The study of Internet linguistics can take place through four main perspectives: sociolinguistics, education, stylistics and applied linguistics. Further dimensions have developed as a result of further technological advances - which include the development of the Web as corpus and the spread and influence of the stylistic variations brought forth by the spread of the Internet, through the mass media and through literary works.

In view of the increasing number of users connected to the Internet,

the linguistics future of the Internet remains to be determined, as new

computer-mediated technologies continue to emerge and people adapt their

languages to suit these new media.

The Internet continues to play a significant role both in encouraging

as well as in diverting attention away from the usage of languages.

Main perspectives

David

Crystal has identified four main perspectives for further investigation

– the sociolinguistic perspective, the educational perspective, the

stylistic perspective and the applied perspective. The four perspectives are effectively interlinked and affect one another.

Sociolinguistic perspective

This perspective deals with how society views the impact of Internet development on languages.

The advent of the Internet has revolutionized communication in many

ways; it changed the way people communicate and created new platforms

with far-reaching social impact. Significant avenues include but are not

limited to SMS text messaging, e-mails, chatgroups, virtual worlds and the Web.

The evolution of these new mediums of communications has raised

much concern with regards to the way language is being used. According

to Crystal (2005), these concerns are neither without grounds nor unseen

in history – it surfaces almost always when a new technology

breakthrough influences languages; as seen in the 15th century when printing was introduced, the 19th century when the telephone was invented and the 20th century when broadcasting began to penetrate our society.

At a personal level, CMC such as SMS Text Messaging and mobile e-mailing (push mail) has greatly enhanced instantaneous communication. Some examples include the iPhone and the BlackBerry.

In schools, it is not uncommon for educators and students to be

given personalized school e-mail accounts for communication and

interaction purposes. Classroom discussions are increasingly being

brought onto the Internet in the form of discussion forums. For

instance, at Nanyang Technological University,

students engage in collaborative learning at the university’s portal –

edveNTUre, where they participate in discussions on forums and online

quizzes and view streaming podcasts prepared by their course instructors

among others. iTunes U in 2008 began to collaborate with universities as they converted the Apple

music service into a store that makes available academic lectures and

scholastic materials for free – they have partnered more than 600

institutions in 18 countries including Oxford, Cambridge and Yale Universities.

These forms of academic social networking and media are slated to

rise as educators from all over the world continue to seek new ways to

better engage students. It is commonplace for students in New York University to interact with “guest speakers weighing in via Skype, library staffs providing support via instant messaging, and students accessing library resources from off campus.” This will affect the way language is used as students and teachers begin to use more of these CMC platforms.

At a professional level, it is a common sight for companies to

have their computers and laptops hooked up onto the Internet (via wired

and wireless Internet connection),

and for employees to have individual e-mail accounts. This greatly

facilitates internal (among staffs of the company) and external (with

other parties outside of one’s organization) communication. Mobile

communications such as smart phones

are increasingly making their way into the corporate world. For

instance, in 2008, Apple announced their intention to actively step up

their efforts to help companies incorporate the iPhone into their

enterprise environment, facilitated by technological developments in

streamlining integrated features (push e-mail, calendar and contact

management) using ActiveSync.

In general, these new CMCs that are made possible by the Internet

have altered the way people use language – there is heightened

informality and consequently a growing fear of its deterioration.

However, as David Crystal puts it, these should be seen positively as it

reflects the power of the creativity of a language.

Themes

The sociolinguistics of the Internet may also be examined through five interconnected themes.

- Multilingualism – It looks at the prevalence and status of various languages on the Internet.

- Language change – From a sociolinguistic perspective, language change is influenced by the physical constraints of technology (e.g. typed text) and the shifting social-economic priorities such as globalization. It explores the linguistic changes over time, with emphasis on Internet lingo.

- Conversation discourse – It explores the changes in patterns of social interaction and communicative practice on the Internet.

- Stylistic diffusion – It involves the study of the spread of Internet jargons and related linguistic forms into common usage. As language changes, conversation discourse and stylistic diffusion overlap with the aspect of language stylistics.

- Metalanguage and folk linguistics – It involves looking at the way these linguistic forms and changes on the Internet are labelled and discussed (e.g. impact of Internet lingo resulted in the 'death' of the apostrophe and loss of capitalization.)

Educational perspective

The educational perspective of internet linguistics examines the Internet's impact on formal language use, specifically on Standard English, which in turn affects language education.

The rise and rapid spread of Internet use has brought about new

linguistic features specific only to the Internet platform. These

include, but are not limited to, an increase in the use of informal

written language, inconsistency in written styles and stylistics

and the use of new abbreviations in Internet chats and SMS text

messaging, where constraints of technology on word count contributed to

the rise of new abbreviations. Such acronyms

exist primarily for practical reasons — to reduce the time and effort

required to communicate through these mediums apart from technological

limitations. Examples of common acronyms include lol (for laughing out loud; a general expression of laughter), omg (oh my god) and gtg (got to go).

The educational perspective has been considerably established in

the research on the Internet's impact on language education. It is an

important and crucial aspect as it affects and involves the education of

current and future student generations in the appropriate and timely

use of informal language that arises from Internet usage.

There are concerns for the growing infiltration of informal language

use and incorrect word use into academic or formal situations, such as

the usage of casual words like "guy" or the choice of the word

"preclude" in place of "precede" in academic papers by students. There

are also issues with spellings and grammar occurring at a higher

frequency among students' academic works as noted by educators, with the

use of abbreviations such as "u" for "you" and "2" for "to" being the

most common.

Linguists and professors like Eleanor Johnson suspect that

widespread mistakes in writing are strongly connected to Internet usage,

where educators have similarly reported new kinds of spelling and

grammar mistakes in student works. There is, however, no scientific evidence to confirm the proposed connection.

Though there are valid concerns about Internet usage and its impact on

students' academic and formal writing, its severity is however enlarged

by the informal nature of the new media platforms. Naomi S. Baron (2008) argues in Always On

that student writings suffer little impact from the use of

Internet-mediated communication (IMC) such as internet chat, SMS text

messaging and e-mail. A study in 2009 published by the British Journal of Developmental Psychology

found that students who regularly texted (sent messages via SMS using a

mobile phone) displayed a wider range of vocabulary and this may lead

to a positive impact on their reading development.

Though the use of the Internet resulted in stylistics that are

not deemed appropriate in academic and formal language use, it is to be

noted that Internet use may not hinder language education but instead

aid it. The Internet has proven in different ways that it can provide

potential benefits in enhancing language learning, especially in second

or foreign language learning.

Language education through the Internet in relation to Internet

linguistics is, most significantly, applied through the communication

aspect (use of e-mails, discussion forums, chat messengers, blogs, etc.).

IMC allows for greater interaction between language learners and native

speakers of the language, providing for greater error corrections and

better learning opportunities of standard language, in the process

allowing the picking up of specific skills such as negotiation and

persuasion.

Stylistic perspective

This

perspective examines how the Internet and its related technologies have

encouraged new and different forms of creativity in language,

especially in literature.

It looks at the Internet as a medium through which new language

phenomena have arisen. This new mode of language is interesting to study

because it is an amalgam of both spoken and written languages. For

example, traditional writing is static compared to the dynamic nature of

the new language on the Internet where words can appear in different

colors and font sizes on the computer screen.

Yet, this new mode of language also contains other elements not found

in natural languages. One example is the concept of framing found in

e-mails and discussion forums. In replying to e-mails, people generally

use the sender’s e-mail message as a frame to write their own messages.

They can choose to respond to certain parts of an e-mail message while

leaving other bits out. In discussion forums, one can start a new thread

and anyone regardless of their physical location can respond to the

idea or thought that was set down through the Internet. This is

something that is usually not found in written language.

Future research also includes new varieties of expressions that

the Internet and its various technologies are constantly producing and

their effects not only on written languages but also their spoken forms.

The communicative style of Internet language is best observed in the

CMC channels below, as there are often attempts to overcome

technological restraints such as transmission time lags and to

re-establish social cues that are often vague in written text.

Mobile phones

Mobile phones (also called cell phones) have an expressive potential

beyond their basic communicative functions. This can be seen in

text-messaging poetry competitions such as the one held by The Guardian.

The 160-character limit imposed by the cell phone has motivated users

to exercise their linguistic creativity to overcome them. A similar

example of new technology with character constraints is Twitter, which has a 280-character limit. There have been debates as to whether these new abbreviated forms introduced in users’ Tweets

are "lazy" or whether they are creative fragments of communication.

Despite the ongoing debate, there is no doubt that Twitter has

contributed to the linguistic landscape with new lingoes and also

brought about a new dimension of communication.

The cell phone has also created a new literary genre – cell phone novels.

A typical cell phone novel consists of several chapters which readers

download in short installments. These novels are in their "raw" form as

they do not go through editing processes like traditional novels. They

are written in short sentences, similar to text-messaging.

Authors of such novels are also able to receive feedback and new ideas

from their readers through e-mails or online feedback channels. Unlike

traditional novel writing, readers’ ideas sometimes get incorporated

into the storyline or authors may also decide to change their story’s

plot according to the demand and popularity of their novel (typically

gauged by the number of download hits).

Despite their popularity, there has also been criticism regarding the novels’ "lack of diverse vocabulary" and poor grammar.

Blogs

Blogging has brought about new ways of writing diaries and from a

linguistic perspective, the language used in blogs is "in its most

'naked' form",

published for the world to see without undergoing the formal editing

process. This is what makes blogs stand out because almost all other

forms of printed language have gone through some form of editing and

standardization. David Crystal stated that blogs were "the beginning of a new stage in the evolution of the written language". Blogs have become so popular that they have expanded beyond written blogs, with the emergence of photoblog, videoblog, audioblog and moblog.

These developments in interactive blogging have created new linguistic

conventions and styles, with more expected to arise in the future.

Virtual worlds

Virtual worlds provide insights into how users are adapting the usage

of natural language for communication within these new mediums. The

Internet language that has arisen through user interactions in

text-based chatrooms and computer-simulated worlds has led to the development of slangs within digital communities. Examples of these include pwn and noob. Emoticons

are further examples of how users have adapted different expressions to

suit the limitations of cyberspace communication, one of which is the

"loss of emotivity".

Communication in niches such as role-playing games (RPG) of Multi-User domains

(MUDs) and virtual worlds is highly interactive, with emphasis on

speed, brevity and spontaneity. As a result, CMC is generally more

vibrant, volatile, unstructured and open. There are often complex

organization of sequences and exchange structures evident in the

connection of conversational strands and short turns. Some of the CMC

strategies used include capitalization for words such as EMPHASIS, usage of symbols such as the asterisk to enclose words as seen in *stress* and the creative use of punctuation like ???!?!?!?. Symbols are also used for discourse functions, such as the asterisk as a conversational repair marker and arrows and carats as deixis and referent markers. Besides contributing to these new forms in language, virtual worlds are also being used to teach languages. Virtual world language learning

provides students with simulations of real-life environments, allowing

them to find creative ways to improve their language skills. Virtual

worlds are good tools for language learning among the younger learners

because they already see such places as a "natural place to learn and

play".

One of the most popular Internet-related technologies to be studied

under this perspective is e-mail, which has expanded the stylistics of

languages in many ways. A study done on the linguistic profile of

e-mails has shown that there is a hybrid of speech and writing styles in

terms of format, grammar and style. E-mail is rapidly replacing traditional letter-writing because of its convenience, speed and spontaneity.

It is often related to informality as it feels temporary and can be

deleted easily. However, as this medium of communication matures, e-mail

is no longer confined to sending informal messages between friends and

relatives. Instead, business correspondences are increasingly being

carried out through e-mails. Job seekers are also using e-mails to send

their resumes to potential employers. The result of a move towards more

formal usages will be a medium representing a range of formal and

informal stylistics.

While e-mail has been blamed for students’ increased usage of

informal language in their written work, David Crystal argues that

e-mail is "not a threat, for language education" because e-mail with its

array of stylistic expressiveness can act as a domain for language

learners to make their own linguistic choices responsibly. Furthermore,

the younger generation’s high propensity for using e-mail may improve

their writing and communication skills because of the efforts they are

making to formulate their thoughts and ideas, albeit through a digital

medium.

Instant messaging

Like other forms of online communication, instant messaging has also

developed its own acronyms and short forms. However, instant messaging

is quite different from e-mail and chatgroups because it allows

participants to interact with one another in real-time while conversing

in private.

With instant messaging, there is an added dimension of familiarity

among participants. This increased degree of intimacy allows greater

informality in language and "typographical idiosyncrasies". There are

also greater occurrences of stylistic variation because there can be a

very wide age gap between participants. For example, a granddaughter can

catch up with her grandmother through instant messaging. Unlike

chatgroups where participants come together with shared interests, there

is no pressure to conform in language here.

Applied perspective

The applied perspective views the linguistic exploitation of the

Internet in terms of its communicative capabilities – the good and the

bad.

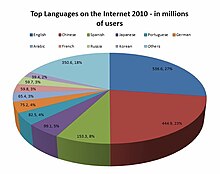

The Internet provides a platform where users can experience

multilingualism. Although English is still the dominant language used on

the Internet, other languages are gradually increasing in their number

of users. The Global Internet usage

page provides some information on the number of users of the Internet

by language, nationality and geography. This multilingual environment

continues to increase in diversity as more language communities become

connected to the Internet. The Internet is thus a platform where

minority and endangered languages

can seek to revive their language use and/or create awareness. This can

be seen in two instances where it provides these languages

opportunities for progress in two important regards - language documentation and language revitalization.

Language documentation

Firstly, the Internet facilitates language documentation. Digital

archives of media such as audio and video recordings not only help to

preserve language documentation, but also allows for global

dissemination through the Internet.

Publicity about endangered languages, such as Webster (2003) has helped

to spur a worldwide interest in linguistic documentation.

Foundations such as the Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project

(HRELP), funded by Arcadia also help to develop the interest in

linguistic documentation. The HRELP is a project that seeks to document

endangered languages, preserve and disseminate documentation materials

among others. The materials gathered are made available online under its

Endangered Languages Archive (ELAR) program.

Other online materials that support language documentation

include the Language Archive Newsletter which provides news and articles

about topics in endangered languages. The web version of Ethnologue

also provides brief information of all of the world’s known living

languages. By making resources and information of endangered languages

and language documentation available on the Internet, it allows

researchers to build on these materials and hence preserve endangered

languages.

Language revitalization

Secondly, the Internet facilitates language revitalization.

Throughout the years, the digital environment has developed in various

sophisticated ways that allow for virtual contact. From e-mails, chats

to instant messaging, these virtual environments have helped to bridge

the spatial distance between communicators. The use of e-mails has been

adopted in language courses to encourage students to communicate in

various styles such as conference-type formats and also to generate

discussions.

Similarly, the use of e-mails facilitates language revitalization in

the sense that speakers of a minority language who moved to a location

where their native language is not being spoken can take advantage of

the Internet to communicate with their family and friends, thus

maintaining the use of their native language. With the development and

increasing use of telephone broadband communication such as Skype, language revitalization through the internet is no longer restricted to literate users.

Hawaiian educators have been taking advantage of the Internet in their language revitalization programs.

The graphical bulletin board system, Leoki (Powerful Voice), was

established in 1994. The content, interface and menus of the system are

entirely in the Hawaiian language. It is installed throughout the

immersion school system and includes components for e-mails, chat,

dictionary and online newspaper among others. In higher institutions

such as colleges and universities where the Leoki system is not yet

installed, the educators make use of other software and Internet tools

such as Daedalus Interchange, e-mails and the Web to connect students of

Hawaiian language with the broader community.

Another use of the Internet includes having students of minority

languages write about their native cultures in their native languages

for distant audiences. Also, in an attempt to preserve their language

and culture, Occitan

speakers have been taking advantage of the Internet to reach out to

other Occitan speakers from around the world. These methods provide

reasons for using the minority languages by communicating in it.

In addition, the use of digital technologies, which the young

generation think of as ‘cool’, will appeal to them and in turn maintain

their interest and usage of their native languages.

Exploitation of the Internet

The Internet can also be exploited for activities such as terrorism, internet fraud and pedophilia. In recent years, there has been an increase in crimes that involved the use of the Internet such as e-mails and Internet Relay Chat (IRC), as it is relatively easy to remain anonymous.

These conspiracies carry concerns for security and protection. From a

forensic linguistic point of view, there are many potential areas to

explore. While developing a chat room child protection procedure

based on search terms filtering is effective, there is still minimal

linguistically orientated literature to facilitate the task. In other areas, it is observed that the Semantic Web has been involved in tasks such as personal data protection, which helps to prevent fraud.

Dimensions

The

dimensions covered in this section include looking at the Web as a

corpus and issues of language identification and normalization. The

impacts of internet linguistics on everyday life are examined under the

spread and influence of Internet stylistics, trends of language change

on the Internet and conversation discourse.

The Web as a corpus

With

the Web being a huge reservoir of data and resources, language

scientists and technologists are increasingly turning to the web for

language data. Corpora were first formally mentioned in the field of computational linguistics

at the 1989 ACL meeting in Vancouver. It was met with much controversy

as they lacked theoretical integrity leading to much skepticism of their

role in the field, until the publication of the journal ‘Using Large Corpora’ in 1993 that the relationship between computational linguistics and corpora became widely accepted.

To establish whether the Web is a corpus, it is worthwhile to

turn to the definition established by McEnery and Wilson (1996, pp 21).

In principle, any collection of more than one text can be called a corpus. . . . But the term “corpus” when used in the context of modern linguistics tends most frequently to have more specific connotations than this simple definition provides for. These may be considered under four main headings: sampling and representativeness, finite size, machine-readable form, a standard reference.

— Tony McEnery and Andrew Wilson, Corpus Linguistics

Relating closer to the Web as a Corpus, Manning and Schütze (1999, pp 120) further streamlines the definition:

In Statistical NLP [Natural Language Processing], one commonly receives as a corpus a certain amount of data from a certain domain of interest, without having any say in how it is constructed. In such cases, having more training data is normally more useful than any concerns of balance, and one should simply use all the text that is available.

— Christopher Manning and Hinrich Schütze, Foundations of Statistical Language Processing

Hit counts were used for carefully constructed search engine queries

to identify rank orders for word sense frequencies, as an input to a

word sense disambiguation engine.

This method was further explored with the introduction of the concept

of a parallel corpora where the existing Web pages that exist in

parallel in local and major languages be brought together. It was demonstrated that it is possible to build a language-specific corpus from a single document in that specific language.

Themes

There

has been much discussion about the possible developments in the arena of

the Web as a corpus. The development of using the web as a data source

for word sense disambiguation was brought forward in The EU MEANING

project in 2002.

It used the assumption that within a domain, words often have a single

meaning, and that domains are identifiable on the Web. This was further

explored by using Web technology to gather manual word sense annotations

on the Word Expert Web site.

In areas of language modeling,

the Web has been used to address data sparseness. Lexical statistics

have been gathered for resolving prepositional phrase attachments, while Web document were used to seek a balance in the corpus.

In areas of information retrieval, a Web track was integrated as a

component in the community’s TREC evaluation initiative. The sample of

the Web used for this exercise amount to around 100GB, compromising of

largely documents in the .gov top level domain.

British National Corpus

The British National Corpus contains ample information on the dominant meanings and usage patterns for the 10,000 words that forms the core of English.

The number of words in the British National Corpus (ca 100

million) is sufficient for many empirical strategies for learning about

language for linguists and lexicographers, and is satisfactory for technologies that utilize quantitative information about the behavior of words as input (parsing).

However, for some other purposes, it is insufficient, as an outcome of the Zipfian

nature of word frequencies. Because the bulk of the lexical stock

occurs less than 50 times in the British National Corpus, it is

insufficient for statistically stable conclusions about such words.

Furthermore, for some rarer words, rare meanings of common words, and

combinations of words, no data has been found. Researchers find that

probabilistic models of language based on very large quantities of data

are better than ones based on estimates from smaller, cleaner data sets.

The multilingual Web

The Web is clearly a multilingual corpus.

It is estimated that 71% of the pages (453 million out of 634 million

Web pages indexed by the Excite engine) were written in English,

followed by Japanese (6.8%), German (5.1%), French (1.8%), Chinese

(1.5%), Spanish (1.1%), Italian (0.9%), and Swedish (0.7%).

A test to find contiguous words like ‘deep breath’ revealed 868,631 Web pages containing the terms in AlltheWeb.

The number found through the search engines are more than three times

the counts generated by the British National Corpus, indicating the

significant size of the English corpus available on the Web.

The massive size of text available on the Web can be seen in the

analysis of controlled data in which corpora of different languages were

mixed in various proportions. The estimated Web size in words by AltaVista

saw English at the top of the list with 76,598,718,000 words. The next

is German, with 7,035,850,000 words along with 6 other languages with

over a billion hits. Even languages with fewer hits on the Web such as

Slovenian, Croatian, Malay, and Turkish have more than one hundred

million words on the Web.

This reveals the potential strength and accuracy of using the Web as a

Corpus given its significant size, which warrants much additional

research such as the project currently being carried out by the British

National Corpus to exploit its scale.

Challenges

In

areas of language modeling, there are limitations on the applicability

of any language model as the statistics for different types of text will

be different.

When a language technology application is put into use (applied to a

new text type), it is not certain that the language model will fare in

the same way as how it would when applied to the training corpus. It is

found that there are substantial variations in model performance when

the training corpus changes. This lack of theory types limits the assessment of the usefulness of language-modeling work.

As Web texts are easily produced (in terms of cost and time) and

with many different authors working on them, it often results in little

concern for accuracy. Grammatical and typographical errors are regarded

as “erroneous” forms that cause the Web to be a dirty corpus.

Nonetheless, it may still be useful even with some noise.

The issue of whether sublanguages

should be included remains unsettled. Proponents of it argue that with

all sublanguages removed, it will result in an impoverished view of

language. Since language is made up of lexicons, grammar and a wide

array of different sublanguages, they should be included. However, it is

not until recently that it became a viable option. Striking a middle

ground by including some sublanguages is contentious because it’s an

arbitrary issue of which to include and which not.

The decision of what to include in a corpus lies with corpus developers, and it has been done so with pragmatism.

The desiderata and criteria used for the British National Corpus serves

as a good model for a general-purpose, general-language corpus with the focus of being representative replaced with being balanced.

Search engines such as Google

serves as a default means of access to the Web and its wide array of

linguistics resources. However, for linguists working in the field of

corpora, there presents a number of challenges. This includes the

limited instances that are presented by the search engines (1,000 or

5,000 maximum); insufficient context for each instance (Google provides a

fragment of around ten words); results selected according to criteria

that are distorted (from a linguistic point of view) as search term in

titles and headings often occupy the top results slots; inability to

allow searches to be specified according to linguistic criteria, such as

the citation form for a word, or word class; unreliability of

statistics, with results varying according to search engine load and

many other factors. At present, in view of the conflicts of priorities

among the different stakeholders, the best solution is for linguists to

attempt to correct these problems by themselves. This will then lead to a

large number of possibilities opening in the area of harnessing the

rich potential of the Web.

Representation

Despite

the sheer size of the Web, it may still not be representative of all

the languages and domains in the world, and neither are other corpora.

However, the huge quantities of text, in numerous languages and language

types on a huge range of topics makes it a good starting point that

opens up to a large number of possibilities in the study of corpora.

Impact of its spread and influence

Stylistics

arising from Internet usage has spread beyond the new media into other

areas and platforms, including but not limited to, films, music and literary works.

The infiltration of Internet stylistics is important as mass audiences

are exposed to the works, reinforcing certain Internet specific language

styles which may not be acceptable in standard or more formal forms of

language.

Apart from internet slang, grammatical errors and typographical

errors are features of writing on the Internet and other CMC channels.

As users of the Internet gets accustomed to these errors, it

progressively infiltrates into everyday language use, in both written

and spoken forms.

It is also common to witness such errors in mass media works, from

typographical errors in news articles to grammatical errors in

advertisements and even internet slang in drama dialogues.

The more the internet is incorporated into daily life, the

greater the impact it has on formal language. This is especially true in

modern Language Arts classes through the use of smart phones, tablets,

and social media. Students are exposed to the language of the internet

more than ever, and as such, the grammatical structure and slang of the

internet are bleeding into their formal writing. Full immersion into a

language is always the best way to learn it. Mark Lester in his book Teaching Grammar and Usage

states, “The biggest single problem that basic writers have in

developing successful strategies for coping with errors is simply their

lack of exposure to formal written English...We would think it absurd to

expect a student to master a foreign language without extensive

exposure to it.” Since students are immersed in internet language, that is the form and structure they are mirroring.

Mass media

There

has been instances of television advertisements using Internet slang,

reinforcing the penetration of Internet stylistics in everyday language

use. For example, in the Cingular

commercial in the United States, acronyms such as "BFF Jill" (which

means "Best Friend Forever, Jill") were used. More businesses have

adopted the use of Internet slang in their advertisements as the more

people are growing up using the Internet and other CMC platforms, in an

attempt to relate and connect to them better. Such commercials have received relatively enthusiastic feedback from its audiences.

The use of Internet lingo has also spread into the arena of music, significantly seen in popular music. A recent example is Trey Songz's lyrics for "LOL :-)", which incorporated many Internet lingo and mentions of Twitter and texting.

The spread of Internet linguistics is also present in films made by both commercial and independent filmmakers. Though primarily screened at film festivals,

DVDs of independent films are often available for purchase over the

internet including paid-live-streamings, making access to films more

easily available for the public.

The very nature of commercial films being screened at public cinemas

allows for the wide exposure to the mainstream mass audience, resulting

in a faster and wider spread of Internet slangs. The latest commercial

film is titled "LOL" (acronym for Laugh Out Loud or Laughing Out Loud), starring Miley Cyrus and Demi Moore. This movie is a 2011 remake of the Lisa Azuelos' 2008 popular French film similarly titled "LOL (Laughing Out Loud)".

The use of internet slangs is not limited to the English language but extends to other languages as well. The Korean language

has incorporated the English alphabet in the formation of its slang,

while others were formed from common misspellings arising from fast

typing. The new Korean slang is further reinforced and brought into everyday language use by television shows such as soap operas or comedy dramas like “High Kick Through the Roof” released in 2009.

Linguistic future of the Internet

With

the emergence of greater computer/Internet mediated communication

systems, coupled with the readiness with which people adapt to meet the

new demands of a more technologically sophisticated world, it is

expected that users will continue to remain under pressure to alter

their language use to suit the new dimensions of communication.

As the number of Internet users increase rapidly around the

world, the cultural background, linguistic habits and language

differences among users are brought into the Web at a much faster pace.

These individual differences among Internet users are predicted to

significantly impact the future of Internet linguistics, notably in the

aspect of the multilingual web. As seen from 2000 to 2010, Internet

penetration has experienced its greatest growth in non-English speaking

countries such as China and India and countries in Africa, resulting in more languages apart from English penetrating the Web.

Also, the interaction between English and other languages is predicted to be an important area of study.

As global users interact with each other, possible references to

different languages may continue to increase, resulting in formation of

new Internet stylistics that spans across languages. Chinese and Korean

languages have already experienced English language's infiltration

leading to the formation of their multilingual Internet lingo.

At current state, the Internet provides a form of education and

promotion for minority languages. However, similar to how cross-language

interaction has resulted in English language's infiltration into

Chinese and Korean languages to form new slangs,

minority languages are also affected by the more common languages used

on the Internet (such as English and Spanish). While language

interaction can cause a loss in the authentic standard of minority

languages, familiarity of the majority language can also affect the

minority languages in adverse ways.

For example, users attempting to learn the minority language may opt to

read and understand about it in a majority language and stop there,

resulting in a loss instead of gain in the potential speakers of the

minority language.

Also, speakers of minority languages may be encouraged to learn the

more common languages that are being used on the Web in order to gain

access to more resources, and in turn leading to a decline in their

usage of their own language. The future of endangered minority languages in view of the spread of Internet remains to be observed.