X-Ray Fluorescence for Metallic coatings

A Philips PW1606 X-ray fluorescence spectrometer with automated sample feed in a cement plant quality control laboratory

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) is the emission of characteristic "secondary" (or fluorescent) X-rays from a material that has been excited by being bombarded with high-energy X-rays or gamma rays. The phenomenon is widely used for elemental analysis and chemical analysis, particularly in the investigation of metals, glass, ceramics and building materials, and for research in geochemistry, forensic science, archaeology and art objects such as paintings and murals.

Underlying physics

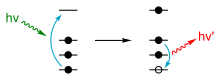

Figure 1: Physics of X-ray fluorescence in a schematic representation.

When materials are exposed to short-wavelength X-rays or to gamma rays, ionization of their component atoms

may take place. Ionization consists of the ejection of one or more

electrons from the atom, and may occur if the atom is exposed to

radiation with an energy greater than its ionization energy. X-rays and gamma rays can be energetic enough to expel tightly held electrons from the inner orbitals

of the atom. The removal of an electron in this way makes the

electronic structure of the atom unstable, and electrons in higher

orbitals "fall" into the lower orbital to fill the hole

left behind. In falling, energy is released in the form of a photon,

the energy of which is equal to the energy difference of the two

orbitals involved. Thus, the material emits radiation, which has energy

characteristic of the atoms present. The term fluorescence

is applied to phenomena in which the absorption of radiation of a

specific energy results in the re-emission of radiation of a different

energy (generally lower).

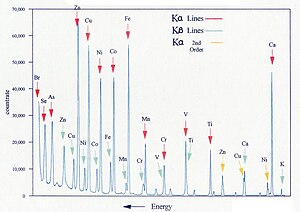

Figure 2: Typical wavelength dispersive XRF spectrum

Figure 3: Spectrum of a rhodium target tube operated at 60 kV, showing continuous spectrum and K lines

Characteristic radiation

Each element has electronic orbitals of characteristic

energy. Following removal of an inner electron by an energetic photon

provided by a primary radiation source, an electron from an outer shell

drops into its place. There are a limited number of ways in which this

can happen, as shown in Figure 1. The main transitions are given names:

an L→K transition is traditionally called Kα, an M→K transition is called Kβ, an M→L transition is called Lα,

and so on. Each of these transitions yields a fluorescent photon with a

characteristic energy equal to the difference in energy of the initial

and final orbital. The wavelength of this fluorescent radiation can be

calculated from Planck's Law:

The fluorescent radiation can be analysed either by sorting the energies of the photons (energy-dispersive analysis) or by separating the wavelengths of the radiation (wavelength-dispersive

analysis). Once sorted, the intensity of each characteristic radiation

is directly related to the amount of each element in the material. This

is the basis of a powerful technique in analytical chemistry. Figure 2 shows the typical form of the sharp fluorescent spectral lines obtained in the wavelength-dispersive method.

Primary radiation

In

order to excite the atoms, a source of radiation is required, with

sufficient energy to expel tightly held inner electrons. Conventional X-ray generators

are most commonly used, because their output can readily be "tuned" for

the application, and because higher power can be deployed relative to

other techniques. However, gamma ray sources can be used without the

need for an elaborate power supply, allowing an easier use in small

portable instruments. When the energy source is a synchrotron or the X-rays are focused by an optic like a polycapillary,

the X-ray beam can be very small and very intense. As a result, atomic

information on the sub-micrometre scale can be obtained. X-ray

generators in the range 20–60 kV are used, which allow excitation of a

broad range of atoms. The continuous spectrum consists of "bremsstrahlung"

radiation: radiation produced when high-energy electrons passing

through the tube are progressively decelerated by the material of the

tube anode (the "target"). A typical tube output spectrum is shown in

Figure 3.

Dispersion

In

energy dispersive analysis, the fluorescent X-rays emitted by the

material sample are directed into a solid-state detector which produces a

"continuous" distribution of pulses, the voltages of which are

proportional to the incoming photon energies. This signal is processed

by a multichannel analyser (MCA) which produces an accumulating digital

spectrum that can be processed to obtain analytical data.

In wavelength dispersive analysis, the fluorescent X-rays emitted

by the material sample are directed into a diffraction grating

monochromator. The diffraction grating used is usually a single crystal.

By varying the angle of incidence and take-off on the crystal, a single

X-ray wavelength can be selected. The wavelength obtained is given by Bragg's law:

where d is the spacing of atomic layers parallel to the crystal surface.

Detection

A portable XRF analyzer using a Silicon drift detector

In energy dispersive analysis, dispersion and detection are a single operation, as already mentioned above. Proportional counters or various types of solid-state detectors (PIN diode, Si(Li), Ge(Li), Silicon Drift Detector SDD) are used. They all share the same detection principle: An incoming X-ray photon

ionises a large number of detector atoms with the amount of charge

produced being proportional to the energy of the incoming photon. The

charge is then collected and the process repeats itself for the next

photon. Detector speed is obviously critical, as all charge carriers

measured have to come from the same photon to measure the photon energy

correctly (peak length discrimination is used to eliminate events that

seem to have been produced by two X-ray photons arriving almost

simultaneously). The spectrum is then built up by dividing the energy

spectrum into discrete bins and counting the number of pulses registered

within each energy bin. EDXRF

detector types vary in resolution, speed and the means of cooling (a

low number of free charge carriers is critical in the solid state

detectors): proportional counters with resolutions of several hundred eV

cover the low end of the performance spectrum, followed by PIN diode detectors, while the Si(Li), Ge(Li) and Silicon Drift Detectors (SDD) occupy the high end of the performance scale.

In wavelength dispersive analysis, the single-wavelength radiation produced by the monochromator is passed into a photomultiplier, a detector similar to a Geiger counter,

which counts individual photons as they pass through. The counter is a

chamber containing a gas that is ionised by X-ray photons. A central

electrode is charged at (typically) +1700 V with respect to the

conducting chamber walls, and each photon triggers a pulse-like cascade

of current across this field. The signal is amplified and transformed

into an accumulating digital count. These counts are then processed to

obtain analytical data.

X-ray intensity

The

fluorescence process is inefficient, and the secondary radiation is

much weaker than the primary beam. Furthermore, the secondary radiation

from lighter elements is of relatively low energy (long wavelength) and

has low penetrating power, and is severely attenuated if the beam passes

through air for any distance. Because of this, for high-performance

analysis, the path from tube to sample to detector is maintained under

vacuum (around 10 Pa residual pressure). This means in practice that

most of the working parts of the instrument have to be located in a

large vacuum chamber. The problems of maintaining moving parts in

vacuum, and of rapidly introducing and withdrawing the sample without

losing vacuum, pose major challenges for the design of the instrument.

For less demanding applications, or when the sample is damaged by a

vacuum (e.g. a volatile sample), a helium-swept X-ray chamber can be

substituted, with some loss of low-Z (Z = atomic number) intensities.

Chemical analysis

The use of a primary X-ray beam to excite fluorescent radiation from the sample was first proposed by Glocker and Schreiber in 1928.

Today, the method is used as a non-destructive analytical technique,

and as a process control tool in many extractive and processing

industries. In principle, the lightest element that can be analysed is beryllium

(Z = 4), but due to instrumental limitations and low X-ray yields for

the light elements, it is often difficult to quantify elements lighter

than sodium (Z = 11), unless background corrections and very comprehensive inter-element corrections are made.

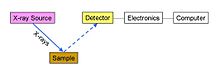

Figure 4: Schematic arrangement of EDX spectrometer

Energy dispersive spectrometry

In energy dispersive

spectrometers (EDX or EDS), the detector allows the determination of

the energy of the photon when it is detected. Detectors historically

have been based on silicon semiconductors, in the form of

lithium-drifted silicon crystals, or high-purity silicon wafers.

Figure 5: Schematic form of a Si(Li) detector

Si(Li) detectors

These

consist essentially of a 3–5 mm thick silicon junction type p-i-n diode

(same as PIN diode) with a bias of −1000 V across it. The

lithium-drifted centre part forms the non-conducting i-layer, where Li

compensates the residual acceptors which would otherwise make the layer

p-type. When an X-ray photon passes through, it causes a swarm of

electron-hole pairs to form, and this causes a voltage pulse. To obtain

sufficiently low conductivity, the detector must be maintained at low

temperature, and liquid-nitrogen cooling must be used for the best

resolution. With some loss of resolution, the much more convenient

Peltier cooling can be employed.

Wafer detectors

More recently, high-purity silicon wafers with low conductivity have become routinely available. Cooled by the Peltier effect, this provides a cheap and convenient detector, although the liquid nitrogen cooled Si(Li) detector still has the best resolution (i.e. ability to distinguish different photon energies).

Amplifiers

The pulses generated by the detector are processed by pulse-shaping

amplifiers. It takes time for the amplifier to shape the pulse for

optimum resolution, and there is therefore a trade-off between

resolution and count-rate: long processing time for good resolution

results in "pulse pile-up" in which the pulses from successive photons

overlap. Multi-photon events are, however, typically more drawn out in

time (photons did not arrive exactly at the same time) than single

photon events and pulse-length discrimination can thus be used to filter

most of these out. Even so, a small number of pile-up peaks will remain

and pile-up correction should be built into the software in

applications that require trace analysis. To make the most efficient use

of the detector, the tube current should be reduced to keep

multi-photon events (before discrimination) at a reasonable level, e.g.

5–20%.

Processing

Considerable

computer power is dedicated to correcting for pulse-pile up and for

extraction of data from poorly resolved spectra. These elaborate

correction processes tend to be based on empirical relationships that

may change with time, so that continuous vigilance is required in order

to obtain chemical data of adequate precision.

Usage

EDX spectrometers are different from WDX

spectrometers in that they are smaller, simpler in design and have

fewer engineered parts, however the accuracy and resolution of EDX

spectrometers are lower than for WDX. EDX spectrometers can also use

miniature X-ray tubes or gamma sources, which makes them cheaper and

allows miniaturization and portability. This type of instrument is

commonly used for portable quality control screening applications, such

as testing toys for lead (Pb) content, sorting scrap metals, and

measuring the lead content of residential paint. On the other hand, the

low resolution and problems with low count rate and long dead-time makes

them inferior for high-precision analysis. They are, however, very

effective for high-speed, multi-elemental analysis. Field Portable XRF

analysers currently on the market weigh less than 2 kg, and have limits

of detection on the order of 2 parts per million of lead (Pb) in pure

sand. Using a Scanning Electron Microscope and using EDX, studies have

been broadened to organic based samples such as biological samples and

polymers.

Figure 6: Schematic arrangement of wavelength dispersive spectrometer

Chemist operates a goniometer used for X-ray fluorescence analysis of individual grains of mineral specimens, U.S. Geological Survey, 1958.

Wavelength dispersive spectrometry

In wavelength dispersive spectrometers (WDX or WDS), the photons are separated by diffraction

on a single crystal before being detected. Although wavelength

dispersive spectrometers are occasionally used to scan a wide range of

wavelengths, producing a spectrum plot as in EDS, they are usually set

up to make measurements only at the wavelength of the emission lines of

the elements of interest. This is achieved in two different ways:

- "Simultaneous" spectrometers have a number of "channels" dedicated to analysis of a single element, each consisting of a fixed-geometry crystal monochromator, a detector, and processing electronics. This allows a number of elements to be measured simultaneously, and in the case of high-powered instruments, complete high-precision analyses can be obtained in under 30 s. Another advantage of this arrangement is that the fixed-geometry monochromators have no continuously moving parts, and so are very reliable. Reliability is important in production environments where instruments are expected to work without interruption for months at a time. Disadvantages of simultaneous spectrometers include relatively high cost for complex analyses, since each channel used is expensive. The number of elements that can be measured is limited to 15–20, because of space limitations on the number of monochromators that can be crowded around the fluorescing sample. The need to accommodate multiple monochromators means that a rather open arrangement around the sample is required, leading to relatively long tube-sample-crystal distances, which leads to lower detected intensities and more scattering. The instrument is inflexible, because if a new element is to be measured, a new measurement channel has to be bought and installed.

- "Sequential" spectrometers have a single variable-geometry monochromator (but usually with an arrangement for selecting from a choice of crystals), a single detector assembly (but usually with more than one detector arranged in tandem), and a single electronic pack. The instrument is programmed to move through a sequence of wavelengths, in each case selecting the appropriate X-ray tube power, the appropriate crystal, and the appropriate detector arrangement. The length of the measurement program is essentially unlimited, so this arrangement is very flexible. Because there is only one monochromator, the tube-sample-crystal distances can be kept very short, resulting in minimal loss of detected intensity. The obvious disadvantage is relatively long analysis time, particularly when many elements are being analysed, not only because the elements are measured in sequence, but also because a certain amount of time is taken in readjusting the monochromator geometry between measurements. Furthermore, the frenzied activity of the monochromator during an analysis program is a challenge for mechanical reliability. However, modern sequential instruments can achieve reliability almost as good as that of simultaneous instruments, even in continuous-usage applications.

Sample preparation

In

order to keep the geometry of the tube-sample-detector assembly

constant, the sample is normally prepared as a flat disc, typically of

diameter 20–50 mm. This is located at a standardized, small distance

from the tube window. Because the X-ray intensity follows an

inverse-square law, the tolerances for this placement and for the

flatness of the surface must be very tight in order to maintain a

repeatable X-ray flux. Ways of obtaining sample discs vary: metals may

be machined to shape, minerals may be finely ground and pressed into a

tablet, and glasses may be cast to the required shape. A further reason

for obtaining a flat and representative sample surface is that the

secondary X-rays from lighter elements often only emit from the top few

micrometres of the sample. In order to further reduce the effect of

surface irregularities, the sample is usually spun at 5–20 rpm. It is

necessary to ensure that the sample is sufficiently thick to absorb the

entire primary beam. For higher-Z materials, a few millimetres thickness

is adequate, but for a light-element matrix such as coal, a thickness

of 30–40 mm is needed.

Figure 7: Bragg diffraction condition

Monochromators

The

common feature of monochromators is the maintenance of a symmetrical

geometry between the sample, the crystal and the detector. In this

geometry the Bragg diffraction condition is obtained.

The X-ray emission lines are very narrow (see figure 2), so the

angles must be defined with considerable precision. This is achieved in

two ways:

- Flat crystal with Soller collimators

The Soller collimator is a stack of parallel metal plates, spaced a

few tenths of a millimetre apart. To improve angle resolution, one must

lengthen the collimator, and/or reduce the plate spacing. This

arrangement has the advantage of simplicity and relatively low cost, but

the collimators reduce intensity and increase scattering, and reduce

the area of sample and crystal that can be "seen". The simplicity of the

geometry is especially useful for variable-geometry monochromators.

Figure 8: Flat crystal with Soller collimators

Figure 9: Curved crystal with slits

- Curved crystal with slits

The Rowland circle geometry ensures that the slits are both in focus,

but in order for the Bragg condition to be met at all points, the

crystal must first be bent to a radius of 2R (where R is the radius of

the Rowland circle), then ground to a radius of R. This arrangement

allows higher intensities (typically 8-fold) with higher resolution

(typically 4-fold) and lower background. However, the mechanics of

keeping Rowland circle geometry in a variable-angle monochromator is

extremely difficult. In the case of fixed-angle monochromators (for use

in simultaneous spectrometers), crystals bent to a logarithmic spiral

shape give the best focusing performance. The manufacture of curved

crystals to acceptable tolerances increases their price considerably.

Crystals

The desirable characteristics of a diffraction crystal are:

- High diffraction intensity

- High dispersion

- Narrow diffracted peak width

- High peak-to-background

- Absence of interfering elements

- Low thermal coefficient of expansion

- Stability in air and on exposure to X-rays

- Ready availability

- Low cost

Crystals with simple structure tend to give the best diffraction

performance. Crystals containing heavy atoms can diffract well, but also

fluoresce themselves, causing interference. Crystals that are

water-soluble, volatile or organic tend to give poor stability.

Commonly used crystal materials include LiF (lithium fluoride),

ADP (ammonium dihydrogen phosphate), Ge (germanium), graphite, InSb

(indium antimonide), PE (tetrakis-(hydroxymethyl)-methane:

penta-erythritol), KAP (potassium hydrogen phthalate), RbAP (rubidium

hydrogen phthalate) and TlAP (thallium(I) hydrogen phthalate). In

addition, there is an increasing use of "layered synthetic

microstructures", which are "sandwich" structured materials comprising

successive thick layers of low atomic number matrix, and monatomic

layers of a heavy element. These can in principle be custom-manufactured

to diffract any desired long wavelength, and are used extensively for

elements in the range Li to Mg.

Detectors

Detectors

used for wavelength dispersive spectrometry need to have high pulse

processing speeds in order to cope with the very high photon count rates

that can be obtained. In addition, they need sufficient energy

resolution to allow filtering-out of background noise and spurious

photons from the primary beam or from crystal fluorescence. There are

four common types of detector:

- Gas flow proportional counters

- Sealed gas detectors

- Scintillation counters

- Semiconductor detectors

Figure 10: Arrangement of gas flow proportional counter

Gas flow proportional counters are used mainly for detection

of longer wavelengths. Gas flows through it continuously. Where there

are multiple detectors, the gas is passed through them in series, then

led to waste. The gas is usually 90% argon, 10% methane ("P10"),

although the argon may be replaced with neon or helium where very long

wavelengths (over 5 nm) are to be detected. The argon is ionised by

incoming X-ray photons, and the electric field multiplies this charge

into a measurable pulse. The methane suppresses the formation of

fluorescent photons caused by recombination of the argon ions with stray

electrons. The anode wire is typically tungsten or nichrome of 20–60 μm

diameter. Since the pulse strength obtained is essentially proportional

to the ratio of the detector chamber diameter to the wire diameter, a

fine wire is needed, but it must also be strong enough to be maintained

under tension so that it remains precisely straight and concentric with

the detector. The window needs to be conductive, thin enough to transmit

the X-rays effectively, but thick and strong enough to minimize

diffusion of the detector gas into the high vacuum of the monochromator

chamber. Materials often used are beryllium metal, aluminised PET film

and aluminised polypropylene. Ultra-thin windows (down to 1 μm) for use

with low-penetration long wavelengths are very expensive. The pulses

are sorted electronically by "pulse height selection" in order to

isolate those pulses deriving from the secondary X-ray photons being

counted.

Sealed gas detectors are similar to the gas flow

proportional counter, except that the gas does not flow through it. The

gas is usually krypton or xenon at a few atmospheres pressure. They are

applied usually to wavelengths in the 0.15–0.6 nm range. They are

applicable in principle to longer wavelengths, but are limited by the

problem of manufacturing a thin window capable of withstanding the high

pressure difference.

Scintillation counters consist of a scintillating crystal

(typically of sodium iodide doped with thallium) attached to a

photomultiplier. The crystal produces a group of scintillations for each

photon absorbed, the number being proportional to the photon energy.

This translates into a pulse from the photomultiplier of voltage

proportional to the photon energy. The crystal must be protected with a

relatively thick aluminium/beryllium foil window, which limits the use

of the detector to wavelengths below 0.25 nm. Scintillation counters are

often connected in series with a gas flow proportional counter: the

latter is provided with an outlet window opposite the inlet, to which

the scintillation counter is attached. This arrangement is particularly

used in sequential spectrometers.

Semiconductor detectors can be used in theory, and their

applications are increasing as their technology improves, but

historically their use for WDX has been restricted by their slow

response.

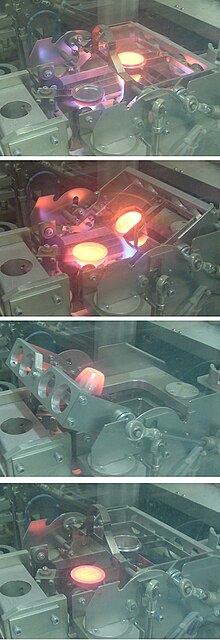

A

glass "bead" specimen for XRF analysis being cast at around 1100 °C in a

Herzog automated fusion machine in a cement plant quality control

laboratory. 1 (top): fusing, 2: preheating the mould, 3: pouring the

melt, 4: cooling the "bead"

Extracting analytical results

At

first sight, the translation of X-ray photon count-rates into elemental

concentrations would appear to be straightforward: WDX separates the

X-ray lines efficiently, and the rate of generation of secondary photons is proportional to the element concentration. However, the number of photons leaving the sample is also affected by the physical properties of the sample: so-called "matrix effects". These fall broadly into three categories:

- X-ray absorption

- X-ray enhancement

- Sample macroscopic effects

All elements absorb X-rays to some extent. Each element has a

characteristic absorption spectrum which consists of a "saw-tooth"

succession of fringes, each step-change of which has wavelength close to

an emission line of the element. Absorption attenuates the secondary

X-rays leaving the sample. For example, the mass absorption coefficient

of silicon at the wavelength of the aluminium Kα line is 50 m²/kg,

whereas that of iron is 377 m²/kg. This means that a given concentration

of aluminium in a matrix of iron gives only one seventh of the count

rate

compared with the same concentration of aluminium in a silicon matrix.

Fortunately, mass absorption coefficients are well known and can be

calculated. However, to calculate the absorption for a multi-element

sample, the composition must be known. For analysis of an unknown

sample, an iterative procedure is therefore used. It will be noted that,

to derive the mass absorption accurately, data for the concentration of

elements not measured by XRF may be needed, and various strategies are

employed to estimate these. As an example, in cement analysis, the

concentration of oxygen (which is not measured) is calculated by

assuming that all other elements are present as standard oxides.

Enhancement occurs where the secondary X-rays emitted by a

heavier element are sufficiently energetic to stimulate additional

secondary emission from a lighter element. This phenomenon can also be

modelled, and corrections can be made provided that the full matrix

composition can be deduced.

Sample macroscopic effects consist of effects of

inhomogeneities of the sample, and unrepresentative conditions at its

surface. Samples are ideally homogeneous and isotropic, but they often

deviate from this ideal. Mixtures of multiple crystalline components in

mineral powders can result in absorption effects that deviate from those

calculable from theory. When a powder is pressed into a tablet, the

finer minerals concentrate at the surface. Spherical grains tend to

migrate to the surface more than do angular grains. In machined metals,

the softer components of an alloy tend to smear across the surface.

Considerable care and ingenuity are required to minimize these effects.

Because they are artifacts of the method of sample preparation, these

effects can not be compensated by theoretical corrections, and must be

"calibrated in". This means that the calibration materials and the

unknowns must be compositionally and mechanically similar, and a given

calibration is applicable only to a limited range of materials. Glasses

most closely approach the ideal of homogeneity and isotropy, and for

accurate work, minerals are usually prepared by dissolving them in a

borate glass, and casting them into a flat disc or "bead". Prepared in

this form, a virtually universal calibration is applicable.

Further corrections that are often employed include background

correction and line overlap correction. The background signal in an XRF

spectrum derives primarily from scattering of primary beam photons by

the sample surface. Scattering varies with the sample mass absorption,

being greatest when mean atomic number is low. When measuring trace

amounts of an element, or when measuring on a variable light matrix,

background correction becomes necessary. This is really only feasible on

a sequential spectrometer. Line overlap is a common problem, bearing in

mind that the spectrum of a complex mineral can contain several hundred

measurable lines. Sometimes it can be overcome by measuring a

less-intense, but overlap-free line, but in certain instances a

correction is inevitable. For instance, the Kα is the only usable line

for measuring sodium, and it overlaps the zinc Lβ (L2-M4) line. Thus zinc, if present, must be analysed in order to properly correct the sodium value.

Other spectroscopic methods using the same principle

It is also possible to create a characteristic secondary X-ray emission using other incident radiation to excite the sample:

- Electron beam: electron microprobe;

- Ion beam: particle induced X-ray emission (PIXE).

When radiated by an X-ray beam, the sample also emits other radiations that can be used for analysis:

- Electrons ejected by the photoelectric effect: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), also called electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis (ESCA)

The de-excitation also ejects Auger electrons, but Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) normally uses an electron beam as the probe.

Confocal microscopy

X-ray fluorescence imaging is a newer technique that allows control

over depth, in addition to horizontal and vertical aiming, for example,

when analysing buried layers in a painting.