French cousin. Traditional absentas may taste slightly different due to their use of Alicante anise, and often exhibit a characteristic citrus flavour.

- Hausgemacht (German for home-made, often abbreviated as HG) refers to clandestine absinthe (not be confused with the Swiss La Clandestine brand) that is home-distilled by hobbyists. It should not be confused with absinthe kits. Hausgemacht absinthe is produced in tiny quantities for personal use and not for the commercial market. Clandestine production increased after absinthe was banned, when small producers went underground, most notably in Switzerland. Although the ban has been lifted in Switzerland, some clandestine distillers have not legitimised their production. Authorities believe that high taxes on alcohol and the mystique of being underground are likely reasons.

- Bohemian-style absinth is also referred to as Czech-style absinthe, anise-free absinthe, or just "absinth" (without the "e"), and is best described as a wormwood bitters. It is produced mainly in Czechia, from which it gets its designation as Bohemian or Czech, although not all absinthes from Czechia are Bohemian-style. Bohemian-style absinth typically contains little or none of the anise, fennel, and other herbal flavours associated with traditional absinthe, and thus bears very little resemblance to the absinthes made popular in the 19th century. Typical Bohemian-style absinth has only two similarities with its authentic, traditional counterpart: it contains wormwood and has a high alcohol content. The Czechs are credited with inventing the fire ritual in the 1990s, possibly because Bohemian-style absinth does not louche, which renders the traditional French preparation method useless. As such, this type of absinthe and the fire ritual associated with it are entirely modern fabrications, and have little to no relationship with the historical absinthe tradition.

Storage

Absinthe

that is artificially coloured or clear is aesthetically stable, and can

be bottled in clear glass. If naturally coloured absinthe is exposed to

light or air for a prolonged period, the chlorophyll

gradually becomes oxidised, which has the effect of gradually changing

the colour from green to yellow green, and eventually to brown. The

colour of absinthe that has completed this transition was historically

referred to as feuille morte ("dead leaf"). In the pre-ban era,

this natural phenomenon was favourably viewed, for it confirmed the

product in question was coloured naturally, and not artificially with

potentially toxic chemicals. Predictably, vintage absinthes often emerge

from sealed bottles as distinctly amber in tint due to decades of slow

oxidation. Though this colour change presents no adverse impact to the

flavour of absinthe, it is generally desired to preserve the original

colour, which requires that naturally coloured absinthe be bottled in

dark, light resistant bottles. Absinthe intended for decades of storage

should be kept in a cool (room temperature), dry place, away from light and heat. Absinthe should not be stored in the refrigerator or freezer, as the anethole may polymerise inside the bottle, creating an irreversible precipitate, and adversely impacting the original flavour.

Health effects

Absinthe has been frequently and improperly described in modern times as being hallucinogenic. No peer-reviewed scientific study has demonstrated absinthe to possess hallucinogenic properties.

The belief that absinthe induces hallucinogenic effects is at least

partly rooted in the fact that following some ten years of experiments

with wormwood oil in the 19th century, the French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan

studied 250 cases of alcoholism, and claimed that those who drank

absinthe were worse off than those drinking ordinary alcohol, having

experienced rapid-onset hallucinations. Such accounts by opponents of absinthe (like Magnan) were cheerfully embraced by famous absinthe drinkers, many of whom were bohemian artists or writers.

Two famous artists who helped popularise the notion that absinthe had powerful psychoactive properties were Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh.

In one of the best-known written accounts of absinthe drinking, an

inebriated Oscar Wilde described a phantom sensation of having tulips

brush against his legs after leaving a bar at closing time.

Notions of absinthe's alleged hallucinogenic properties were

again fuelled in the 1970s, when a scientific paper suggested that

thujone's structural similarity to THC, the active chemical in cannabis, presented the possibility of THC receptor affinity. This theory was conclusively disproven in 1999.

The debate over whether absinthe produces effects on the human

mind in addition to those of alcohol has not been conclusively resolved.

The effects of absinthe have been described by some as mind opening.

The most commonly reported experience is a "clear-headed" feeling of

inebriation—a form of "lucid drunkenness". Chemist, historian and

absinthe distiller Ted Breaux has claimed that the alleged secondary

effects of absinthe may be caused by the fact that some of the herbal

compounds in the drink act as stimulants, while others act as sedatives, creating an overall lucid effect of awakening.

The long-term effects of moderate absinthe consumption in humans remain

unknown, although herbs traditionally used in the production of

absinthe are reported to have both painkilling and antiparasitic properties.

Today it is known that absinthe does not cause hallucinations.

It is widely accepted that reports of hallucinogenic effects of

absinthe were attributable to the poisonous adulterants being added to

cheaper versions of the drink in the 19th century, such as oil of wormwood, impure alcohol, and poisonous colouring matter (e.g. copper salts).

Controversy

It

was once widely promoted that excessive absinthe drinking caused

effects that were discernible from those associated with alcoholism, a

belief that led to the coining of the term absinthism. One of the first vilifications of absinthe followed an 1864 experiment in which Magnan simultaneously exposed one guinea pig

to large doses of pure wormwood vapour, and another to alcohol vapours.

The guinea pig exposed to wormwood vapour experienced convulsive

seizures, while the animal exposed to alcohol did not. Magnan would

later blame the naturally occurring (in wormwood) chemical thujone for these effects.

Thujone, once widely believed to be an active chemical in absinthe, is a GABA

antagonist, and while it can produce muscle spasms in large doses,

there is no direct evidence to suggest it causes hallucinations. Past reports estimated thujone concentrations in absinthe as being up to 260 mg/kg.

More recently, published scientific analyses of samples of various

original absinthes have disproved previous estimates, and demonstrated

that only a trace of the thujone present in wormwood actually makes it

into a properly distilled absinthe when historical methods and materials

are employed to create the spirit. As such, most traditionally crafted

absinthes, both vintage and modern, fall within the current EU

standards.

Tests conducted on mice to study toxicity showed an oral LD50 of about 45 mg thujone per kg of body weight,

which represents far more absinthe than could be realistically

consumed. The high percentage of alcohol in absinthe would result in

mortality long before thujone could become a factor. In documented cases of acute thujone poisoning as a result of oral ingestion, the source of thujone was not commercial absinthe, but rather non-absinthe-related sources, such as common essential oils (which may contain as much as 50% thujone).

One study published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol concluded that high doses (0.28 mg/kg) of thujone in alcohol had

negative effects on attention performance in a clinical setting. It

delayed reaction time,

and caused subjects to concentrate their attention into the central

field of vision. Low doses (0.028 mg/kg) did not produce an effect

noticeably different from the plain alcohol control. While the effects

of the high dose samples were statistically significant in a double blind

test, the test subjects themselves were unable to reliably identify

which samples contained thujone. For the average 65 kg (143 lb) man, the

high dose samples in the study would equate to 18.2 mg of thujone. The

EU limit of 35 mg/L of thujone in absinthe means that given the highest

permitted thujone content, that individual would need to consume

approximately 0.5 litres of high proof (e.g. 50%+ ABV) spirit before the

thujone could be metabolized in order to display effects detectable in a

clinical setting, which would result in a potentially lethal BAC more than 0.4%.

Regulations

Most countries (except Switzerland) at present do not possess a legal definition of absinthe (unlike Scotch whisky or cognac).

Accordingly, producers are free to label a product "absinthe" or

"absinth", whether or not it bears any resemblance to the traditional

spirit.

Australia

Absinthe is readily available in many bottle shops. Bitters may contain a maximum 35 mg/kg thujone, while other alcoholic beverages can contain a maximum 10 mg/kg. The domestic production and sale of absinthe is regulated by state licensing laws.

Until July 13, 2013, the import and sale of absinthe technically

required a special permit, since "oil of wormwood, being an essential

oil obtained from plants of the genus Artemisia, and preparations containing oil of wormwood" were listed as item 12A, Schedule 8, Regulation 5H of the Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations 1956 (Cth). These controls have now been repealed, and permission is no longer required.

Brazil

Absinthe

was prohibited in Brazil until 1999 and was brought by entrepreneur

Lalo Zanini and legalised in the same year. Presently, absinthe sold in

Brazil must abide by the national law that restricts all spirits to a

maximum of 54.0% ABV. While this regulation is enforced throughout

channels of legal distribution, it may be possible to find absinthe

containing alcohol in excess of the legal limit in some restaurants or

food fairs.

Canada

In Canada, liquor laws concerning the production, distribution, and sale of spirits are written and enforced by individual provincial

government monopolies. Each product is subject to the approval of a

respective individual provincial liquor board before it can be sold in

that province. Importation is a federal matter, and is enforced by the Canada Border Services Agency.

The importation of a nominal amount of liquor by individuals for

personal use is permitted, provided that conditions for the individual's

duration of stay outside the country are satisfied.

- British Columbia, New Brunswick: no established limits on thujone content

- Alberta, Ontario: 10 mg/kg

- Manitoba: 6–8 mg

- Quebec: 15 mg/kg

- Newfoundland and Labrador: absinthe sold in provincial liquor store outlets

- Nova Scotia: absinthe sold in provincial liquor store outlets

- Prince Edward Island: absinthe is not sold in provincial liquor store outlets, but one brand (Deep Roots) produced on the island can be procured locally.

- Saskatchewan: Only one brand listed in provincial liquor stores, although an individual is permitted to import one case (usually twelve 750 ml bottles or eight one-litre bottles) of any liquor.

In 2007, Canada's first genuine absinthe (Taboo Absinthe) was created by Okanagan Spirits Craft Distillery in British Columbia.

European Union

The European Union permits a maximum thujone level of 35 mg/kg in alcoholic beverages where Artemisia species is a listed ingredient, and 10 mg/kg in other alcoholic beverages. Member countries regulate absinthe production within this framework. The sale of absinthe is permitted in all EU countries unless they further regulate it.

Finland

The

sale and production of absinthe was prohibited in Finland from 1919 to

1932; no current prohibitions exist. The government-owned chain of

liquor stores (Alko)

is the only outlet that may sell alcoholic beverages containing over

5.5% ABV, although national law bans the sale of alcoholic beverages

containing over 60% ABV.

France

Despite

adopting sweeping EU food and beverage regulations in 1988 that

effectively re-legalised absinthe, a decree was passed that same year

that preserved the prohibition on products explicitly labelled as

"absinthe", while placing strict limits on fenchone (fennel) and

pinocamphone (hyssop)

in an obvious, but failed, attempt to thwart a possible return of

absinthe-like products. French producers circumvented this regulatory

obstacle by labelling absinthe as spiritueux à base de plantes d'absinthe

('wormwood-based spirits'), with many either reducing or omitting

fennel and hyssop altogether from their products. A legal challenge to

the scientific basis of this decree resulted in its repeal (2009),

which opened the door for the official French re-legalisation of

absinthe for the first time since 1915. The French Senate voted to

repeal the prohibition in mid-April 2011.

Georgia

It is legal to produce and sell absinthe in Georgia, which has claimed to possess several producers of absinthe.

Germany

A ban

on absinthe was enacted in Germany on 27 March 1923. In addition to

banning the production of and commercial trade in absinthe, the law went

so far as to prohibit the distribution of printed matter that provided

details of its production. The original ban was lifted in 1981, but the

use of Artemisia absinthium as a flavouring agent remained

prohibited. On 27 September 1991, Germany adopted the European Union's

standards of 1988, which effectively re-legalised absinthe.

Italy

The Fascist regime in 1926 banned the production, import, transport and sale of any liquor named "Assenzio".

The ban was reinforced in 1931 with harsher penalties for

transgressors, and remained in force until 1992 when the Italian

government amended its laws to comply with the EU directive 88/388/EEC.

New Zealand

Although absinthe is not prohibited at national level, some local authorities have banned it. The latest is Mataura in Southland.

The ban came in August 2008 after several issues of misuse drew public

and police attention. One incident resulted in breathing difficulties

and hospitalisation of a 17-year-old for alcohol poisoning. The particular brand of absinthe that caused these effects was bottled at an unusually high 89.9% ABV.

Sweden and Norway

The

sale and production of absinthe has never been prohibited in Sweden or

Norway. However, the only outlet that may sell alcoholic beverages

containing more than 3.5% ABV in Sweden and 4.75% ABV in Norway, is the

government-owned chain of liquor stores known as Systembolaget in Sweden and Vinmonopolet in Norway. Systembolaget and Vinmonopolet did not import or sell absinthe for many years after the ban in France;

however, today several absinthes are available for purchase in

Systembolaget stores, including Swedish made distilled absinthe. In

Norway, on the other hand, one is less likely to find many absinthes

since Norwegian alcohol law prohibits the sale and importation of

alcoholic beverages above 60% abv, which eliminates most absinthes.

Switzerland

La fin de la Fée Verte (The End of the Green Fairy): Swiss poster criticising the country's prohibition of absinthe in 1910

In Switzerland, the sale and production of absinthe was prohibited from 1910 to March 1, 2005. This was based on a vote in 1908. To be legally made or sold in Switzerland, absinthe must be distilled, must not contain certain additives, and must be either naturally coloured or left uncoloured.

In 2014, the Federal Administrative Court of Switzerland invalidated a governmental decision of 2010 which allowed only absinthe made in the Val-de-Travers

region to be labeled as absinthe in Switzerland. The court found that

absinthe was a label for a product and was not tied to a geographic

origin.

United States

In 2007, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

(TTB) effectively lifted the long-standing absinthe ban, and it has

since approved many brands for sale in the US market. This was made

possible partly through the TTB's clarification of the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) thujone content regulations, which specify that finished food and beverages that contain Artemisia species must be thujone-free. In this context, the TTB considers a product thujone-free if the thujone content is less than 10 ppm (equal to 10 mg/kg). This is verified through the use of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The brands Kübler and Lucid and their lawyers did most of the work to get absinthe legalized in the U.S., over the 2004-2007 time period.

In the U.S., March 5 sometimes is referred to as "National Absinthe

Day" as it was the day the 95-year ban on absinthe was finally lifted.

The import, distribution, and sale of absinthe is permitted subject to the following restrictions:

- The product must be thujone-free as per TTB guidelines,

- The word "absinthe" can neither be the brand name nor stand alone on the label, and

- The packaging cannot "project images of hallucinogenic, psychotropic, or mind-altering effects."

Absinthe imported in violation of these regulations is subject to seizure at the discretion of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Beginning in 2000, a product called Absente

was sold legally in the United States under the marketing tagline

"Absinthe Refined," but as the product contained sugar, and was made

with southernwood (Artemisia abrotanum) and not grande wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) (prior to 2009), the TTB classified it as a liqueur.

Pablo Picasso, 1901-02, Femme au café (Absinthe Drinker), oil on canvas, 73 cm × 54 cm (29 in × 21 in), Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Vanuatu

The Absinthe (Prohibition) Act 1915, passed in the New Hebrides, has never been repealed, is included in the 2006 Vanuatu

consolidated legislation, and contains the following all-encompassing

restriction: "The manufacture, importation, circulation and sale

wholesale or by retail of absinthe or similar liquors in Vanuatu shall

be prohibited."

Cultural influence

Numerous artists and writers living in France in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries were noted absinthe drinkers, and featured absinthe

in their work. Some of these included Édouard Manet, Guy de Maupassant, Amedeo Modigliani, Arthur Rimbaud, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Verlaine, Vincent van Gogh, Oscar Wilde, and Émile Zola. Many other renowned artists and writers similarly drew from this cultural well, including Aleister Crowley, Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, August Strindberg and Erik Satie.

The aura of illicitness and mystery surrounding absinthe has

played into literature, movies, music, and television, where it is often

portrayed as a mysterious, addictive, and mind-altering drink. Absinthe

has served as the subject of numerous works of fine art, films, video,

music, and literature since the mid-19th-century. Some of the earliest

film references include The Hasher's Delirium (1910) by Émile Cohl, an early pioneer in the art of animation, as well as two different silent films, each entitled Absinthe, from 1913 and 1914 respectively.

On November 9, 2018, the alternative rock band I Don't Know How But They Found Me released a song titled "Absinthe" as part of their 1981 Extended Play.