| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

4-Aminobutanoic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.235 |

| EC Number | 200-258-6 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | gamma-Aminobutyric+Acid |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number | ES6300000 |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C4H9NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 103.120 g/mol |

| Appearance | white microcrystalline powder |

| Density | 1.11 g/mL |

| Melting point | 203.7 °C (398.7 °F; 476.8 K) |

| Boiling point | 247.9 °C (478.2 °F; 521.0 K) |

| 130 g/100 mL | |

| log P | −3.17 |

| Acidity (pKa) |

|

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Irritant, Harmful |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

12,680 mg/kg (mouse, oral) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

gamma-Aminobutyric acid, or γ-aminobutyric acid /ˈɡæmə

GABA is sold as a dietary supplement.

Function

Neurotransmitter

GABA metabolism, involvement of glial cells

In vertebrates, GABA acts at inhibitory synapses in the brain by binding to specific transmembrane receptors in the plasma membrane of both pre- and postsynaptic neuronal processes. This binding causes the opening of ion channels to allow the flow of either negatively charged chloride ions into the cell or positively charged potassium ions out of the cell. This action results in a negative change in the transmembrane potential, usually causing hyperpolarization. Two general classes of GABA receptor are known:

- GABAA in which the receptor is part of a ligand-gated ion channel complex

- GABAB metabotropic receptors, which are G protein-coupled receptors that open or close ion channels via intermediaries (G proteins)

The production, release, action, and degradation of GABA at a stereotyped GABAergic synapse

Neurons that produce GABA as their output are called GABAergic

neurons, and have chiefly inhibitory action at receptors in the adult

vertebrate. Medium spiny cells are a typical example of inhibitory central nervous system GABAergic cells. In contrast, GABA exhibits both excitatory and inhibitory actions in insects, mediating muscle activation at synapses between nerves and muscle cells, and also the stimulation of certain glands. In mammals, some GABAergic neurons, such as chandelier cells, are also able to excite their glutamatergic counterparts.

GABAA receptors are ligand-activated chloride channels: when activated by GABA, they allow the flow of chloride

ions across the membrane of the cell. Whether this chloride flow is

depolarizing (makes the voltage across the cell's membrane less

negative), shunting (has no effect on the cell's membrane potential), or

inhibitory/hyperpolarizing (makes the cell's membrane more negative)

depends on the direction of the flow of chloride. When net chloride

flows out of the cell, GABA is depolarising; when chloride flows into

the cell, GABA is inhibitory or hyperpolarizing. When the net flow of

chloride is close to zero, the action of GABA is shunting. Shunting inhibition

has no direct effect on the membrane potential of the cell; however, it

reduces the effect of any coincident synaptic input by reducing the electrical resistance

of the cell's membrane. Shunting inhibition can "override" the

excitatory effect of depolarising GABA, resulting in overall inhibition

even if the membrane potential becomes less negative. It was thought

that a developmental switch in the molecular machinery controlling the

concentration of chloride inside the cell changes the functional role of

GABA between neonatal and adult stages. As the brain develops into adulthood, GABA's role changes from excitatory to inhibitory.

Brain development

While

GABA is an inhibitory transmitter in the mature brain, its actions were

thought to be primarily excitatory in the developing brain.

The gradient of chloride was reported to be reversed in immature

neurons, with its reversal potential higher than the resting membrane

potential of the cell; activation of a GABA-A receptor thus leads to

efflux of Cl− ions from the cell (that is, a depolarizing

current). The differential gradient of chloride in immature neurons was

shown to be primarily due to the higher concentration of NKCC1

co-transporters relative to KCC2 co-transporters in immature cells.

GABAergic interneurons mature faster in the hippocampus and the GABA

signalling machinery appears earlier than glutamatergic transmission.

Thus, GABA is considered the major excitatory neurotransmitter in many

regions of the brain before the maturation of glutamatergic synapses.

In the developmental stages preceding the formation of synaptic contacts, GABA is synthesized by neurons and acts both as an autocrine (acting on the same cell) and paracrine (acting on nearby cells) signalling mediator. The ganglionic eminences also contribute greatly to building up the GABAergic cortical cell population.

GABA regulates the proliferation of neural progenitor cells the migration and differentiation the elongation of neurites and the formation of synapses.

GABA also regulates the growth of embryonic and neural stem cells. GABA can influence the development of neural progenitor cells via brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression. GABA activates the GABAA receptor, causing cell cycle arrest in the S-phase, limiting growth.

Beyond the nervous system

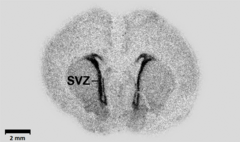

mRNA expression of the embryonic variant of the GABA-producing enzyme GAD67 in a coronal brain section of a one-day-old Wistar rat, with the highest expression in subventricular zone (svz)

Besides the nervous system, GABA is also produced at relatively high levels in the insulin-producing β-cells of the pancreas. The β-cells secrete GABA along with insulin and the GABA binds to GABA receptors on the neighboring islet α-cells and inhibits them from secreting glucagon (which would counteract insulin’s effects).

GABA can promote the replication and survival of β-cells and also promote the conversion of α-cells to β-cells, which may lead to new treatments for diabetes.

GABA has also been detected in other peripheral tissues including

intestines, stomach, Fallopian tubes, uterus, ovaries, testes, kidneys,

urinary bladder, the lungs and liver, albeit at much lower levels than

in neurons or β-cells. GABAergic mechanisms have been demonstrated in

various peripheral tissues and organs, which include the intestines, the

stomach, the pancreas, the Fallopian tubes, the uterus, the ovaries,

the testes, the kidneys, the urinary bladder, the lungs, and the liver.

Immune cells express receptors for GABA and administration of GABA can suppress inflammatory immune responses and promote "regulatory" immune responses, such that GABA administration has been shown to inhibit autoimmune diseases in several animal models.

In 2018, GABA has shown to regulate secretion of a greater number of cytokines. In plasma of T1D patients, levels of 26 cytokines are increased and of those, 16 are inhibited by GABA in the cell assays.

In 2007, an excitatory GABAergic system was described in the airway epithelium. The system is activated by exposure to allergens and may participate in the mechanisms of asthma. GABAergic systems have also been found in the testis and in the eye lens.

GABA occurs in plants.

Structure and conformation

GABA is found mostly as a zwitterion (i.e. with the carboxyl group deprotonated and the amino group protonated). Its conformation

depends on its environment. In the gas phase, a highly folded

conformation is strongly favored due to the electrostatic attraction

between the two functional groups. The stabilization is about 50

kcal/mol, according to quantum chemistry

calculations. In the solid state, an extended conformation is found,

with a trans conformation at the amino end and a gauche conformation at

the carboxyl end. This is due to the packing interactions with the

neighboring molecules. In solution, five different conformations, some

folded and some extended, are found as a result of solvation

effects. The conformational flexibility of GABA is important for its

biological function, as it has been found to bind to different receptors

with different conformations. Many GABA analogues with pharmaceutical

applications have more rigid structures in order to control the binding

better.

History

In 1883, GABA was first synthesized, and it was first known only as a plant and microbe metabolic product.

In 1950, GABA was discovered as an integral part of the mammalian central nervous system.

In 1959, it was shown that at an inhibitory synapse on crayfish

muscle fibers GABA acts like stimulation of the inhibitory nerve. Both

inhibition by nerve stimulation and by applied GABA are blocked by picrotoxin.

Biosynthesis

GABAergic neurons which produce GABA

GABA is primarily synthesized from glutamate via the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) with pyridoxal phosphate (the active form of vitamin B6) as a cofactor. This process converts glutamate (the principal excitatory neurotransmitter) into GABA (the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter).

GABA can also be synthesized from putrescine by diamine oxidase and aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Traditionally it was thought that exogenous GABA did not penetrate the blood–brain barrier, however more current research

indicates that it may be possible, or that exogenous GABA (i.e. in the

form of nutritional supplements) could exert GABAergic effects on the enteric nervous system which in turn stimulate endogenous GABA production. The direct involvement of GABA in the glutamate–glutamine cycle

makes the question of whether GABA can penetrate the blood-brain

barrier somewhat misleading, because both glutamate and glutamine can

freely cross the barrier and convert to GABA within the brain.

Catabolism

GABA transaminase enzyme catalyzes the conversion of 4-aminobutanoic acid (GABA) and 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) into succinic semialdehyde and glutamate. Succinic semialdehyde is then oxidized into succinic acid by succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase and as such enters the citric acid cycle as a usable source of energy.

Pharmacology

Drugs that act as allosteric modulators of GABA receptors (known as GABA analogues or GABAergic drugs), or increase the available amount of GABA, typically have relaxing, anti-anxiety, and anti-convulsive effects. Many of the substances below are known to cause anterograde amnesia and retrograde amnesia.

In general, GABA does not cross the blood–brain barrier, although certain areas of the brain that have no effective blood–brain barrier, such as the periventricular nucleus, can be reached by drugs such as systemically injected GABA. At least one study suggests that orally administered GABA increases the amount of human growth hormone (HGH).

GABA directly injected to the brain has been reported to have both

stimulatory and inhibitory effects on the production of growth hormone,

depending on the physiology of the individual. Certain pro-drugs of GABA (ex. picamilon)

have been developed to permeate the blood–brain barrier, then separate

into GABA and the carrier molecule once inside the brain. Prodrugs allow

for a direct increase of GABA levels throughout all areas of the brain,

in a manner following the distribution pattern of the pro-drug prior to

metabolism.

GABA enhanced the catabolism of serotonin into N-acetylserotonin (the precursor of melatonin) in rats.

It is thus suspected that GABA is involved in the synthesis of

melatonin and thus might exert regulatory effects on sleep and

reproductive functions.

Chemistry

Although in chemical terms, GABA is an amino acid

(as it has both a primary amine and a carboxylic acid functional

group), it is rarely referred to as such in the professional,

scientific, or medical community. By convention the term "amino acid",

when used without a qualifier, refers specifically to an alpha amino acid. GABA is not an alpha amino acid, meaning the amino group is not attached to the alpha carbon so it is not incorporated into proteins.

GABAergic drugs

GABAA receptor ligands are shown in the following table:

| Activity at GABAA | Ligand |

|---|---|

| Orthosteric Agonist | Muscimol, GABA, gaboxadol (THIP), isoguvacine, progabide, piperidine-4-sulfonic acid (partial agonist) |

| Positive allosteric modulators | Barbiturates, benzodiazepines, neuroactive steroids niacin/niacinamide,, nonbenzodiazepiness (i.e. z-drugs, e.g. zolpidem, eszopiclone), etomidate, etaqualone, alcohol (ethanol),, theanine, methaqualone, propofol, stiripentol,, and anaesthetics (including volatile anaesthetics), glutethimide |

| Orthosteric (competive) Antagonist | bicuculline, gabazine, thujone, flumazenil |

| Uncompetitive antagonist (e.g. channel blocker) | picrotoxin, cicutoxin |

| Negative allosteric modulators | neuroactive steroids (Pregnenolone sulfate), furosemide, oenanthotoxin, amentoflavone |

Additionally, carisoprodol is an enhancer GABAA activity. Ro15-4513 is a reducer of GABAA activity.

GABAergic pro-drugs include chloral hydrate, which is metabolised to trichloroethanol, which then acts via the GABAA receptor.

skullcap and valerian are plants containing GABAergic substances. Furthermore, the plant kava contains GABAergic compounds, including kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin and yangonin.

Other GABAergic modulators include:

- GABAB receptor ligands.

- GABA reuptake inhibitors: deramciclane, hyperforin, tiagabine.

- GABA transaminase inhibitors: gabaculine, phenelzine, valproate, vigabatrin, lemon balm (Melissa officinalis).

- GABA analogues: pregabalin, gabapentin, picamilon, progabide

In plants

GABA is also found in plants. It is the most abundant amino acid in the apoplast of tomatoes. Evidence also suggests a role in cell signalling in plants.