Criticism of the War on Terror addresses the morals, ethics, efficiency, economics, as well as other issues surrounding the War on Terror. It also touches upon criticism against the phrase itself, which was branded as a misnomer. The notion of a "war" against "terrorism" has proven highly contentious, with critics charging that participating governments exploited it to pursue long-standing policy/military objectives, reduce civil liberties, and infringe upon human rights. It is argued that the term war is not appropriate in this context (as in War on Drugs), since there is no identifiable enemy and that it is unlikely international terrorism can be brought to an end by military means.

Other critics, such as Francis Fukuyama, note that "terrorism" is not an enemy, but a tactic: calling it a "war on terror" obscures differences between conflicts such as anti-occupation insurgents and international mujahideen. With a military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan and its associated collateral damage Shirley Williams maintains this increases resentment and terrorist threats against the West. Other criticism include United States hypocrisy, media induced hysteria, and that changes in American foreign and security policy have shifted world opinion against the US.

Terminology

Various critics dubbed the term "War on Terror" as nonsensical.

For example, billionaire activist investor George Soros criticized the term "War on Terror" as a "false metaphor."

Linguist George Lakoff of the Rockridge Institute argued that there cannot literally be a war on terror, since terror is an abstract noun. "Terror cannot be destroyed by weapons or signing a peace treaty. A war on terror has no end."

Jason Burke, a journalist who writes about radical Islamic activity, describes the terms "terrorism" and "war against terrorism" in this manner:

There are multiple ways of defining terrorism and all are subjective. Most define terrorism as 'the use or threat of serious violence' to advance some kind of 'cause'. Some state clearly the kinds of group ('sub-national', 'non-state') or cause (political, ideological, religious) to which they refer. Others merely rely on the instinct of most people when confronted with an act that involves innocent civilians being killed or maimed by men armed with explosives, firearms or other weapons. None is satisfactory and grave problems with the use of the term persist. Terrorism is after all, a tactic. The term 'war on terrorism' is thus effectively nonsensical. As there is no space here to explore this involved and difficult debate, my preference is, on the whole, for the less loaded term 'militancy'. This is not an attempt to condone such actions, merely to analyze them in a clearer way.

Perpetual war

Former U.S. President George W. Bush articulated the goals of the War on Terror in a September 20, 2001 speech, in which he said that it "will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated."

In that same speech, he called the war "a task that does not end", an

argument he reiterated in 2006 State of The Union address.

Preventive war

One justification given for the invasion of Iraq was to prevent terroristic, or other attacks, by Iraq on the United States or other nations. This can be viewed as a conventional warfare realization of the War on Terror.

A major criticism leveled at this justification is that it does not fulfill one of the requirements of a just war and that in waging war preemptively, the United States undermined international law and the authority of the United Nations, particularly the United Nations Security Council.

On this ground, by invading a country that did not pose an imminent

threat without UN support, the U.S. violated international law,

including the UN Charter and the Nuremberg principles, therefore committing a war of aggression, which is considered a war crime. Additional criticism raised the point that the United States might have set a precedent, under the premise of which any nation could justify the invasion of other states.

Richard N. Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, argues that on the eve of U.S. intervention in 2003, Iraq represented, at best, a gathering threat and not an imminent one.

In hindsight he notes that Iraq did not even represent a gathering

threat. "The decision to attack Iraq in March 2003 was discretionary: it

was a war of choice. There was no vital American interests in imminent

danger and there were alternatives to using military force, such as

strengthening existing sanctions."

However, Haass argues that U.S. intervention in Afghanistan in 2001

began as a war of necessity—vital interests were at stake—but morphed

"into something else and it crossed a line in March 2009, when President

Barack Obama`

decided to sharply increase American troop levels and declared that it

was U.S. policy to 'take the fight to the Taliban in the south and east'

of the country." Afghanistan, according to Haass, eventually became a war of choice.

War on Terror seen as pretext

Excerpts

from an April 2006 report compiled from sixteen U.S. government

intelligence agencies has strengthened the claim that engaging in Iraq

has increased terrorism in the region.

Domestic civil liberties

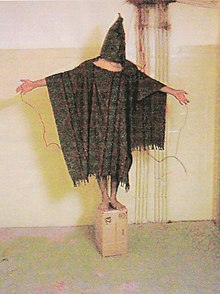

Picture of Satar Jabar, one of the prisoners subjected to torture at Abu Ghraib. Abar was in Abu Ghraib for carjacking.

In the United Kingdom, critics have claimed that the Blair government used the War on Terror as a pretext to radically curtail civil liberties, some enshrined in law since Magna Carta. For example, the detention-without-trial in Belmarsh prison: controls on free speech through laws against protests near Parliament and laws banning the "glorification" of terrorism: and reductions in checks on police power, as in the case of Jean Charles de Menezes and Mohammed Abdul Kahar.

Former Liberal Democrat Leader Sir Menzies Campbell has also condemned Blair's inaction over the controversial U.S. practice of extraordinary rendition, arguing that the human rights conventions to which the UK is a signatory (e.g. European Convention on Human Rights) impose on the government a "legal obligation" to investigate and prevent potential torture and human rights violations.

Unilateralism

U.S. President George W. Bush's remark of November 2001 claiming that "You're either with us or you are with the terrorists,"

has been a source of criticism. Thomas A. Keaney of Johns Hopkins

University's Foreign Policy Institute said "it made diplomacy with a

number of different countries far more difficult because obviously there

are different problems throughout the world."

As a war against Islam

Since the War on Terror revolved primarily around the United States

and other NATO states intervening in the internal affairs of Muslim

countries (i.e. in Iraq, Afghanistan, etc.) and organisations, it has been labelled a war against Islam by ex-United States Attorney General Ramsey Clark, among others.

After his release from Guantanamo in 2005, ex-detainee Moazzam Begg appeared in the Islamist propaganda video 21st Century CrUSAders and claimed the U.S. was engaging in a new crusade:

I think that history is definitely repeating itself and for the Muslim world and I think even a great part of the non-Muslim world now, are beginning to recognize that there are ambitions that the United States has on the lands and wealth of nations of Islam.

Methods

Protestors dressed as hooded detainees and holding WCW signs in Washington DC on January 4, 2007

Aiding terrorism

Each month, there are

more suicide terrorists trying to kill Americans and their allies in

Afghanistan, Iraq, as well as other Muslim countries than in all the

years before 2001 combined. From 1980 to 2003, there were 343

suicide attacks around the world and at most 10 percent were

anti-American inspired. Since 2004, there have been more than 2,000,

over 91 percent against U.S. and allied forces in Afghanistan, Iraq, as

well as other countries.

Robert Pape

University of Chicago professor and political scientist, Robert Pape has written extensive work on suicide terrorism and states that it is triggered by military occupations, not extremist ideologies. In works such as Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism and Cutting the Fuse,

he uses data from an extensive terrorism database and argues that by

increasing military occupations, the US government is increasing

terrorism. Pape is also the director and founder of the Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (CPOST), a database of every known suicide terrorist attack from 1980 to 2008.

In 2006, a National Intelligence Estimate

stated that the war in Iraq has increased the threat of terrorism. The

estimate was compiled by 16 intelligence agencies and was the first

assessment of global terrorism since the start of the Iraq war.

Cornelia Beyer explains how terrorism increased as a response to

past and present military intervention and occupation, as well as to

'structural violence'. Structural violence, in this instance, refers to

economic conditions of backwardness which are attributed to the economic

policies of the Western nations, the United States in particular.

British Liberal Democrat politician Shirley Williams

wrote that the United States and United Kingdom governments "must stop

to think whether it is sowing the kind of resentment which is the

seedbed of future terrorism." The United Kingdom ambassador to Italy, Ivor Roberts, echoed this criticism when he stated that President Bush was "the best recruiting sergeant ever for al Qaeda."

The United States also granted "protected persons" status under the Geneva Convention to the Mojahedin-e-Khalq, an Iranian group classified by the U.S. Department of State as a terrorist organization, sparking criticism.

Other critics further noted that the American government granted

political asylum to several alleged terrorists and terrorist

organizations that seek to overthrow Fidel Castro's regime, while the American government claims to be anti-terrorism.

In 2018, New York Times terrorism reporter Rukmini

Callimachi said "there are more terrorists now than there are on the eve

of September 11, not less...There are more terror groups now, not

less."

Hypocrisy of the Bush Administration

The alleged mastermind behind the September 11, 2001 attacks was part of the mujahideen who were sponsored, armed, trained and aided by the CIA to fight the Soviet Union after it intervened in Afghanistan in 1979.

Venezuela accused the U.S. government of having a double standard towards terrorism for giving safe haven to Luis Posada Carriles. Some Americans also commented on the selective use of the term War on Terrorism, including 3 star general William Odom, formerly President Reagan's NSA Director, who wrote:

As many critics have pointed, out, terrorism is not an enemy. It is a tactic. Because the United States itself has a long record of supporting terrorists and using terrorist tactics, the slogans of today's war on terrorism merely makes the United States look hypocritical to the rest of the world. A prudent American president would end the present policy of "sustained hysteria" over potential terrorist attacks..treat terrorism as a serious but not a strategic problem, encourage Americans to regain their confidence and refuse to let al Qaeda keep us in a state of fright.

Misleading information

In

the months leading up to the invasion of Iraq, President Bush and

members of his administration indicated they possessed information which

demonstrated a link between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda. Published reports of the links began in late December 1998. In January 1999, Newsweek

magazine published a story about Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda joining

forces to attack U.S. interests in the Gulf Region. ABC News broadcast a

story of this link soon after. The Bush Administration believed there was a possibility of a potential collaboration between al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath regime following the U.S. led invasion of Afghanistan. Amnesty International Secretary General Irene Khan criticized the use of pro-humanitarian arguments by Coalition countries prior to its 2003 invasion of Iraq,

writing in an open letter: "This selective attention to human rights is

nothing but a cold and calculated manipulation of the work of human

rights activists. Let us not forget that these same governments turned a

blind eye to Amnesty International's reports of widespread human rights

violations in Iraq before the Gulf War."

Torture by proxy

The term "torture by proxy" is used by some critics to describe situations in which the CIA

and other US agencies transferred supposed terrorists, whom they

captured during their efforts in the 'War on terrorism', to countries

known to employ torture

as an interrogation technique. Some also claimed that US agencies knew

torture was employed, even though the transfer of anyone to anywhere for

the purpose of torture is a violation of US law. Nonetheless, Condoleezza Rice (then the United States Secretary of State) stated that:

the United States has not transported anyone and will not transport anyone, to a country when we believe he will be tortured. Where appropriate, the United States seeks assurances that transferred persons will not be tortured.

This US programme also prompted several official investigations in

Europe into alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers

involving Council of Europe member states, including those related with the so-called War on Terrorism. A June 2006 report

from the Council of Europe estimated that 100 people were kidnapped by

the CIA on EU territory with the cooperation of Council of Europe

members and rendered to other countries, often after having transited

through secret detention centres ("black sites"), some located in Europe, utilised by the CIA. According to the separate European Parliament report of February 2007,

the CIA has conducted 1,245 flights, many of them to destinations where

these alleged 'terrorists' could face torture, in violation of article 3

of the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

Religionism and Islamophobia

One aspect of the criticism regarding the rhetoric justifying the War on Terror was religionism, or more specifically Islamophobia.

Theologian Lawrence Davidson, who studies contemporary Muslims

societies in North America, defines this concept as a stereotyping of

all followers of Islam as real or potential terrorists due to alleged

hateful and violent teaching of their religion. He goes on to argue that

"Islam is reduced to the concept of jihad and Jihad is reduced to

terror against the West." This line of argument echoes Edward Said’s famous piece Orientalism

in which he argued that the United States sees the Muslims and Arabs in

an essentialized caricatures – as oil supplies or potential terrorists.

Decreasing international support

In 2002, strong majorities supported the U.S.-led War on Terror in Britain, France, Germany, Japan, India and Russia, according to a sample survey conducted by the Pew Research Center.

By 2006, supporters of the effort were in the minority in Britain

(49%), Germany (47%), France (43%) and Japan (26%). Although a majority

of Russians still supported the War on Terror, that majority had

decreased by 21%. Whereas 63% of Spaniards supported the War on Terror

in 2003, only 19% of the population indicated support in 2006. 19% of

the Chinese population still supports the War on Terror and less than a

fifth of the populations of Turkey, Egypt, as well as Jordan support the efforts. The report also indicated that Indian public support for the War on Terror has been stable. Andrew Kohut, while speaking to the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, noted that and according to the Pew Research Center

polls conducted in 2004, "the ongoing conflict in Iraq continues to

fuel anti-American sentiments. America’s global popularity plummeted at

the start of military action in Iraq and the U.S. presence there remains

widely unpopular."

Marek Obrtel, former Lieutenant Colonel in Field Hospital with Czech Republic army, returned his medals which he received during his posting in Afghanistan War for NATO operations. He criticized the War on Terror

as describing the mission as "deeply ashamed that I served a criminal

organization such as NATO, led by the USA and its perverse interests

around the world."

Role of U.S. media

Researchers

in communication studies and political science found that American

understanding of the "War on Terror" is directly shaped by how

mainstream news media reports events associated with the conflict. In Bush's War: Media Bias and Justifications for War in a Terrorist Age political communication researcher Jim A. Kuypers

illustrated "how the press failed America in its coverage on the War on

Terror." In each comparison, Kuypers "detected massive bias on the part

of the press." This researcher called the mainstream news media an

"anti-democratic institution" in his conclusion. "What has essentially

happened since 9/11 has been that Bush has repeated the same themes and

framed those themes the same whenever discussing the War on Terror,"

said Kuypers. "Immediately following 9/11, the mainstream news media

(represented by CBS, ABC, NBC, USA Today, The New York Times, as well as The Washington Post)

did echo Bush, but within eight weeks it began to intentionally ignore

certain information the president was sharing and instead reframed the

president's themes or intentionally introduced new material to shift the

focus."

This goes beyond reporting alternate points of view, which is an

important function of the press. "In short," Kuypers explained, "if

someone were relying only on the mainstream media for information, they

would have no idea what the president actually said. It was as if the

press were reporting on a different speech." The study is essentially a

"comparative framing analysis." Overall, Kuypers examined themes about

9-11 and the War on Terror that President Bush used and compared them to

themes that the press used when reporting on what he said.

"Framing is a process whereby communicators, consciously or

unconsciously, act to construct a point of view that encourages the

facts of a given situation to be interpreted by others in a particular

manner," wrote Kuypers. These findings suggest that the public is

misinformed about government justification and plans concerning the War

on Terror.

Others have also suggested that press coverage contributed to a

public confused and misinformed on both the nature and level of the

threat to the U.S. posed by terrorism. In his book, Trapped in the War on Terror

political scientist Ian S. Lustick, claimed, "The media have given

constant attention to possible terrorist-initiated catastrophes and to

the failures and weaknesses of the government's response." Lustick

alleged that the War on Terror is disconnected from the real but remote

threat terrorism poses and that the generalized War on Terror began as

part of the justification for invading Iraq, but then took on a life of

its own, fueled by media coverage. Scott Atran

writes that "publicity is the oxygen of terrorism" and the rapid

growth of international communicative networks renders publicity even

more potent, with the result that "perhaps never in the history of human

conflict have so few people with so few actual means and capabilities

frightened so many."

Media researcher Stephen D. Cooper's analysis of media criticism Watching the Watchdog: Bloggers As the Fifth Estate

contains several examples of controversies concerning mainstream

reporting of the War on Terror. Cooper found that bloggers' criticisms

of factual inaccuracies in news stories or bloggers' discovery of the

mainstream press' failure to adequately verify facts before publication

caused many news organizations to retract or change news stories.

Cooper found that bloggers specializing in criticism of media coverage advanced four key points:

- Mainstream reporting of the War on Terror has frequently contained factual inaccuracies. In some cases, the errors go uncorrected: moreover, when corrections are issued they usually are given far less prominence than the initial coverage containing the errors.

- The mainstream press has sometimes failed to check the provenance of information or visual images supplied by Iraqi "stringers" (local Iraqis hired to relay local news).

- Story framing is often problematic: in particular, "man-in-the-street" interviews have often been used as a representation of public sentiment in Iraq, in place of methodologically sound survey data.

- Mainstream reporting has tended to concentrate on the more violent areas of Iraq, with little or no reporting of the calm areas.

David Barstow won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting

by connecting the Department of Defense to over 75 retired generals

supporting the Iraq War on television and radio networks. The Department

of Defense recruited retired generals to promote the war to the

American public. Barstow also discovered undisclosed links between some

retired generals and defense contractors. He reported that "the Bush

administration used its control over access of information in an effort

to transform the analysts into a kind of media Trojan horse".

British objections

The Director of Public Prosecutions and head of the Crown Prosecution Service in the UK, Ken McDonald, Britain's most senior criminal prosecutor, stated that those responsible for acts of terrorism such as the 7 July 2005 London bombings are not "soldiers" in a war, but "inadequates" who should be dealt with by the criminal justice system.

He added that a "culture of legislative restraint" was needed in

passing anti-terrorism laws and that a "primary purpose" of the violent

attacks was to tempt countries such as Britain to "abandon our values."

He stated that in the eyes of the UK criminal justice system, the

response to terrorism had to be "proportionate and grounded in due process and the rule of law":

London is not a battlefield. Those innocents who were murdered...were not victims of war. And the men who killed them were not, as in their vanity they claimed on their ludicrous videos, 'soldiers'. They were deluded, narcissistic inadequates. They were criminals. They were fantasists. We need to be very clear about this. On the streets of London there is no such thing as a war on terror. The fight against terrorism on the streets of Britain is not a war. It is the prevention of crime, the enforcement of our laws and the winning of justice for those damaged by their infringement.

Stella Rimington, former head of the British intelligence service MI5

criticised the War on Terror as a "huge overreaction" and had decried

the militarization and politicization of U.S. efforts to be the wrong

approach to terrorism. David Miliband, former UK foreign secretary, has similarly called the strategy a "mistake". Nigel Lawson, former Chancellor of the Exchequer, called for Britain to end its involvement in the War in Afghanistan, describing the mission as "wholly unsuccessful and indeed counter-productive."