Puritans were dissatisfied with the limited extent of the English Reformation

and with the Church of England's toleration of certain practices

associated with the Roman Catholic Church. They formed and identified

with various religious groups advocating greater purity of worship and doctrine, as well as personal and corporate piety. Puritans adopted a Reformed theology

and, in that sense, were Calvinists (as were many of their earlier

opponents). In church polity, some advocated separation from all other

established Christian denominations in favour of autonomous gathered churches. These separatist and independent strands of Puritanism became prominent in the 1640s, when the supporters of a Presbyterian polity in the Westminster Assembly were unable to forge a new English national church.

By the late 1630s, Puritans were in alliance with the growing commercial world, with the parliamentary opposition to the royal prerogative, and with the Scottish Presbyterians with whom they had much in common. Consequently, they became a major political force in England and came to power as a result of the First English Civil War (1642–1646). Almost all Puritan clergy left the Church of England after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the 1662 Uniformity Act. Many continued to practice their faith in nonconformist denominations, especially in Congregationalist and Presbyterian churches. The nature of the movement in England changed radically, although it retained its character for a much longer period in New England.

Puritanism was never a formally defined religious division within Protestantism, and the term Puritan itself was rarely used after the turn of the 18th century. Some Puritan ideals, including the formal rejection of Roman Catholicism, were incorporated into the doctrines of the Church of England; others were absorbed into the many Protestant denominations that emerged in the late 17th and early 18th centuries in America and Britain. The Congregational churches, widely considered to be a part of the Reformed tradition, are descended from the Puritans. Moreover, Puritan beliefs are enshrined in the Savoy Declaration, the confession of faith held by the Congregationalist churches.

By the late 1630s, Puritans were in alliance with the growing commercial world, with the parliamentary opposition to the royal prerogative, and with the Scottish Presbyterians with whom they had much in common. Consequently, they became a major political force in England and came to power as a result of the First English Civil War (1642–1646). Almost all Puritan clergy left the Church of England after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the 1662 Uniformity Act. Many continued to practice their faith in nonconformist denominations, especially in Congregationalist and Presbyterian churches. The nature of the movement in England changed radically, although it retained its character for a much longer period in New England.

Puritanism was never a formally defined religious division within Protestantism, and the term Puritan itself was rarely used after the turn of the 18th century. Some Puritan ideals, including the formal rejection of Roman Catholicism, were incorporated into the doctrines of the Church of England; others were absorbed into the many Protestant denominations that emerged in the late 17th and early 18th centuries in America and Britain. The Congregational churches, widely considered to be a part of the Reformed tradition, are descended from the Puritans. Moreover, Puritan beliefs are enshrined in the Savoy Declaration, the confession of faith held by the Congregationalist churches.

Terminology

Gallery of famous 17th-century Puritan theologians: Thomas Gouge, William Bridge, Thomas Manton, John Flavel, Richard Sibbes, Stephen Charnock, William Bates, John Owen, John Howe and Richard Baxter

In the 17th century, the word Puritan was a term applied not to just one group but to many. Historians still debate a precise definition of Puritanism. Originally, Puritan was a pejorative term characterizing certain Protestant groups as extremist. Thomas Fuller, in his Church History, dates the first use of the word to 1564. Archbishop Matthew Parker of that time used it and precisian with a sense similar to the modern stickler.

Puritans, then, were distinguished for being "more intensely protestant

than their protestant neighbors or even the Church of England".

"Non-separating Puritans" were dissatisfied with the Reformation of the Church of England

but remained within it, advocating for further reform; they disagreed

among themselves about how much further reformation was possible or even

necessary. "Separatists", or "separating Puritans", thought the Church of England was so corrupt that true Christians should separate from it altogether. In its widest historical sense, the term Puritan includes both groups.

Puritans should not be confused with more radical Protestant groups of the 16th and 17th centuries, such as Quakers, Seekers, and Familists who believed that individuals could be directly guided by the Holy Spirit and prioritized direct revelation over the Bible.

In current English, puritan often means "against pleasure". In such usage, hedonism and puritanism are antonyms. In fact, Puritans embraced sexuality but placed it in the context of marriage. Peter Gay

writes of the Puritans' standard reputation for "dour prudery" as a

"misreading that went unquestioned in the nineteenth century",

commenting how unpuritanical they were in favour of married sexuality,

and in opposition to the Catholic veneration of virginity, citing Edward Taylor and John Cotton. One Puritan settlement in western Massachusetts banished a husband because he refused to fulfill his sexual duties to his wife.

History

Puritanism has a historical importance over a period of a century,

followed by fifty years of development in New England. It changed

character and emphasis almost decade-by-decade over that time.

Elizabethan Puritanism

Elizabethan Puritanism contended with the Elizabethan religious settlement, with little to show for it. The Lambeth Articles of 1595, a high-water mark for Calvinism within the Church of England, failed to receive royal approval.

Jacobean Puritanism

The accession of James I to the English throne brought the Millenary Petition, a Puritan manifesto of 1603 for reform of the English church, but James wanted a religious settlement along different lines. He called the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, and heard the teachings of four prominent Puritan leaders, including Laurence Chaderton,

but largely sided with his bishops. He was well informed on theological

matters by his education and Scottish upbringing, and he dealt shortly

with the peevish legacy of Elizabethan Puritanism, pursuing an eirenic religious policy, in which he was arbiter.

Many of James's episcopal appointments were Calvinists, notably James Montague, who was an influential courtier. Puritans still opposed much of the Roman Catholic summation in the Church of England, notably the Book of Common Prayer

but also the use of non-secular vestments (cap and gown) during

services, the sign of the Cross in baptism, and kneeling to receive Holy

Communion.

Some of the bishops under both Elizabeth and James tried to suppress

Puritanism, though other bishops were more tolerant and, in many places,

individual ministers were able to omit disliked portions of the Book of Common Prayer.

The Puritan movement of Jacobean times became distinctive by

adaptation and compromise, with the emergence of "semi-separatism",

"moderate puritanism", the writings of William Bradshaw (who adopted the term "Puritan" for himself), and the beginnings of Congregationalism.

Most Puritans of this period were non-separating and remained within

the Church of England; Separatists who left the Church of England

altogether were numerically much fewer.

Fragmentation and political failure

The Westminster Assembly, which saw disputes on Church polity in England (Victorian history painting by John Rogers Herbert).

The Puritan movement in England was riven over decades by emigration

and inconsistent interpretations of Scripture, as well as some political

differences that surfaced at that time. The Fifth Monarchy Men, a radical millenarian wing of Puritanism, aided by strident, popular clergy like Vavasor Powell, agitated from the right wing of the movement, even as sectarian groups like the Ranters, Levellers, and Quakers pulled from the left.

The fragmentation created a collapse of the centre and, ultimately,

sealed a political failure, while depositing an enduring spiritual

legacy that would remain and grow in English-speaking Christianity.

The Westminster Assembly was called in 1643, assembling clergy of the Church of England. The Assembly was able to agree to the Westminster Confession of Faith doctrinally, a consistent Reformed theological position. The Directory of Public Worship was made official in 1645, and the larger framework (now called the Westminster Standards) was adopted by the Church of Scotland. In England, the Standards were contested by Independents up to 1660.

The Westminster Divines, on the other hand, were divided over questions of church polity and split into factions supporting a reformed episcopacy, presbyterianism, congregationalism, and Erastianism. The membership of the Assembly was heavily weighted towards the Presbyterians, but Oliver Cromwell was a Puritan and an independent Congregationalist separatist who imposed his doctrines upon them. The Church of England of the Interregnum (1649–60)

was run along Presbyterian lines but never became a national

Presbyterian church, such as existed in Scotland, and England was not

the theocratic state which leading Puritans had called for as "godly

rule".

Great Ejection and Dissenters

At the time of the English Restoration in 1660, the Savoy Conference was called to determine a new religious settlement for England and Wales. Under the Act of Uniformity 1662, the Church of England was restored to its pre-Civil War constitution with only minor changes, and the Puritans found themselves sidelined. A traditional estimate of historian Calamy is that around 2,400 Puritan clergy left the Church in the "Great Ejection" of 1662. At this point, the term "Dissenter" came to include "Puritan", but more accurately described those (clergy or lay) who "dissented" from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

The Dissenters divided themselves from all Christians in the

Church of England and established their own separatist congregations in

the 1660s and 1670s. An estimated 1,800 of the ejected clergy continued

in some fashion as ministers of religion, according to Richard Baxter. The government initially attempted to suppress these schismatic organisations by using the Clarendon Code.

There followed a period in which schemes of "comprehension" were

proposed, under which Presbyterians could be brought back into the

Church of England, but nothing resulted from them. The Whigs

opposed the court religious policies and argued that the Dissenters

should be allowed to worship separately from the established Church, and

this position ultimately prevailed when the Toleration Act was passed in the wake of the Glorious Revolution in 1689. This permitted the licensing of Dissenting ministers and the building of chapels. The term "Nonconformist" generally replaced the term "Dissenter" from the middle of the 18th century.

Puritans in North America

Interior of the Old Ship Church, a Puritan meetinghouse in Hingham, Massachusetts. Puritans were Calvinists,

so their churches were unadorned and plain. It is the oldest building

in continuous ecclesiastical use in America and today serves a Unitarian Universalist congregation.

Some Puritans left for New England, particularly in the years after 1630, supporting the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

and other settlements among the northern colonies. The large-scale

Puritan immigration to New England ceased by 1641, with around 21,000

having moved across the Atlantic. This English-speaking population in

America did not all consist of original colonists, since many returned

to England shortly after arriving on the continent, but it produced more

than 16 million descendants.

This so-called "Great Migration" is not so named because of sheer

numbers, which were much less than the number of English citizens who

immigrated to Virginia and the Caribbean during this time.

The rapid growth of the New England colonies (around 700,000 by 1790)

was almost entirely due to the high birth rate and lower death rate per

year.

Puritan hegemony lasted for at least a century. That century can be broken down into three parts: the generation of John Cotton and Richard Mather,

1630–62 from the founding to the Restoration, years of virtual

independence and nearly autonomous development; the generation of Increase Mather,

1662–89 from the Restoration and the Halfway Covenant to the Glorious

Revolution, years of struggle with the British crown; and the generation

of Cotton Mather, 1689–1728 from the overthrow of Edmund Andros (in which Cotton Mather played a part) and the new charter, mediated by Increase Mather, to the death of Cotton Mather.

Beliefs

Calvinism

Puritanism broadly refers to a diverse religious reform movement in Britain committed to the continental Reformed tradition. While Puritans did not agree on all doctrinal points, most shared similar views on the nature of God, human sinfulness, and the relationship between God and mankind. They believed that all of their beliefs should be based on the Bible, which they considered to be divinely inspired.

The concept of covenant was extremely important to Puritans, and covenant theology was central to their beliefs. With roots in the writings of Reformed theologians John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger, covenant theology was further developed by Puritan theologians Dudley Fenner, William Perkins, John Preston, Richard Sibbes, William Ames and, most fully by Ames's Dutch student, Johannes Cocceius. Covenant theology asserts that when God created Adam and Eve he promised them eternal life in return for perfect obedience; this promise was termed the covenant of works. After the fall of man, human nature was corrupted by original sin and unable to fulfill the covenant of works, since each person inevitably violated God's law as expressed in the Ten Commandments. As sinners, every person deserved damnation.

Puritans shared with other Calvinists a belief in double predestination, that some people (the elect) were destined by God to receive grace and salvation while others were destined for Hell. No one, however, could merit salvation. According to covenant theology, Christ's sacrifice on the cross made possible the covenant of grace, by which those selected by God could be saved. Puritans believed in unconditional election and irresistible grace—God's grace was given freely without condition to the elect and could not be refused.

Conversion

Covenant

theology made individual salvation deeply personal. It held that God's

predestination was not "impersonal and mechanical" but was a "covenant

of grace" that one entered into by faith.

Therefore, being a Christian could never be reduced to simple

"intellectual acknowledgment" of the truth of Christianity. Puritans

agreed "that the effectual call of each elect saint of God would always come as an individuated personal encounter with God's promises".

The process by which the elect are brought from spiritual death to spiritual life (regeneration) was described as conversion. Early on, Puritans did not consider a specific conversion experience normative or necessary, but many gained assurance of salvation

from such experiences. Over time, however, Puritan theologians

developed a framework for authentic religious experience based on their

own experiences as well as those of their parishioners. Eventually,

Puritans came to regard a specific conversion experience as an essential

mark of one's election.

The Puritan conversion experience was commonly described as

occurring in discrete phases. It began with a preparatory phase designed

to produce contrition for sin through introspection, Bible study and listening to preaching. This was followed by humiliation,

when the sinner realized that he or she was helpless to break free from

sin and that their good works could never earn forgiveness. It was after reaching this point—the realization that salvation was possible only because of divine mercy—that the person would experience justification, when the righteousness of Christ is imputed

to the elect and their minds and hearts are regenerated. For some

Puritans, this was a dramatic experience and they referred to it as

being born again.

Confirming that such a conversion had actually happened often required prolonged and continual introspection. Historian Perry Miller wrote that the Puritans "liberated men from the treadmill of indulgences and penances, but cast them on the iron couch of introspection". It was expected that conversion would be followed by sanctification—"the progressive growth in the saint's ability to better perceive and seek God's will, and thus to lead a holy life".

Some Puritans attempted to find assurance of their faith by keeping

detailed records of their behavior and looking for the evidence of

salvation in their lives. Puritan clergy wrote many spiritual guides to

help their parishioners pursue personal piety and sanctification. These included Arthur Dent's The Plain Man's Pathway to Heaven (1601), Richard Rogers's Seven Treatises (1603), Henry Scudder's Christian's Daily Walk (1627) and Richard Sibbes's The Bruised Reed and Smoking Flax (1630).

Too much emphasis on one's good works could be criticized for being too close to Arminianism, and too much emphasis on subjective religious experience could be criticized as Antinomianism. Many Puritans relied on both personal religious experience and self-examination to assess their spiritual condition.

Puritanism's experiential piety would be inherited by the evangelical Protestants of the 18th century.

While evangelical views on conversion were heavily influenced by

Puritan theology, the Puritans believed that assurance of one's

salvation was "rare, late and the fruit of struggle in the experience of

believers", whereas evangelicals believed that assurance was normative

for all the truly converted.

Worship and sacraments

The sermon was central to Puritan public worship. The sermon was not

only a means of religious education; Puritans believed it was the most

common way that God prepared a sinner's heart for conversion. Puritans eliminated choral music and musical instruments in their religious services because these were associated with Roman Catholicism; however, settings of the Psalms were considered appropriate. Church organs were commonly damaged or destroyed in the Civil War period, such as when an axe was taken to the organ of Worcester Cathedral in 1642. Puritans taught that there were two sacraments: baptism and the Lord's Supper. They rejected confirmation as unnecessary.

Puritans unanimously rejected the Roman Catholic doctrine of baptismal regeneration, but they disagreed among themselves on the effects of baptism and its relationship to regeneration. Most Puritans practiced infant baptism, but a minority held credobaptist beliefs. Those who baptized infants understood it through the lens of covenant theology, believing that baptism had replaced circumcision as a sign of the covenant and marked a child's admission into the visible church. In "A Discourse on the Nature of Regeneration", Stephen Charnock

distinguished regeneration from "external baptism" writing that baptism

"confers not grace" but rather is a means of conveying the grace of

regeneration only "when the [Holy] Spirit is pleased to operate with

it". Therefore, one cannot assume that baptism produces regeneration.

The Westminster Confession states that the grace of baptism is only

effective for those who are among the elect; however, its effects are

not tied to the moment of baptism but lies dormant until one experiences

conversion later in life.

Puritans rejected both Roman Catholic (transubstantiation) and Lutheran (sacramental union) teachings that Christ is physically present in the bread and wine

of the Lord's Supper. Instead, Puritans embraced the Reformed doctrine

of real spiritual presence, believing that in the Lord's Supper the

faithful receive Christ spiritually. In agreement with Thomas Cranmer,

the Puritans stressed "that Christ comes down to us in the sacrament by

His Word and Spirit, offering Himself as our spiritual food and drink".

Ecclesiology

Polemical popular print with a Catalogue of Sects, 1647.

While the Puritans were united in their goal of furthering the English Reformation, they were always divided over issues of ecclesiology and church polity,

specifically questions relating to the manner of organizing

congregations, how individual congregations should relate with one

another and whether established national churches were scriptural. On these questions, Puritans divided between supporters of episcopal polity, presbyterian polity and congregational polity.

The episcopalians (known as the prelatical party) were conservatives who supported retaining bishops if those leaders supported reform and agreed to share power with local churches. They also supported the idea of having a Book of Common Prayer,

but they were against demanding strict conformity or having too much

ceremony. In addition, these Puritans called for a renewal of preaching,

pastoral care and Christian discipline within the Church of England.

Like the episcopalians, the presbyterians agreed that there should be a national church but one structured on the model of the Church of Scotland. They wanted to replace bishops with a system of elective and representative governing bodies of clergy and laity (local sessions, presbyteries, synods, and ultimately a national general assembly). During the Interregnum, the presbyterians had limited success at reorganizing the Church of England. The Westminster Assembly proposed the creation of a presbyterian system, but the Long Parliament left implementation to local authorities. As a result, the Church of England never developed a complete presbyterian hierarchy.

Congregationalists or Independents believed in the autonomy of

the local church, which ideally would be a congregation of "visible

saints" (meaning those who had experienced conversion). Members would be required to abide by a church covenant,

in which they "pledged to join in the proper worship of God and to

nourish each other in the search for further religious truth".

Such churches were regarded as complete within themselves, with full

authority to determine their own membership, administer their own

discipline and ordain their own ministers. Furthermore, the sacraments

would only be administered to those in the church covenant.

Most congregational Puritans remained within the Church of England, hoping to reform it according to their own views. The New England Congregationalists

were also adamant that they were not separating from the Church of

England. However, some Puritans equated the Church of England with the

Roman Catholic Church, and therefore considered it no Christian church

at all. These groups, such as the Brownists, would split from the established church and become known as Separatists. Other Separatists embraced more radical positions on separation of church and state and believer's baptism, becoming early Baptists.

Family life

The Snake in the Grass or Satan Transform'd to an Angel of Light, title page engraved by Richard Gaywood, ca. 1660

Based on Biblical portrayals of Adam and Eve, Puritans believed that

marriage was rooted in procreation, love, and, most importantly,

salvation.

Husbands were the spiritual heads of the household, while women were to

demonstrate religious piety and obedience under male authority.

Furthermore, marriage represented not only the relationship between

husband and wife, but also the relationship between spouses and God.

Puritan husbands commanded authority through family direction and

prayer. The female relationship to her husband and to God was marked by

submissiveness and humility.

Thomas Gataker describes Puritan marriage as:

... together for a time as copartners in grace here, [that] they may reigne together forever as coheires in glory hereafter.

The paradox created by female inferiority in the public sphere and

the spiritual equality of men and women in marriage, then, gave way to

the informal authority of women concerning matters of the home and

childrearing.

With the consent of their husbands, wives made important decisions

concerning the labour of their children, property, and the management of

inns and taverns owned by their husbands.

Pious Puritan mothers laboured for their children's righteousness and

salvation, connecting women directly to matters of religion and

morality. In her poem titled "In Reference to her Children", poet Anne Bradstreet reflects on her role as a mother:

I had eight birds hatched in one nest; Four cocks there were, and hens the rest. I nursed them up with pain and care, Nor cost nor labour I did spare.

Bradstreet alludes to the temporality

of motherhood by comparing her children to a flock of birds on the

precipice of leaving home. While Puritans praised the obedience of young

children, they also believed that, by separating children from their

mothers at adolescence, children could better sustain a superior

relationship with God.

A child could only be redeemed through religious education and

obedience. Girls carried the additional burden of Eve's corruption and

were catechised

separately from boys at adolescence. Boys' education prepared them for

vocations and leadership roles, while girls were educated for domestic

and religious purposes. The pinnacle of achievement for children in

Puritan society, however, occurred with the conversion process.

Puritans viewed the relationship between master and servant

similarly to that of parent and child. Just as parents were expected to

uphold Puritan religious values in the home, masters assumed the

parental responsibility of housing and educating young servants. Older

servants also dwelt with masters and were cared for in the event of

illness or injury. African-American and Indian servants were likely

excluded from such benefits.

Demonology and witch hunts

Like most Christians in the early modern period, Puritans believed in the active existence of the devil and demons as evil forces that could possess and cause harm to men and women. There was also widespread belief in witchcraft

and witches—persons in league with the devil. "Unexplained phenomena

such as the death of livestock, human disease, and hideous fits suffered

by young and old" might all be blamed on the agency of the devil or a

witch.

Puritan pastors undertook exorcisms for demonic possession in some high-profile cases. Exorcist John Darrell was supported by Arthur Hildersham in the case of Thomas Darling. Samuel Harsnett,

a skeptic on witchcraft and possession, attacked Darrell. However,

Harsnett was in the minority, and many clergy, not only Puritans,

believed in witchcraft and possession.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of people throughout

Europe were accused of being witches and executed. In England and

America, Puritans engaged in witch hunts as well. In the 1640s, Matthew Hopkins,

the self-proclaimed "Witchfinder General", was responsible for accusing

over two hundred people of witchcraft, mainly in East Anglia. In New

England, few people were accused and convicted of witchcraft before

1692; there were at most sixteen convictions.

The Salem witch trials

of 1692 had a lasting impact on the historical reputation of New

England Puritans. Though this witch hunt occurred after Puritans lost

political control of the Massachusetts colony,

Puritans instigated the judicial proceedings against the accused and

comprised the members of the court that convicted and sentenced the

accused. By the time Governor William Phips ended the trials, fourteen women and five men had been hanged as witches.

Millennialism

Puritan millennialism has been placed in the broader context of European Reformed beliefs about the millennium and interpretation of biblical prophecy, for which representative figures of the period were Johannes Piscator, Thomas Brightman, Joseph Mede, Johannes Heinrich Alsted, and John Amos Comenius. Like most English Protestants of the time, Puritans based their eschatological views on an historicist interpretation of the Book of Revelation and the Book of Daniel. Protestant theologians identified the sequential phases the world must pass through before the Last Judgment

could occur and tended to place their own time period near the end. It

was expected that tribulation and persecution would increase but

eventually the church's enemies—the Antichrist (identified with the Roman Catholic Church) and the Ottoman Empire—would be defeated. Based on Revelation 20,

it was believed that a thousand year period (the millennium) would

occur, during which the saints would rule with Christ on earth.

In contrast to other Protestants who tended to view eschatology

as an explanation for "God's remote plans for the world and man",

Puritans understood it to describe "the cosmic environment in which the

regenerate soldier of Christ was now to do battle against the power of

sin".

On a personal level, eschatology was related to sanctification,

assurance of salvation, and the conversion experience. On a larger

level, eschatology was the lens through which events such as the English

Civil War and the Thirty Years' War

were interpreted. There was also an optimistic aspect to Puritan

millennianism; Puritans anticipated a future worldwide religious revival

before the Second Coming of Christ. Another departure from other Protestants was the widespread belief among Puritans that the conversion of the Jews to Christianity was an important sign of the apocalypse.

David Brady describes a "lull before the storm"

in the early 17th century, in which "reasonably restrained and

systematic" Protestant exegesis of the Book of Revelation was seen with

Brightman, Mede, and Hugh Broughton, after which "apocalyptic literature became too easily debased" as it became more populist and less scholarly. William Lamont argues that, within the church, the Elizabethan millennial beliefs of John Foxe

became sidelined, with Puritans adopting instead the "centrifugal"

doctrines of Thomas Brightman, while the Laudians replaced the

"centripetal" attitude of Foxe to the "Christian Emperor" by the

national and episcopal Church closer to home, with its royal head, as

leading the Protestant world iure divino (by divine right).

Viggo Norskov Olsen writes that Mede "broke fully away from the

Augustinian-Foxian tradition, and is the link between Brightman and the premillennialism of the 17th century". The dam broke in 1641 when the traditional retrospective reverence for Thomas Cranmer and other martyred bishops in the Acts and Monuments was displaced by forward-looking attitudes to prophecy among radical Puritans.

Cultural consequences

Some strong religious beliefs common to Puritans had direct impacts

on culture. Puritans believed it was the government's responsibility to

enforce moral standards and ensure true religious worship was

established and maintained.

Education was essential to every person, male and female, so that they

could read the Bible for themselves. However, the Puritans' emphasis on

individual spiritual independence was not always compatible with the

community cohesion that was also a strong ideal. Anne Hutchinson

(1591–1643), the well educated daughter of a teacher, argued with the

established theological orthodoxy, and was forced to leave the colony

with her followers.

Education

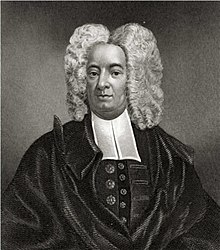

Cotton Mather, influential New England Puritan minister, portrait by Peter Pelham.

At a time when the literacy rate in England was less than 30 percent,

the Puritan leaders of colonial New England believed children should be

educated for both religious and civil reasons, and they worked to

achieve universal literacy.

In 1642, Massachusetts required heads of households to teach their

wives, children and servants basic reading and writing so that they

could read the Bible and understand colonial laws. In 1647, the

government required all towns with 50 or more households to hire a

teacher and towns of 100 or more households to hire a grammar school instructor to prepare promising boys for college. Boys interested in the ministry were often sent to colleges such as Harvard (founded in 1636) or Yale (founded in 1707). Aspiring lawyers or doctors apprenticed to a local practitioner, or in rare cases were sent to England or Scotland.

Puritan scientists

The Merton Thesis is an argument about the nature of early experimental science proposed by Robert K. Merton. Similar to Max Weber's famous claim on the link between the Protestant work ethic and the capitalist economy, Merton argued for a similar positive correlation between the rise of English Puritanism, as well as German Pietism, and early experimental science. As an example, seven of 10 nucleus members of the Royal Society were Puritans. In the year 1663, 62 percent of the members of the Royal Society were similarly identified. The Merton Thesis has resulted in continuous debates.

Behavioral regulations

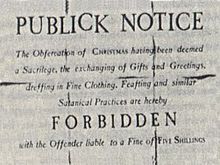

1659 public notice in Boston deeming Christmas illegal

Puritans in both England and New England believed that the state

should protect and promote true religion and that religion should

influence politics and social life. Certain holidays were outlawed when Puritans came to power. In 1647, Parliament outlawed the celebration of Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide. Christmas was outlawed in Boston from 1659.

Puritans objected to Christmas because the festivities surrounding the

holiday were seen as impious. (English jails were usually filled with

drunken revelers and brawlers.)

Puritans were opposed to Sunday sport or recreation because these distracted from religious observance of the Sabbath.

Other forms of leisure and entertainment were completely forbidden on

moral grounds. For example, Puritans were universally opposed to blood sports such as bearbaiting and cockfighting because they involved unnecessary injury to God's creatures. For similar reasons, they also opposed boxing. These sports were illegal in England during Puritan rule.

Card playing and gambling

were banned in England and the colonies (but card playing by itself was

generally considered acceptable), as was mixed dancing involving men

and women because it was thought to lead to fornication. Folk dance that did not involve close contact between men and women was considered appropriate. In New England, the first dancing school did not open until the end of the 17th century.

Puritans condemned the sexualization of the theatre and its associations with depravity and prostitution—London's theatres were located on the south side of the Thames, which was a center of prostitution. A major Puritan attack on the theatre was William Prynne's book Histriomastix.

Puritan authorities shut down English theatres in the 1640s and 1650s,

and none were allowed to open in Puritan-controlled colonies.

Puritans were not opposed to drinking alcohol in moderation. However, alehouses were closely regulated by Puritan-controlled governments in both England and America.

Early New England laws banning the sale of alcohol to Native Americans

were criticised because it was "not fit to deprive Indians of any

lawfull comfort aloweth to all men by the use of wine". Laws banned the

practice of individuals toasting each other, with the explanation that

it led to wasting God's gift of beer and wine, as well as being carnal.

Bounds were not set on enjoying sexuality within the bounds of marriage, as a gift from God.

Spouses were disciplined if they did not perform their sexual marital

duties, in accordance with 1 Corinthians 7 and other biblical passages.

Women and men were equally expected to fulfill marital responsibilities.

Women and men could file for divorce based on this issue alone. In

Massachusetts colony, which had some of the most liberal colonial

divorce laws, one out of every six divorce petitions was filed on the

basis on male impotence. Puritans publicly punished drunkenness and sexual relations outside marriage. Couples who had sex during their engagement were fined and publicly humiliated. Men, and a handful of women, who engaged in homosexual behavior, were seen as especially sinful, with some executed.

Opposition to other religious views

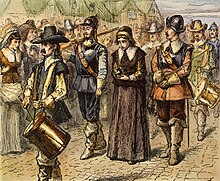

Quaker Mary Dyer led to execution on Boston Common, 1 June 1660, by an unknown 19th century artist

The Puritans exhibited intolerance to other religious views, including Quaker, Anglican and Baptist theologies. The Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were the most active of the New England persecutors of Quakers, and the persecuting spirit was shared by the Plymouth Colony and the colonies along the Connecticut river.

In 1660, one of the most notable victims of the religious intolerance was English Quaker Mary Dyer, who was hanged in Boston for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. She was one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs. The hanging of Dyer on Boston Common marked the beginning of the end of the Puritan theocracy. In 1661, King Charles II explicitly forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism. In 1684, England revoked the Massachusetts charter, sent over a royal governor to enforce English laws in 1686 and, in 1689, passed a broad Toleration Act.

The first two of the four Boston martyrs were executed by the

Puritans on 27 October 1659, and in memory of this, 27 October is now International Religious Freedom Day to recognise the importance of freedom of religion. Anti-Catholic sentiment appeared in New England with the first Pilgrim and Puritan settlers. In 1647, Massachusetts passed a law prohibiting any Jesuit Roman Catholic priests from entering territory under Puritan jurisdiction. Any suspected person who could not clear himself was to be banished from the colony; a second offense carried a death penalty.

Historiography

Second version of The Puritan, a late 19th-century sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The literature on Puritans, particularly biographical literature on

individual Puritan ministers, was already voluminous in the 17th century

and, indeed, the interests of Puritans in the narratives of early life

and conversions made the recording of the internal lives important to

them. The historical literature on Puritans is, however, quite

problematic and subject to controversies over interpretation. The early

writings are those of the defeated, excluded and victims. The great

interest of authors of the 19th century in Puritan figures was routinely

accused in the 20th century of consisting of anachronism and the reading back of contemporary concerns.

A debate continues on the definition of "Puritanism". English historian Patrick Collinson believes that "Puritanism had no content beyond what was attributed to it by its opponents." The analysis of "mainstream Puritanism" in terms of the evolution from it of Separatist and antinomian groups that did not flourish, and others that continue to this day, such as Baptists and Quakers,

can suffer in this way. The national context (England and Wales, as

well as the kingdoms of Scotland and Ireland) frames the definition of

Puritans, but was not a self-identification for those Protestants who

saw the progress of the Thirty Years' War

from 1620 as directly bearing on their denomination, and as a

continuation of the religious wars of the previous century, carried on

by the English Civil Wars. English historian Christopher Hill,

who has contributed to analyses of Puritan concerns that are more

respected than accepted, writes of the 1630s, old church lands, and the

accusations that William Laud was a crypto-Catholic:

To the heightened Puritan imagination it seemed that, all over Europe, the lamps were going out: the Counter-Reformation was winning back property for the church as well as souls: and Charles I and his government, if not allied to the forces of the Counter-Reformation, at least appeared to have set themselves identical economic and political objectives.

Puritans were politically important in England, but it is debated

whether the movement was in any way a party with policies and leaders

before the early 1640s. While Puritanism in New England was important

culturally for a group of colonial pioneers in America, there have been

many studies trying to pin down exactly what the identifiable cultural

component was. Fundamentally, historians remain dissatisfied with the

grouping as "Puritan" as a working concept for historical explanation.

The conception of a Protestant work ethic, identified more closely with Calvinist or Puritan principles, has been criticised at its root, mainly as a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy aligning economic success with a narrow religious scheme.

Puritans

- Peter Bulkley was an influential Puritan minister and founder of Concord.

- John Bunyan, famous for The Pilgrim's Progress

- William Bradford was Plymouth Colony's Governor.

- Anne Bradstreet was the first female to have her works published in the British North American colonies.

- Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader and eventually became Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. He was a very religious man and was considered an independent Puritan.

- John Endecott was the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and an important military leader.

- Jonathan Edwards, evangelical preacher who sparked the First Great Awakening

- Anne Hutchinson was a Puritan woman noted for speaking freely about her religious views, which resulted in her banishment from Massachusetts Bay Colony.

- John Milton is regarded as among the greatest English poets; author of epics like Paradise Lost, & dramas like Samson Agonistes. He was a staunch supporter of Cromwell.

- James Noyes was an influential Puritan minister, teacher and founder of Newbury.

- Thomas Parker was an influential Puritan minister, teacher and founder of Newbury.

- John Winthrop is noted for his sermon "A Model of Christian Charity" and as a leading figure in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

- Robert Woodford was an English lawyer, largely based at Northampton and London. His diary for the period 1637–1641 records in detail the outlook of an educated Puritan.