Total U.S. incarceration by year

A

graph showing the incarceration rate under state and federal

jurisdiction per 100,000 population 1925–2013. Does not include

unsentenced inmates, nor inmates in local jails.

Inmates held in custody in state or federal prisons or in local jails. From U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Incarceration in the United States is one of the main forms of punishment and rehabilitation for the commission of felony and other offenses. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, and the highest per-capita incarceration rate.

In 2016 in the US, there were 655 people incarcerated per 100,000

population. This is the US incarceration rate for adults or people tried

as adults.

In 2016, 2.2 million Americans have been incarcerated, which means for

every 100,000 there are 655 that are currently inmates. This costs the

United States government $80 billion dollars a year.

Additionally, 4,751,400 adults in 2013 (1 in 51) were on probation or on parole.

In total, 6,899,000 adults were under correctional supervision

(probation, parole, jail, or prison) in 2013 – about 2.8% of adults (1

in 35) in the U.S. resident population.

In 2014, the total number of persons in the adult correctional systems

had fallen to 6,851,000 persons, approximately 52,200 fewer offenders

than at the year-end of 2013 as reported by the BJS. About 1 in 36

adults (or 2.8% of adults in the US) were under some form of

correctional supervision – the lowest rate since 1996. On average, the

correctional population has declined by 1.0% since 2007; while this

continued to stay true in 2014 the number of incarcerated adults

slightly increased in 2014.

In 2016, the total number of persons in U.S. adult correctional systems

was an estimated 6,613,500. From 2007 to 2016, the correctional

population decreased by an average of 1.2% annually. By the end of 2016,

approximately 1 in 38 persons in the United States were under

correctional supervision.

In addition, there were 54,148 juveniles in juvenile detention in 2013.

Although debtor's prisons no longer exist in the United States, residents of some U.S. states can still be incarcerated for debt as of 2016. The Vera Institute of Justice

reported in 2015 that majority of those incarcerated in local and

county jails are there for minor violations, and have been jailed for

longer periods of time over the past 30 years because they are unable to

pay court-imposed costs.

According to a 2014 Human Rights Watch report, "tough-on-crime" laws adopted since the 1980s, have filled U.S. prisons with mostly nonviolent offenders. However, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that, as of the end of 2015, 54% of state prisoners sentenced to

more than 1 year were serving time for a violent offense. Fifteen percent of state prisoners at year-end 2015

had been convicted of a drug offense as their most serious. In comparison, 47% of federal prisoners serving

time in September 2016 (the most recent date for which data are available) were convicted of a drug offense.

This policy failed to rehabilitate prisoners and many were worse on

release than before incarceration. Rehabilitation programs for offenders

can be more cost effective than prison. According to a 2015 study by the Brennan Center for Justice, falling crime rates cannot be ascribed to mass incarceration. Conversely, Steven Levitt asserted in a 2004 paper that, among other factors that also affected the crime rate, approximately one third of the observed crime drop in the 1990s was due to incarceration.

History

Throughout the 1500s, the people of England considered idleness to be

the cause of many crimes, and therefore found the solution to be

creating workhouses as a system to rehabilitate criminals. Though many

of the first people, especially in the foundation of these "houses of

correction" were actually vagrants without homes. Later, in the 1700s,

English philanthropists began to focus on the reform of convicted

criminals in prisons, which they believed needed a chance to become

morally pure in order to stop or slow crime. Since at least 1740, some

of these philosophers began thinking of solitary confinement as a way to

create and maintain spiritually clean people in prisons. As English

people immigrated to North America, so did these theories of penology.

Spanish colonizers also brought ideas on confinement. Spanish soldiers in St. Augustine, Florida built the first substantial prison.

Some of the first structures built in English-settled America

were jails, and by the 18th century, every English North American county

had a jail. These jails served a variety of functions such as a holding

place for debtors, prisoners-of-war, and political prisoners, those

bound in the penal transportation and slavery systems, and of those

accused-of but not tried for crimes.

Sentences for those convicted of crimes were rarely longer than three

months, and often lasted only a day. Poor citizens were often imprisoned

for longer than their richer neighbors, as bail was rarely not

accepted.

In 1841, Dorothea Dix discovered that prison conditions in the US were, in her opinion, inhumane.

Prisoners were chained naked, whipped with rods. Others, criminally

insane, were caged, or placed in cellars, or closets. She insisted on

changes throughout the rest of her life. While focusing on the insane,

her comments also resulted in changes for other inmates.

Prison systems

In the United States criminal law is a concurrent power.

Individuals who violate state laws and/or territorial laws generally are placed in state or territorial prisons, while those who violate United States federal law are generally placed in federal prisons operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), an agency of the United States Department of Justice (USDOJ). The BOP also houses adult felons convicted of violating District of Columbia laws due to the National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act of 1997.

As of 2004, state prisons proportionately house more violent

felons, so state prisons in general gained a more negative reputation

compared to federal prisons.

In 2016, almost 90% of prisoners were in state prisons; 10% were in federal prisons.

At sentencing in federal court, judges use a point system to

determine which inmate goes into which housing branch. This helps

federal law employees to determine who goes to which facility and to

which punishing housing unit to send them. Another method to determine

housing is the admission committees. In prisons, multiple people come

together to determine to which housing unit an inmate belongs. People

like the case manager, psychologist, and social worker have a voice in

what is appropriate for the inmate.

Prison populations

As of 2016, 2.3 million people were incarcerated in the United States, at a rate of 698 people per 100,000. Total US incarceration peaked in 2008. Total correctional population (prison, jail, probation, parole) peaked in 2007. In 2008 the US had around 24.7% of the world's 9.8 million prisoners.

In 2016, almost 7 million people were under some type of control

by the correction industry (incarcerated, on probation or parole, etc). 3.6 million of those people were on probation and 840,000 were on parole. In recent decades the U.S. has experienced a surge in its prison population, quadrupling since 1980, partially as a result of mandatory sentencing that came about during the "War on Drugs."

Nearly 53,000 youth were incarcerated in 2015.

4,656 of those were held in adult facilities, while the rest were in

juvenile facilities. Of those in juvenile facilities, 69% are 16 or

older, while over 500 are 12 or younger. The Prison Policy Initiative

broke down those numbers, finding that "black and American Indian youth

are overrepresented in juvenile facilities while white youth are

underrepresented."

Black youth comprise 14% of the national youth population, but "43% of

boys and 34% of girls in juvenile facilities are Black. And even

excluding youth held in Indian country facilities, American Indians make

up 3% of girls and 1.5% of boys in juvenile facilities, despite

comprising less than 1% of all youth nationally."

As of 2009, the three states with the lowest ratios of imprisoned people per 100,000 population are Maine (150 per 100,000), Minnesota (189 per 100,000), and New Hampshire (206 per 100,000). The three states with the highest ratio are Louisiana (881 per 100,000), Mississippi (702 per 100,000) and Oklahoma (657 per 100,000). A 2018 study by the Prison Policy Initiative placed Oklahoma's incarceration rate as 1,079, supplanting Louisiana (with a rate of 1,052) as "the world's prison capital."

A 2005 report estimated that 27% of federal prison inmates are

noncitizens, convicted of crimes while in the country legally or

illegally.

However, federal prison inmates account for six percent of the total

incarcerated population; noncitizen populations in state and local

prisons are more difficult to establish.

Duration

Many legislatures continually have reduced discretion of judges in

both the sentencing process and the determination of when the conditions

of a sentence have been satisfied. Determinate sentencing, use of mandatory minimums, and guidelines-based sentencing continue to remove the human element from sentencing, such as the prerogative of the judge to consider the mitigating or extenuating circumstances of a crime to determine the appropriate length of the incarceration. As the consequence of "three strikes laws,"

the increase in the duration of incarceration in the last decade was

most pronounced in the case of life prison sentences, which increased by

83% between 1992 and 2003 while violent crimes fell in the same period.

Violent and nonviolent crime

In 2016, there were an estimated 1.2 million violent crimes committed in the United States.

Over the course of that year, U.S. law enforcement agencies made

approximately 10.7 million arrests, excluding arrests for traffic

violations. In that year, approximately 2.3 million people were incarcerated in jail or prison.

Felony Sentences in State Courts, study by the United States Department of Justice

As of September 30, 2009 in federal prisons, 7.9% of sentenced prisoners were incarcerated for violent crimes, while at year end 2008 of sentenced prisoners in state prisons, 52.4% had been jailed for violent crimes.

In 2002 (latest available data by type of offense), 21.6% of convicted

inmates in jails were in prison for violent crimes. Among unconvicted

inmates in jails in 2002, 34% had a violent offense as the most serious

charge. 41% percent of convicted and unconvicted jail inmates in 2002

had a current or prior violent offense; 46% were nonviolent recidivists.

From 2000 to 2008, the state prison population increased by

159,200 prisoners, and violent offenders accounted for 60% of this

increase. The number of drug offenders

in state prisons declined by 12,400 over this period. Furthermore,

while the number of sentenced violent offenders in state prison

increased from 2000 through 2008, the expected length of stays for these

offenders declined slightly during this period.

In 2016, about 200,000, under 16%, of the 1.3 million people in

state jails, were serving time for drug offenses. 700,000 were

incarcerated for violent offenses.

Violent crime was not responsible for the quadrupling of the

incarcerated population in the United States from 1980 to 2003. Violent

crime rates had been relatively constant or declining over those

decades. The prison population was increased primarily by public policy

changes causing more prison sentences and lengthening time served, for

example through mandatory minimum sentencing, "three strikes" laws, and

reductions in the availability of parole or early release. 49% of

sentenced state inmates were held for violent offenses.

Perhaps the single greatest force behind the growth of the prison population has been the national "War on Drugs".

The War on Drugs initiative expanded during the presidency of Ronald

Reagan. During Regan's term, a bi-partisan Congress established the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, galvanized by the death of Len Bias. According to the Human Rights Watch,

legislation like this led to the extreme increase in drug offense

imprisonment and "increasing racial disproportions among the arrestees".

The number of incarcerated drug offenders has increased twelvefold

since 1980. In 2000, 22 percent of those in federal and state prisons

were convicted on drug charges.

In 2011, 55.6% of the 1,131,210 sentenced prisoners in state prisons

were being held for violent crimes (this number excludes the 200,966

prisoners being held due parole violations, of which 39.6% were

re-incarcerated for a subsequent violent crime).

Also in 2011, 3.7% of the state prison population consisted of

prisoners whose highest conviction was for drug possession (again

excluding those incarcerated for parole violations of which 6.0% were

re-incarcerated for a subsequent act of drug possession).

Recidivism

A 2002 study survey, showed that among nearly 275,000 prisoners

released in 1994, 67.5% were rearrested within 3 years, and 51.8% were

back in prison. However, the study found no evidence that spending more time in prison raises the recidivism

rate, and found that those serving the longest time, 61 months or more,

had a slightly lower re-arrest rate (54.2%) than every other category

of prisoners. This is most likely explained by the older average age of

those released with the longest sentences, and the study shows a strong

negative correlation between recidivism and age upon release. According

to the Bureau of Justice Statistics,

a study was conducted that tracked 404,638 prisoners in 30 states after

their release from prison in 2005. From the examination it was found

that within three years after their release 67.8% of the released

prisoners were rearrested; within five years, 76.6% of the released

prisoners were rearrested, and of the prisoners that were rearrested

56.7% of them were rearrested by the end of their first year of release.

Comparison with other countries

A map of incarceration rates by country

With around 100 prisoners per 100,000, the United States had an

average prison and jail population until 1980. Afterwards it drifted

apart considerably. The United States has the highest prison and jail

population (2,121,600 in adult facilities in 2016), and the highest

incarceration rate in the world (655 per 100,000 population in 2016).

According to the World Prison Population List (11th edition) there were

around 10.35 million people in penal institutions worldwide in 2015. The US had 2,173,800 prisoners in adult facilities in 2015.

That means the US held 21.0% of the world's prisoners in 2015, even

though the US represented only around 4.4 percent of the world's

population in 2015.

Comparing other English-speaking developed countries, whereas the

incarceration rate of the US is 655 per 100,000 population of all ages, the incarceration rate of Canada is 114 per 100,000 (as of 2015), England and Wales is 146 per 100,000 (as of 2016), and Australia is 160 per 100,000 (as of 2016). Comparing other developed countries, the rate of Spain is 133 per 100,000 (as of 2016), Greece is 89 per 100,000 (as of 2016), Norway is 73 per 100,000 (as of 2016), Netherlands is 69 per 100,000 (as of 2014), and Japan is 48 per 100,000 (as of 2014).

A 2008 New York Times article,

said that "it is the length of sentences that truly distinguishes

American prison policy. Indeed, the mere number of sentences imposed

here would not place the United States at the top of the incarceration

lists. If lists were compiled based on annual admissions to prison per

capita, several European countries would outpace the United States. But

American prison stays are much longer, so the total incarceration rate

is higher."

The U.S. incarceration rate peaked in 2008 when about 1 in 100 US adults was behind bars. This incarceration rate exceeded the average incarceration levels in the Soviet Union during the existence of the Gulag system, when the Soviet Union's population reached 168 million, and 1.2 to 1.5 million people were in the Gulag prison camps and colonies (i.e. about 0.8 imprisoned per 100 USSR residents, according to numbers from Anne Applebaum and Steven Rosefielde). In The New Yorker article The Caging of America (2012), Adam Gopnik

writes: "Over all, there are now more people under 'correctional

supervision' in America—more than six million—than were in the Gulag Archipelago under Stalin at its height."

Ethnicity

The 2015 US prison population by race, ethnicity, and gender. Does not include jails.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics

(BJS) in 2013 black males accounted for 37% of the total male prison

population, white males 32%, and Hispanic males 22%. White females

comprised 49% of the prison population in comparison to black females

who accounted for 22% of the female population. The imprisonment rate

for black females (113 per 100,000) was 2x the rate for white females

(51 per 100,000. Out of all ethnic groups, African Americans, Puerto Rican Americans, and Native Americans have some of the highest rates of incarceration.

Though, of these groups, the black population is the largest, and

therefore make up a large portion of those incarcerated in US prisons

and jails.

Hispanics (of all races) were 20.6% of the total jail and prison population in 2009. Hispanics comprised 16.3% of the US population according to the 2010 US census. The Northeast has the highest incarceration rates of Hispanics in the nation.

Connecticut has the highest Hispanic-to-White incarceration ratio with

6.6 Hispanic males for every white male. The National Average

Hispanic-to-White incarceration ratio is 1.8. Other states with high

Hispanic-to-White incarcerations include Massachusetts, Pennsylvania,

and New York.

In 2010, adult black non-Hispanic males were incarcerated at the

rate of 4,347 inmates per 100,000 U.S. residents. Adult white males were

incarcerated at the rate of 678 inmates per 100,000 U.S. residents.

Adult Hispanic males were incarcerated at the rate of 1,755 inmates per

100,000 U.S. residents.

(For female rates see the table below.) Asian Americans have lower

incarceration rates than any other racial group, including whites.

There is general agreement in the literature that blacks are more

likely to be arrested for violent crimes than whites in the United

States. Whether this is the case for less serious crimes is less clear.

Black majority cities have similar crime statistics for blacks as do

cities where majority of population is white. For example,

white-plurality San Diego has a slightly lower crime rate for blacks

than does Atlanta, a city which has black majority in population and

city government.

In 2013, by age 18, 30% of black males, 26% of Hispanic males,

and 22% of white males have been arrested. By age 23, 49% of black

males, 44% of Hispanic males, and 38% of white males have been arrested.

According to Attorney Antonio Moore in his Huffington Post article,

"there are more African American men incarcerated in the U.S. than the

total prison populations in India, Argentina, Canada, Lebanon, Japan,

Germany, Finland, Israel and England combined." There are only 19

million African American males in the United States, but collectively

these countries represent over 1.6 billion people. Moore has also shown using data from the World Prison Brief & United States Department of Justice

that there are more black males incarcerated in the United States than

all women imprisoned globally. To give perspective there are just about 4

billion woman in total globally, there are only 19 million black males

of all ages in the United States.

Gender

In 2013, there were 102,400 adult females in local jails in the

United States, and 111,300 adult females in state and federal prisons.

Within the US, the rate of female incarceration increased fivefold in a

two decade span ending in 2001; the increase occurred because of

increased prosecutions and convictions of offenses related to recreational drugs, increases in the severities of offenses, and a lack of community sanctions and treatment for women who violate laws. In the United States, authorities began housing women in correctional facilities separate from men in the 1870s.

In 2013, there were 628,900 adult males in local jails in the

United States, and 1,463,500 adult males in state and federal prisons.

In a study of sentencing in the United States in 1984, David B. Mustard

found that males received 12 percent longer prison terms than females

after "controlling for the offense level, criminal history, district,

and offense type," and noted that "females receive even shorter

sentences

relative to men than whites relative to blacks." A later study by Sonja B. Starr found sentences for men to be up to 60% higher when controlling for more variables.

Several explanations for this disparity have been offered, including

that women have more to lose from incarceration, and that men are the

targets of discrimination in sentencing.

Youth

Through the juvenile courts and the adult criminal justice

system, the United States incarcerates more of its youth than any other

country in the world, a reflection of the larger trends in

incarceration practices in the United States. This has been a source of

controversy for a number of reasons, including the overcrowding and

violence in youth detention facilities, the prosecution of youths as

adults and the long term consequences of incarceration on the

individual's chances for success in adulthood. In 2014, the United Nations Human Rights Committee criticized the United States for about ten judicial abuses, including the mistreatment of juvenile inmates.

A UN report published in 2015 criticized the US for being the only

nation in the world to sentence juveniles to life imprisonment without

parole.

According to federal data from 2011, around 40% of the nation's juvenile inmates are housed in private facilities.

The incarceration of youths has been linked to the effects of

family and neighborhood influences. One study found that the "behaviors

of family members and neighborhood peers appear to substantially affect

the behavior and outcomes of disadvantaged youths".

Aged

The

percentage of prisoners in federal and state prisons aged 55 and older

increased by 33% from 2000 to 2005 while the prison population grew by

8%. The Southern Legislative Conference

found that in 16 southern states, the elderly prisoner population

increased on average by 145% between 1997 and 2007. The growth in the

elderly population brought along higher health care costs, most notably

seen in the 10% average increase in state prison budgets from 2005 to

2006.

The SLC expects the percentage of elderly prisoners relative to

the overall prison population to continue to rise. Ronald Aday, a

professor of aging studies at Middle Tennessee State University and author of Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections, concurs. One out of six prisoners in California is serving a life sentence. Aday predicts that by 2020 16% percent of those serving life sentences will be elderly.

State governments pay all of their inmates' housing costs which

significantly increase as prisoners age. Inmates are unable to apply for

Medicare and Medicaid. Most Departments of Correction report spending more than 10 percent of the annual budget on elderly care.

The American Civil Liberties Union

published a report in 2012 which asserts that the elderly prison

population has climbed 1300% since the 1980s, with 125,000 inmates aged

55 or older now incarcerated.

LGBT people

LGBT

(lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender) youth are disproportionately

more likely than the general population to come into contact with the criminal justice system. According to the National Center for Transgender Equality, 16 percent of transgender adults have been in prison and/or jail, compared to 2.7 percent of all adults.

It has also been found that 13–15 percent of youth in detention

identify as LGBT, whereas an estimated 4-8 percent of the general youth

population identify as such.

The reasons behind these disproportionate numbers are multi-faceted and complex. Poverty, homelessness, profiling by law enforcement, and imprisonment are disproportionately experienced by transgender and gender non-conforming people. LGBT youth not only experience these same challenges, but many also live in homes unwelcoming to their identities.

This often results in LGBT youth running away and/or engaging in

criminal activities, such as the drug trade, sex work, and/or theft,

which places them at higher risk for arrest. Because of discriminatory

practices and limited access to resources, transgender adults are also

more likely to engage in criminal activities to be able to pay for

housing, health care, and other basic needs.

LGBT people in jail and prison are particularly vulnerable to mistreatment by other inmates and staff. This mistreatment includes solitary confinement

(which may be described as "protective custody"), physical and sexual

violence, verbal abuse, and denial of medical care and other services.

According to the National Inmate Survey, in 2011–12, 40 percent of

transgender inmates reported sexual victimization compared to 4 percent

of all inmates.

Mental illness

In the United States, the percentage of inmates with mental illness has been steadily increasing, with rates more than quadrupling from 1998 to 2006. Many have attributed this trend to the deinstitutionalization of mentally ill persons beginning in the 1960s, when mental hospitals across the country began closing their doors.

However, other researchers indicate that "there is no evidence for the

basic criminalization premise that decreased psychiatric services

explain the disproportionate risk of incarceration for individuals with

mental illness".

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics,

over half of all prisoners in 2005 had experienced mental illness as

identified by "a recent history or symptoms of a mental health problem";

of this population, jail inmates experienced the highest rates of

symptoms of mental illness at 60 percent, followed by 49 percent of

state prisoners and 40 percent of federal prisoners.

Not only do people with recent histories of mental illness end up

incarcerated, but many who have no history of mental illness end up

developing symptoms while in prison. In 2006, the Bureau of Justice

Statistics found that a quarter of state prisoners had a history of

mental illness, whereas 3 in 10 state prisoners had developed symptoms

of mental illness since becoming incarcerated with no recent history of

mental illness.

According to Human Rights Watch, one of the contributing factors to the disproportionate rates of mental illness in prisons and jails is the increased use of solitary confinement,

for which "socially and psychologically meaningful contact is reduced

to the absolute minimum, to a point that is insufficient for most

detainees to remain mentally well functioning".

Another factor to be considered is that most inmates do not get the

mental health services that they need while incarcerated. Due to limited

funding, prisons are not able to provide a full range of mental health

services and thus are typically limited to inconsistent administration

of psychotropic medication, or no psychiatric services at all.

Human Rights Watch also reports that corrections officers routinely use

excessive violence against mentally ill inmates for nonthreatening

behaviors related to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Inmates are often shocked, shackled and pepper sprayed.

Although many argue that prisons have become the facilities for

the mentally ill, very few crimes point directly to symptoms of mental

illness as their sole cause. Despite the disproportionate representation of mentally ill persons in prison, a study by American Psychological Association indicates that only 7.5 percent of crimes committed were found to be directly related to mental illness.

However, some advocates argue that many incarcerations of mentally ill

persons could have been avoided if they had been given proper treatment, which would be a much less costly alternative to incarceration.

Mental illness rarely stands alone when analyzing the risk factors associated with incarceration and recidivism rates.

The American Psychological Association recommends a holistic approach

to reducing recidivism rates among offenders by providing

"cognitive–behavioral treatment focused on criminal cognition" or

"services that target variable risk factors for high-risk offenders" due

to the numerous intersecting risk factors experienced by mentally ill

and non-mentally ill offenders alike.

To prevent the recidivism of individuals with mental illness, a

variety of programs are in place that are based on criminal justice or

mental health intervention models. Programs modeled after criminal

justice strategies include diversion programs, mental health courts, specialty mental health probation or parole, and jail aftercare/prison re-entry. Programs modeled after mental health interventions include forensic assertive community treatment and forensic intensive case management.

It has been argued that the wide diversity of these program

interventions points to a lack of clarity on which specific program

components are most effective in reducing recidivism rates among

individuals with mental illness.

Students

The

term "school-to-prison-pipeline", also known as the

"schoolhouse-to-jailhouse track", is a concept that was named in the

1980s. The school-to-prison pipeline is the idea that a school's harsh

punishments—which typically push students out of the classroom—lead to

the criminalization of students' misbehaviors and result in increasing a

student's probability of entering the prison system. Although the school-to-prison pipeline is aggravated by a combination of ingredients, zero-tolerance policies are viewed as main contributors.

Zero-tolerance policies are regulations that mandate specific

consequences in response to outlined student misbehavior, typically

without any consideration for the unique circumstances surrounding a

given incident.

Zero-tolerance policies both implicitly and explicitly usher the

student into the prison track. Implicitly, when a student is extracted

from the classroom, the more likely that student is to drop out of

school as a result of being in class less. As a dropout, that child is

then ill-prepared to obtain a job and become a fruitful citizen. Explicitly, schools sometimes do not funnel their pupils to the prison systems inadvertently; rather, they send them directly.

Once in juvenile court, even sympathetic judges are not likely to

evaluate whether the school's punishment was warranted or fair. For

these reasons, it is argued that zero-tolerance policies lead to an

exponential increase in the juvenile prison populations.

The national suspension rate doubled from 3.7% to 7.4% from 1973 to 2010.

The claim that Zero Tolerance Policies affect students of color at a

disproportionate rate is supported in the Code of Maryland Regulations

study that found black students were suspended at more than double the

rate of white students. This trend can be seen throughout numerous studies of this type of material and particularly in the south.

Furthermore, between 1985 and 1989, there was an increase in referrals

of minority youth to juvenile court, petitioned cases, adjudicated

delinquency cases, and delinquency cases placed outside the home.

During this time period, the number of African American youth detained

increased by 9% and the number of Hispanic youth detained increased by

4%, yet the proportion of White youth declined by 13%. Documentation of this phenomenon can be seen as early as 1975 with the book School Suspensions: Are they helping children?

Transfer treaty

The BOP receives all prisoner transfer treaty

inmates sent from foreign countries, even if their crimes would have

been, if committed in the United States, tried in state, DC, or

territorial courts.

Non-US citizens incarcerated in federal and state prisons are eligible

to be transferred to their home countries if they qualify.

Operational

U.S. federal prisoner distribution since 1950

Security levels

In some, but not all, states' department of corrections, inmates

reside in different facilities that vary by security level, especially

in security measures, administration of inmates, type of housing, and

weapons and tactics used by corrections officers. The federal government's Bureau of Prisons

uses a numbered scale from one to five to represent the security level.

Level five is the most secure, while level one is the least. State

prison systems operate similar systems. California, for example,

classifies its facilities from Reception Center through Levels I to V

(minimum to maximum security) to specialized high security units (all

considered Level V) including Security Housing Unit (SHU)—California's version of supermax—and

related units. As a general rule, county jails, detention centers, and

reception centers, where new commitments are first held while either

awaiting trial or before being transferred to "mainline" institutions to

serve out their sentences, operate at a relatively high level of

security, usually close security or higher.

Supermax prison

facilities provide the highest level of prison security. These units

hold those considered the most dangerous inmates, as well as inmates

that have been deemed too high-profile or too great a national security

risk for a normal prison. These include inmates who have committed

assaults, murders, or other serious violations in less secure

facilities, and inmates known to be or accused of being prison gang

members. Most states have either a supermax section of a prison

facility or an entire prison facility designated as a supermax. The United States Federal Bureau of Prisons operates a federal supermax, A.D.X. Florence, located in Florence, Colorado, also known as the "Alcatraz of the Rockies"

and widely considered to be perhaps the most secure prison in the

United States. A.D.X. Florence has a standard supermax section where

assaultive, violent, and gang-related inmates are kept under normal

supermax conditions of 23-hour confinement and abridged amenities.

A.D.X. Florence is considered to be of a security level above that of

all other prisons in the United States, at least in the "ideological"

ultramax part of it, which features permanent, 24-hour solitary confinement with rare human contacts or opportunity to earn better conditions through good behavior.

In a maximum security prison or area (called high security in the federal system), all prisoners have individual cells

with sliding doors controlled from a secure remote control station.

Prisoners are allowed out of their cells one out of twenty four hours

(one hour and 30 minutes for prisoners in California). When out of their

cells, prisoners remain in the cell block or an exterior cage. Movement

out of the cell block or "pod" is tightly restricted using restraints

and escorts by correctional officers.

U.S. state prisoner distribution in 2016; excludes jail inmates. Data Source: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6226

Under close security, prisoners usually have one- or

two-person cells operated from a remote control station. Each cell has

its own toilet and sink. Inmates may leave their cells for work

assignments or correctional programs and otherwise may be allowed in a

common area in the cellblock or an exercise yard. The fences are

generally double fences with watchtowers housing armed guards, plus

often a third, lethal-current electric fence in the middle.

Prisoners that fall into the medium security group may sleep in cells, but share them two and two, and use bunk beds with lockers to store their possessions. The cell may have showers, toilets and sinks, but it's not a strictly enforced rule.

Cells are locked at night with one or more correctional officers

supervising. There is less supervision over the internal movements of

prisoners. The perimeter is generally double fenced and regularly

patrolled.

Prisoners in minimum security facilities are considered to pose little physical risk to the public and are mainly non-violent "white collar criminals". Minimum security prisoners live in less-secure dormitories,

which are regularly patrolled by correctional officers. As in medium

security facilities, they have communal showers, toilets, and sinks. A

minimum-security facility generally has a single fence that is watched,

but not patrolled, by armed guards. At facilities in very remote and

rural areas, there may be no fence at all. Prisoners may often work on

community projects, such as roadside litter cleanup with the state

department of transportation or wilderness conservation. Many minimum

security facilities are small camps located in or near military bases,

larger prisons (outside the security perimeter) or other government

institutions to provide a convenient supply of convict labor to the

institution. Many states allow persons in minimum-security facilities

access to the Internet.

Correspondence

Research

indicates that inmates who maintain contact with family and friends in

the outside world are less likely to be convicted of further crimes and

usually have an easier reintegration period back into society.

Many institutions encourage friends and families to send letters,

especially when they are unable to visit regularly. However, guidelines

exist as to what constitutes acceptable mail, and these policies are

strictly enforced.

Mail sent to inmates in violation of prison policies can result in sanctions such as loss of imprisonment time reduced for good behavior. Most Department of Corrections

websites provide detailed information regarding mail policies. These

rules can even vary within a single prison depending on which part of

the prison an inmate is housed. For example, death row and maximum security inmates are usually under stricter mail guidelines for security reasons.

There have been several notable challenges to prison corresponding services. The Missouri Department of Corrections (DOC) stated that effective June 1, 2007, inmates would be prohibited from using pen pal websites, citing concerns that inmates were using them to solicit money and defraud the public. Service providers such as WriteAPrisoner.com, together with the ACLU,

plan to challenge the ban in Federal Court. Similar bans on an inmate's

rights or a website's right to post such information has been ruled

unconstitutional in other courts, citing First Amendment freedoms.

Some faith-based initiatives promote the positive effects of

correspondence on inmates, and some have made efforts to help

ex-offenders reintegrate into society through job placement assistance. Inmates' ability to mail letters to other inmates has been limited by the courts.

Inmate correspondence with members of society is typically encouraged

because of the positive impact it can have on inmates, albeit under the

guidelines of each institution and availability of letter writers.

Conditions

Living facilities in California State Prison (July 19, 2006)

The non-governmental organization Human Rights Watch

claims that prisoners and detainees face "abusive, degrading and

dangerous" conditions within local, state and federal facilities,

including those operated by for-profit contractors. The organization also raised concerns with prisoner rape and medical care for inmates. In a survey of 1,788 male inmates in Midwestern prisons by Prison Journal, about 21% responded they had been coerced or pressured into sexual activity during their incarceration, and 7% that they had been raped in their current facility.

In August 2003, a Harper's article by Wil S. Hylton estimated that "somewhere between 20 and 40% of American prisoners are, at this very moment, infected with hepatitis C". Prisons may outsource medical care to private companies such as Correctional Medical Services (now Corizon) that, according to Hylton's research, try to minimize the amount of care given to prisoners in order to maximize profits.

After the privatization of healthcare in Arizona's prisons, medical

spending fell by 30 million dollars and staffing was greatly reduced.

Some 50 prisoners died in custody in the first 8 months of 2013,

compared to 37 for the preceding two years combined.

The poor quality of food provided to inmates has become an issue,

as over the last decade corrections officials looking to cut costs have

been outsourcing food services to private, for-profit corporations such

as Aramark, A'Viands Food & Services Management, and ABL Management. A prison riot in Kentucky has been blamed on the low quality of food Aramark provided to inmates. A 2017 study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

found that because of lapses in food safety, prison inmates are 6.4

times more likely to contract a food-related illness than the general

population.

Also identified as an issue within the prison system is gang

violence, because many gang members retain their gang identity and

affiliations when imprisoned. Segregation of identified gang members

from the general population of inmates, with different gangs

being housed in separate units often results in the imprisonment of

these gang members with their friends and criminal cohorts. Some feel

this has the effect of turning prisons into "institutions of higher

criminal learning."

Many prisons in the United States are overcrowded. For example,

California's 33 prisons have a total capacity of 100,000, but they hold

170,000 inmates.

Many prisons in California and around the country are forced to turn

old gymnasiums and classrooms into huge bunkhouses for inmates. They do

this by placing hundreds of bunk beds next to one another, in these

gyms, without any type of barriers to keep inmates separated. In

California, the inadequate security engendered by this situation,

coupled with insufficient staffing levels, have led to increased

violence and a prison health system that causes one death a week. This

situation has led the courts to order California to release 27% of the

current prison population, citing the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. The three-judge court considering requests by the Plata v. Schwarzenegger and Coleman v. Schwarzenegger courts found California's prisons have become criminogenic as a result of prison overcrowding.

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court case of Cutter v. Wilkinson established that prisons that received federal funds could not deny prisoners accommodations necessary for religious practices.

According to a Supreme Court

ruling issued on May 23, 2011, California — which has the highest

overcrowding rate of any prison system in the country — must alleviate

overcrowding in the state's prisons, reducing the prisoner population by

30,000 over the next two years.

Inmates in a Orleans Parish Prison yard

Solitary confinement is widely used in US prisons,

yet it is underreported by most states, while some don't report it at

all. Isolation of prisoners has been condemned by the UN in 2011 as a

form of torture. At over 80,000 at any given time, the US has more

prisoners confined in isolation than any other country in the world. In

Louisiana, with 843 prisoners per 100,000 citizens, there have been

prisoners, such as the Angola Three, held for as long as forty years in isolation.

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Norway refused to extradite American hashish-smuggler Henry Hendricksen, as they declared that US prisons do not meet their minimum humanitarian standards.

In 2011, some 885 people died while being held in local jails

(not in prisons after being convicted of a crime and sentenced)

throughout the United States. According to federal statistics, roughly 4,400 inmates die in US prisons and jails annually, excluding executions.

As of September 2013, condoms for prisoners are only available in

the U.S. State of Vermont (on September 17, 2013, the California Senate

approved a bill for condom distribution inside the state's prisons, but

the bill was not yet law at the time of approval) and in county jails in San Francisco.

In September 2016, a group of corrections officers at Holman Correctional Facility

have gone on strike over safety concerns and overcrowding. Prisoners

refer to the facility as a "slaughterhouse" as stabbings are a routine

occurrence.

Privatization

Prior to the 1980s, private prisons did not exist in the U.S. During the 1980s, as a result of the War on Drugs by the Reagan Administration, the number of people incarcerated rose. This created a demand for more prison space. The result was the development of privatization and the for-profit prison industry.

A 1998 study was performed using three comparable Louisiana

medium security prisons, two of which were privately run by different

corporations and one of which was publicly run. The data from this study

suggested that the privately run prisons operated more cost-effectively

without sacrificing the safety of inmates and staff. The study

concluded that both privately run prisons had a lower cost per inmate, a

lower rate of critical incidents, a safer environment for employees and

inmates, and a higher proportional rate of inmates who completed basic

education, literacy, and vocational training courses. However, the

publicly run prison outperformed the privately run prisons in areas such

as experiencing fewer escape attempts, controlling substance abuse

through testing, offering a wider range of educational and vocational

courses, and providing a broader range of treatment, recreation, social

services, and rehabilitative services.

According to Marie Gottschalk,

a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania,

studies that claim private prisons are cheaper to run than public

prisons fail to "take into account the fundamental differences between

private and public facilities," and that the prison industry "engages in

a lot of cherry-picking and cost-shifting to maintain the illusion that

the private sector does it better for less." The American Civil Liberties Union

reported in 2013 that numerous studies indicate private jails are

actually filthier, more violent, less accountable, and possibly more

costly than their public counterparts. The ACLU stated that the

for-profit prison industry is "a major contributor to bloated state

budgets and mass incarceration – not a part of any viable solution to

these urgent problems." The primary reason Louisiana is the prison capital of the world is because of the for-profit prison industry. According to The Times-Picayune,

"a majority of Louisiana inmates are housed in for-profit facilities,

which must be supplied with a constant influx of human beings or a

$182 million industry will go bankrupt."

In Mississippi, a 2013 Bloomberg report

stated that assault rates in private facilities were three times higher

on average than in their public counterparts. In 2012, the for-profit Walnut Grove Youth Correctional Facility was the most violent prison in the state with 27 assaults per 100 offenders. A federal lawsuit filed by the ACLU and the Southern Poverty Law Center on behalf of prisoners at the privately run East Mississippi Correctional Facility

in 2013 claims the conditions there are "hyper-violent," "barbaric" and

"chaotic," with gangs routinely beating and exploiting mentally ill

inmates who are denied medical care by prison staff. A May 2012 riot in the Corrections Corporation of America-run Adams County Correctional Facility,

also in Mississippi, left one corrections officer dead and dozens

injured. Similar riots have occurred in privatized facilities in Idaho,

Oklahoma, New Mexico, Florida, California and Texas.

Tallahatchie County Correctional Facility in Mississippi, operated by Corrections Corporation of America (CCA)

Sociologist John L. Campbell of Dartmouth College claims that private prisons in the U.S. have become "a lucrative business."

Between 1990 and 2000, the number of private facilities grew from five

to 100, operated by nearly 20 private firms. Over the same time period

the stock price of the industry leader, Corrections Corporation of

America (CCA), which rebranded as CoreCivic in 2016 amid increased scrutiny of the private prison industry, climbed from $8 a share to $30. According to journalist Matt Taibbi, major investors in the prison industry include Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Fidelity Investments, General Electric and The Vanguard Group. The aforementioned Bloomberg report also notes that in the past decade the number of inmates in for-profit prisons throughout the U.S. rose 44 percent.

Controversy has surrounded the privatization of prisons with the exposure of the genesis of the landmark Arizona SB 1070 law. This law was written by Arizona State Congressman Russell Pearce and the CCA at a meeting of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) in the Grand Hyatt in Washington, D.C. Both CCA and GEO Group,

the two largest operators of private facilities, have been contributors

to ALEC, which lobbies for policies that would increase incarceration,

such as three-strike laws and "truth-in-sentencing" legislation. In fact, in the early 1990s, when CCA was co-chair of ALEC, it co-sponsored (with the National Rifle Association) the so-called "truth-in-sentencing" and "three-strikes-you're-out" laws.

Truth-in-sentencing called for all violent offenders to serve 85

percent of their sentences before being eligible for release; three

strikes called for mandatory life imprisonment for a third felony

conviction. Some prison officers unions in publicly run facilities such

as California Correctional Peace Officers Association have, in the past, also supported measures such as three-strike laws. Such laws increased the prison population.

In addition to CCA and GEO Group, companies operating in the private prison business include Management and Training Corporation, and Community Education Centers. The GEO Group was formerly known as the Wackenhut Corrections division. It includes the former Correctional Services Corporation and Cornell Companies,

which were purchased by GEO in 2005 and 2010. Such companies often sign

contracts with states obliging them to fill prison beds or reimburse

them for those that go unused.

Private companies which provide services to prisons combine in the American Correctional Association, a 501(c)3 which advocates legislation favorable to the industry. Such private companies comprise what has been termed the prison–industrial complex. An example of this phenomenon would be the Kids for cash scandal, in which two judges in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, Mark Ciavarella and Michael Conahan, were receiving judicial kickbacks for sending youths, convicted of minor crimes, to a privatized, for-profit juvenile facility run by the Mid Atlantic Youth Service Corporation.

The industry is aware of what reduced crime rates could mean to their bottom line. This from the CCA's SEC report in 2010:

Our growth … depends on a number of factors we cannot control, including crime rates …[R]eductions in crime rates … could lead to reductions in arrests, convictions and sentences requiring incarceration at correctional facilities.

Marie Gottschalk claims that while private prison companies and other

economic interests were not the primary drivers of mass incarceration

originally, they do much to sustain it today.

The private prison industry has successfully lobbied for changes that

increase the profit of their employers. They have opposed measures that

would bring reduced sentencing or shorter prison terms. The private prison industry has been accused of being at least partly responsible for America's high rates of incarceration.

According to The Corrections Yearbook, 2000, the average annual

starting salary for public corrections officers was $23,002, compared to

$17,628 for private prison guards. The poor pay is a likely factor in

the high turnover rate in private prisons, at 52.2 percent compared to

16 percent in public facilities.

In September 2015, Senator Bernie Sanders introduced the "Justice Is Not for Sale" Act,

which would prohibit the United States government at federal, state and

local levels from contracting with private firms to provide and/or

operate detention facilities within two years.

An August 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Justice asserts

that privately operated federal facilities are less safe, less secure

and more punitive than other federal prisons. Shortly after this report was published, the DoJ announced it will stop using private prisons. On February 23, the DOJ under Attorney General Jeff Sessions

overturned the ban on using private prisons. According to Sessions,

"the (Obama administration) memorandum changed long-standing policy and

practice, and impaired the bureau's ability to meet the future needs of

the federal correctional system. Therefore, I direct the bureau to

return to its previous approach." The private prison industry has been booming under the Trump Administration.

Additionally, both CCA and GEO Group have been expanding into the

immigrant detention market. Although the combined revenues of CCA and

GEO Group were about $4 billion in 2017 from private prison contracts,

their number one customer was ICE.

Employment

About 18% of eligible prisoners held in federal prisons are employed by UNICOR and are paid less than $1.25 an hour. Prisons have gradually become a source of low-wage labor for corporations seeking to outsource work to inmates. Corporations that utilize prison labor include Walmart, Eddie Bauer, Victoria's Secret, Microsoft, Starbucks, McDonald's, Nintendo, Chevron Corporation, Bank of America, Koch Industries, Boeing and Costco Wholesale.

It is estimated that 1 in 9 state government employees works in corrections.

As the overall U.S. prison population declined in 2010, states are

closing prisons. For instance, Virginia has removed 11 prisons since

2009. Like other small towns, Boydton in Virginia has to contend with

unemployment woes resulting from the closure of the Mecklenburg Correctional Center.

In September 2016, large, coordinated prison strikes took place

in 11 states, with inmates claiming they are subjected to poor sanitary

conditions and jobs that amount to forced labor and modern day slavery. Organizers, which include the Industrial Workers of the World labor union, assert it is the largest prison strike in U.S. history.

Starting August 21, 2018, another prison strike, sponsored by Jailhouse Lawyers Speak and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee,

took place in 17 states from coast to coast to protest what inmates

regard as unfair treatment by the criminal justice system. In

particular, inmates objected to being excluded from the 13th amendment

which forces them to work for pennies a day, a condition they assert is

tantamount to "modern-day slavery." The strike was the result of a call

to action after a deadly riot occurred at Lee Correctional Institution in April of that year, which was sparked by neglect and inhumane living conditions.

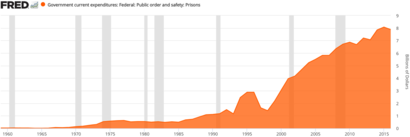

Cost

U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Not adjusted for inflation. To view the inflation-adjusted data, see chart.

Federal prison yearly cost

Judicial, police, and corrections costs totaled $212 billion in 2011 according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In 2007, around $74 billion was spent on corrections according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

In 2014, among facilities operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons,

the average cost of incarceration for federal inmates in fiscal year

2014 was $30,619.85. The average annual cost to confine an inmate in a

residential re-entry center was $28,999.25.

State prisons averaged $31,286 per inmate in 2010 according to a Vera Institute of Justice study. It ranged from $14,603 in Kentucky to $60,076 in New York.

In California in 2008, it cost the state an average of $47,102 a

year to incarcerate an inmate in a state prison. From 2001 to 2009, the

average annual cost increased by about $19,500.

Housing the approximately 500,000 people in jail in the US awaiting trial who cannot afford bail costs $9 billion a year. Most jail inmates are petty, nonviolent offenders. Twenty years ago most nonviolent defendants were released on their own recognizance (trusted to show up at trial). Now most are given bail, and most pay a bail bondsman to afford it. 62% of local jail inmates are awaiting trial.

Bondsmen have lobbied to cut back local pretrial programs from Texas to California, pushed for legislation in four states limiting pretrial's resources, and lobbied Congress so that they won't have to pay the bond if the defendant commits a new crime. Behind them, the bondsmen have powerful special interest group and millions of dollars. Pretrial release agencies have a smattering of public employees and the remnants of their once-thriving programs.

— National Public Radio, January 22, 2010.

To ease jail overcrowding over 10 counties every year consider building new jails. As an example Lubbock County, Texas has decided to build a $110 million megajail to ease jail overcrowding. Jail costs an average of $60 a day nationally. In Broward County, Florida

supervised pretrial release costs about $7 a day per person while jail

costs $115 a day. The jail system costs a quarter of every county tax

dollar in Broward County, and is the single largest expense to the

county taxpayer.

The National Association of State Budget Officers

reports: "In fiscal 2009, corrections spending represented 3.4 percent

of total state spending and 7.2 percent of general fund spending." They

also report: "Some states exclude certain items when reporting

corrections expenditures. Twenty-one states wholly or partially excluded

juvenile delinquency counseling from their corrections figures and

fifteen states wholly or partially excluded spending on juvenile

institutions. Seventeen states wholly or partially excluded spending on

drug abuse rehabilitation centers and forty-one states wholly or

partially excluded spending on institutions for the criminally insane.

Twenty-two states wholly or partially excluded aid to local governments

for jails. For details, see Table 36."

As of 2007, the cost of medical care for inmates was growing by 10 percent annually.

According to a 2016 study by researchers at Washington University in St. Louis,

the true cost of incarceration exceeds $1 trillion, with half of that

falling on the families, children and communities of those incarcerated.

According to a 2016 analysis of federal data by the U.S.

Education Department, state and local spending on incarceration has

grown three times as much as spending on public education since 1980.

Effects of incarceration

Property crime rates in the United States per 100,000 population beginning in 1960 (Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics)

Violent crime rates by gender 1973–2003

Effects on crime rates

Increasing incarceration has a negative effect on crime, but this effect becomes smaller as the incarceration rate increases.

Higher rates of prison admissions increase crime rates, whereas

moderate rates of prison admissions decrease crime. The rate of prisoner

releases in a given year in a community is also positively related to

that community's crime rate the following year.

A 2010 study of panel data

from 1978 to 2003 indicated that the crime-reducing effects of

increasing incarceration are totally offset by the crime-increasing

effects of prisoner re-entry.

Social effects

Within

three years of being released, 67% of ex-prisoners re-offend and 52%

are re-incarcerated, according to a study published in 1994.

The rate of recidivism is so high in the United States that most

inmates who enter the system are likely to reenter within a year of

their release.

Former inmate Wenona Thompson argues "I realized that I became part of a

cycle, a system, that looked forward to seeing me there. And I was

aware that...I would be one of those people who fill up their prisons".

In 1995, the government allocated $5.1 billion for new prison

space. Every $100 million spent in construction costs $53 million per

year in finance and operational costs over the next three decades. Taxpayers spend $60 billion a year for prisons. In 2005, it cost an average of $23,876 a year to house a prisoner. It takes about $30,000 per year per person to provide drug rehabilitation

treatment to inmates. By contrast, the cost of drug rehabilitation

treatment outside of a prison costs about $8,000 per year per person.

The effects of such high incarceration rates are also shown in

other ways. For example, a person who has been recently released from

prison is ineligible for welfare in most states. They are not eligible

for subsidized housing, and for Section 8 they have to wait two years

before they can apply. In addition to finding housing, they also have to

find employment, but this can be difficult as employers often check for

a potential employees Criminal record.

Essentially, a person who has been recently released from prison comes

into a society that is not prepared structurally or emotionally to

welcome them back.

In The New Jim Crow in 2011, legal scholar and advocate Michelle Alexander

contended that the U.S. incarceration system worked to bar black men

from voting. She wrote "there are more African Americans under

correctional control -- in prison or jail, on probation or parole --

than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began". Alexander's work has drawn increased attention through 2011 and into 2013.

Yale Law Professor, and opponent of mass incarceration James Forman Jr. has countered that 1) African Americans, as represented by such cities as the District of Columbia, have generally supported tough on crime policies.

2) There appears to be a connection between drugs and violent crimes,

the discussion of which, he says, New Jim Crow theorists have avoided.

3) New theorists have overlooked class as a factor in incarceration.

Blacks with advanced degrees have fewer convictions. Blacks without

advanced education have more.

Effects of parental incarceration on children

Incarceration

of an individual does not have a singular effect: it affects those in

the individual's tight-knit circle as well. For every mother that is

incarcerated in the United States there are about another ten people

(children, grandparents, community, etc.) that are directly affected. Moreover, more than 2.7 million children in the United States have an incarcerated parent. That translates to one out of every 27 children in the United States having an incarcerated parent. Approximately 80 percent of women who go to jail each year are mothers. This

ripple effect on the individual's family amplifies the debilitating

effect that entails arresting individuals. Given the general

vulnerability and naivete of children, it is important to understand how

such a traumatic event adversely affects children. The effects of a

parent’s incarceration on their children have been found as early as

three years old. Local and state governments in the United States have recognized these harmful effects and have attempted to address them through public policy solutions.

Health and behavioral effects

The

effects of an early traumatic experience of a child can be categorized

into health effects and behavioral externalizations. Many studies have

searched for a correlation between witnessing a parent's arrest and a

wide variety of physiological issues. For example, Lee et al. showed

significant correlation between high cholesterol, Migraine, and HIV/AIDS diagnosis to children with a parental incarceration.

Even while adjusting for various socioeconomic and racial factors,

children with an incarcerated parent have a significantly higher chance

of developing a wide variety of physical problems such as Obesity, asthma, and developmental delays.

The current literature acknowledges that there are a variety of poor

health outcomes as a direct result of being separated from a parent by law enforcement.

It is hypothesized that the chronic stress that results directly from

the uncertainty of the parent's legal status is the primary influence

for the extensive list of acute and chronic conditions that could

develop later in life.

In addition to the chronic stress, the immediate instability in a

child's life deprives them of certain essentials e.g. money for food,

parental love that are compulsory for leading a healthy life. Though

most of the adverse effects that result from parental incarceration are

regardless of whether the mother or father was arrested, some

differences have been discovered. For example, males whose father have

been incarcerated display more behavioral issues than any other

combination of parent/child.

There has also been a substantial effort to understand how this

traumatic experience manifests in the child's mental health and to

identify externalizations that may be helpful for a diagnosis. The most

prominent mental health outcomes in these children are Anxiety disorder, Depression (mood), and Posttraumatic stress disorder(PTSD). These problems worsen in a typical positive feedback

loop without the presence of a parental figure. Given the chronic

nature of these diseases, they can be detected and observed at distinct

points in a child's development, allowing for ample research. Murray et

al. have been able to isolate the cause of the expression of Anti-social behaviours specific to the parental incarceration.

In a specific case study in Boston by Sack, within two months of the

father being arrested, the adolescent boy in the family developed severe

aggressive and antisocial behaviors.

This observation is not unique; Sack and other researchers have

noticed an immediate and strong reaction to sudden departures from

family structure norms. These behavioral externalizations are most

evident at school when the child interacts with peers and adults. This

behavior leads to punishment and less focus on education, which has

obvious consequences for future educational and career prospects.

In addition to externalizing undesirable behaviors, children of

incarcerated parents are more likely to be incarcerated compared to

those without incarcerated parents.

More formally, transmission of severe emotional strain on a parent

negatively impacts the children by disrupting the home environment.

Societal stigma against individuals, specifically parents, who are

incarcerated is passed down to their children. The children find this

stigma to be overwhelming and it negatively impacts their short- and

long-term prospects.

Policy solutions

There are four main phases that can be distinguished in the process of arresting a parent: arrest, sentencing,

incarceration, and re-entry. Re-entry is not relevant if a parent is

not arrested for other crimes. During each of these phases, solutions

can be implemented that mitigate the harm placed on the children during

the process. While their parents are away, children rely on other

caretakers (family or friends) to satisfy their basic need. Solutions

for the children of incarcerated parents have identified caretakers as a

focal point for successful intervention.

Arrest Phase

Forced home entry is a primary stressor for children in a residence.

One in five children witness their parent arrested by authorities,

and a study interviewing 30 children reported that the children

experienced Flashbulb Memories and Nightmares associated with the day their parent was arrested.

These single, adverse moments have long-reaching effects and

policymakers around the country have attempted to ameliorate the

situation. For example, the city of San Francisco

in 2005 implemented training policies for its police officers with the

goal of making them more cognizant of the familial situation before

entering the home. The guidelines go a step further and stipulate that

if no information is available before the arrest, that officers ask the

suspect about the possibility of any children in the house. San Francisco is not alone: New Mexico passed a law in 2009 advocating for child safety during parental arrest and California provides funding to agencies to train personnel how to appropriately conduct an arrest in the presence of family members.

Extending past the state level, the Department of Justice has provided

guidelines for police officers around the country to better accommodate

for children in difficult family situations.

Sentencing Phase

During

the sentencing phase, the judge is the primary authority in determine

if the appropriate punishment, if any. Consideration of the sentencing

effects on the defendant’s children could help with the preservation of

the parent-child relationship. In a law passed in 2014, Oklahoma

requires judges to inquire if convicted individuals are single

custodial parents, and if so, authorize the mobility of important

resources so the child’s transition to different circumstances is

monitored.

The distance that the jail or prison is from the arrested individual’s

home is a contributing factor to the parent-child relationship. Allowing

a parent to serve their sentence closer to their residence will allow

for easier visitation and a healthier relationship. Recognizing this,

the New York Senate passed a bill in 2015 that would ensure convicted

individuals be jailed in the nearest facility.

Incarceration Phase

While

serving a sentence, measures have been put in place to allow parents to

exercise their duty as role models and caretakers. The state of New York (state) allows newborns to be with their mothers for up to one year.

Studies have shown that parental, specifically maternal, presence

during a newborn’s early development are crucial to both physical and

cognitive development. Ohio law requires nursery support for pregnant inmates in its facilities.

California also has a stake in the support of incarcerated parents,

too, through its requirement that women in jail with children be

transferred to a community facility that can provide pediatric care.

These regulations are supported by the research on early child

development that argue it is imperative that infants and young children

are with a parental figure, preferably the mother, to ensure proper

development.

This approach received support at the federal level when then-Deputy

Attorney General Sally Yates instituted several family-friendly

measures, for certain facilities, including: improving infrastructure

for video conferencing and informing inmates on how to contact their

children if they were placed in the foster care system, among other

improvements.

Re-entry Phase

The

last phase of the incarceration process is re-entry back into the

community, but more importantly, back into the family structure. Though

the time away is painful for the family, it does not always welcome back

the previously incarcerated individual with open arms.

Not only is the transition into the family difficult, but also into

society as they are faced with establishing secure housing, insurance,

and a new job.

As such, policymakers find it necessary to ease the transition of an

incarcerated individual to the pre-arrest situation. Of the four

outlined phases, re-entry is the least emphasized from a public policy

perspective. This is not to say it is the least important, however, as

there are concerns that time in a correctional facility can deteriorate

the caretaking ability of some prisoners. As a result, Oklahoma has

taken measurable strides by providing parents with the tools they need

to re-enter their families, including classes on parenting skills.

Caretakers

Grandmothers are a common caregiver of children with an incarcerated parent

Though the effects on caregivers of these children vary based on

factors such as the relationship to the prisoner and his or her support

system, it is well-known that it is a financial and emotional burden to

take care of a child. In addition to taking care of the their nuclear family,

caregivers are now responsible for another individual who requires

attention and resources to flourish. Depending on the relationship to

the caregiver, the transition to a new household may not be easy for the

child. The rationale behind targeting caregivers for intervention

policies is to ensure the new environment for the children is healthy

and productive. The federal government funds states to provide

counseling to caretaking family members to alleviate some of the

associated emotional burden. A more comprehensive program from Washington (state)

employs "kinship navigators" to address caretakers' needs with

initiatives such as parental classes and connections to legal services.

Effects on employment

Felony

records greatly influence the chances of people finding employment.

Many employers seem to use criminal history as a screening mechanism

without attempting to probe deeper.

They are often more interested in incarceration as a measure of

employability and trustworthiness instead of its relation to any

specific job. People who have felony records have a harder time finding a job.

The psychological effects of incarceration can also impede an

ex-felon's search for employment. Prison can cause social anxiety,

distrust, and other psychological issues that negatively affect a

person's reintegration into an employment setting. Men who are unemployed are more likely to participate in crime which leads to there being a 67% chance of ex-felons being charged again.

In 2008, the difficulties male ex-felons in the United States had

finding employment lead to approximately a 1.6% decrease in the

employment rate alone. This is a loss of between $57 and $65 billion of

output to the US economy.

Although incarceration in general has a huge effect on

employment, the effects become even more pronounced when looking at

race. Devah Pager performed a study in 2003 and found that white males

with no criminal record had a 34% chance of callback compared to 17% for

white males with a criminal record. Black males with no criminal record

were called back at a rate of 14% while the rate dropped to 5% for

those with a criminal record. Black men with no criminal background have